“They were up in the attic of the house in an old art box.”…

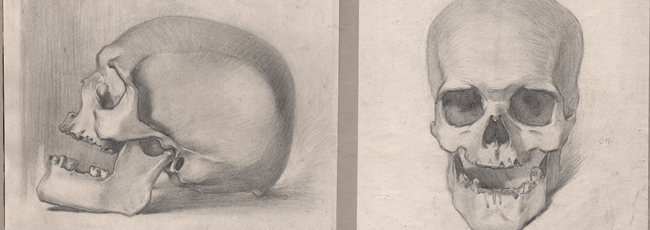

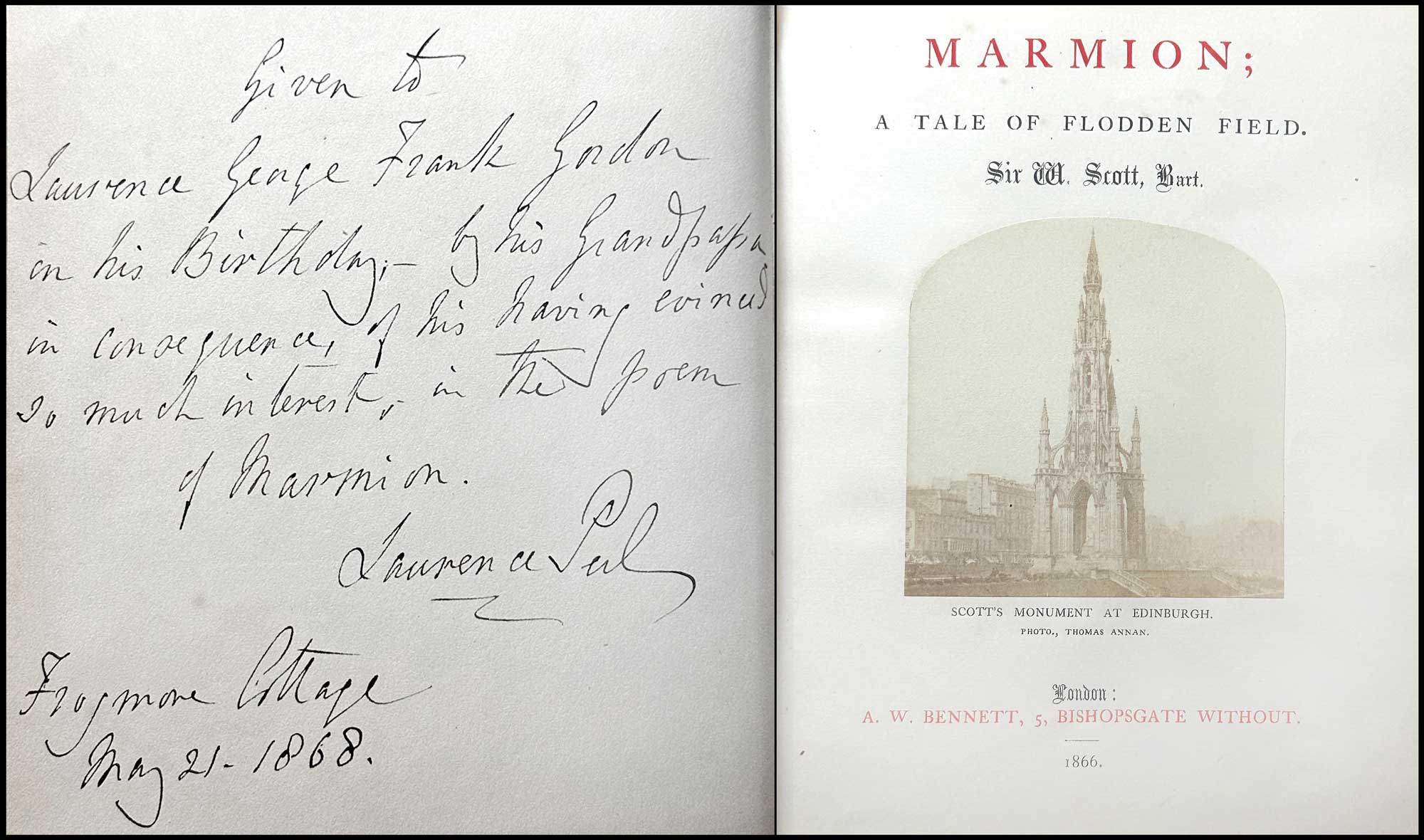

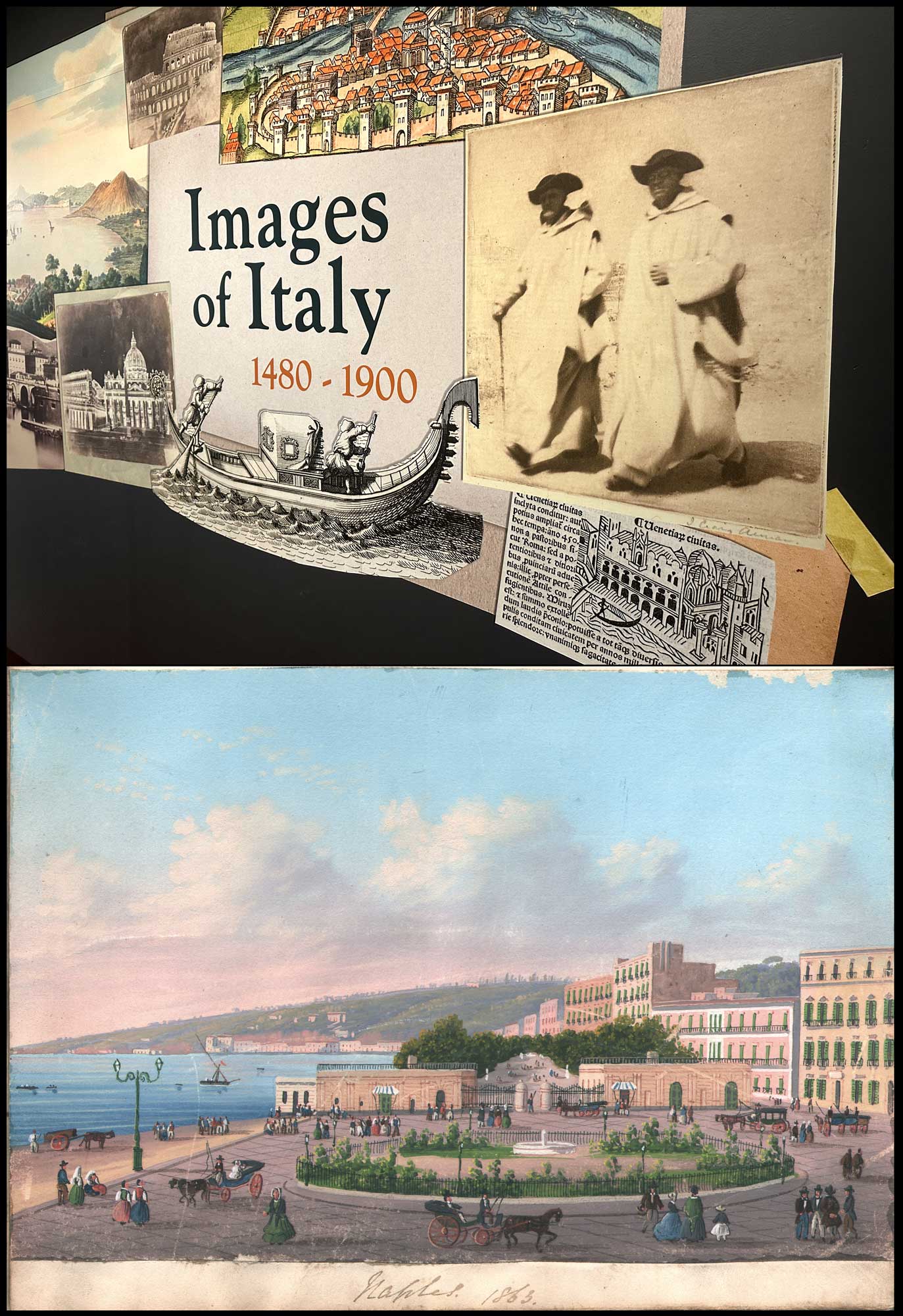

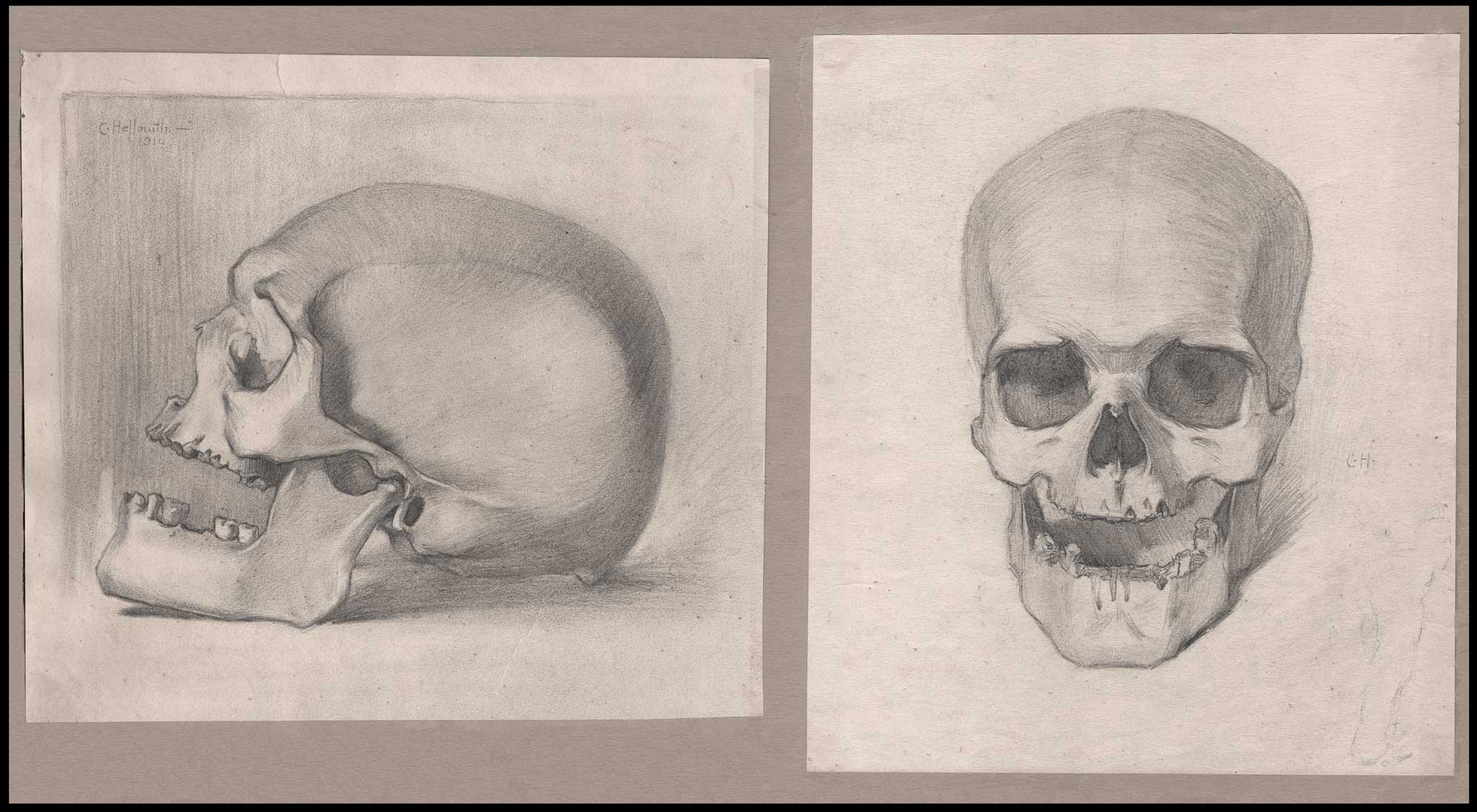

Skulls: Diptych: 1910, graphite on paper, Charles A. Hellmuth, American, 1887-1945. L: “Human Skull, Profile View”: 25.8 x 29.3 cm, R: “Human Skull, Frontal View”: 28.5 x 25.0 cm. Both laid down on oversized paper sheet: 37.9 x 61.5 cm. These two finely rendered views of a human skull were completed by the artist in his final year as an art student at the prestigious Art Academy of Cincinnati, then under the management of the Cincinnati Museum Association. From: PhotoSeed Archive

The above quote is a common refrain I hear when inquiring about artistic provenance. Or basement. But hardly ever: “They were (for our purpose: old photographs) hanging on the living room wall”. Of course, this particular artist ⎯ Charles A. Hellmuth (1887-1945)⎯ the subject of today’s post, was one of the lucky ones. His son, Joseph Foote Hellmuth, made the wise decision to hold on to a few choice remnants of his father’s artistic legacy before age forced his hand.

