Last August I had the uncommon opportunity to purchase five photographs ca. 1905-1910 that were still in their original picture frames taken by William T. Knox, (1863-1927) then president of the Brooklyn Camera Club.

Detail: “Pleasure Under Summer Skies”: William T. Knox, American: (1863-1927) Vintage sepia Platinum print ca. 1905-10; 19.6 x 24.5 | 19.6 x 24.5 cm (flush-mounted on Bristol-board type matrix). Photograph framed in quarter-sawn oak frame with brass title nameplate made by James Engle Underhill, American: (1870-1914) two-piece integrated: 34.5 x 39.5 x 2.0 cm shown with glass removed. “Pleasure Under Summer Skies” dates to 1905, and was initially exhibited in the Second American Photographic Salon, overseen by the American Federation of Photographic Societies under President Curtis Bell. At the time, William Knox was Federation Secretary. From: PhotoSeed Archive

Additionally, three of them were in beautiful wood frames made by his fellow club member James E. Underhill, 1870-1914, who I discovered had made his living as a fine picture framer since around 1900 in New York City at his shop at 33 John Street, at the corner of Nassau Street.

Before limited conservation, the original James E. Underhill white-paper letterpress label in olive-green (2.9 x 2.0 | 4.3 x 3.2 cm) is seen affixed to the frame backing verso of his oak frame enclosing the William T. Knox photograph “Pleasure Under Summer Skies”. Conservation treatment by this archive carefully left this label in place. James Engle Underhill was a fellow member along with Knox at the Brooklyn Camera Club when this photograph was taken and framed. (ca. 1905-10) Underhill’s picture framing shop: “Jas.E.Underhill, 33 John St., New York City. MAKER PictureFrames.” was in operation at this location (corner Nassau) from around 1900 to his death in 1914. From: PhotoSeed Archive

In my 20+ years of collecting photography, and with a definite impression the “bloom is off the rose” when it comes to the intersection of internet commerce, it seems to me today more difficult to acquire vintage photographs of artistic note still in their original frames. This is a pity, because framed photographs left undisturbed from 100+ years ago can often reveal the more honest intent photographers wished for their work to be seen and appreciated- for the time they were created no doubt, but also on a higher aesthetic level.

