Although long forgotten, amateur photographer John E. Dumont (1856-1944) figures prominently in the early years of American pictorial photography. However, a professional and better known acquaintance of his may change our understanding after my discovery of a small label on the back of a Dumont print made its’ way into the archive.

Left: “Hard Luck”, showing a monk playing a losing hand of cards, was most likely taken by John E. Dumont in 1890. Shown here as the cover illustration of Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper for Feb. 7, 1891, it is reproduced as a wood engraving from the original photograph, and earned Dumont a second place award and $100.00 in Leslie’s Amateur Photographic Contest which closed in January, 1891. Dumont went on to copyright “Hard Luck” in 1892. (original from Pennsylvania State University) Right: Halftone portrait of photographer John E. Dumont of Rochester, New York by unknown photographer. 6.3 x 4.7 cm. Reproduced as part of a series of portraits of “Prominent Amateur Photographers” in the Nov., 1893 issue of the American Amateur Photographer journal. (p. 513) : from: PhotoSeed Archive

Established in business beginning in 1881 in Rochester, New York as a wholesale merchandise and grocery broker specializing in items like sugars, teas, and coffees, Dumont took up photography in 1884 and was soon entering and winning awards in photographic salons around the world.

Taken in 1887, photographer John E. Dumont of Rochester, New York made this series of genre portrait photographs of a gentleman he described as “an old man who used to peddle oranges around the streets and offices in this city”. Left: “A Quite Pipe”: woodcut engraved from a copyright photograph from Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper Amateur Photographic Contest: published Jan., 17, 1891. Middle: “The Old Shaver”: woodcut engraved from a copyright photograph from Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper Amateur Photographic Contest: published Jan., 24, 1891. Right: “The Toiler’s Good-Night” : woodcut engraved from a copyright photograph illustrating a poem from Leslie’s Illustrated Weekly: published Dec., 14, 1893: originals from Pennsylvania State University

Specializing in genre scenes, his photographs were published frequently, reaching a high point when his well known study of a monk playing a losing hand of cards titled Hard Luck was published as the cover illustration (converted to a wood engraving) for Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper in early 1891, the same year he won a grand diploma at the groundbreaking Vienna Salon of Photographic Art, the highest accolade awarded for the very few American entrants whose work was even accepted, including the now venerable Alfred Stieglitz, who had only come back to America from Europe the year before.

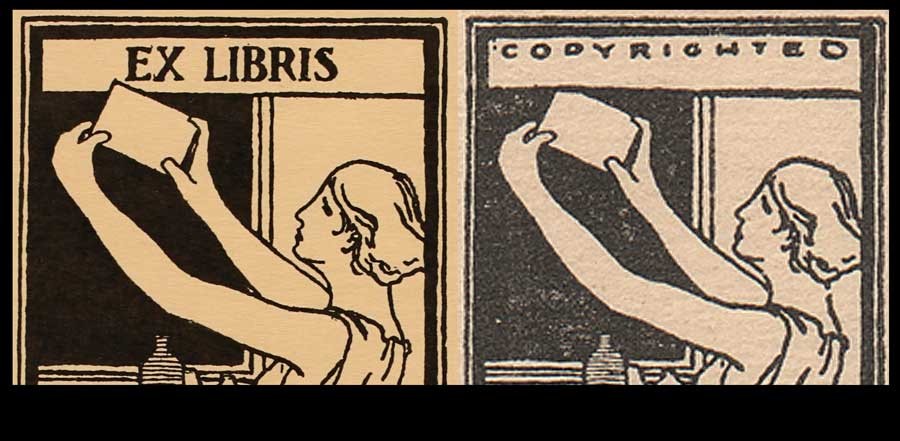

Artist: Harvey Ellis, American: 1897: medium: wood engraving: subject: copyright label for amateur American photographer John Eignas Dumont. Plate intended to represent “the genius of photography surrounded by the accessories of the “dark room.” Design: 3.4 x 1.3 cm | Label: 7.0 x 4.5 cm. Label is a variant of an ex libris bookplate Ellis designed for Dumont. from: PhotoSeed Archive