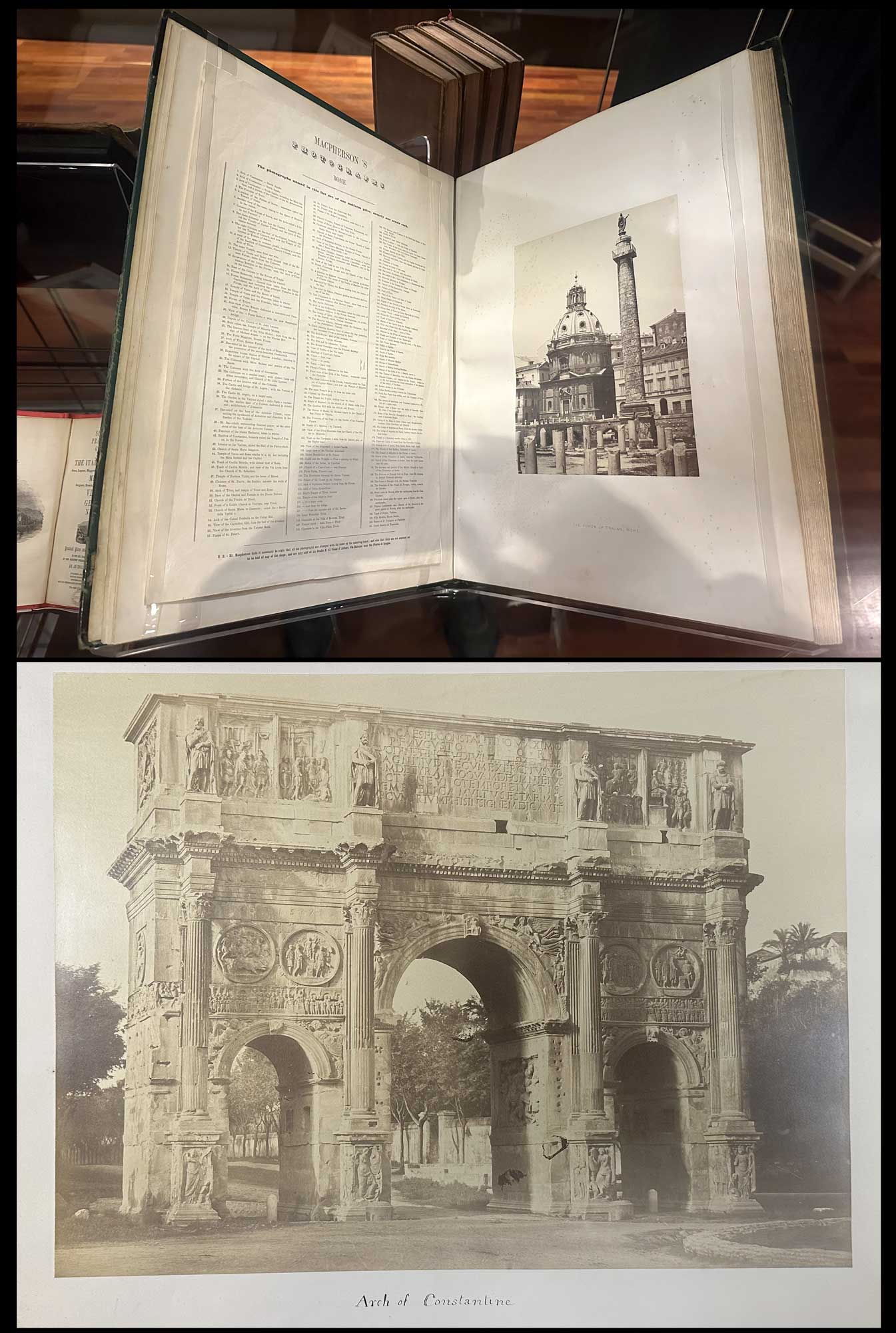

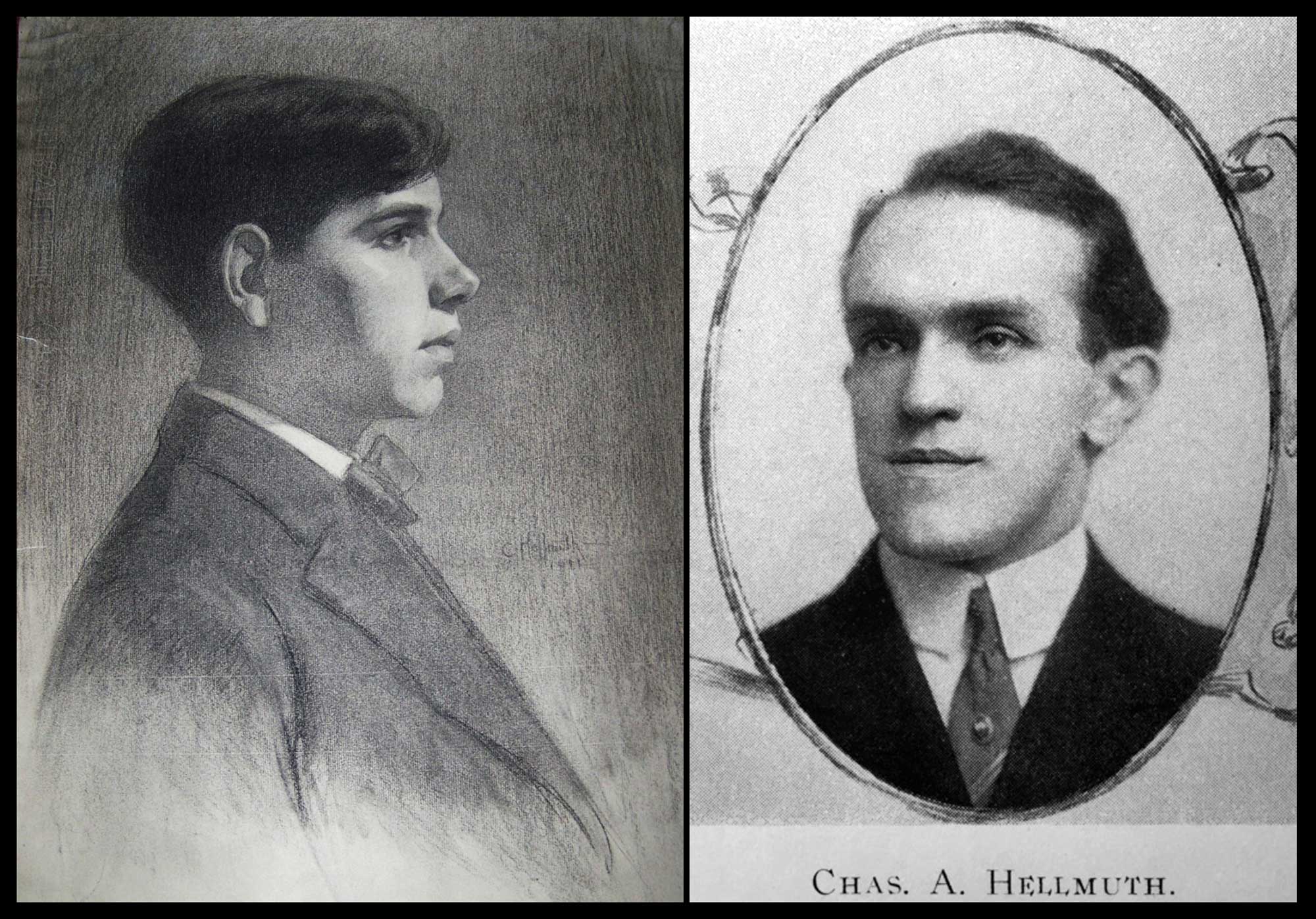

L: Self-Portrait? This charcoal |graphite on paper profile portrait of a young man by American artist Charles A. Hellmuth is dated 1911 (16 1/2″w x 22 1/2″h) and was described by its seller as a self-portrait of the artist. From: Private Collection. R: At twenty five years of age, class artist Charles A. Hellmuth is shown the year he graduated in 1912 from East Night High School, Cincinnati, OH. Along with this halftone photograph from The Rostrum, the school yearbook, were these insights: “Our able artist formerly attended Chillicothe High School, and entered our ranks in 1911. We were indeed very fortunate to have him with us, for his skill in art and valuable suggestions have aided us materially in making this book a success. He has always been recognized as a diligent and thoughtful student, and we are proud to claim him. We find him a very considerate and ever willing fellow, who has never failed us when called upon.” Source: web

No bother. Rescue is an archive speciality. Concerning examples of Hellmuth’s artwork and photographs I was able to procure in 2012, the online dealer from a northwest Rochester, N.Y. suburb I purchased them from added this little nugget after explaining his business was estate clean outs:

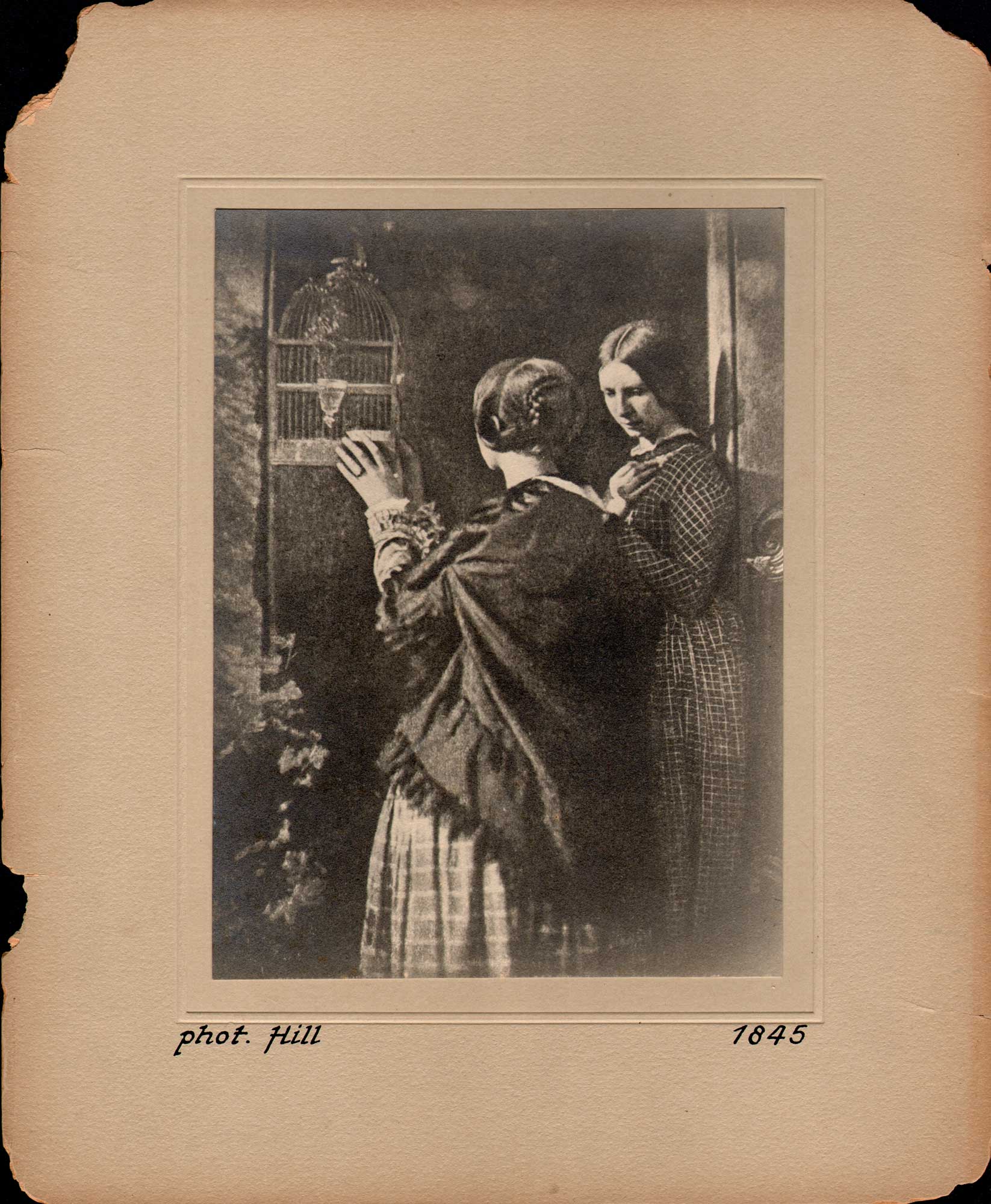

“Study of Miss A.”, Charles A. Hellmuth, American, 1887-1945, 1921, gelatin silver print: 24.4 x 19.3 cm on mounts: 26.7 x 20.4 | 42.9 x 35.5 cm. This figure study of a young woman clutching a flower bloom from a vase was entered in the inaugural October, 1921 exhibition of the Art Center, Inc., based in New York City. The purpose of this collective organization or movement was to “advance the Decorative Crafts and the Industrial and Graphic Arts of America” according to a pasted exhibition label on mount verso. From: PhotoSeed Archive

“Many of the photos in the house were taken by the real estate agent before we got there !! I was told she sold them to the local museum for ALOT of $$$ !! I was pretty upset.”

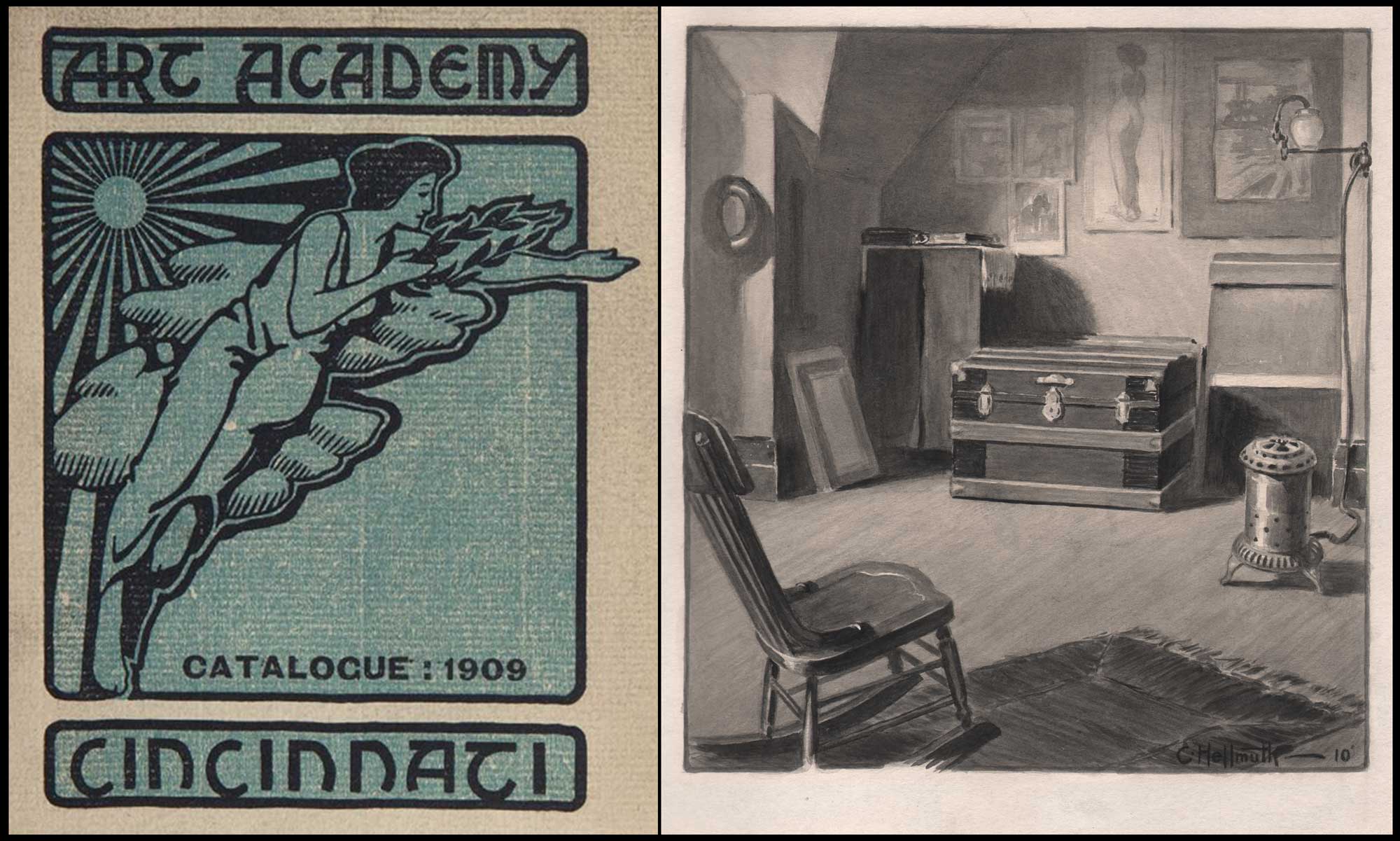

L: Cover Design: “Art Academy of Cincinnati Catalogue, 1909”, two-color woodcut on laid paper. At this time, the faculty chairman of the academy was Frank Duveneck, (1848-1919) an important American artist known to Whistler and John Singer Sargent. Source: Web. R: “Artists Garret”, Charles A. Hellmuth, American, 1887-1945, 1910, pen & ink drawing on illustration board, 22.8 x 21.0 | 35.4 x 31.2 cm. With drawings and paintings decorating the background wall; along with the essentials of bare-bones living- a large steamer trunk, kerosene heater and rocking chair- it might seem reasonable the artist used his own living space as the subject of this drawing, executed in the final year he attended the prestigious Art Academy of Cincinnati. From: PhotoSeed Archive

Certainly a great story, but I’m more inclined to believe the dealer was just trying to tell me what he thought I wanted to hear. After all, Charles Hellmuth is a complete unknown. Know any museums purchasing anonymous works off the street for big money? Do tell. (me) I should know, I’ve been fortunate to sell a few choice works from PhotoSeed to several important American museums and institutions, as well as internationally, and always extend our invitation to those overseeing collections and other informed collectors seeking original material.

“Man with cane Walking away from Building”, Charles A. Hellmuth, American, 1887-1945, 1905, unmounted charcoal drawing on laid paper watermarked MICHALLET, 27.5 x 40.3 cm. This is an early drawing study executed by the artist in his first full year attending the prestigious Art Academy of Cincinnati. From: PhotoSeed Archive

Speaking of acquisitions, the process is exacting. Museum registrars are fastidious, and endowed money for rare photographs simply does not grow on trees- especially since the current unfortunate trends include deaccessioning works in order to provide collections the ability to keep the electricity on and front doors open. Committed benefactors, promised gifts and bequests make up the bulk of new work entering museums.

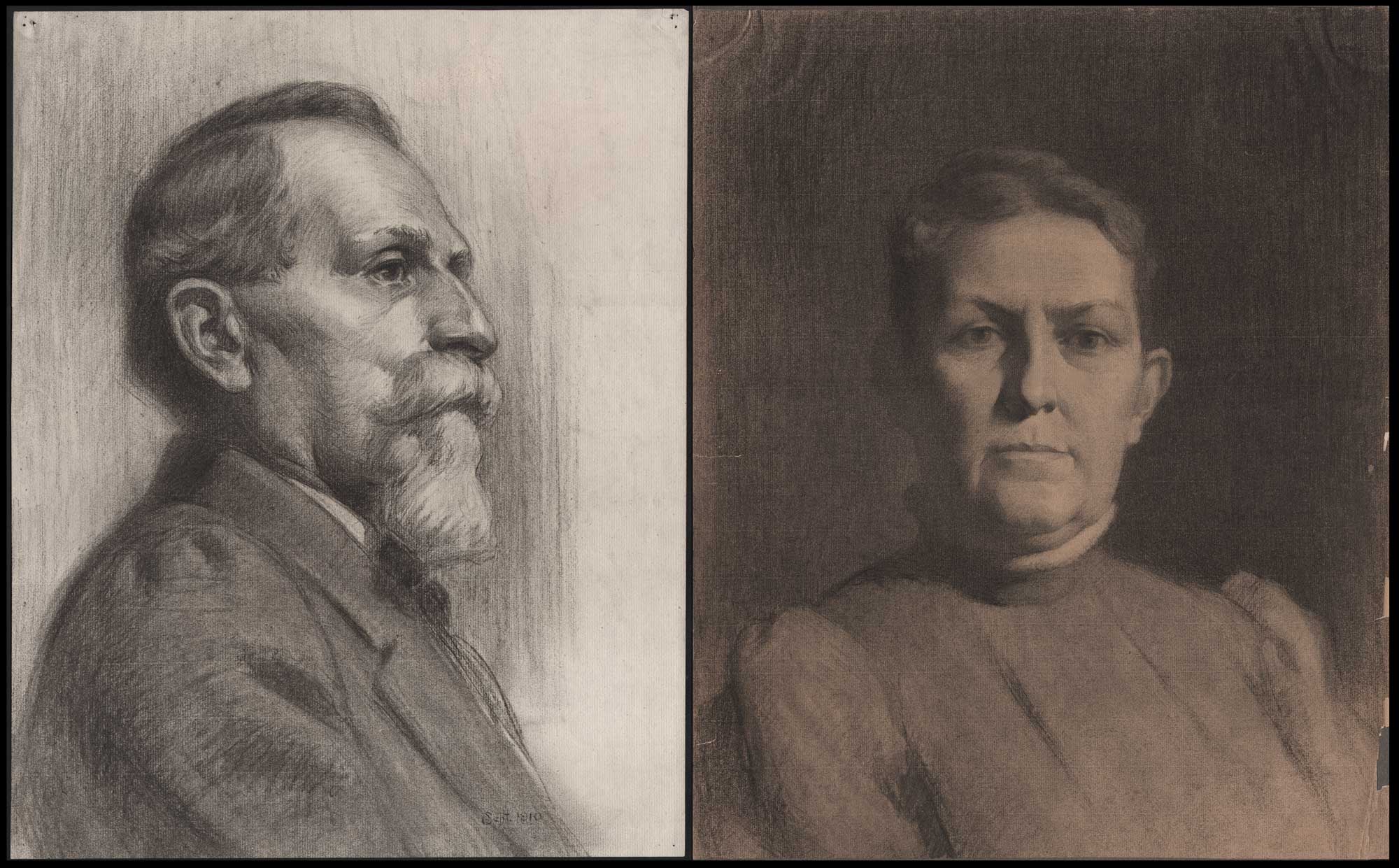

L: “Profile of Older Gentleman with Beard”,Charles A. Hellmuth, American, 1887-1945, (unsigned) dated “Sept. 1910”, unmounted charcoal drawing on laid paper, 42.8 x 34.0 cm. R: “Portrait of Older Woman”, Charles A. Hellmuth, American, 1887-1945, ca. 1910, charcoal drawing on laid paper tipped to backing board, 42.8 x 34.0 cm. These two fine drawings may very well depict the artist’s own parents, who each would have been around 60 years of age. Joseph Hellmuth Jr. (1850-1939) was a commercial painting contractor and spouse Anna Mary Rudman Hellmuth (1855-1940) was a homemaker. From: PhotoSeed Archive