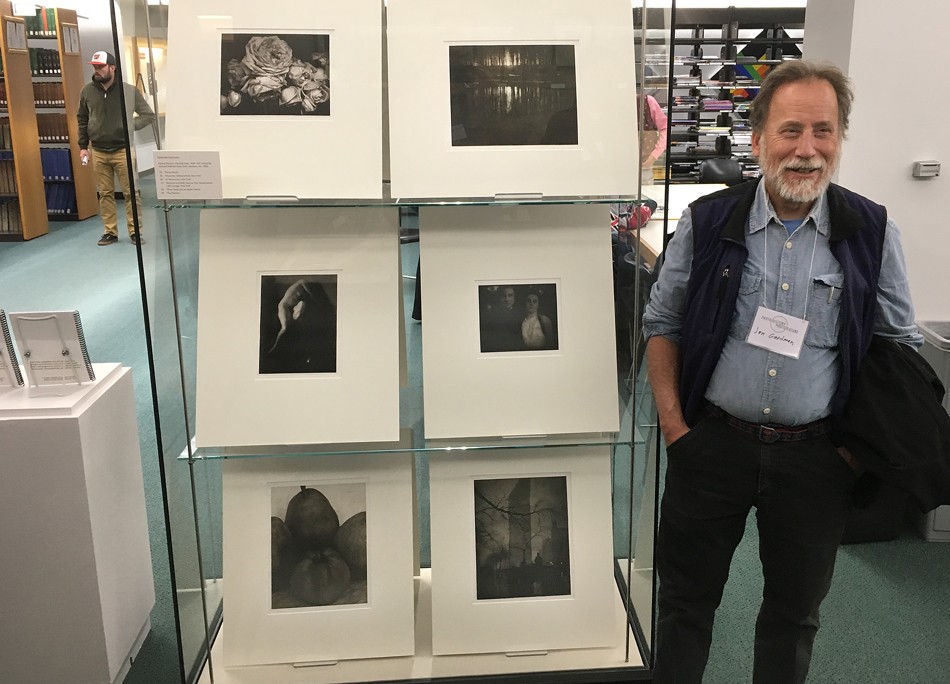

Upper left: When first received by PhotoSeed after purchase in late August, 2019, the verso of the framed William T. Knox photograph “Pleasure Under Summer Skies” is seen in its’ original James E. Underhill oak frame. As was common in framed works from the late 19th and early 20th centuries, a thin sheet of pine wood veneer was used as a backing board, secured by small nails. Upper Right: Conservation treatment on the framed work included removal of this wood backing board along with rusted screw-eyes and wiring used for hanging as well as some of the frame backing paper. The original Underhill framing label is carefully left undisturbed at lower right and the Bristol-board type matrix with flush-mounted photograph on recto is revealed, showing the “burning in” of several wood knot holes from the recto of the original sheet of wood veneer. Next steps included the thorough cleaning of the original framing glass and then cutting a piece of acid-free, 4-ply mat board that would be sandwiched between the photographic matrix and new piece of cardboard backing board. Finally, a Fletcher brand framing gun was used to secure glass, mounted photograph and the two separate backing matrixes using new metal framer’s points to the inside perimeter of the frame verso. Lower Left: Tools at right including small pliers and a wire-cutter were used to remove the original verso framing nails from the William T. Knox photograph “Playmates”, along with an X-Acto knife at far right to cut away the delicate and very acidic backing paper. A unique paper label signed and titled by the artist in the middle of the paper was then carefully removed and preserved within a newly encapsulated frame using a piece of acid-free mat board. New flush-mounted hanging hardware (screw-eyes not recommended!) and braided wire were also installed. Lower Right: A selection shows vintage frames with photographs from the PhotoSeed Archive, including the William T. Knox photograph “Pleasure Under Summer Skies”, now re-installed within its’ original James E. Underhill frame at upper right. To the left of it is a separate frame made by Underhill’s contemporary, George F. Of Jr. (1876-1954) From: PhotoSeed Archive

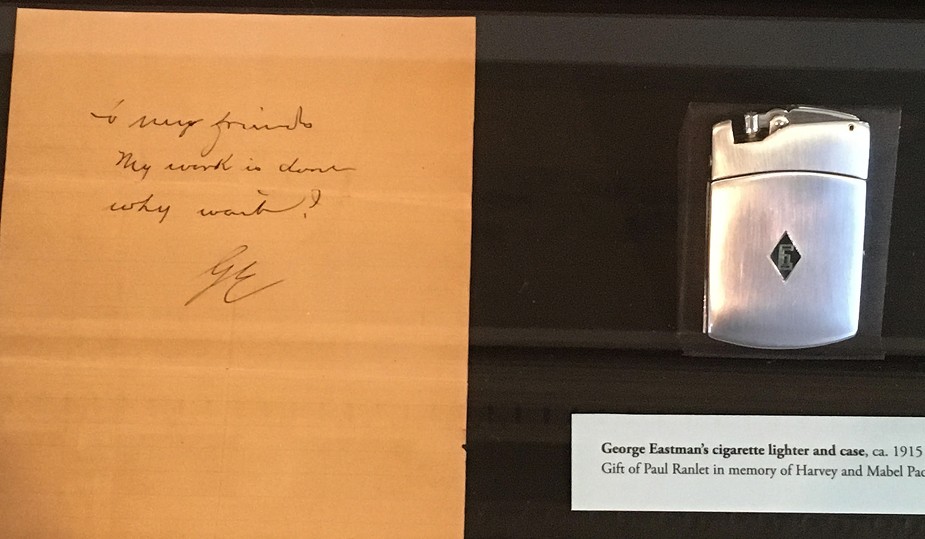

On a technical note, PhotoSeed does minimum conservation on framed works when they enter the collection. The mantra of “do no harm” as well as the realization of being temporary custodians of an archive is embraced. When in doubt about proceeding with photographic conservation, advice given me many years ago from a George Eastman Museum conservator to basically just leave things alone when unsure of how to proceed is something I’ve always kept in mind. Of course, the financial realities of proper conservation standards will always be at the forefront for collectors, both private and institutional.

