With Autumn upon us in the more seasonal regions of the United States, a remembrance, particularly if we are young, of the joys of cooling off in the lakes, ponds, and rivers of our youth.

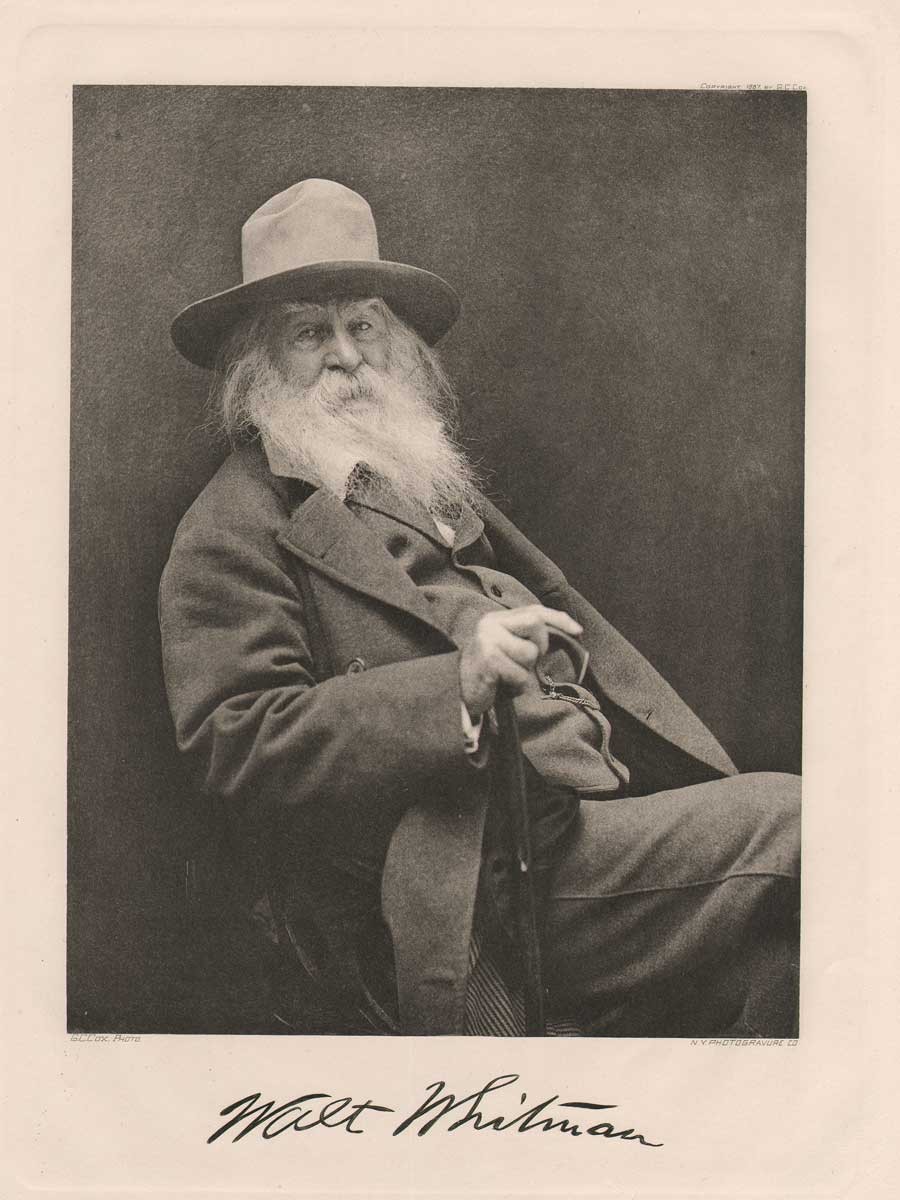

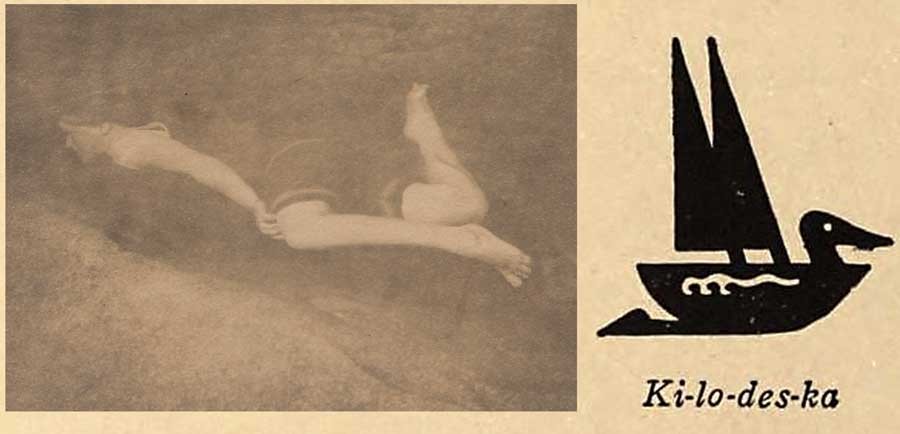

Detail: Gelatin silver print: “Mermaid Study : Ki-lo-des-ka”: ca. 1914 or before: by Charlotte Vetter Gulick: image: 7.1 x 9.2 cm: mount: 16.7 x 22.7 cm. Subject shows Katharine “Kitty” Gulick swimming underwater at Camp Wohelo in Maine. from: PhotoSeed Archive