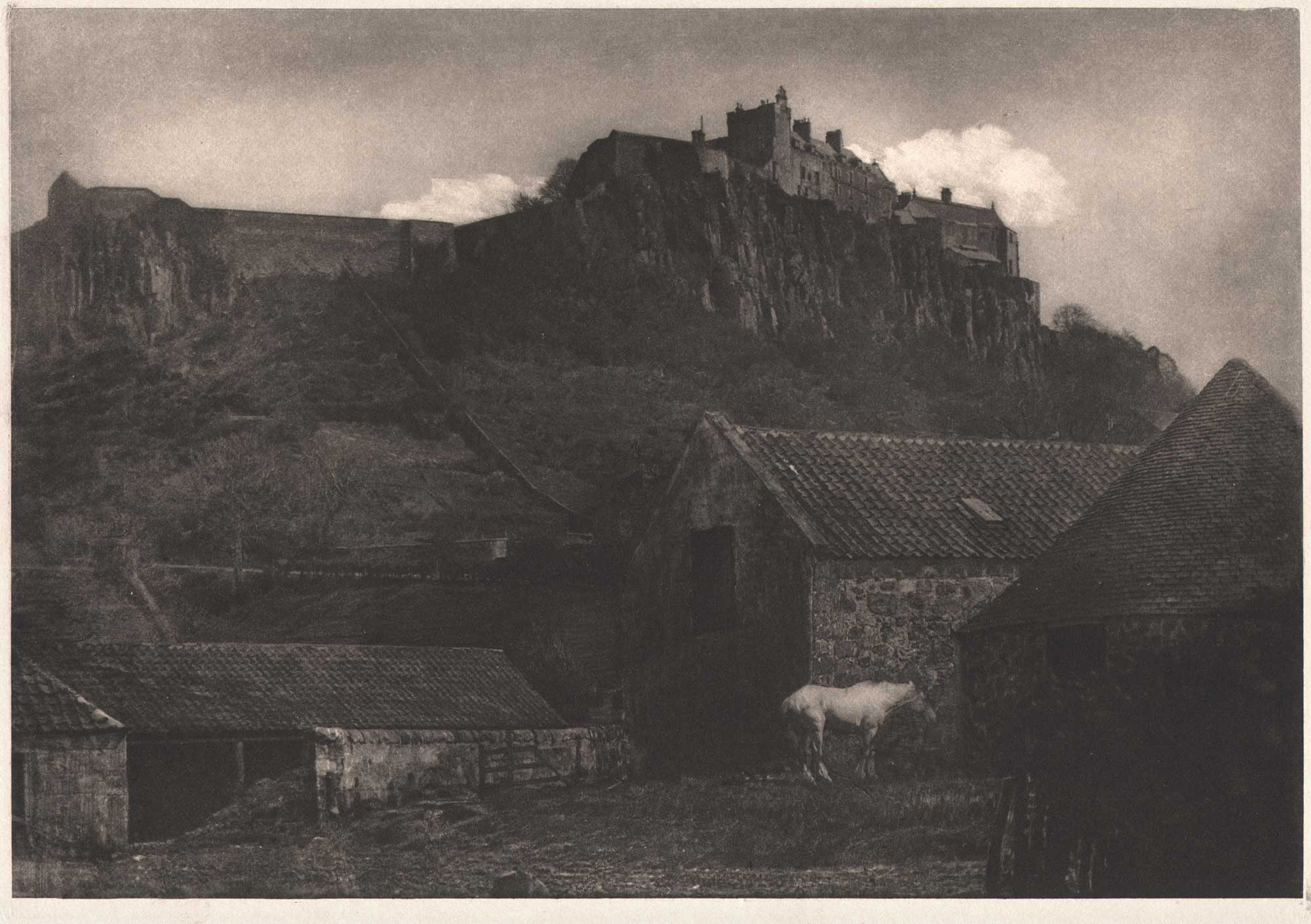

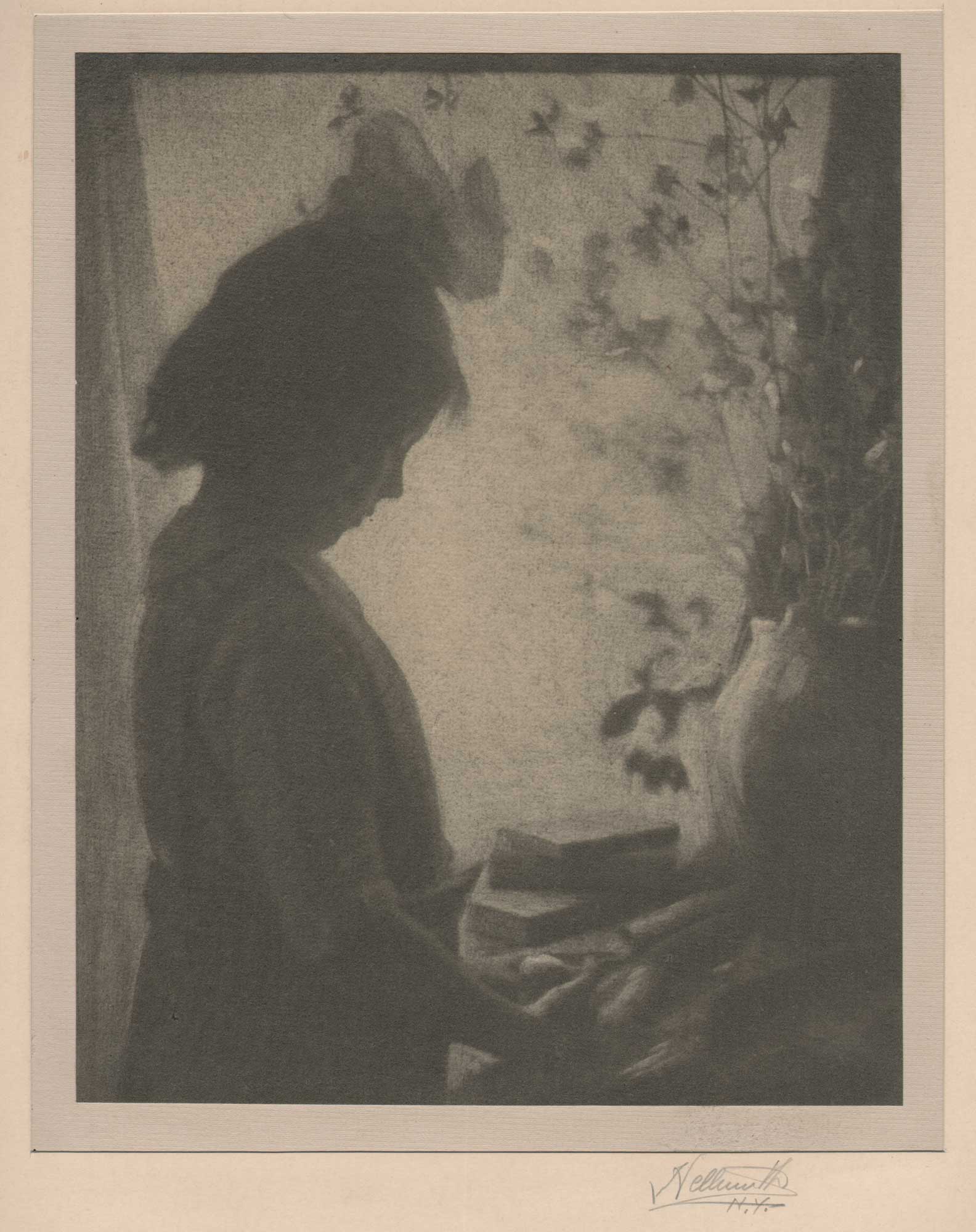

“Silhouette”, Charles A. Hellmuth, American, 1887-1945, 1923, multiple gum-bichromate print on laid paper, 24.5 x 19.4 cm on mount: 35.5 x 27.9 cm & window matting: 50.8 x 40.6 cm. This exhibition print shows a young girl with hair bow silhouetted against an interior window. Perhaps dating to as early as 1920, it was exhibited in the 1923 Pittsburgh Salon as well as the International Salon hosted by the Pictorial Photographers of America in New York City, May, 1923. From: PhotoSeed Archive

But in the meantime, stories and lives can be retold- often for the first time, via the rescuing process- the heck with that ol’ dustbin of history notion! The pollination of photographers embracing the easel and the somewhat less common trend of artists embracing the camera concerns the subject of this post. Our artist, Charles Hellmuth, I would discover, was someone who might be called a journeyman artist. His interest in amateur photography, as it turned out, was only a short obsession: probably less than five years, from 1920-25.

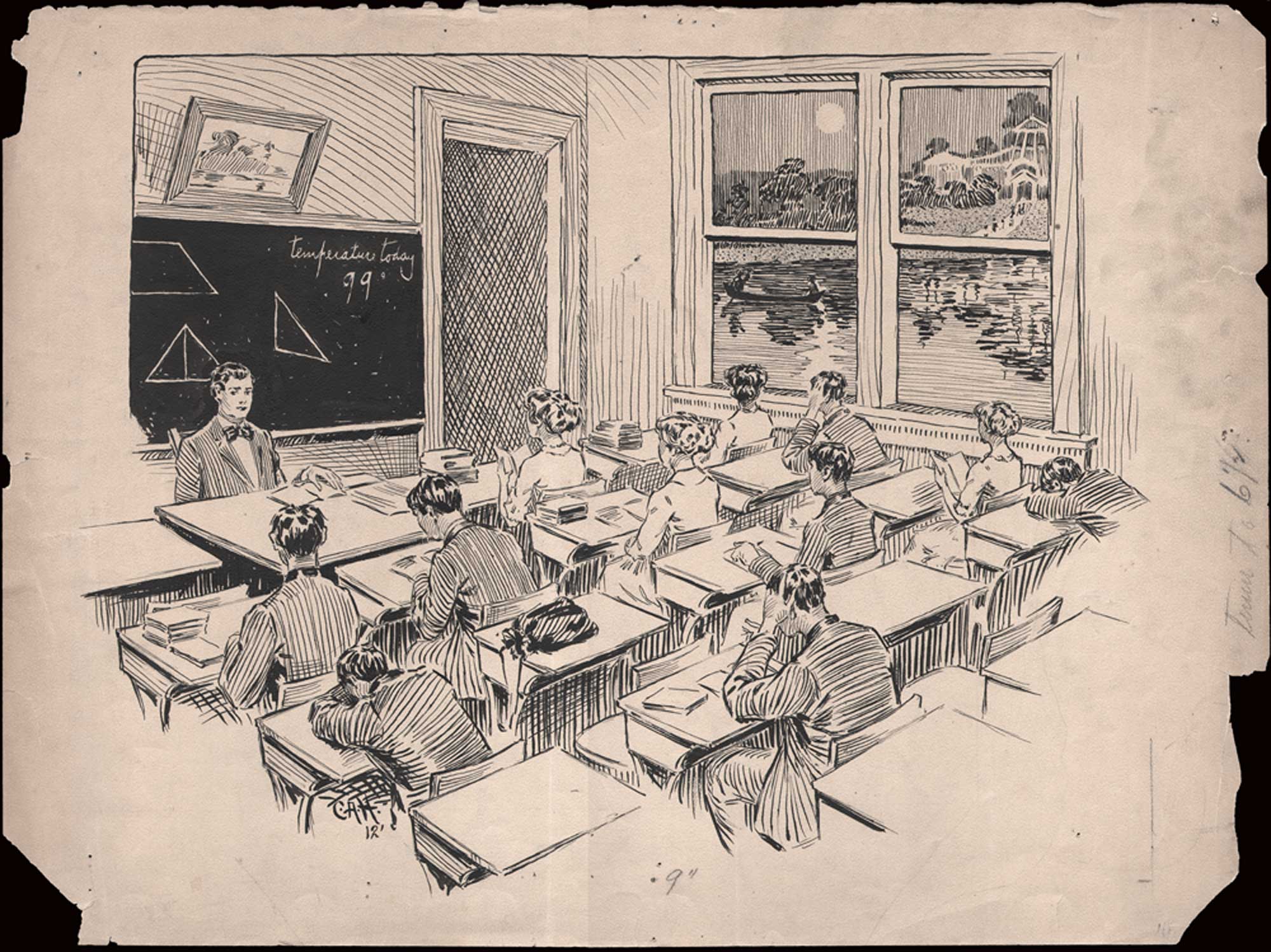

“When the Days Grow Long”, Charles A. Hellmuth, American, 1887-1945, 1912, unmounted ink drawing on oversized paper, 38.2 x 51.5 cm. This work was published in 1912 as a full page illustration in the artist’s class yearbook, The Rostrum, for East Night High School, Cincinnati, OH. Hellmuth was the class artist and earned an academic diploma when graduating from the school when he was 25 years old. From: PhotoSeed Archive