“Playmates”: William T. Knox, American: (1863-1927) Vintage sepia Platinum print ca. 1905-10; image: 12.0 x 23.5 mounted on fine art papers: 19.6 x 24.5 | 19.6 x 24.5 cm. This fine children’s genre study by Brooklyn Camera Club president William T. Knox dates to 1905 or slightly before as it was known to have been exhibited in the Second American Photographic Salon that year. It shows a young child attaching a leash from his faithful canine companion to his toy wooden wheelbarrow. From: PhotoSeed Archive

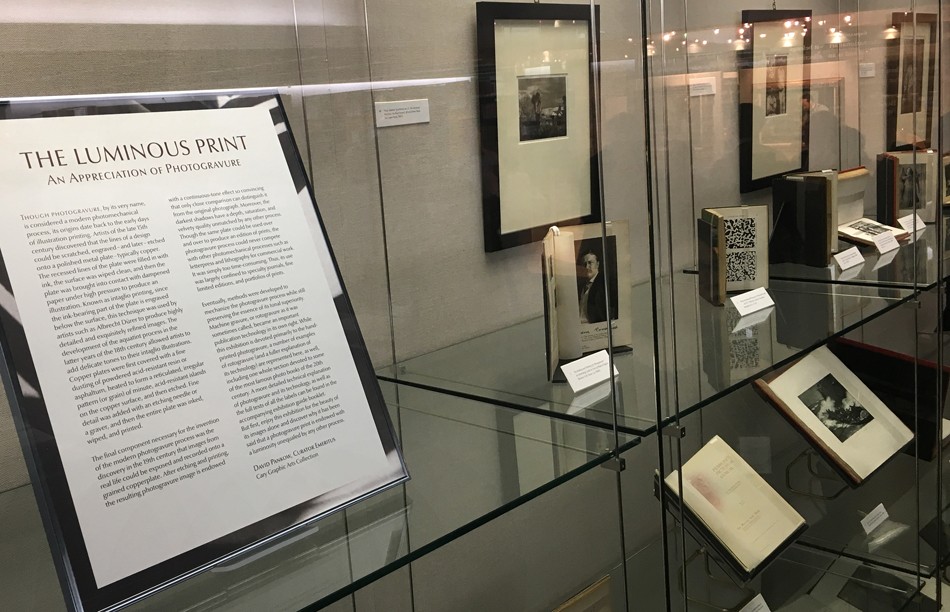

Frame Conservation: A Few Ideas

For framed works, conservation on my end typically includes the removal of acidic frame backing materials and replacement with acid-free mounting materials that come into direct contact with the physical print. Embedded dirt and other foreign matter is then carefully removed and or wiped away from the frame itself, with original finishes showing the passing of decades left deliberately intact and never stripped off. Finally, everything is put back together for storage or display: the original glass from the frame is also cleaned on both sides and then carefully put back into place. If cracks are discovered or worse, replacement with a custom cut piece of window glass will typically suffice.