It was therefore a delightful discovery which took place for me recently after a signed Dumont carbon print of The Dice Players exhibited in the Royal Photographic Societies‘ annual salon the same year as the Vienna exhibition was acquired for the archive. But what makes it special for the confluence of art photography and evidence a new incarnation of the English Arts & Crafts movement had taken hold after arriving on American shores was a later 1897 copyright label affixed to the rear of the mounted print. A design featuring an Art-Nouveau style woodcut engraving of a woman in a darkroom holding up a glass plate, I soon discovered it was the work of noted American artist, architect and designer Harvey Ellis. (1852-1904)

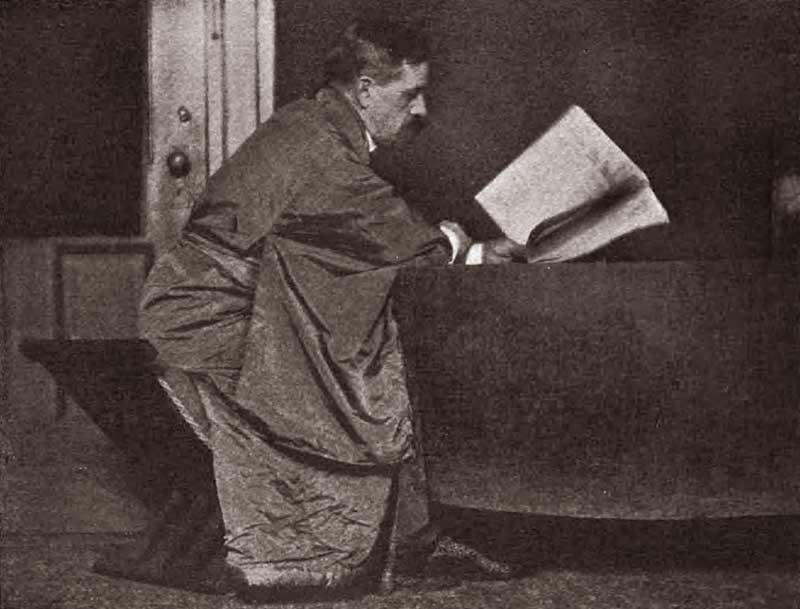

Photographic portrait of American artist, architect and designer Harvey Ellis. (1852-1904) unknown photographer: reproduced as halftone and published in the Dec., 1908 issue of The Architectural Review illustrating article on Ellis by Claude Bragdon titled Harvey Ellis: A Portrait Sketch: p. 173. Original from The University of Michigan

Never heard of him? Today, Ellis seems only to be remembered for the brief work he did in the last months of his life in 1903 for among other things, designing mission-style furniture and interior renderings of Craftsman homes in the Syracuse, New York-based architecture department for his American employer, Gustav Stickley, (1858-1942) the leader of the nascent American Arts and Crafts movement. But this is far from a full portrait of Ellis. A contemporary- architect, author, and theater designer Claude Bragdon– (1866-1946) gave a fuller account of Harvey Ellis in a posthumous outline for the December, 1908 issue of The Architectural Review. A few excerpts:

HARVEY ELLIS was a genius. This is a statement which may excite only incredulity in the minds of the many who never heard his name or knew him only by his published drawings, but it will have the instant concurrence of the few who knew well the man himself. There is the genius which achieves, and the genius which inspires others to achievement. Had it not been for the evil fairy (alcohol-editor) which presided at his birth and ruled his destiny, Harvey Ellis might have been numbered among the former; that is, he might have been a prominent, instead of an obscure, figure in that aesthetic awakening of America, now going on, of which he was among the pioneers; but even so he exercised an influence more potent than some whose names are better remembered. (p. 173)

Although many designs by Harvey Ellis were never realized in the physical form, there are notable exceptions. The Compton Hill Water Tower in Reservoir Park, St. Louis, MO, is one landmark still standing. Topping out at 179 feet, (55 m) the structure was designed by Ellis in 1896 or 97 while employed by the St. Louis architectural firm of George R. Mann and Edmond J. Eckel, and built in 1898 in the French Romanesque style of rusticated limestone and buff brick and finished in terra cotta. The tower was decommissioned in 1929 and placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1972. Photographer: Leo Kraft, American: ca. 1915: gelatin silver prints pasted in album: left: 12.1 x 6.9 cm | right: 9.8 x 6.3 cm : support: 17.6 x 25.2 cm. from: PhotoSeed Archive