Born in northern Ohio in 1887 to first-generation parents, (his grandparents had immigrated from Germany to the US) Charles was undoubtedly influenced by his own father’s profession from a young age- that of commercial painting contractor. So think houses instead of canvases. With however the certain paternal decree that a skilled trade was necessary in order to support his future self and family, (Charles had five other siblings) the completion of his primary education for the younger Hellmuth at first did not lead to advanced schooling, at least not right away.

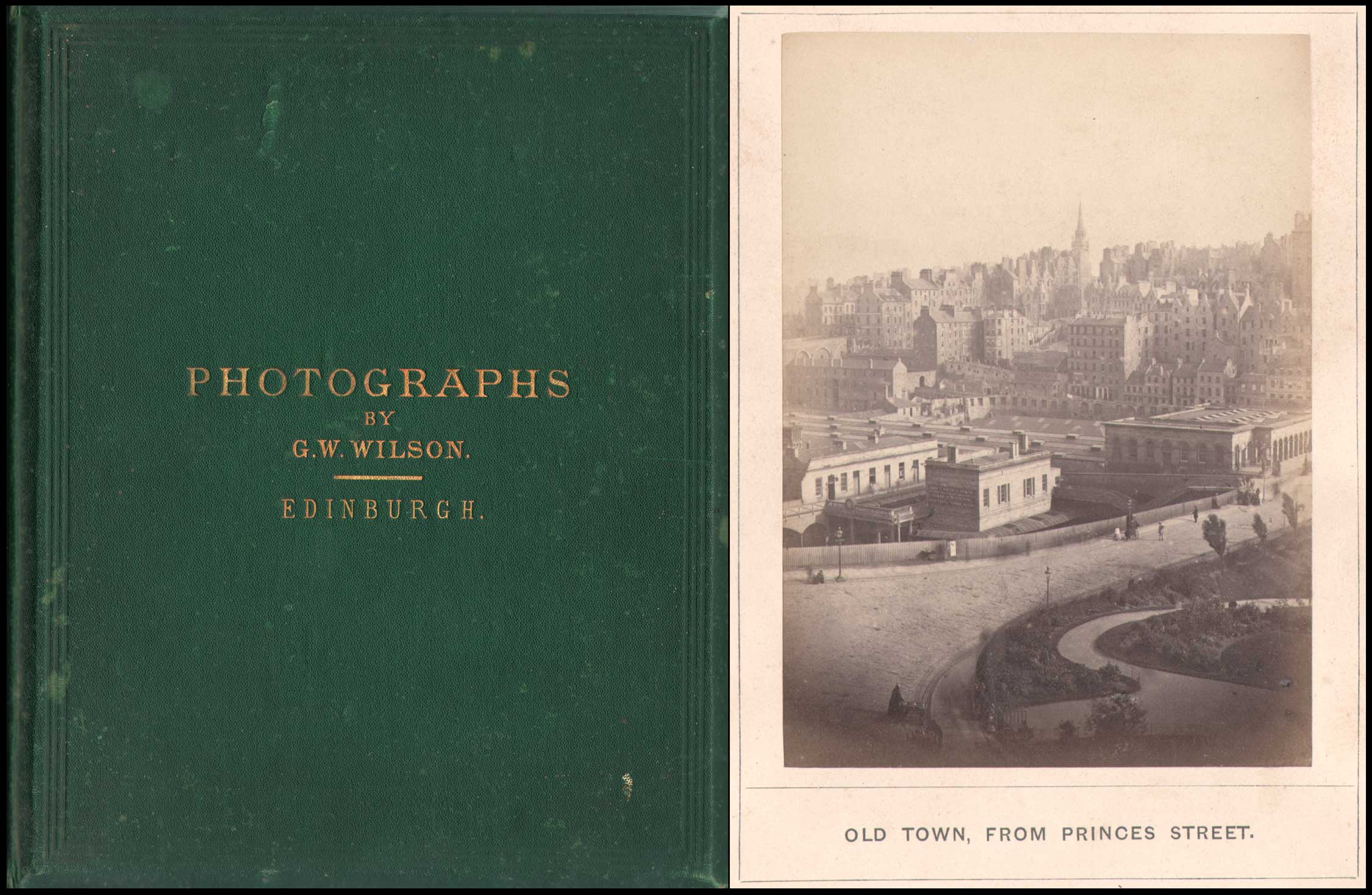

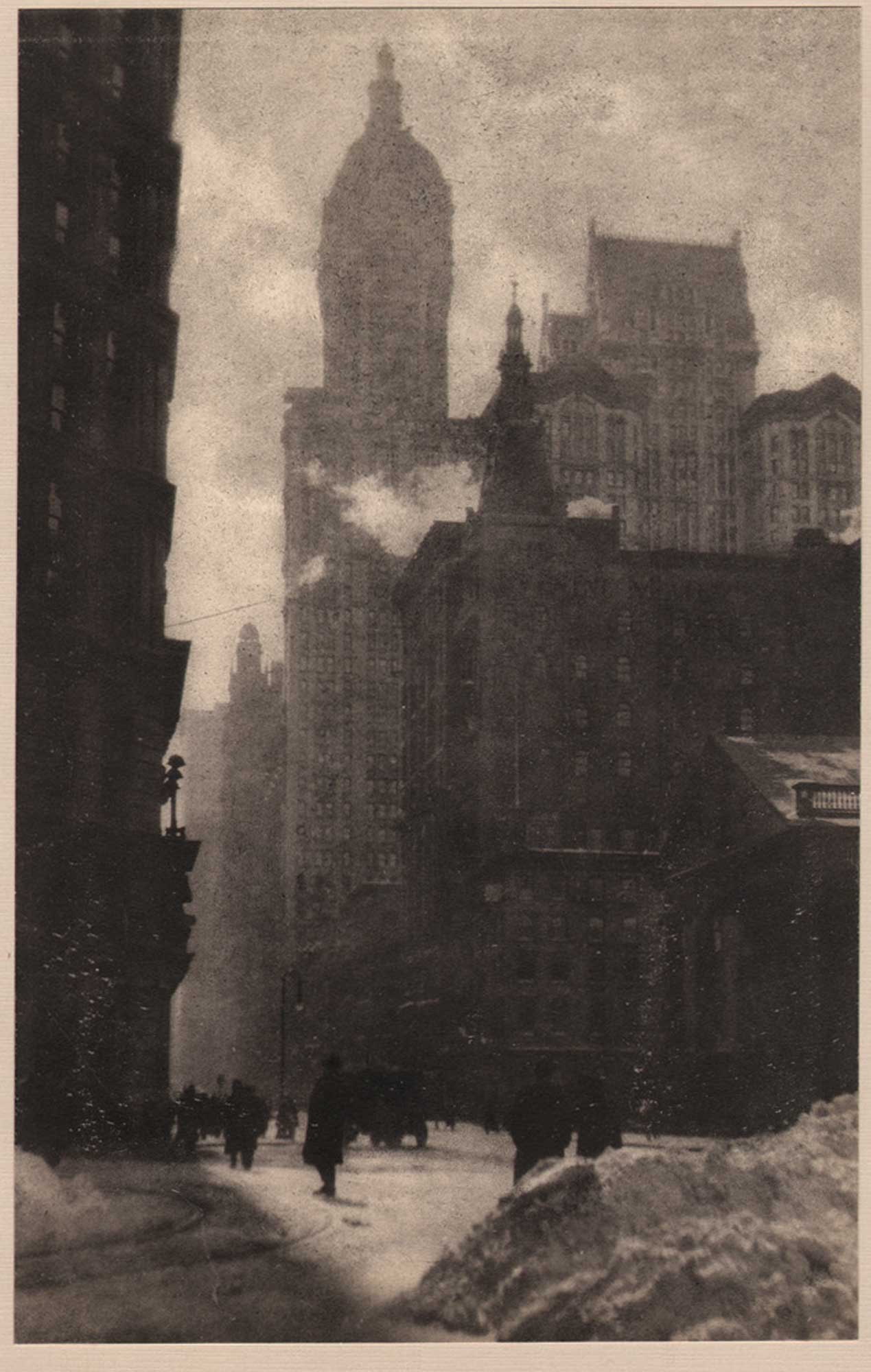

“Lower Broadway N.Y. City”, Charles A. Hellmuth, American, 1887-1945, ca. 1920, mounted bromoil print, 32.1 x 20.3 | 38.8 x 27.9 cm. In this winter scene showing Lower Broadway in New York City, the former Singer Building at center towers above all. For one year, 1908-1909, the Singer was the tallest building in the world at 612′. The former world headquarters of the Singer Sewing machine company, it was designed by architect Ernest Flagg. (1857-1947) Hellmuth was a resident of the city when he took this view, living at 338 W. 22nd St. From: PhotoSeed Archive

Instead, the 17 year old somehow discovered he possessed actual artistic talent. The jackpot? In late 1904, he matriculated at the prestigious Art Academy of Cincinnati under their new faculty chairman Frank Duveneck, (1848-1919) an important American artist in his own right known to Whistler and John Singer Sargent.

