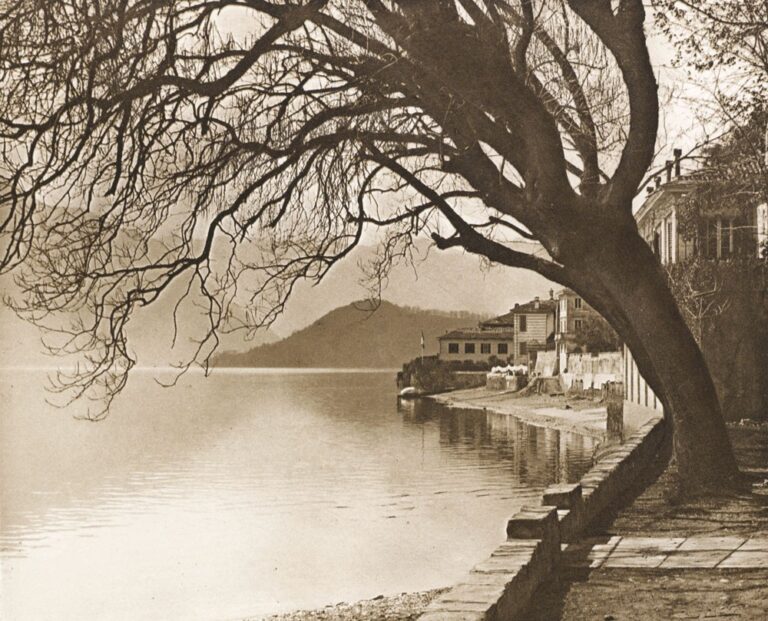

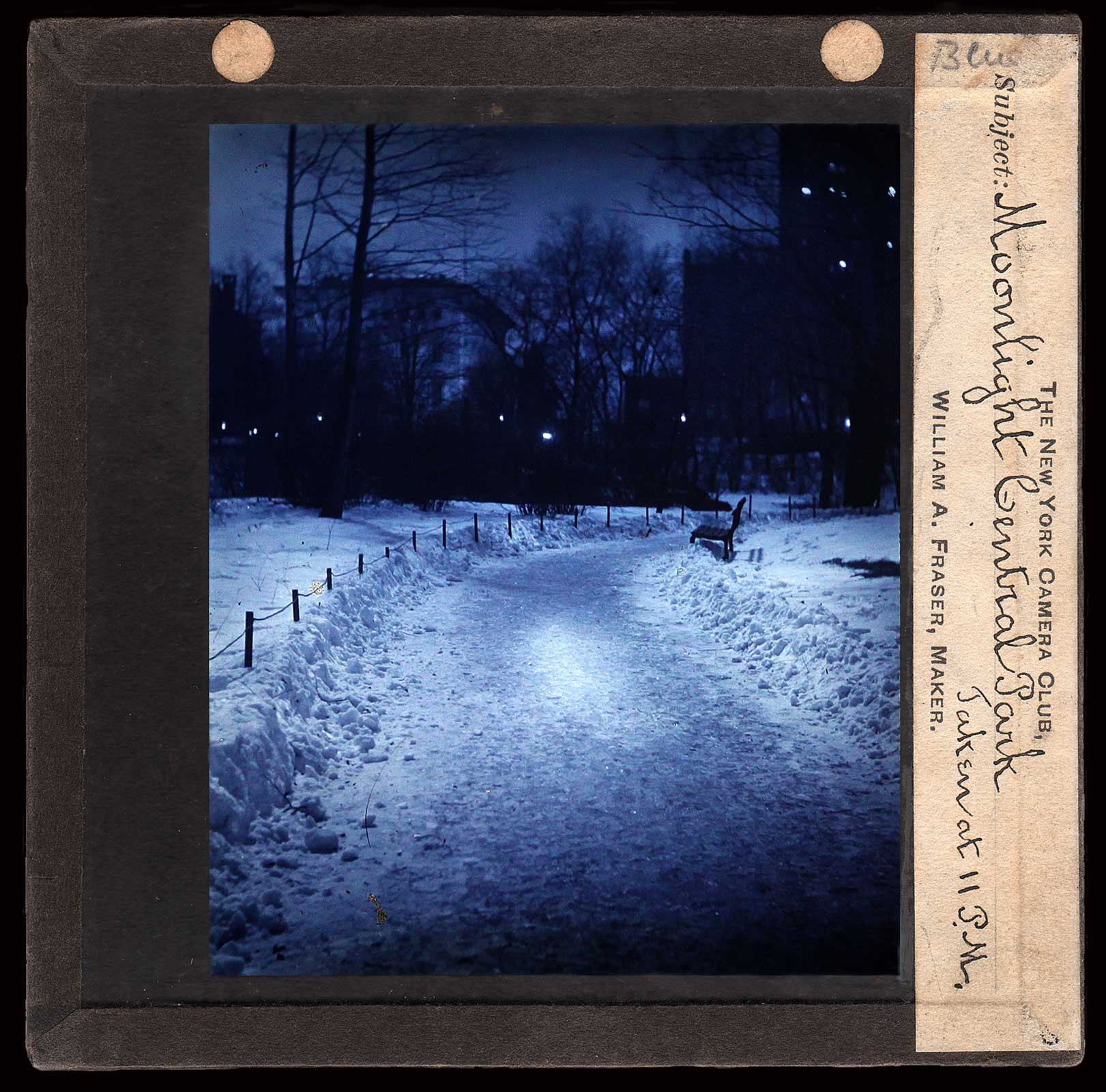

Moonlight, Central Park

Taken in New York City by William Fraser in late 1896 or very early 1897, this blue-tinted lantern slide is a rare surviving example of the pioneering work in early night photography by Fraser. Purchased by this archive in 2017 from an English antiques dealer, it intriguingly may also have been the original slide exhibited as part of the Royal Photographic Society’s 42nd annual exhibition held in London in late September, 1897.

Moonlight, Central Park was published in The Photographic Times as part of a series of halftone photographs by this amateur photographer illustrating his article Night Photography which appeared in the April, 1897 edition:

Night Photography.

By W.A. Fraser.

Having been asked by your editor to describe my method of working in night photography, I would first say that with perhaps the exception of the combination of snow with moonlight and electric lights, and even this may have been done before, I make no claim to originality, my first attempts having been made after reading the articles on the subject, published in the London Amateur Photographer by Mr. Paul Martin.

Thanks to these articles, I was enabled to start from the point where Mr. Martin had ceased experiment and reached success, and beyond a supply of energy, and sufficient enthusiasm to disregard storm and cold, I find very little else is needed.

The first requisite is a strong weather-proof box camera. The one I use for this work is an old style Scovill detective, long ago laid on the shelf, but it struck me when thinking the matter over, that its strength and solidity, made it a very suitable instrument for this purpose, and much work done with it during the past winter has confirmed me in this opinion.

I carry a light folding tripod which can be quickly and easily attached to or detached from the camera, as working in the dark with hands numb from cold and wet, the simplest operation becomes a task, and the more simple the apparatus, the better the chance of success.

The lens I use is a Ross rapid symmetrical worked at full opening f8. Mr. Martin advises the use of a slow orthochromatic plate, but considering the good quality of the fast plates as now made, and the great advantage gained by reducing the time of exposure, an advantage which one will appreciate after a single trial, I very much prefer them, and results do not, in my opinion, suffer in the least from their use.