Memories made all the more indelible if we ever had the opportunity to attend summer camp.

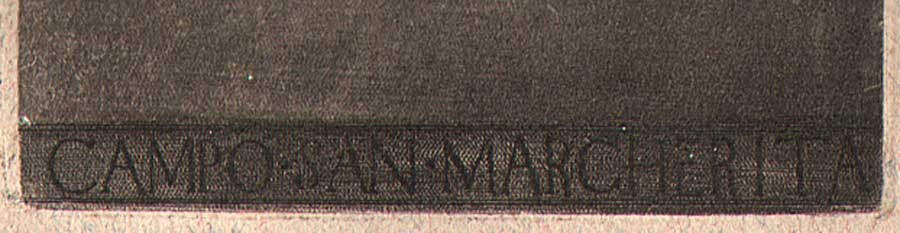

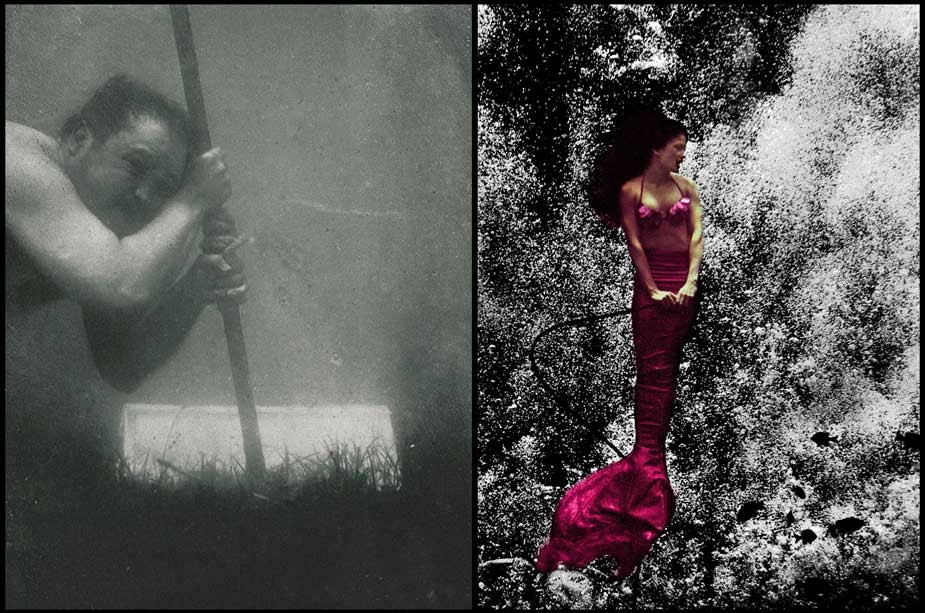

So lets go further and think about taking a photograph of someone underwater. Not a photo taken with a camera underwater, a remarkable feat in itself accomplished beginning in 1893 by the Frenchman Louis Boutan, (1.) but from the outside looking in.