“Homestead in a Snowy Landscape”, Charles A. Hellmuth, American, 1887-1945, 1922, oil on unstretched canvas, 34.4 x 44.5 cm (overall). A rare surviving example of a painting by the artist. It’s unknown how prolific he was in creating works such as this, although he most likely used the medium of oil paint for some of the poster work he did for the commercial lithography firms he worked for. In 1918, he became a member of The Society of Independent Artists and like hundreds of others, paid a $6.00 entry fee to have several works displayed in their 2nd annual exhibition. From: PhotoSeed Archive

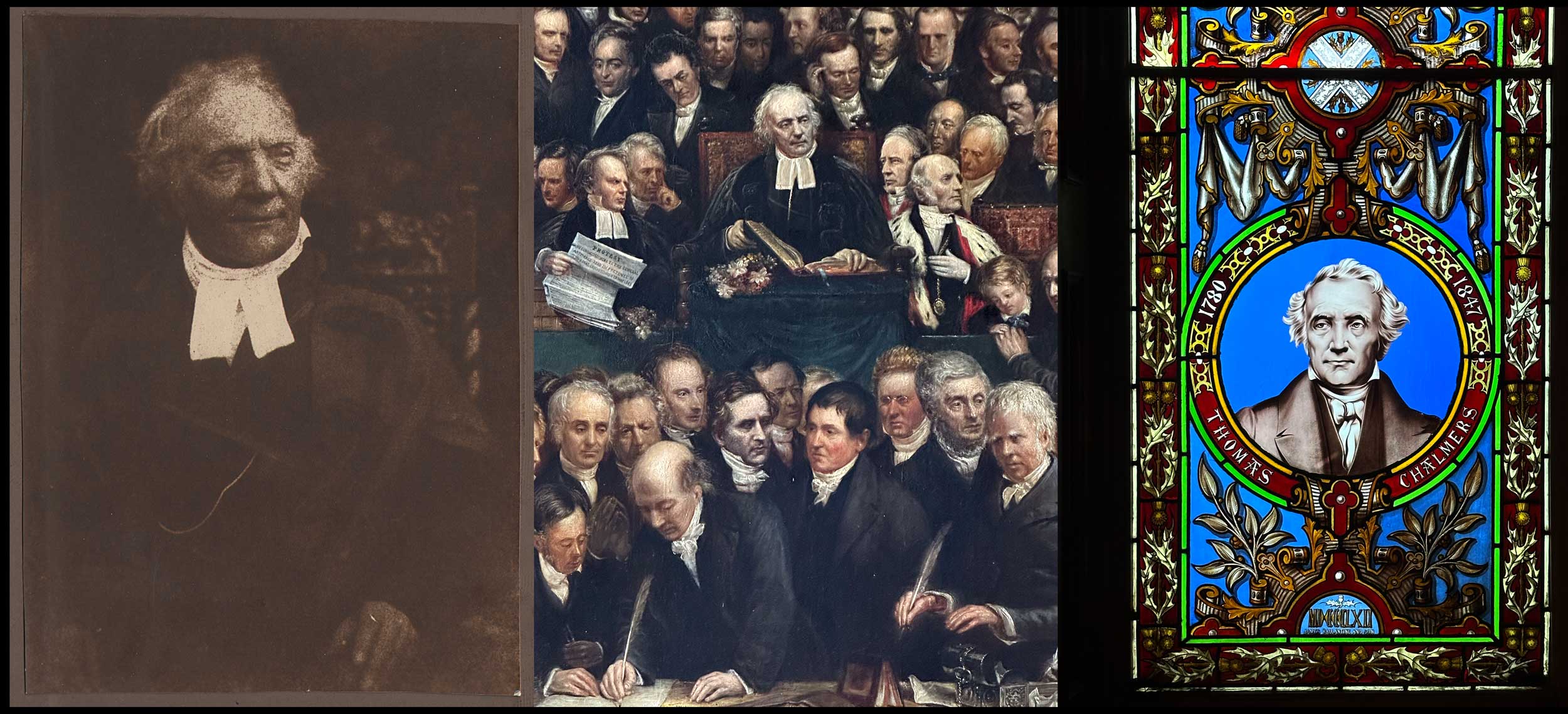

For the six years he attended the Cincinnati academy, we are fortunate to be able to share some of the young artists original student drawings. The diptych of human skulls leading off this post- a common art school drawing assignment, are finely rendered, as are two individual portraits of an older gentleman and woman who may well be Hellmuth’s own parents. With the knowledge he would eventually immerse himself by the early 1920’s with amateur photography, these works are a wonderful reference for his obvious skill set in embracing the very different mechanical aspects of the camera and chemical knowledge requirements of the darkroom.

But our artist was not done with schooling. Even though his occupation was listed as artist for the 1910 Cincinnati City Directory, he chose to attend Chillicothe High School in the town he was born the same year and then enrolled in 1911 as a night student at East Night High School in Cincinnati. This would give him the necessary diploma required to open the employment doors more easily for one primarily schooled in the art trade. When he finally graduated high school, at the ripe age of 25, the editors of the class yearbook said of him:

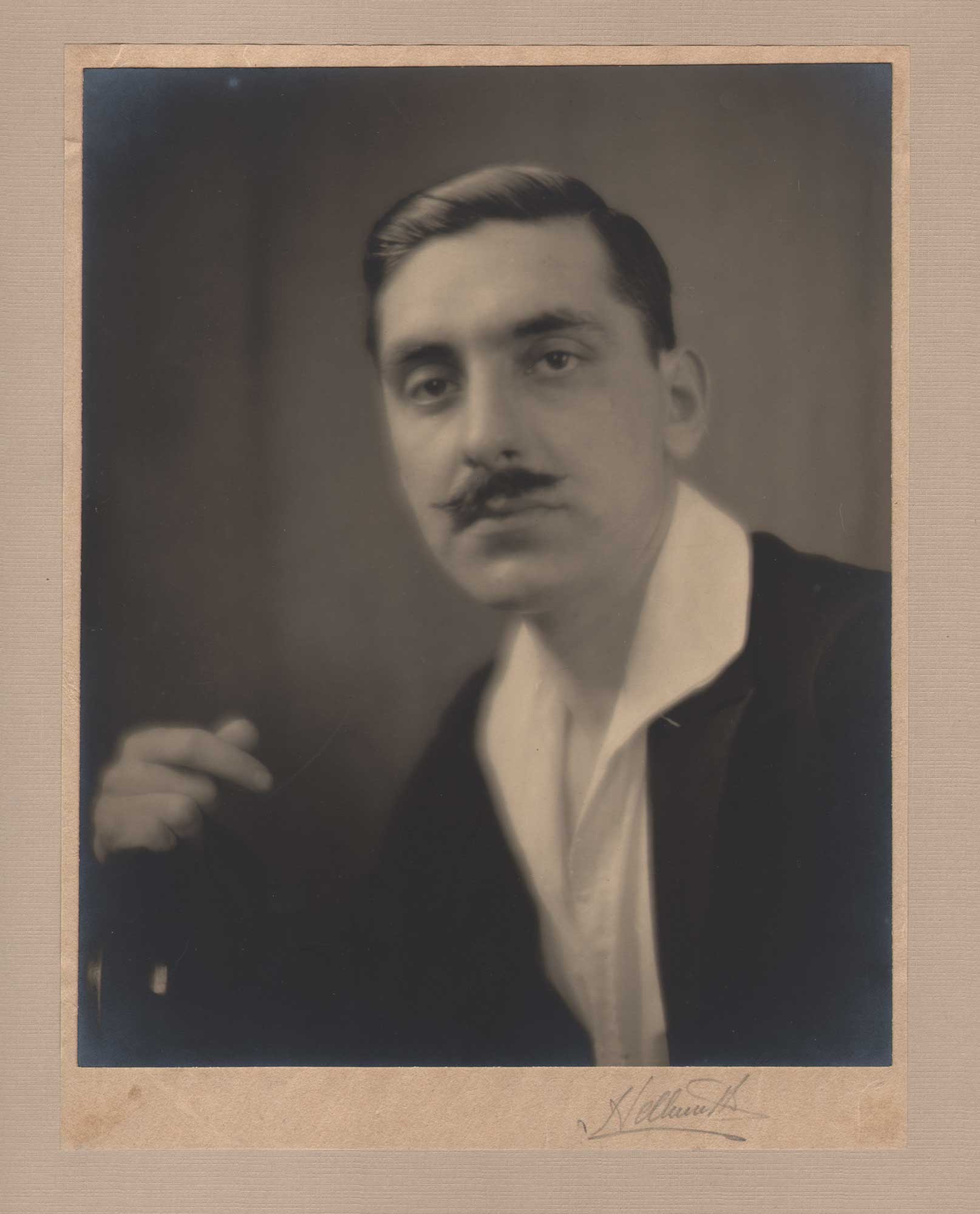

“Man with Mustache”, Charles A. Hellmuth, American, 1887-1945, ca. 1920-25, mounted gelatin silver print, 24.0 x 19.5 | 26.5 x 20.3 | 43.2 x 35.6 cm. A fine example of the artist’s portrait work, the subject bears a passing resemblance to the artist himself. Although lacking the NY attribution he sometimes included with his signature, its still most likely from the period he lived their while being an active member of the Pictorial Photographers of America. From: PhotoSeed Archive

“We were indeed very fortunate to have him with us, for his skill in art and valuable suggestions have aided us materially in making this book a success. He has always been recognized as a diligent and thoughtful student, and we are proud to claim him.”