… “There’s one type of mind,” Harvey remarked, “which would discover a symbol of the Trinity in three angles of a rail fence; and another which would criticize the detail of the Great White Throne itself.” Symmetry (the love of which is a sure index of the Classic mind) was his particular abhorrence. “Not symmetry, but balance,” he used to say. (p. 175)

Transient, and an unconventional architect and designer for his day, Ellis moved about the country working for firms in Minneapolis and St. Louis before returning to his native Rochester in 1893. It was sometime after this period that he most likely encountered and made the friendship of Dumont. In 1897, both became founding members of the Rochester Arts and Crafts Society, with Ellis serving as first president. That year, Dumont commissioned Ellis to design an ex libris book plate for him which was reworked slightly and reduced in size for use as a photographic copyright label-an example of which I found affixed to the verso of The Dice Players.

Details: Harvey Ellis: 1897: wood engraving: Ex Libris bookplate and Copyright label for American amateur photographer John Eignas Dumont : Left: bookplate: 9.4 x 4.1 cm: Jensen Tusch Collection- Frederikshavn Kunstmuseum & Exlibrissamling- Denmark: Right: copyright label: 3.4 x 1.3 cm | 7.0 x 4.5 cm : from: PhotoSeed Archive

In 1899, the original bookplate was described in the pages of the London Journal of the Ex Libris Society:

DUMONT BOOK-PLATES.

By the kindness of a member we are enabled to give an illustration of the book-plate of Mr. John E. Dumont, of Rochester, N.Y., designed by Mr. Harvey Ellis, of the same city. Mr. Dumont is a leading photographer in America, and his works are well known in England. The plate represents the genius of photography surrounded by the accessories of the “dark room.” Mr. Ellis, the designer, is a prominent architect and a water-colour artist of repute. The plate, here given, is graceful in design and execution. (p. 128)

The friendship between Dumont and Ellis extended to 1903. Now serving as president of the Rochester Camera Club, (founded 1889) Dumont was joined by Ellis and future American Photo-Secession member and club member Albert Boursalt while acting as judges for the club’s inaugural photographic exhibition in the newly erected Eastman Building on the campus of the Mechanics Institute. (which became RIT) From March 30 to April 11, over 200 framed photographs were displayed in a building made possible by Rochester philanthropist and Kodak head George Eastman. An account of the exhibition was published, along with the role of Ellis as judge, in the May, 1903 issue of the American Amateur Photographer. An excerpt:

It is stated by Mr. Dumont, who is most familiar with all of the photographic exhibits ever held here, that this of the Rochester Camera Club is by far the best, largest and most meritorious of any ever held in Rochester. Harvey Ellis, whose ability as an art critic is recognized by all, says that there are just as good pictures shown by the local exhibitions as any from out of the city, and that more than one half of the pictures hung are as good as those shown in any of the salons in the country, not excepting New York and Philadelphia, which rank among the highest in merit. (pp. 223-24)

Detail: “The Dice Players”: 1891: print ca. 1897 or later: John E. Dumont: carbon print: 29.2 x 25.1 cm (flush mounted to board) : This classic genre photograph by Dumont showing a group of men playing dice (possibly the con game “chuck-a-luck”) was first shown in the annual exhibition of the Royal Photographic Society in 1891 and further earned him a gold medal in another contest the same year sponsored by the English journal the Amateur Photographer. From: PhotoSeed Archive

But what immediately followed in the new Eastman Building from April 15-25, 1903: an “Exhibition of Art Craftsmanship“, featuring work from Gustav Stickley’s Craftsman Workshops, (1.) would turn out to be more significant in the overall advancement of the American Arts and Crafts movement compared to the photographic exhibition. A motivating factor perhaps? As it turned out, Harvey Ellis organized the Craftsman show, joining the Stickley firm a month later where he finished a remarkable career.

1. Historical Background: R.I.T. online resource accessed Nov., 2014: “In 1902 the Department of Decorative Arts and Crafts was established at Mechanics Institute under the leadership of Theodore Hanford Pond. An “Exhibition of Art Craftsmanship”, featuring the work of Gustav Stickley’s Craftsman Workshops, was presented in the Mechanics Institute’s Eastman Building, 15-25 April 1903.”