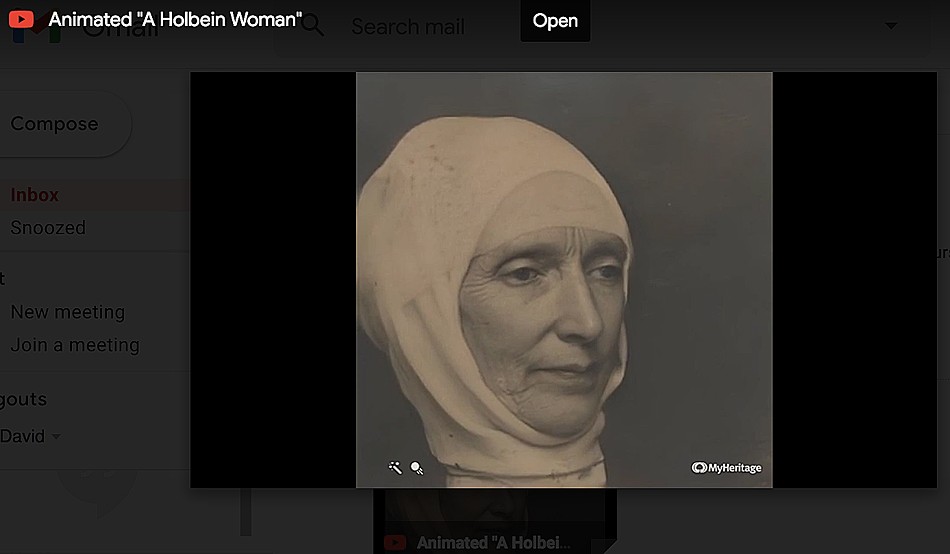

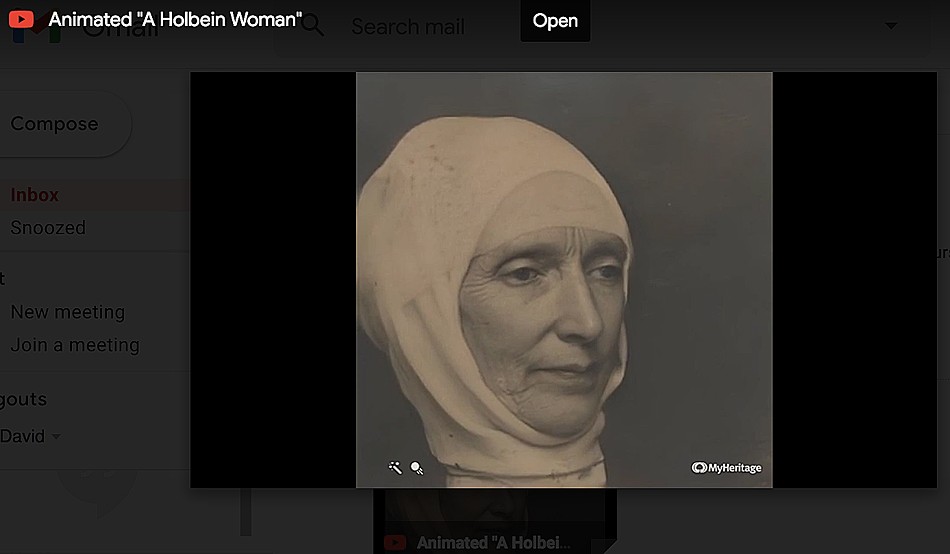

A reappraisal of old photos has recently invaded the public conversation of late. Artificial intelligence, in the form of video driver technology invented by Israeli company D-ID, was licensed earlier this year to genealogy and DNA company MyHeritage with the moniker Deep Nostalgia™. Old photographs, no matter their original medium, are brought to life as short animated video clips, and may never be seen in the same way again.

Screenshot: Animated “A Holbein Woman” from YouTube. Cropped image of same by American photographers Frances Stebbins & Mary Electa Allen, ca. 1890 using the Deep Nostalgia™ app licensed to genealogy and DNA company MyHeritage. Original source photograph from PhotoSeed Archive.

Taking up the company’s free offer to try out the technology, I applied it to a recent archive acquisition, A Holbein Woman, taken in the very early 1890’s by Deerfield, Massachusetts sister photographers Frances Stebbins and Mary Electa Allen. You can see the result in a short 12 second video posted to YouTube embedded above in this post.

Left: Colorized version of “A Holbein Woman” by American photographers Frances & Mary Electa Allen, ca. 1890. Created by DeOldify deep learning experts Jason Antic and Dana Kelley, this colorizing technology has been licensed from DeOldify by DNA company MyHeritage, with their branding of MyHeritage In Color™. Source photograph from PhotoSeed Archive. Right: “Portrait of a Woman from Southern Germany”: c. 1520-25: Formerly attributed to Hans Holbein the Younger, Germany: (1497/1498-1543): Oil on panel: 45 x 34 cm: Courtesy: collection of the Mauritshuis museum in The Hague.