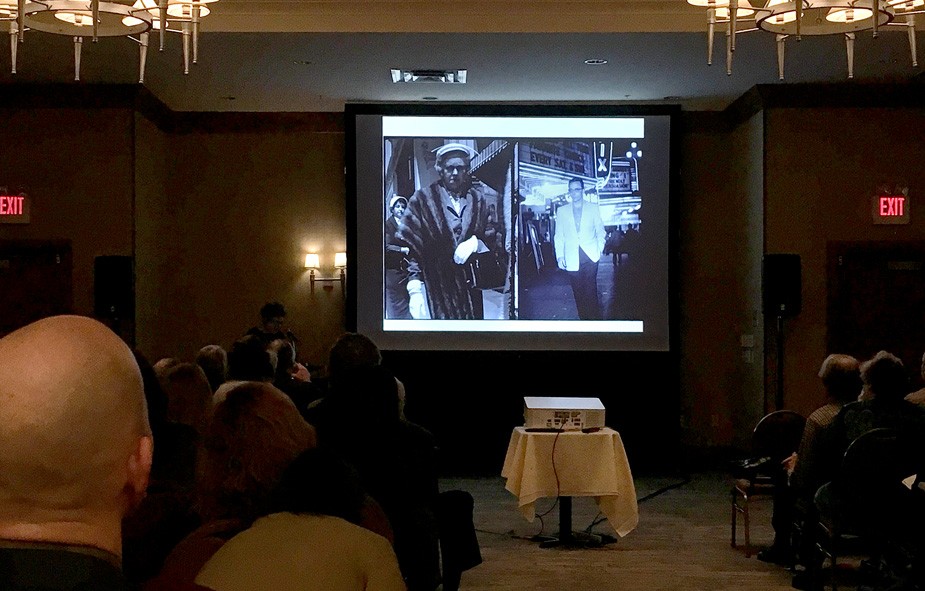

Digital Presentation on PhotoSeed

For digital presentation on this website, the frame is then photographed separately and the print scanned. I use Photoshop to combine the two-leaving the original framing glass out. Purists may object to this but I’m not changing the physical object in any way-just taking advantage to present you with an optimum web experience. Of course, the joy of collecting is being able to appreciate a vintage photograph in the very best form possible: in person. Never the less, I’ve included a small photo along with three other conservation snaps in this post showing a small display of conserved and “reframed” works from this archive. Other examples can be found here.