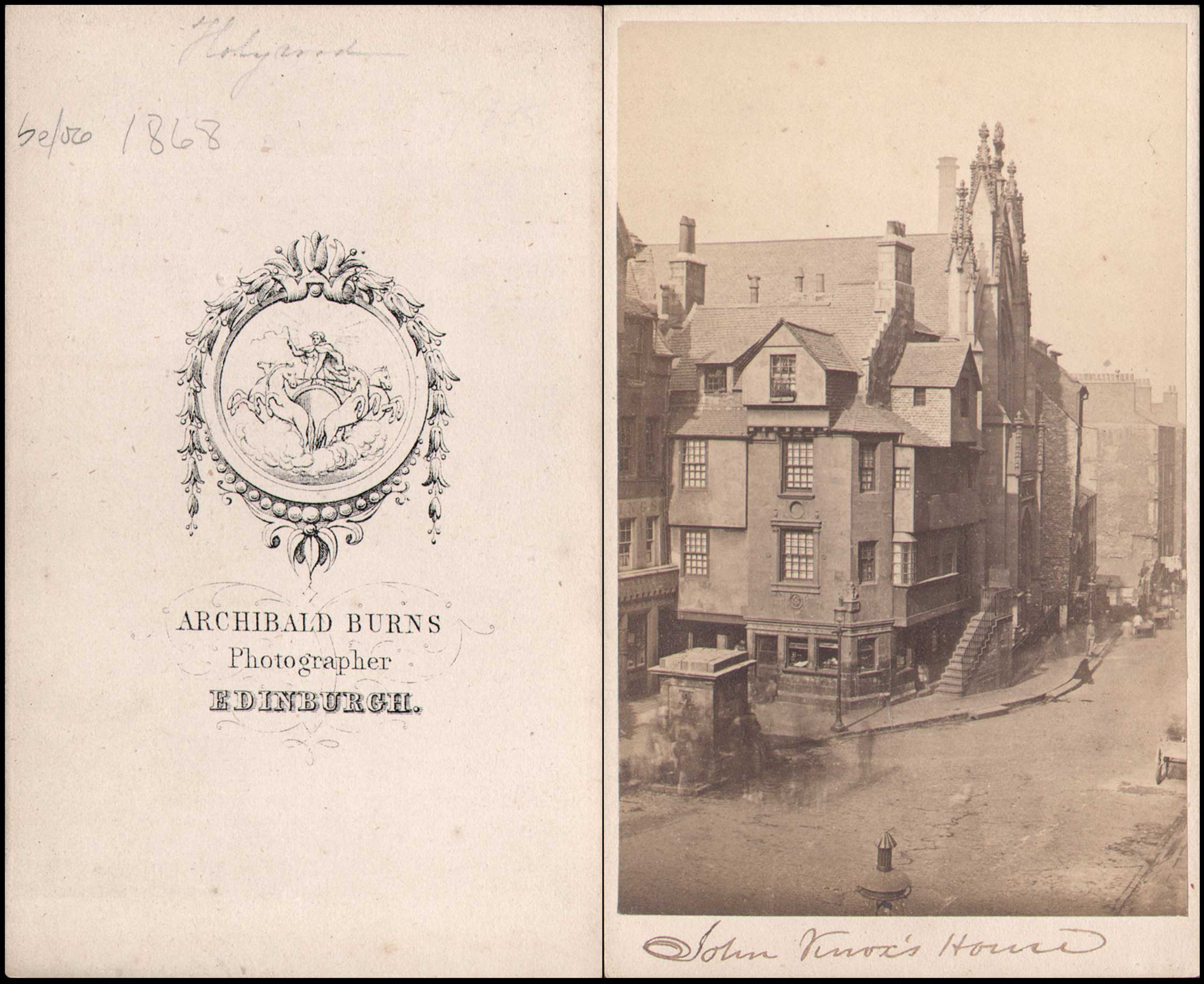

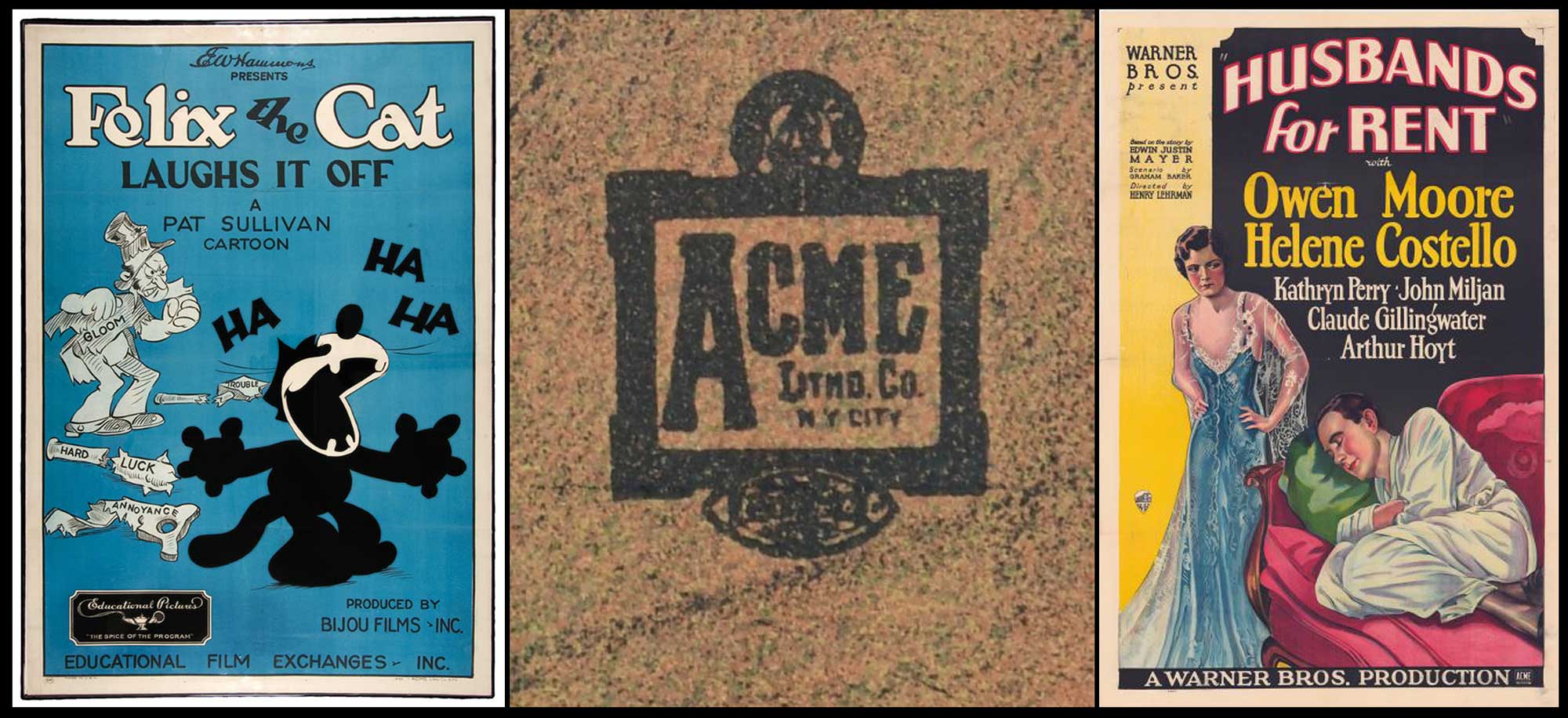

Charles A. Hellmuth worked as a commercial artist and lithographer for ACME Litho, from as early as 1917 to the mid 1920’s, and went on to work for Morgan Litho in Cleveland after this period. No extant posters or other advertising material produced by Acme or Morgan credited to the artist are known. L: “Felix the Cat Laughs it Off”, a 1926 animated short by Acme. M: closeup of ACME logo on ca. 1921 silent film poster “Franklyn Farnum” by Canyon Pictures Corp. R: “Husbands for Rent” Acme poster for 1927 romcom featuring Owen Moore and Helene Costello. From the web: “Acme Litho Company was initially used by Fox’s Box Office Attractions and Pathé (studios) in the teens. Acme also worked for Educational Film Distributors.” Source credits for all: Web

Ambitious, but apparently not of great health, (he claimed a medical deferment for a heart condition on his WWI draft registration) he eventually made a home in New York City, working as an artist and lithographer for the Acme Litho Company. It was in New York in the early 20’s that the artist fully embraced amateur photography, winning prizes and having his work-mainly bromoils- exhibited in the salons of the Pictorial Photographers of America, of which he was a member.

“At the Market”, Charles A. Hellmuth, American, 1887-1945, ca. 1920-25, mounted bromoil print, 19.8 x 28.2 | 32.2 x 40.3 cm with overmatt: 51.0 x 40.7 cm. A documentary image most likely taken in New York City shows a woman with oversized sun bonnet clutching her basket while eyeing grapes hanging in an outdoor produce market. The mount verso carries the white label for Member Pictorial Photographers of America and the artist’s NY address: 329 W. 22nd St. From: PhotoSeed Archive

It would have been interesting had Hellmuth stuck with photography longer, but with his marriage in 1926 and birth of his son Joseph in 1928, his free time was taken over more by family priorities. By 1930, they were back in his home state of Ohio where he would continue working as a lithographer and poster artist for Morgan Litho in Cleveland, a company that had bought out his former employer Acme.