As halation must be guarded against, I adopted for this work the Seed non-halation plate, and back them as a further precaution. Working on Mr. Martin’s lines I at first included in the exposure a minute or two of the last departing daylight, if it might so be called, but my negatives approached too nearly daylight results, and I have since waited until night has really fallen before making the exposure.

Having chosen the view and set up the camera, if the only lights included are gas lamps, the exposure with this lens and plate should be from eight to ten minutes, depending somewhat upon the distance to the nearest light, while, if any near electric lights are included, from two and one-half to three and one-half minutes will suffice.

When I speak of electric lights, I refer to those enclosed in opal shades, such as are used on Fifth and upper Madison Avenue in our city. Unprotected lights or those enclosed in plain glass shades I have never attempted, and doubt very much if they can be successfully photographed.

My moonlight pictures were taken between 10 and 11 o’clock, P.M., with moon almost full, and ten minutes’ exposure.

During the exposure, a watch must be kept that no vehicle carrying lights crosses the field of view. My practice is to stand beside the camera, keeping one hand firmly on it, if it is blowing hard, several exposures I found were ruined through movement of the camera caused by the strong wind, then when a cab or other vehicle carrying a light enters the field of view, I, with the other hand, cover the lens until it has passed.

Moving objects not bearing lights makes no impression on the plate. In the development I aim at softness, and use a rather weak metol developer, two ounces stock solution diluted with water to four ounces, and with very little, say two drachms alkali, no bromide.

The amount of detail picked up by the lens when using this plate, has been a constant source of wonder to me; in every case, very much more than my eye could see, was disclosed when the plate had been developed and fixed.

I prefer a stormy night for this work, either snow or rain, as the artistic effect is unquestionably much greater on these occasions.

Before starting out one’s mind must be made up to bear with equanimity all sorts of chaff and uncomplimentary remarks, which are sure to be showered upon the photographer by the majority of the passers by. I have received a great deal of advice and sympathy concerning my mental make-up and condition, and if Robert Burns were still living, I should suggest to him that a trial of night photography might partially, at least, fulfil his wish as expressed in the lines

“O would some power the giftie gie us

“To see oursels as ithers see us.”