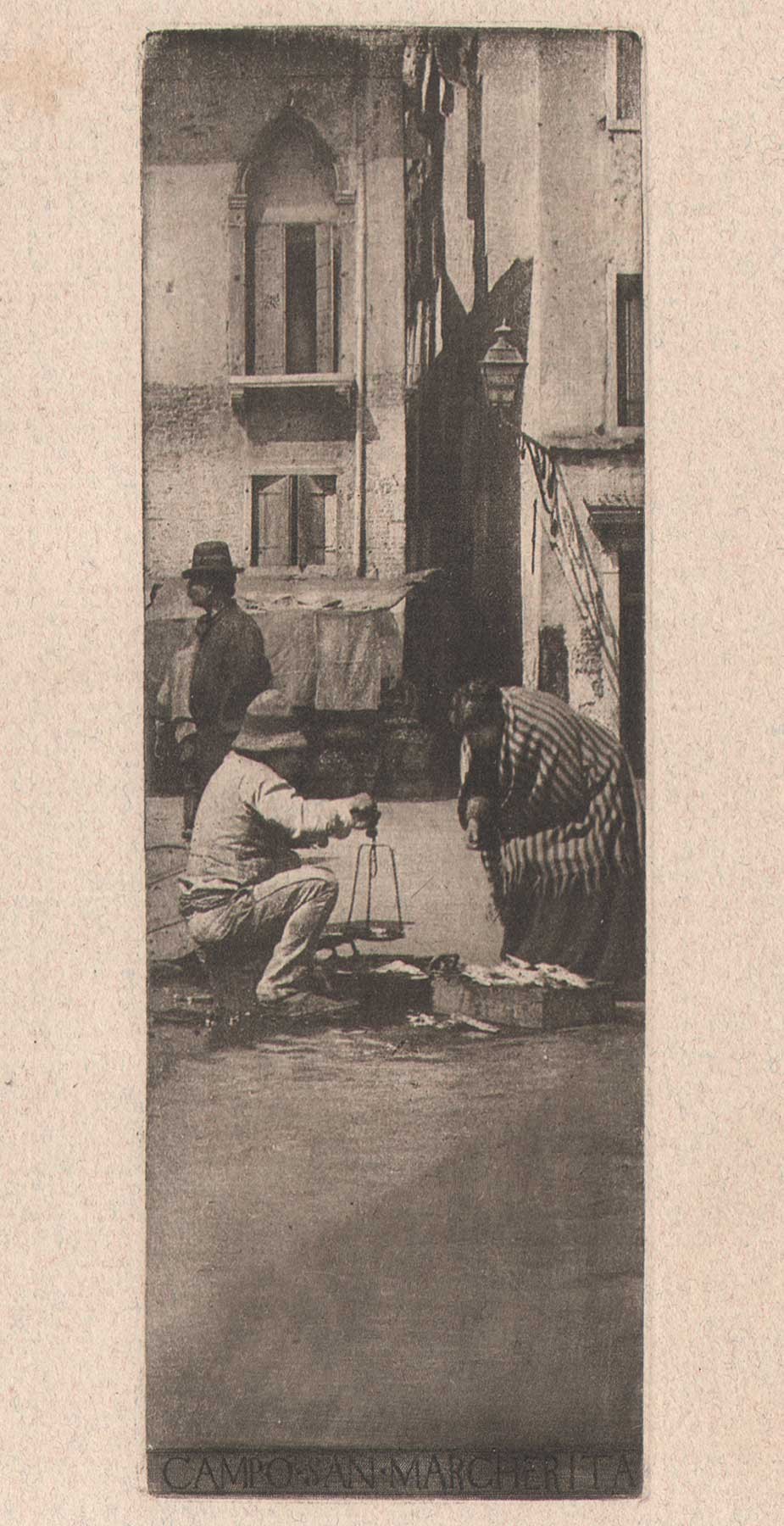

Before researching a series of photographs recently acquired for this archive showing a young woman swimming underwater, I would have thought no big deal- perhaps they were rare but could the subject matter actually be unique? After all, they were first published for a mass audience in Everybody’s Magazine in the U.S. in August of 1914, with the author exclaiming them to be “remarkable photographs…taken under conditions not easily duplicated, and have aroused great interest among artists and others who have seen the originals.” (2.)

