Title Page: On English Lagoons: Being An Account of the Voyage of Two Amateur Wherrymen on the Norfolk & Suffolk Rivers & Broads

Title page for volume

On English Lagoons

Being An Account of the Voyage of Two Amateur Wherrymen

On the Norfolk & Suffolk Rivers & Broads

By

P. H. EMERSON

With an Appendix

The Log of the Wherry “Maid of the Mist”

From September 15, 1890, to August 31, 1891

Illustrated by Fifteen Copperplate Engravings and Eighteen Views

from Photographs taken by the Author

London

DAVID NUTT, 270-71 STRAND

1893

{All rights reserved}

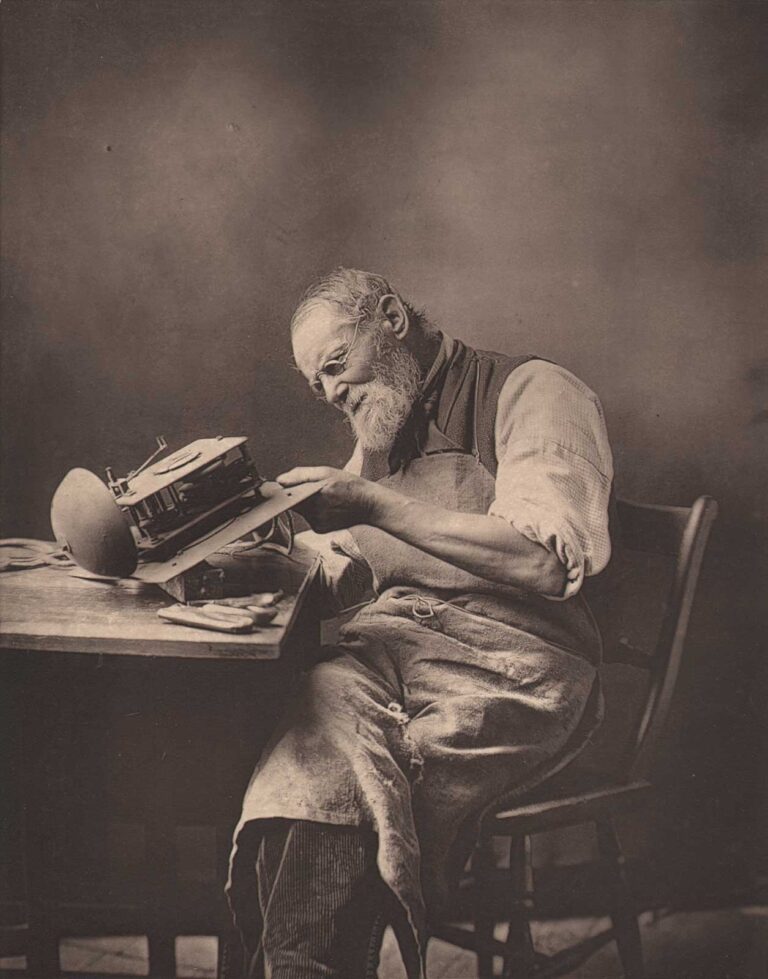

On English Lagoons is considered Peter Henry Emerson’s rarest work, with only 50 copies of the deluxe limited edition of 100 believed to have been printed. Notable for its 15 finely executed copper-plate hand-pulled photogravure plates from the original photographic negatives depicting Broadland scenes, Emerson (1856-1936) had earlier mastered the gravure process after learning it in the late 1880’s. His teacher was Walter L. Colls, (1856-1936) English copperplate engraver, amateur photographer and Linked Ring Brotherhood member. Lagoons was the culmination of Coll’s teaching, as Emerson would go on to personally etch all the copper plates and print the gravures for the deluxe copies. (an unlimited edition with no gravure plates was also published at the same time) The photographer would go on to issue only one other volume with his photographs made from photogravure plates- his masterwork Marsh Leaves, which can also be seen on this website that was published by David Nutt in London in 1895.