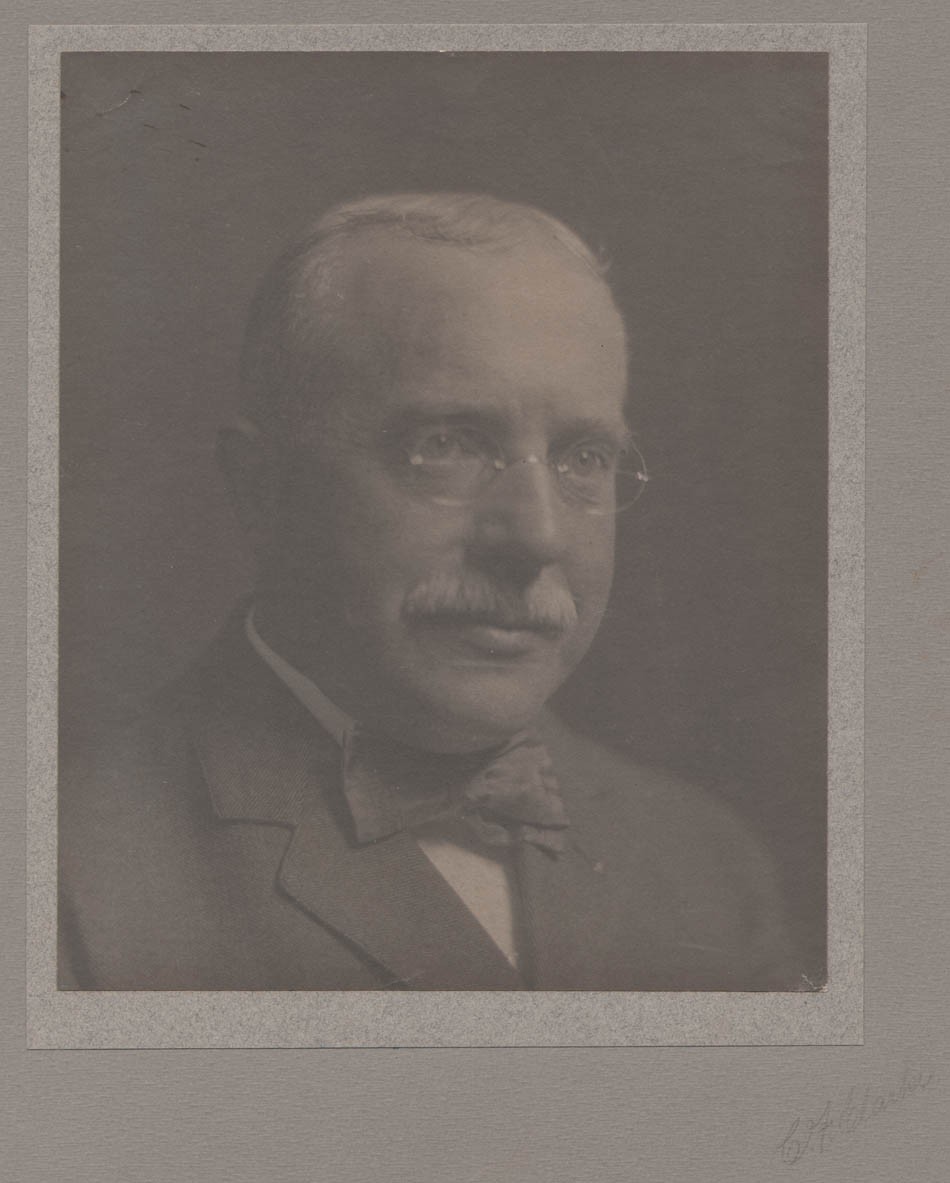

“Portrait: Brooklyn Camera Club President William T. Knox”: Charles Frederick Clarke, American, born Nova Scotia: (1865-1912) image: 21.7 x 17.8 cm; supports: light-gray art paper 23.7 x 19.4 | 36.4 x 29.5 cm; Vintage platinum print ca. 1905-10. William T. Knox (1863-1927) was an important American amateur photographer and promoter of photography from Brooklyn, New York. From at least 1891-1915, he was a partner of McCormick, Hubbs & Co., importers and commission merchants in West India and Florida Fruits and Produce with offices at 279 Washington Street in New York City. (Manhattan) From: PhotoSeed Archive

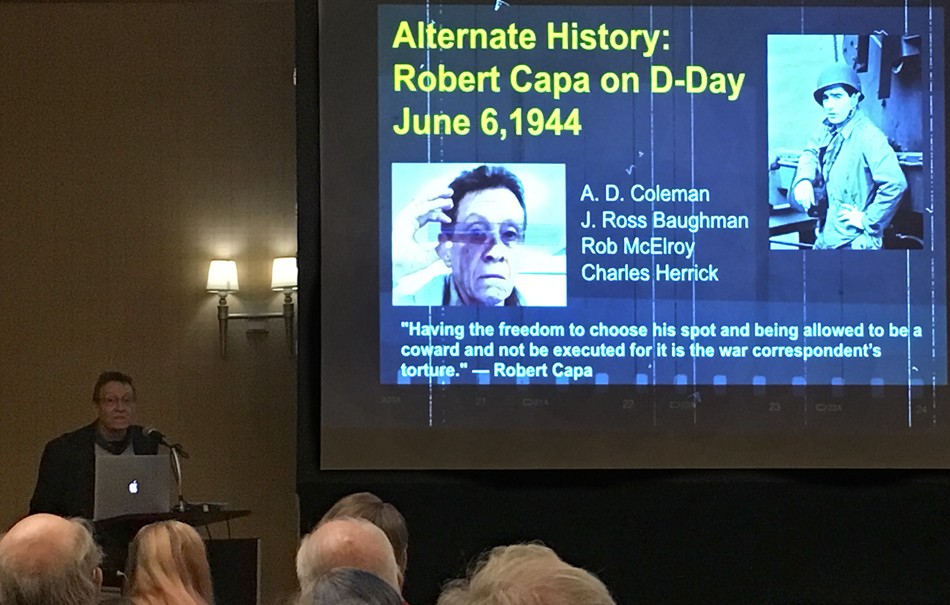

Intriguingly, I have owned a platinum portrait of William T. Knox, showing him to be quite the dapper gentleman- mustachioed, and sporting a bow tie taken about the same time he was club president, for many years prior to my collecting any of his actual photographs. This was by Charles F. Clarke, 1865-1912, (American, born Nova Scotia) an amateur and business agent for the Forbes Lithograph Company of Springfield, MA.