No doubt other examples of this activity exist in the form of vintage photographs. Snapshots perhaps-but ones where actual intent existed in order to show the beauty of the human figure swimming underwater? Before or perhaps a decade or two after 1914? Somehow I doubt it.

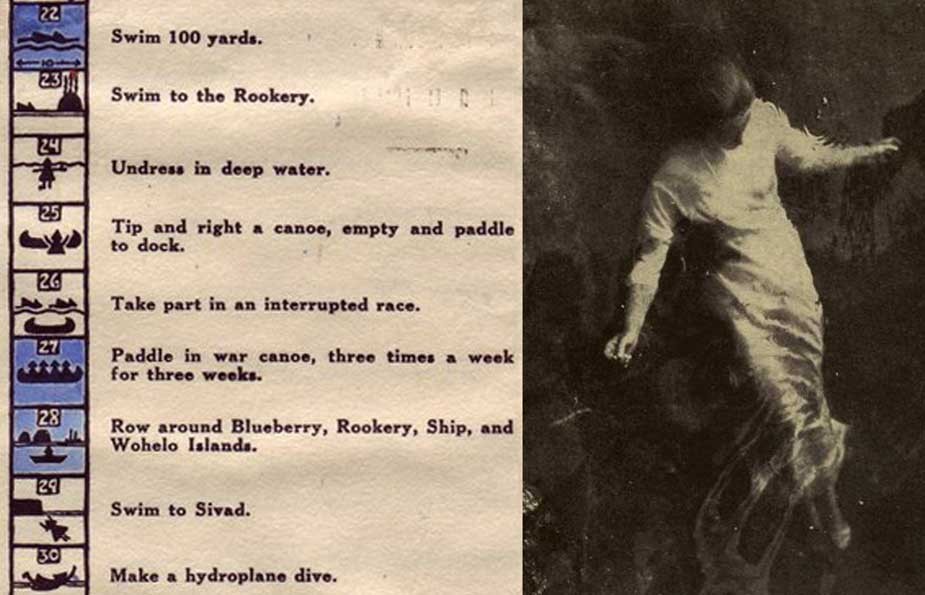

Three individual halftone and letterpress page spreads showing mermaid “Ki-lo-des-ka” (Katharine “Kitty” Gulick) swimming and lying submerged underwater: from: Everybody’s Magazine: New York: August, 1914: pp. 225-232

With a bit of research, I not only discovered the subject of the “mermaid” doing the swimming in the photos: Katharine “Kitty” Gulick, (1895-1968) but the remarkable story behind the amateur photographer who took them: her mother Charlotte Vetter Gulick. (1865-1928) Taken at Wohelo girls summer camp on the shore of Sebago Lake in Raymond, Maine, a camp founded in 1907 by Gulick and husband Luther Halsey Gulick (1865-1918) that is still going strong today, the following article from Everybody’s explains how these remarkable photos were taken and provides guiding principals behind the Camp Fire Girl movement founded by the photographer herself.