The photograph, considered a masterwork of early genre pictorialist portrait photography, is of their mother Mary Stebbins Allen, (1819-1903) and in itself done after the then fashionable practice (1.) of an imitation painting: in this case, a Renaissance portrait by Bavarian artist Hans Holbein the Elder. (c. 1460-1524) To add another layer of mystery, research I did last year revealed the primary source portrait- the oil painting (c.1520-1525) known as “Portrait of a Woman from Southern Germany” in the collection of the Mauritshuis museum in The Hague, was originally attributed to Holbein’s son “The Younger”, (c. 1497-1543) with the now updated disclaimer by the museum’s curators as being “formerly attributed” to this artist. This painting can be seen at upper right, with a colorized version of the Allen sisters portrait run through remarkable colorization technology MyHeritage In Color™ at left.

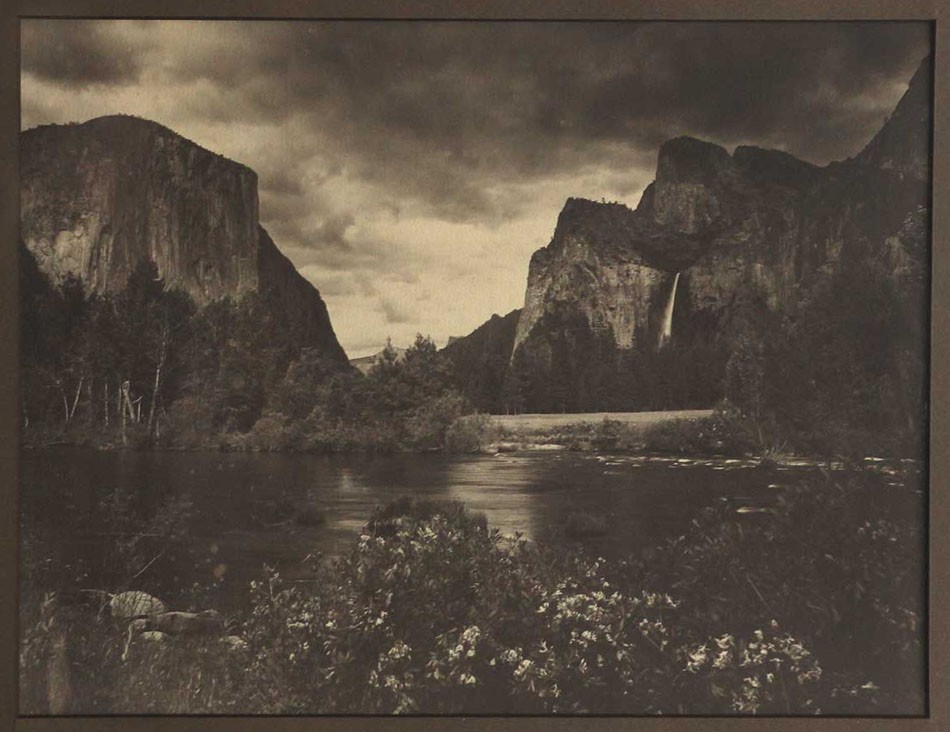

“A Holbein Woman”: Frances Stebbins & Mary Electa Allen, American: 1854-1941 & 1858–1941. Gelatin silver print ca. 1890: 20.1 x 16.3 cm laid down on light gray card mount 35.2 x 27.8 cm: presented here in original ca. 1896 beaded wood frame by Greenfield, MA framer Dunklee & Freeman with original overmat replaced. Done with the intent of being a tribute imitation painting to Hans Holbein’s “Portrait of a Woman from Southern Germany”, the subject of this portrait is the photographer’s mother Mary Stebbins Allen. (1819-1903) The result: “A Holbein Woman”, was one of the earliest and most successful examples of portraiture done by the Deerfield, MA sisters. From: PhotoSeed Archive.

Another words, if being accurate to revisionist history but without the convenient addition of a famous name, (2.) the Allen sisters efforts in the modern day might conceivably be retitled “A Formerly Attributed Woman” rather than “A Holbein Woman”.

And although it is but one example reanimated from that era using new technology, it seems reasonable to conclude 21st Century progress courtesy of Deep Nostalgia™ may only reinforce and belie a continuation of certain prejudices and expectations from the past, the same criticism that could be leveled at video driver technology being only an approximation of humanity, leaving us devoid of the true mannerisms of those who actually lived.