This is copy #30 signed by the publisher David Nutt of the limited, deluxe edition. Emerson made it a goal of placing his published work in institutions, primarily libraries, but also in the collections of camera clubs throughout England. This is one such copy with a collection stamp placed on the corner or within the plate of all the gravures- a standard practice by these institutions in order to prevent the removal of the valuable illustrations. (see provenance below) This copy contains the stamps of County Borough of Grimsby Public Library, located in North East Lincolnshire.

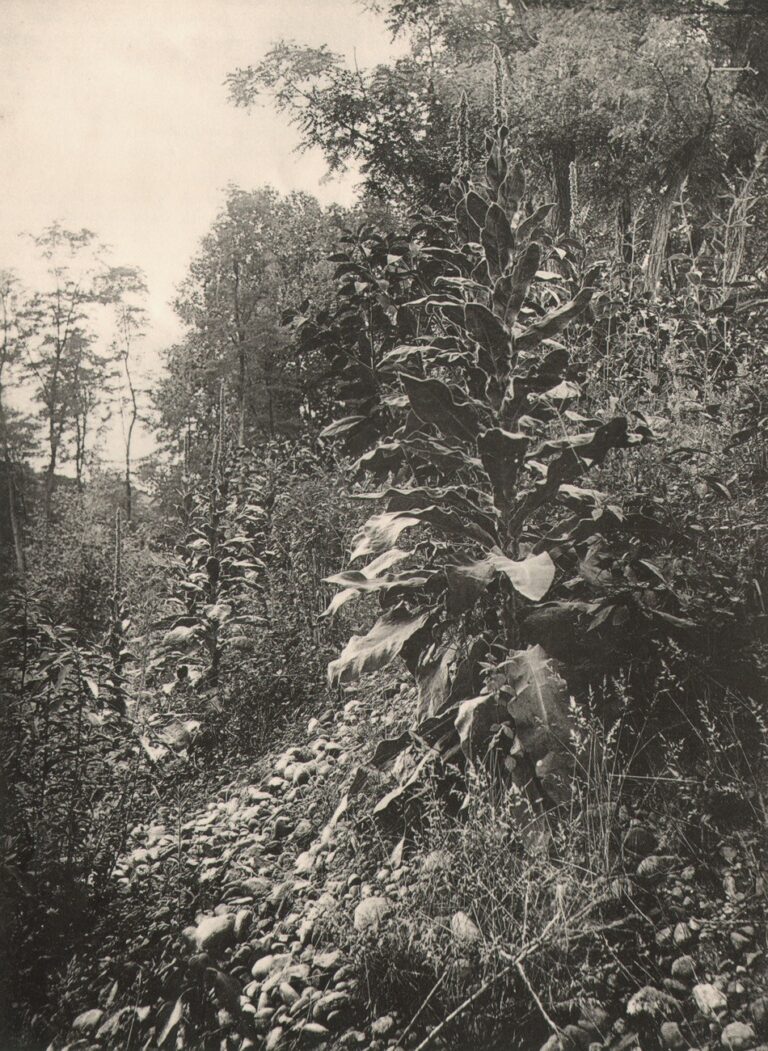

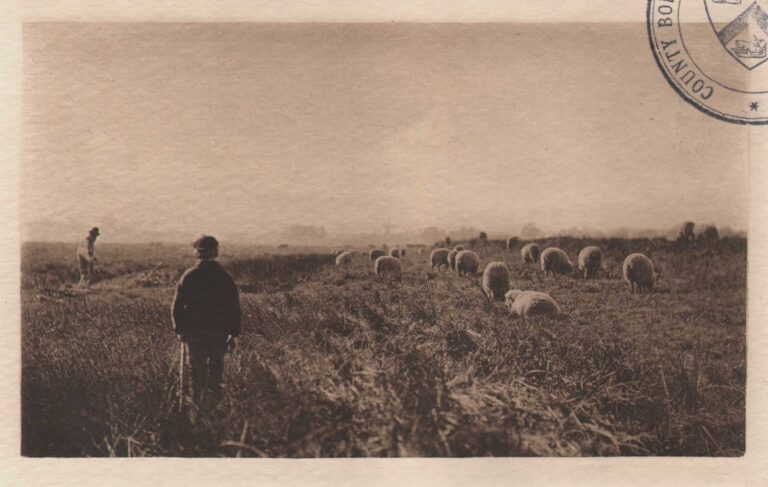

Essentially a travelogue of his observations taken on a journey over the course of a year on the Norfolk Broads, we care more today about Emerson’s vision as translated in his photographs for the deluxe edition, rather than the text of the volume. This reality would have been the opposite of how a reader might have reacted had they chosen to read the book in 1893 for purposes of gleaning background on the region:

“On English Lagoons’ fifteen gravures are largely subordinate to the lengthy narrative text chronicling his year aboard a wherry, cruising East Anglian waters (1890-1891). The delicate, distant landscape vignettes that predominate here presage the chilly finality of those in Marsh Leaves. So too does their breathless quality of suspension of time and action, as in At the Ferry—A Misty Morning.” (1.)

A Contemporary Take on English Lagoons

An in-depth review of Lagoons by someone named “I.S.” appeared in the magazine: Nature, A Weekly Illustrated Journal of Science on September 28, 1893. It would appear although Emerson wore several hats, including being called a naturalist, he may have been no expert, with some of his ornithological observations called into question:

YET another book about the Norfolk Broads, or, as the author prefers to call them, the “English Lagoons.” One can hardly credit that anything fresh could be said on this well-worn subject, but Mr. Emerson’s book differs from all that have gone before in being a continuous narrative of a twelve months’ sojourn on the Broads in his pleasure wherry, the Maid of the Mist, and presents to us a graphic picture of these waters under their winter aspect as well as under a summer sky. Much that he has written, more particularly his excellent descriptions of the peculiar scenery of this remarkable admixture of land and water in mid-winter, is highly interesting. The atmospheric effects under various conditions of storm and sunshine, by moonlight and at early dawn, display a keen artistic perception, but the incidents as a rule are trivial in the extreme in fact, and the constant use of the vernacular becomes tiring-whole chapters (e.g. Chapter xxi. of six pages) might have been well omitted.

From a naturalist’s point of view the reader cannot fail to be pleased with the kindly spirit which pervades the book, the evident delight which the author took in his feathered friends, and his disgust for the wanton destruction which is too frequently committed by thoughtless visitors to these delightful retreats, but having said this we confess we are rather puzzled by Mr. Emerson’s ornithology. On page 216, for instance, he mentions watching a pair of desert wheatears on Palling Sand Hills; surely he cannot have met with Saxicola deserti in Norfolk. Scarcely less astonishing is the mention of a blue-headed wagtail’s nest, and the appearance of the white wagtail on several occasions. The present writer has known the Broads for forty years, but has never had the good fortune to meet with Motacilla flava or M.alba, both of which are excessively rare in Norfolk, and probably only occasionally appear as passing spring migrants. Many of the observations on birds are interesting, but the following passage is hardly in good taste. Speaking of Surlingham Broad, “which the late Mr. Stevenson, the local naturalist, loved,” Mr. Emerson continues, “But this piece of water is to me dull and songless, but then Mr. Stevenson did not know shadows from reflections, nor, I suspect, beauties from commonplaces. As a naturalist, moreover, he was not to be compared to the late Mr. Booth, a true lover of birds and of outdoor life. But in Norfolk every native goose is a swan.” Mr. Stevenson’s reputation as an ornithologist is too well established to need any defence from my pen, but I can say without hesitation that the best general description of the Broad district ever written is to be found in the introduction to his “Birds of Norfolk,” and his chapters descriptive of a summer’s night and a summer’s day on the very Broad which Mr. Emerson considers so uninteresting, show not only only his wonderful powers of observation but his keen perception of the beauty and poetry of nature; even so familiar a bird as the redbreast is invested with fresh interest after reading his charming chapter on this pert little friend of man. I. S.

- Foster, Sheila J, Manfred Heiting, and Rachel Stuhlman. Imagining Paradise: The Richard and Ronay Menschel Library at George Eastman House, Rochester. Göttingen: Steidl, 2007 p. 192 (courtesy photogravure.com)