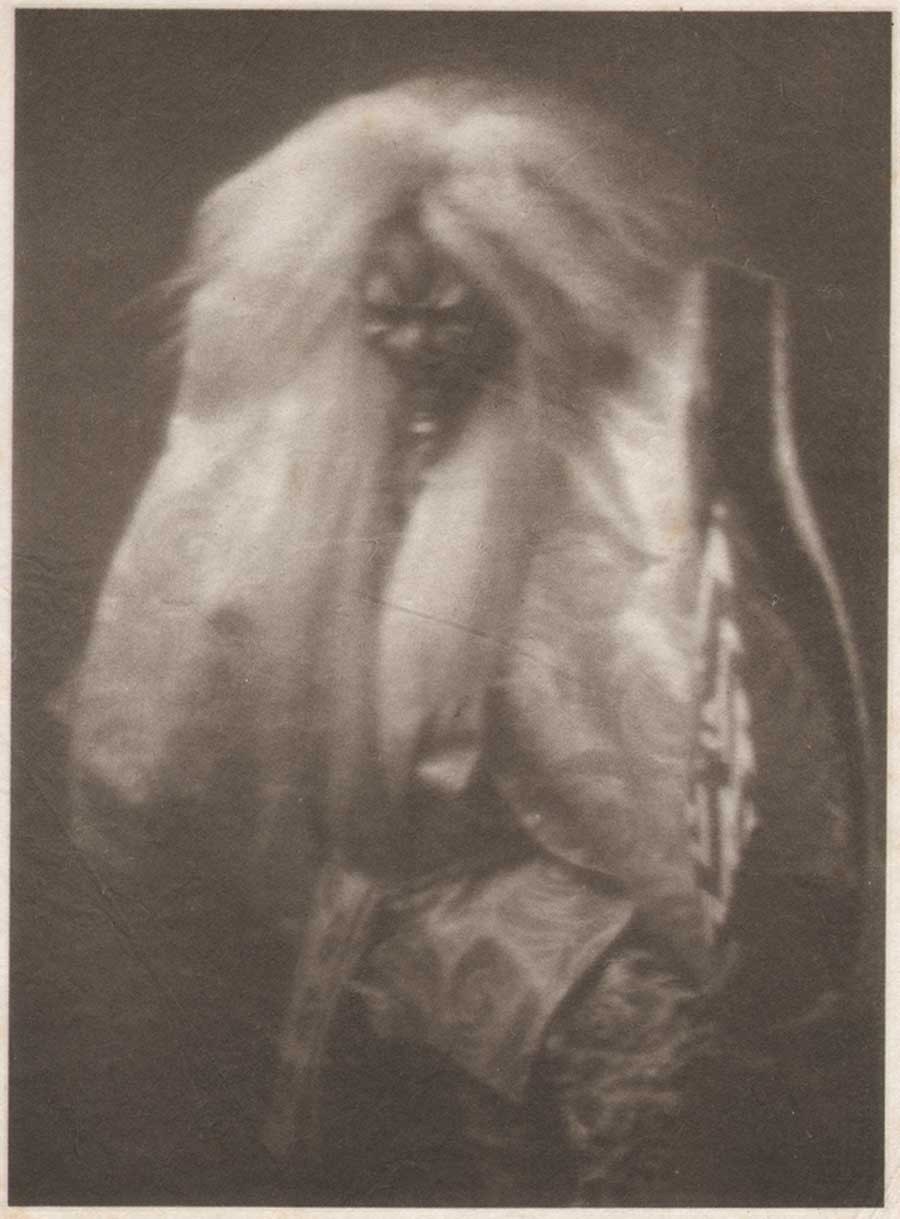

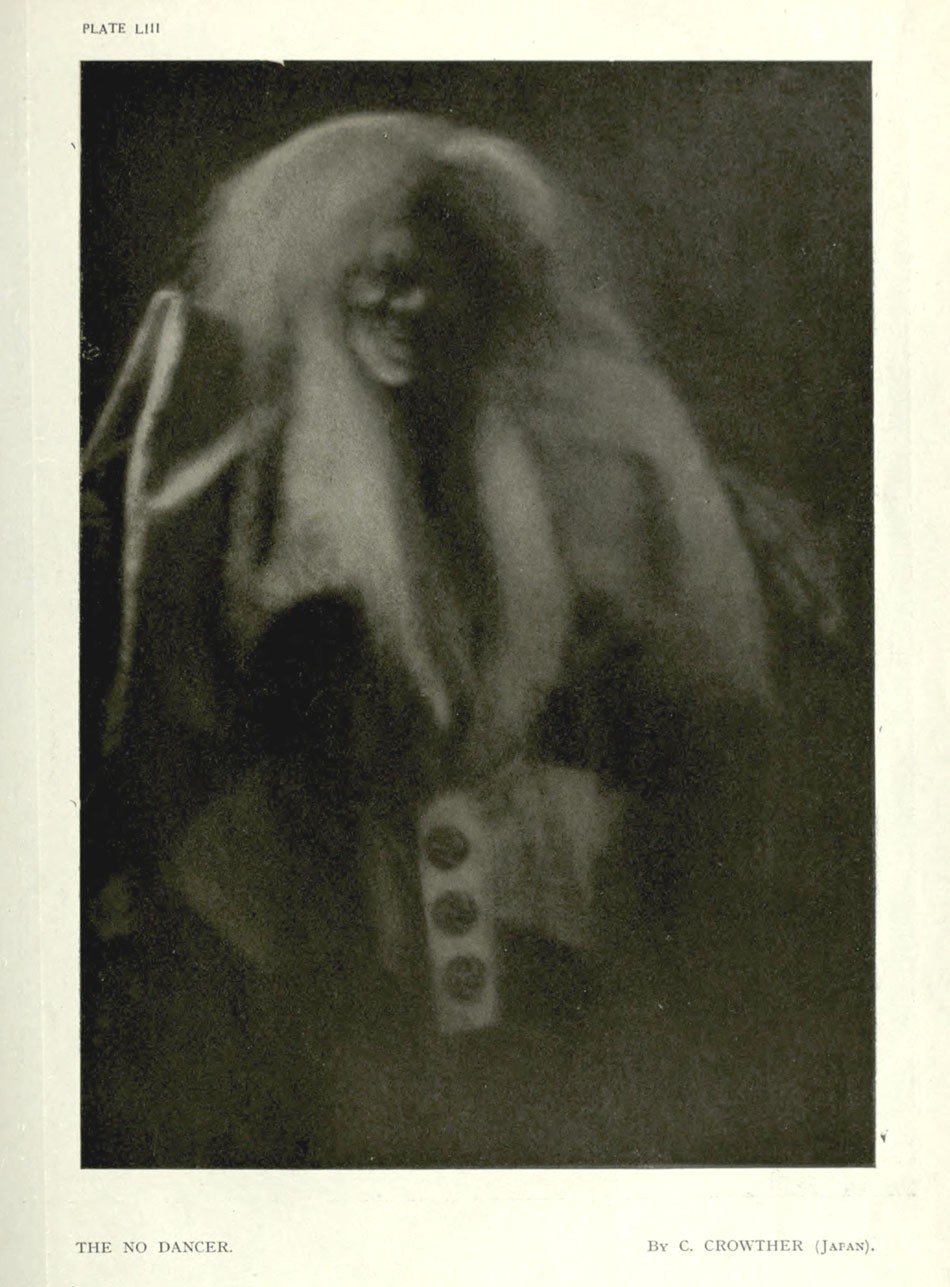

inset: detail: Gelatin silver print: “Mermaid Study : Ki-lo-des-ka” ca. 1914 or before: by Charlotte Vetter Gulick: image: 8.1 x 10.5 cm: mount: 16.8 x 23.2 cm: This was an early effort showing “Kitty” wearing a dark-colored bathing-suit “which was too nearly the tone of the rocks to give definition” before the garment was substituted for “a flowing garment of cheese-cloth” which showed up much better against the darkness of the water.: from: PhotoSeed Archive. Background: Camp Wohelo Indian symbol for “Ki-lo-des-ka” aka: “Water-bird”: from 1915 volume by Ethel Rogers: “Sebago-Wohelo Camp Fire Girls”

Illustrating the article were eight photographs of Wohelo camper “Ki-lo-des-ka“, or “Water-bird“, the aforementioned “Kitty” Gulick, with several of the originals formerly owned by her appearing with this post:

The Mermaid

A SERIES OF PHOTOGRAPHS BY MRS. LUTHER HALSEY GULICK

THESE remarkable photographs are instantaneous pictures of a young girl swimming under water. They were taken under conditions not easily duplicated, and have aroused great interest among artists and others who have seen the originals. The photographs were taken by Mrs. Luther Halsey Gulick at her private summer camp for girls on Sebago Lake, Maine. The subject was a girl who possessed the unique accomplishment of being able to swim under water as far as one hundred feet. By a long under-water swim the ripples caused by her plunge had plenty of time to die out before she passed the rock on which Mrs. Gulick stood with the camera.

The experiments were made on a brilliantly clear day. The water also was extraordinarily clear and the swimmer passed the camera’s field two or three feet below the surface. The final clue to success was found when a flowing garment of cheese-cloth was substituted for the dark-colored bathing-suit, which was too nearly the tone of the rocks to give definition. Both the figure and the draperies, under the equalizing buoyancy of the water, give a rare representation of poise, as they are entirely unaffected by the force of gravity.