This is varied by a multitude of inquiries ranging from the sublime to the ridiculous, and also indication that an interest in science is abroad on the streets of New York, as I have more than once heard John explaining to Mary as they passed that I was taking a picture by those X-rays the papers have been talking about.

One very stormy night towards the end of November, when making one of my earliest attempts, I was standing by my camera vainly (as it turned out) trying to get a bit which had pleased me, when I heard a voice outside my umbrella saying, ” Say, mister, take my picture.” On turning round I found it was my good friend, W. B. Post. Even he had not been able to resist the inclination to chaff a fellow-worker when he found him in what seemed a ridiculous position.

In conclusion, I firmly believe there are great possibilities for pictorial effect in this night photography, and to the enthusiastic amateur, whose daylight leisure hours are limited, a very broad field of work is opened up. I confidently expect to see great improvement, and some startling effects produced, when it has been taken up and studied by a greater number of workers.

NOTE.

In order to encourage our readers in this branch of photography, we offer a silver and a bronze medal for the best photographs made at night. This competition will close on the 30th April next. (pp. 161-63)

Further reproduced: article and photographs including Moonlight, Central Park: in: Sunlight and Shadow | A Book for Photographers Amateur and Professional; edited by W.I. Lincoln Adams, New York: The Baker & Taylor Company, 1897: pp. 113-17

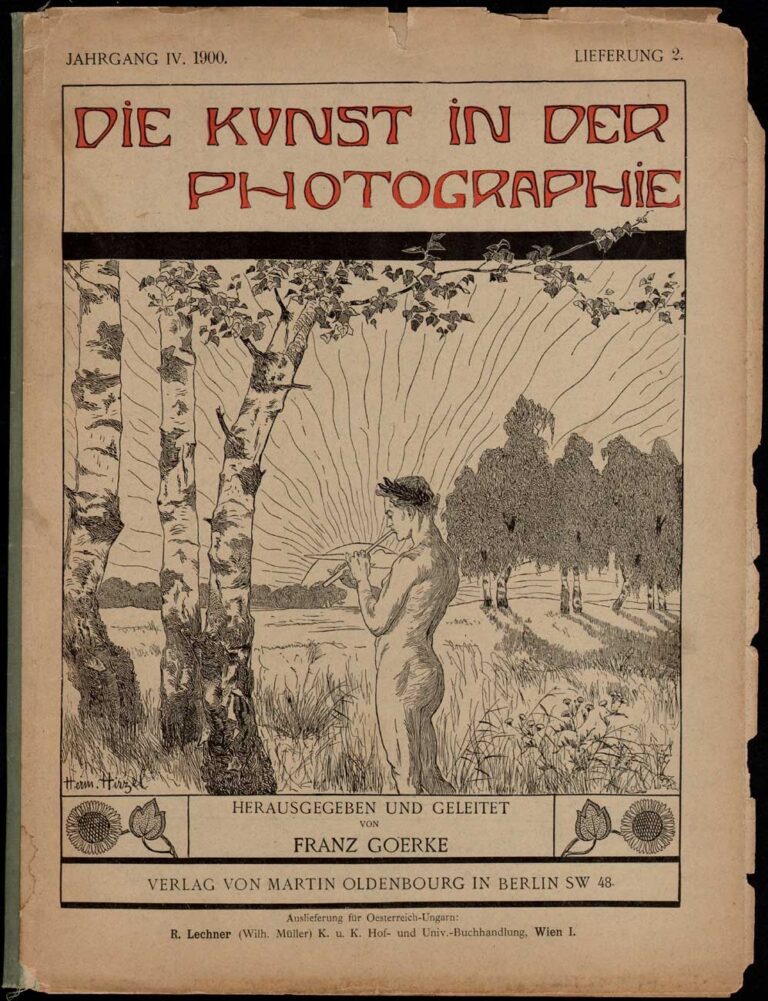

Further reading: “Photographing at Night” in The Photo Miniature: New York, Tennant and Ward, October, 1901: pp 302-03

Slide notes: Engraved paper label for The New York Camera Club, William A. Fraser, Maker. can be seen pasted on right hand side of slide recto. Notations: at top of slide in graphite: Blue; Subject: Moonlight Central Park Taken at 11 P.M. in black ink.

Provenance: Purchased for this archive in March, 2017 from an antiques dealer in Worcestershire, United Kingdom. As stated in the introduction of this entry, the slide may be one of the original twelve that William Fraser exhibited as part of the group: Twelve Lantern Slides – Around New York, after Dark included in the Forty-second Annual Exhibition of the Royal Photographic Society which took place in London, England from September 27- November 13, 1897.