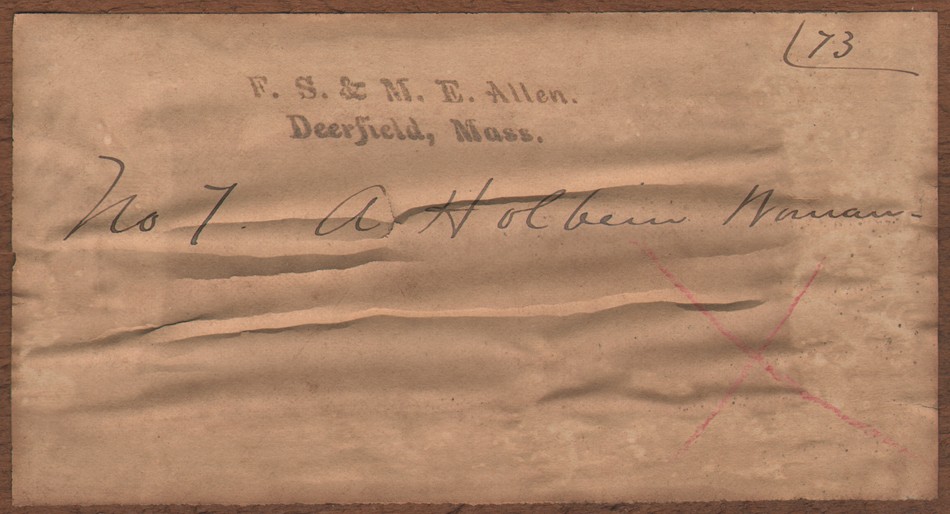

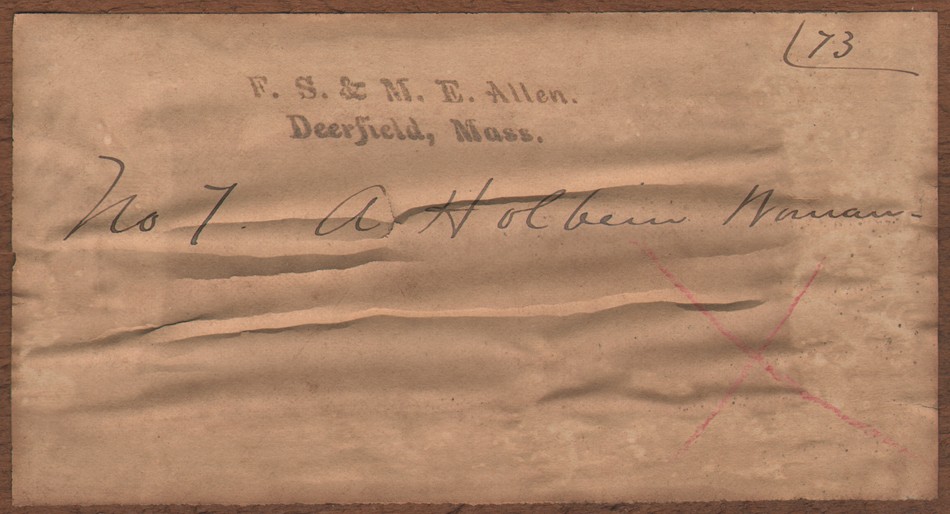

Exhibition label: “A Holbein Woman”: ca. 1896. Pasted white-paper label (7.2 x 13.6 cm) (preserved and cut out from) wood backing board with black ink photographers stamp: F.S. & M.E. Allen. Deerfield, Mass.; in black ink believed to be in the hand of the photographers: No 7 A Holbein Woman: 73 to upper right corner, faint X mark in red ink in lower right. From: PhotoSeed Archive

“Creepy” is one online descriptor I kept encountering in people’s reactions to this new technology, but when has that ever stopped “progress”? (3.) Are we doomed or can fleeting perceptions of the past in old photographs brought to “life” change our future for the better, our marveling reactions to it as incidental as the new shiny object of the here and now? Only time will tell. (4.) David Spencer-

Notes:

1. The worldwide pandemic brought on by COVID-19 lockdowns inspired a massive revival of imitation paintings and other works of art including photography. Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum in March, 2020 promoted their Stay at Home Challenge!, inviting people to recreate modern day reinterpretations from masterworks in their collection. This was soon followed by the Getty museum in California. One of the very first “challenge” accounts to promote this revived genre was the Netherlands Instagram account Tussen Kunst & Quarantaine– translating to “between art and quarantine” which first inspired the Rijksmuseum challenge.

2. This would never happen.

3. An examination of ethical concerns as a result of so-called Deepfake technology contained within Deep Nostalgia™ is explored in a New York Times article written by Daniel Victor from March 10, 2021: Your Loved Ones, and Eerie Tom Cruise Videos, Reanimate Unease With Deepfakes.

4. That shiny object has been here since February, 2021. Care to upload a selfie, historical photograph or stock pic of Kim Jong-un, Mao Zedong or Joe Biden and see yourself or them “sing” to popular music? Then download the WOMBO app here. Guardian technology columnist Helen Sullivan reports on March 12, 2021 the app just might be giving competition to Deep Nostalgia™.