How far short this description fails of conveying the art value of the photographs, their rhythm of line and beauty of form and tone, is significantly obvious; for in this margin of appeal to the imagination lies the motive that produced the pictures. They were taken at the birthplace of the Camp-Fire idea of which Mrs. Gulick is one of the chief sponsors.

Detail: Gelatin silver or Bromide print: “Mermaid Swimming” (“Ki-lo-des-ka”) ca. 1914 or before: by Charlotte Vetter Gulick: image: 8.7 x 11.2 cm: mount: 16.5 x 22.9 cm: reproduced as opening photo for article “The Mermaid” A SERIES OF PHOTOGRAPHS BY MRS. LUTHER HALSEY GULICK: in Everybody’s Magazine: New York: August, 1914: p. 225: note: hair at center of frame result of negligence from contact-printing from original negative. from: PhotoSeed Archive

The photographs are a suggestive interpretation of the first law of the Camp-Fire, “Seek beauty;” a revelation of the poetic side of one of the simple, wholesome, normal acts of life. This is the principle, full of possibilities yet undeveloped, upon which the Camp-Fire ceremonial and symbolism are based.

The first ideal of the Camp-Fire girl is the development of a well proportioned physique; a body under perfect control and responsive to every call of the spirit within. Her other ideals include an all-around training in the art of home-keeping in the modern sense, which involves a knowledge of community conditions as well as of the simple processes of home activity. This points to the further ideal of patriotism in the sense of loyalty to country, to church, to humanity, and of service in its broadest meaning.

But to hold forth these aims and say “These are the Camp-Fire” would be as inadequate as to inscribe beneath these rarely beautiful photographs the legend, “A Girl Swimming,” and consider the story told. The Camp-Fire girl makes an art of living. She finds in the mystic glow of the Camp-Fire the joy that burns at the heart of simple things, and life for her is never without beauty and romance.

Left: example of Camp Wohelo water-related challenge symbol badges from 1920 Wohelo camp yearbook: courtesy: Gulick Family. Right: detail: full-page halftone: “Ki-lo-des-ka swimming under water” : from 1915 volume by Ethel Rogers: “Sebago-Wohelo Camp Fire Girls”

A girl swimming can not always be a creature of mystic beauty, any more than speech can always be lyric or motion be always grace. But when once the beauty in a simple act has been revealed, even in a single poetic moment, a reflected glory is thrown over the commoner moments of which this is but the type. This is the poetry that the Camp-Fire girls all over America are writing into life. (3.)

Camp Fire Girls, Basket Ball and More

Born Emma L. Vetter on Dec. 12, 1865 in Oberlin, Ohio to missionary parents, (4.) Charlotte “Lottie” Gulick was educated in Kansas public schools and undertook her secondary education at Washburn College (now Washburn University) in Topeka, Kansas doing college preparatory work. She then matriculated and earned a bachelor of arts degree from Drury College in Springfield, MO. (5.) It was at Drury that she met Luther Halsey Gulick , (1865-1918) whom she married in 1887.

