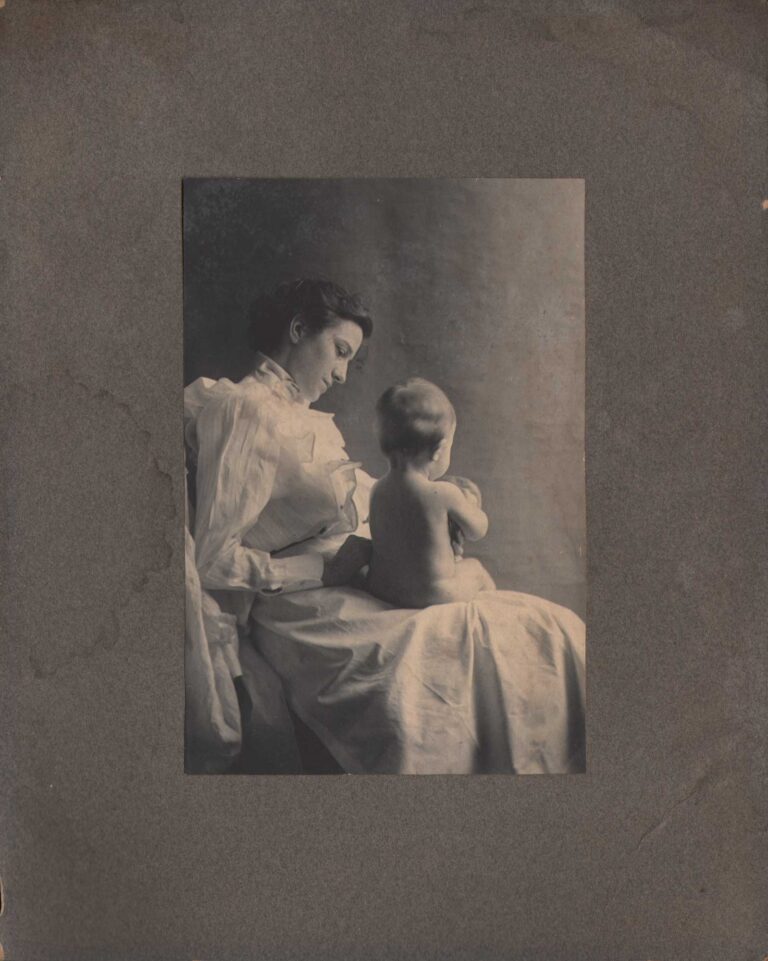

Helen L. Marshall Home Portrait

A specialist in the new field of home portraiture, Photographic Society of Philadelphia member Mathilde Weil (1872-1942) made an early name for herself beginning around 1898 photographing the well-to-do and society families in her native Philadelphia.

This portrait of Helen L. Marshall, one of four on this website from the sitting, is believed to have been taken in early 1899 based on the known birth year of the sitter. Helen Marshall Eliason, (11 July, 1896-1985) a member of Philadelphia society, would go on to live in Jamestown, RI after her husband’s early passing. Among other accomplishments, she would become a successful author and was an active member of the Jamestown Garden Club and Historical Society there.

At the time they were taken, Helen Marshall’s father Dr. John Marshall (b. 1855) was Professor of chemistry and toxicology in the Medical Department at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. Her mother was Mary W. Wormley. Helen would go on to marry Hiram B(rown) Eliason (1892-1921) of Philadelphia on September 10, 1917 at her family’s summer home, “Cedar Point” located atop a rocky outcrop overlooking Mackerel Cove in Jamestown, RI. (since demolished-196 Highland Drive) The young couple would reside at 320 S. 16th St. in Philadelphia.

print notes | provenance: support recto: signed at lower right corner of window impression in graphite: Mathilde Weil Philadelphia; signed lower in an unknown hand in graphite: Helen L. Marshall (Eliason) 2½ yrs

provenance: acquired by PhotoSeed in 2016 from a Newport, RI seller who states it was purchased at an area estate.

MISS MATHILDE WEIL AND HER WORK

Wilson’s Photographic Magazine (USA) in their August, 1902 issue provides an early assessment of Mathilde Weil, who began taking pictures professionally around 1898 and soon became one of the most sought-after and expensive portrait photographers working in the US:

[In a recent issue of the Chicago Record-Herald we find the following interesting account of Miss Mathilde Weil, a Philadelphia professional, whose portrait work has been widely recognized as of the highest quality. After making due allowance for press verbiage we believe that our readers will find profitable suggestions in the account. In publishing it we take the opportunity to congratulate Miss Weil upon her success. We have seen and admired her work, and it deserves success in every way. —editor W. P. M.]