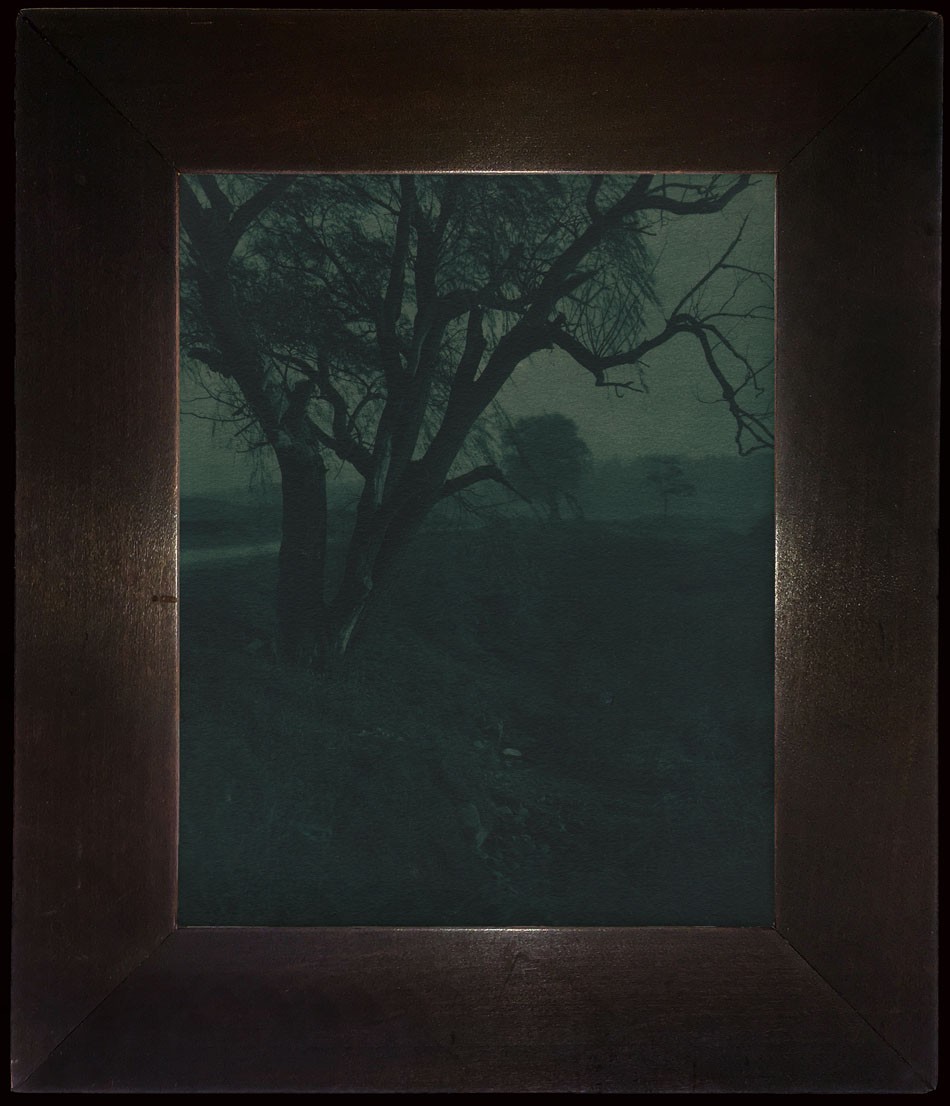

“Landscape in Green Carbon”: attributed to William T. Knox, American: (1863-1927) Vintage green Carbon print ca. 1905-10; image: 23.4 x 19.7 cm flush mounted to thick, Bristol-board type matrix: 23.6 x 19.7 cm shown within its’ original oak frame: 32.6 x 28.6 x 2.0 cm (with glass removed) by James E. Underhill (1870-1914) of New York City. Knox and Underhill were members of the Brooklyn Camera Club when this photograph was taken and framed. From: PhotoSeed Archive

You can see all of Mr. Knox’s framed works in the collection here, which includes a professional chronology for his friend the framer and fellow Brooklyn Camera Club member James E. Underhill. Happy hunting! -David Spencer