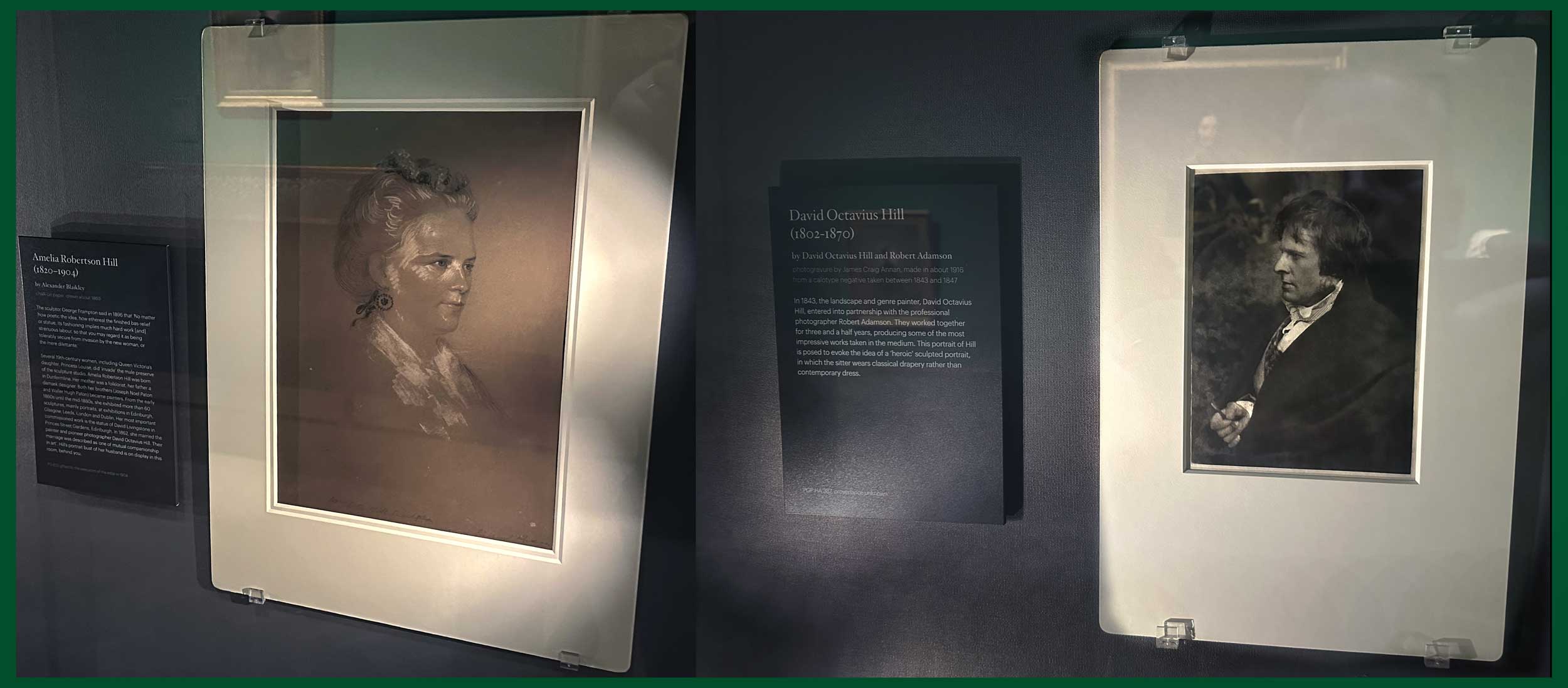

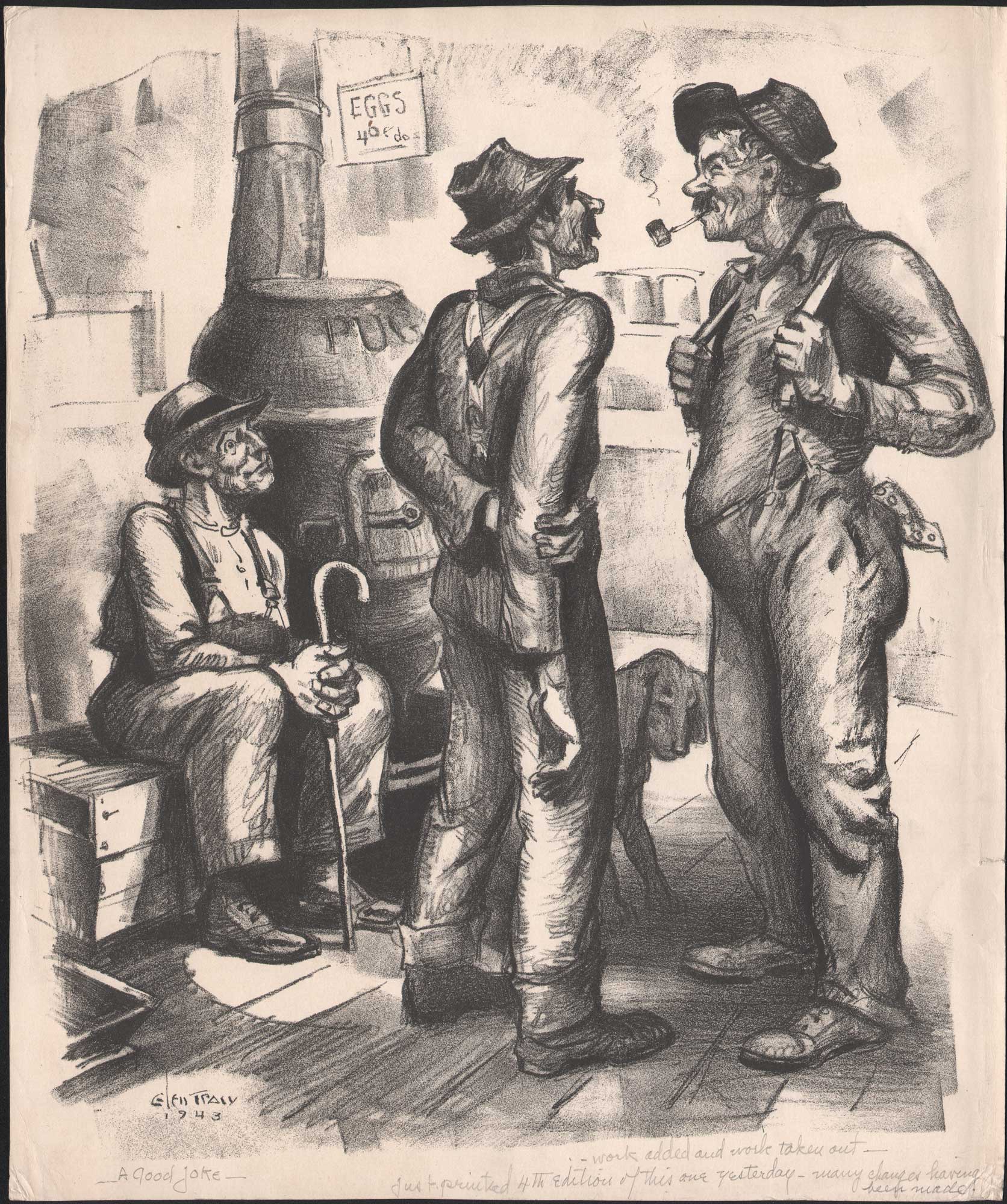

Fellow Students and Collaborators: “A Good Joke”, Glen Tracy, American, 1883-1956, 1943, unmounted lithograph on paper, 4th state, 37.2 x 31.0 cm. Glen Tracy and Charles Hellmuth were fellow students at the Art Academy of Cincinnati in the first decade of the 20th Century, becoming lifelong friends. Tracy also became an instructor in Preparatory Drawing, and Painting in Oil and Water Colors in 1909 at the Academy. This Tracy lithograph was turned into a lithograph by Hellmuth while he worked at Morgan Litho in Cleveland in the early 1940’s. Hellmuth has added his printing notes in graphite to the bottom margin and titled the work in his own hand: A Good Joke | -work added and work taken out – just printed 4th edition of this one yesterday- many changes having been made. From: PhotoSeed Archive

Apparently, with future evidence to be determined, Hellmuth never received artistic credit for the many posters, broadsides and other advertising material published by Acme and Morgan– a standard industry practice for the hundreds of anonymous artists plying their trade who would never see a byline working for these companies. In contrast, his photographs- beautifully composed with the hallmarks of a subtle palette of highlights and shadows enhanced by the bromoil process- would earn the public’s recognition in his lifetime.

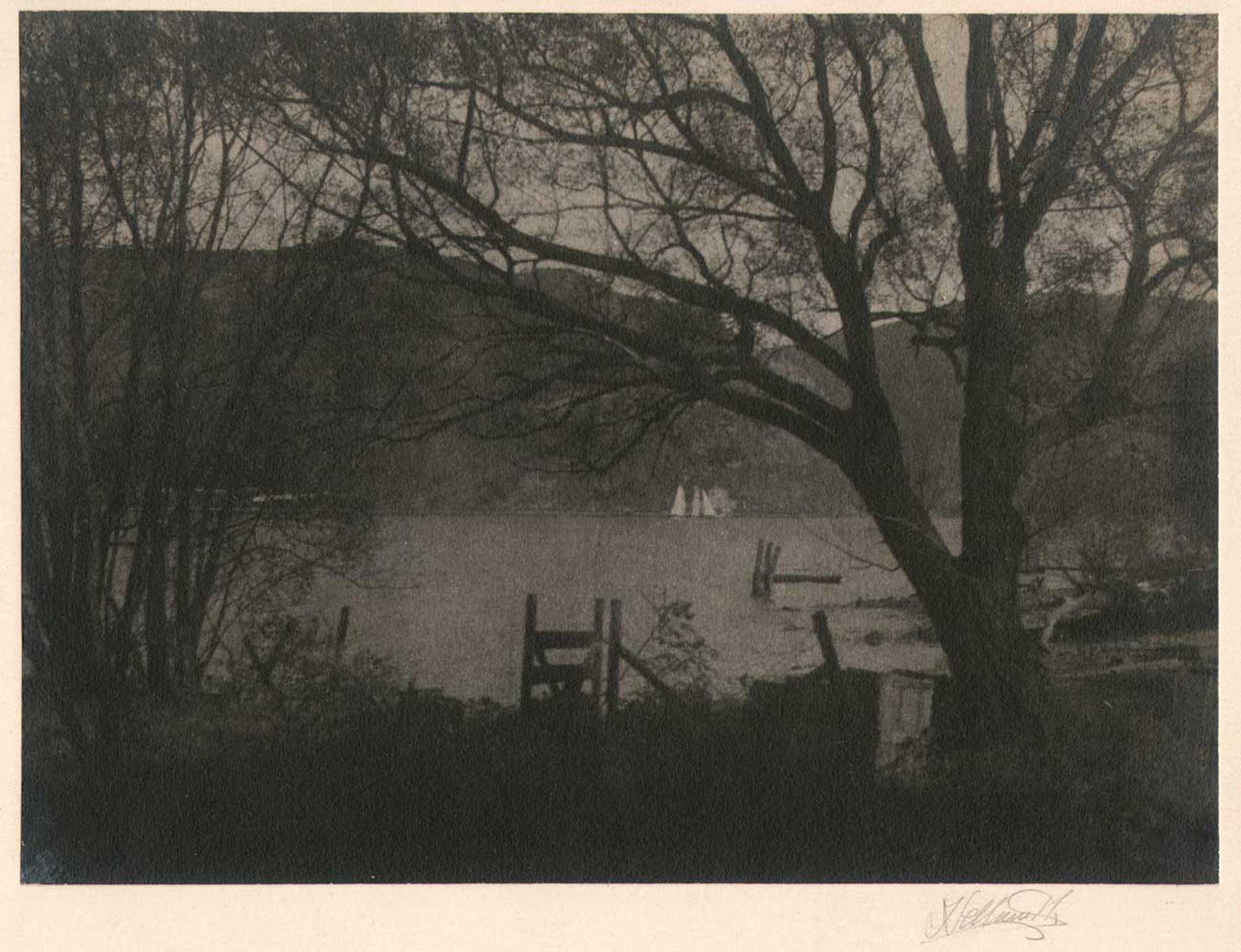

“Cornwall on the Hudson”, Charles A. Hellmuth, American, 1887-1945, 1923, mounted bromoil print, 17.4 x 23.7 | 29.5 x 36.5 cm. Sailboats on the Hudson River can be seen in the distance in this Summertime view most likely taken in 1922. It received an honorable mention in a monthly camera contest sponsored and published by Shadowland magazine for their February, 1923 issue. Judges comments included with the reproduction: “This is well composed with a pictorial quality“. From: PhotoSeed Archive

This balance of a career trade and amateur craft surely satisfied his artistic drive, and reason enough his proud son chose to preserve the evidence of his father’s career- squirreling it within an old art box in the attic of his Rochester, N.Y. home. Memento memories rescued and showcased here for your consideration and delight.

Historical Biography: Charles Andrew Hellmuth 1887-1945

1887: Born on January 17th in Chillicothe, OH to father Joseph Hellmuth Jr. ,(1850-1939) a commercial painting contractor, and mother Anna Mary Rudman Hellmuth, (1855-1940) a homemaker.

1904-1910: Seeking a trade, he enrolls in late 1904 at the age of 17 at the Art Academy of Cincinnati, then under the management of the Cincinnati Museum Association.

1907: Student living in Cincinnati and attending Art Academy of Cincinnati. (1907 Directory)

1910: In his last year at the Academy, he lists himself as an Artist living at 2153 Fulton Ave., Cincinnati. (1910 Directory)

-Enrolls in Chillicothe High School in the Ohio town he was born.

1911: Perhaps desiring to be closer to the city of Cincinnati where he earned his art diploma and to be closer with friends and professional acquaintances, he matriculates at East Night High School in Cincinnati, OH, living at 1927 Auburn Ave. in Mt. Auburn, OH. As its name implied, East Night was a night school, where students worked during the day and attended class at night. Although born in Chillicothe, his first-generation parents- also born in Chillicothe, whose parents both immigrated from Germany- had a large family of six children to support. Because of these family obligations, dedicated students such as Hellmuth graduated older. At East Night, many graduates took courses in Bookkeeping and Stenography- trades with good career outcomes. Additional information from Fulshear Books, Whiting Texas: “Some history on East Night High School from the Withrow High School Alumni Association site: “East Night High School was in existence from 1911-1937 and classes were held in the East High School building and eventually the Withrow High School building. It was intended for students that could not attend day classes due to necessary working conditions, family care concerns or for any reason that daytime classes were not an option for individuals who wanted a high school education.”

1912: Graduates from East Night High School on May 24, listed as the Class Artist. He had participated in the school’s Oratorical Contest and gave the speech: “The Value of Art Culture.” From The Rostrum: school yearbook: “Our able artist formerly attended Chillicothe High School, and entered our ranks in 1911. We were indeed very fortunate to have him with us, for his skill in art and valuable suggestions have aided us materially in making this book a success. He has always been recognized as a diligent and thoughtful student, and we are proud to claim him. We find him a very considerate and ever willing fellow, who has never failed us when called upon.”

-Its unknown where and in what capacity Hellmuth worked during this period. One idea, subject to research, was that he was employed at one of the many potteries in Cincinnati. Known as “the cradle of American art pottery”, a good friend of the artist, Albert F. Pons, (1888-1971) had worked in the city as an artist for Rookwood Pottery from 1904 through 1911, and was best man at Hellmuth’s 1926 wedding.

1917: Registers for WWI draft. His occupation is listed as a commercial lithographer, working for the Acme Litho Company at 601 W. 47th St., N.Y.C. He claims an exemption for service because of heart trouble on his June 5th registration card, describing himself with grey eyes, brown hair, 6′ tall and of medium build.

1918: He becomes a member of The Society of Independent Artists: exhibiting several works in the 2nd annual exhibition. His home address listed as 331 W. 55th St., NYC. Two works displayed: #919: Still Life & #920: Morning Shadows.

1920-25: Becomes a member of the Pictorial Photographers of America, exhibiting in their annual salons.

– Home address is 338 W. 22nd St., NYC.

1921: Exhibits photograph #62 “Study”at Art Center in NYC.

1922: In February, he wins first and second prizes in Class C for a contest sponsored by Kodakery: A Journal for Amateur Photographers for their contest which closed Dec. 1, 1921.

– His photograph, “A Summer Idyll” awarded honorable mention and exhibited at the Worcester, (MA) Art Museum from May 14 – June 11 as part of an exhibition of prize-winning prints organized by the journal American Photography for their second annual contest and brought to Worcester by the Worcester Camera Club.

1926: Marriage on May 8th to Alice K. Foote (1896-1989) after having moved to 79 Beverly St. in Rochester, in upstate, N.Y. Occupation on license listed as artist. His best man was Albert F. Pons of Cleveland. Pons, 1888-1971, who had been an artist for Rookwood Pottery in Cincinatti from 1904 through 1911.

1928: Now living in Cleveland, Ohio as listed in The Art Digest for Mid-May. He may have accepted a job at Morgan Lithograph Corp., a company that bought Acme Litho. (see 1940)

– A son, Joseph Foote Hellmuth, born March 1.

1930: U.S. Census lists him as a lithographic artist living at 1350 W. 102nd St., Cleveland, OH.

1940: Registers for WWII draft. He continues to be a commercial lithographer, working for Morgan Lithograph Corp. located at E. 17th and Payne Ave. in Cleveland. His home address is 1350 W. 102nd St., Cleveland, OH.

– Listed occupation on U.S. Census is poster artist for a Lithographic Company.

1945: Passes away on February 8th in Cleveland at 58 years of age.