The question of opening new employments to college women is one that many observers consider rather carefully. The profession of teaching is, of course, a definite one, and offers an assured income from the very beginning. Therefore, it is not strange that most girls after receiving their A. B. drift into it. The proportion entering other professions is comparatively small, and business thus far has attracted very few.

Miss Mathilde Weil, consequently, a Bryn Mawr graduate of the class of ‘92, deserves much credit for having shown what a well-educated woman can accomplish in artistic photography. Miss Weil is a Philadelphian, and an exhibition of her most successful work was given not long ago in the rooms of the Philadelphia Camera Club.

The subjects are numerous, but portraits of elderly women and children predominate, and these are usually figure studies, taken in their home surroundings.

A boy on his hobby-horse, a child at his toy piano, two children playing on the beach, a little girl surrounded by her dolls, an elderly woman in a high-backed chair, all these appeal to us as compositions rather than as simple portraits.

In college Miss Weil made no special study of chemistry or physics, or any of the branches that might be supposed to pave the way toward photography. Instead her work lay chiefly along the line of literature and political economy, and she took a year of graduate work in addition to the four years’ course.

After leaving college she was engaged in certain lines of literary work, but her artistic training led her to seek some field for her artistic taste. Her art training included courses in the Philadelphia Museum of Industrial Art and Textile School, with considerable attention to modelling and designing, and she has had other instruction, as, for example, a summer class at Amisquam.

It was not so very strange, then, that when she had spent some time in amateur photography she should begin to look at it with a professional eye.

Her art training had given her an artistic training for her work such as few photographers possess. But her study of political economy had led her to believe that she had no right to enter the labor market in competition with any but the highest bidders. Certainly no woman, and probably no man, outranks her in price—$25 for the first appointment, and $2.50 for each appointment after the first.

Of course, before Miss Weil started out as a professional she had practised more or less on friends. With her high standard this was, of course, an expensive amusement, and she found that those who desired her skill were willing to pay well for it.

Miss Weil is now a professional photographer, with her studio in the heart of Philadelphia. But she is constantly asked to go to outlying country places, as well as to Baltimore and New York. Her success seems to justify the principle on which she started, that photography is no more mechanical than painting.

The lenses, the plates, are the instruments, but the photographer who is an artist, like the painter, can impress his individuality on his work. On this account Miss Weil makes a very complete study of her subject. The photograph should be of real value as a picture, something that even people outside the family will like. Its artistic strength should lie largely in the matter of lights and shades. The tonal values and the relations of the masses are the things chiefly to be considered, and the result is that the present exhibition gives the impression of a series of fine photographs from fine paintings rather than from life.

The reason for the naturalness of Miss Weil’s work is her shunning of the skylight. Whenever she can do so she photographs her subjects in their own homes, and when they come to her studio they still find no skylight.

In the matter of subjects she has no choice, although the elderly and the youngest people are usually the least conscious in their poses, and thus the most satisfactory.

Although Miss Weil has been in business only four years, she won, two or three years ago, the Royal Photographic Society’s medal offered in London, which a few years previously had been won by Miss Emma Fitz, of Boston. Although this in the eyes of the photographic world is the most important of Miss Weil’s prizes, she attaches as little importance to it as to the many others, national and international, that she has won. She cares more to satisfy herself and gain the approval of discriminating critics than to win prizes.

This, to be sure, is coming to be the opinion of most artistic photographers. They prefer to be invited to send their pictures to an exhibition where the standard is high rather than to be permitted to send them to one where the test of merit seems to be the winning of prizes.

Miss Weil’s studio is a fascinating apartment, with none of the paraphernalia for photography in sight. On the walls of the reception-room hang a few of her photographs in artistic frames. There are also occasional water colors and other well-chosen pictures, both in this room and the room with the north light. Although this latter room might by courtesy be called the operating-room, it looks simply like the sitting-room of some private house.

The rugs in both rooms are well chosen, the furniture is antique and simple in outline. A shelf running around the room some inches from the ceiling hold numerous articles of bric-a-brac—busts, statuettes, vases.

On one wall is a collection of old French fans, on another a number of odd posters. An inlaid desk is in one corner, and there are many other objects around the room.

On the top floor Miss Weil has her printing and finishing-room. All her printing and finishing Miss Weil does herself, with the help of only one assistant, and her own careful attention to detail accounts in large part for her artistic success.

Artistic photography pursued in the conscientious spirit in which Miss Weil pursues it certainly opens a fine field to the trained college graduate who wishes to work along lines that are not yet overcrowded. (pp. 313-14)