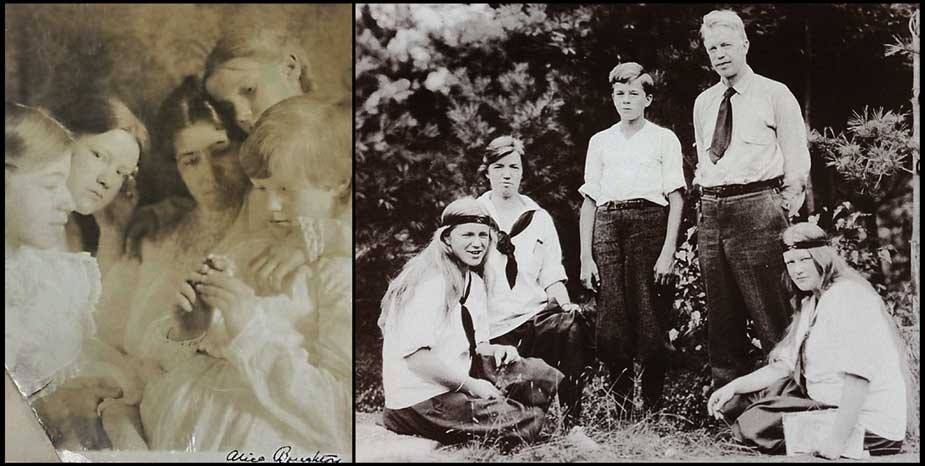

Left: photographer Charlotte Vetter Gulick is at center surrounded by her four daughters. Photograph by Alice Boughton ca. 1900. Katharine (Ki-lo-des-ka) is believed to be at right holding a flower. Reproduced later as an engraving in a New York Times article profiling the new Campfire Girls of America organization: “Girls take up the Boy Scout Idea and Band Together” (March 17, 1912) (private collection) Right: detail: members of the Gulick family from a photograph most likely taken by Charlotte Gulick around 1911. From left to right: Katharine “Kitty” Gulick (Curtis) (1895-1968); Frances “Franta” Gulick(1891-1936); Halsey Gulick; Dr. Luther Halsey Gulick (Timanous-1865-1918); Louise Gulick. (1888-1941): courtesy: Gulick Family

A strong advocate in the promotion of physical eduction as well as an organizer and author in his professional life, Dr. Luther Halsey Gulick also came from a missionary family, his father being missionary physician Luther Halsey Gulick Sr. (1828–1891) Receiving his medical degree from New York University in 1889, Dr. Gulick is perhaps best remembered today for his role in the development of the game of basketball, although this is but an interesting side story of a remarkable life. In 1891, while superintendent of the physical education department at the International YMCA Training School in Springfield, MA., (now Springfield College) he became the catalyst and inspiration for colleague James Naismith to first draw up rules for the new game of “Basket Ball”, with a peach basket nailed above the inside of a gymnasium playing court serving as the goal. His beliefs, as embodied in a poster issued after his death, were in the

“unity of body, mind and spirit, and in an education which includes all three. He devoted his life to establishing this ideal, by emphasizing the social and ethical values of physical exercise, especially through play and recreation.”

While at the YMCA, he was also responsible for designing the triangular logo which represented the YMCA philosophy of Mind, Body and Spirit. (6.)

Summer camp was an activity the Gulicks thrived on and made a lifestyle out of. Beginning in 1887, a year before their first child Louise was born, they established a camp on the shores of the Thames River in Gales Ferry CT. Co-educational, with the couples friends as well as extended Gulick family members acting as counselors to their own children and others, (7.) it operated for 20 years. In order to share what was learned to a larger audience of girls, the couple then established Camp Wohelo on Sebago Lake in 1907. An acronym comprised of the three virtues of work, health, and love, Wohelo was embodied from the start as outlined in 1915 by Charlotte Vetter Gulick:

I believe deeply and earnestly that spiritual health and development is a direct corollary of bodily vigor and control; that the joy that comes from the exercise of efficient muscles has its counterpart in the soul; that to exercise the one is to exercise the other.

Upon that rock has Wohelo been built, and its use of symbols is, perhaps, more than anything else, a working and ever-present declaration of the spiritual values inherent in all the humblest phases of our everyday life in the world. (8.)

Detail: “Mermaid Study : Submerged”: Gelatin silver print: ca. 1914 or before: by Charlotte Vetter Gulick: image: 8.4 x 10.8 cm: mount: 16.7 x 22.7 cm. : reproduced as final photo for article “The Mermaid” A SERIES OF PHOTOGRAPHS BY MRS. LUTHER HALSEY GULICK: in Everybody’s Magazine: New York: August, 1914: p. 232: from: PhotoSeed Archive

Five years before this philosophy was written, in 1910, Charlotte Gulick, known by her symbolic Indian name at the Wohelo camp as Hiiteni, which translated to “Life, more life”, came up with the idea for the Camp Fire Girls movement. An organization for girls much as the Boy Scouts of America was structured for boys, and coincidentally founded the same year, Camp Fire Girls promoted all the values she and her husband had already been teaching at their earlier camp at Gales Ferry and at Wohelo:

“The idea originated in the mind of Mrs. Gulick, and was at once indorsed by Dr. Gulick, who believes it to be logical and necessary to proper development of girls amid the changing conditions of our National life.” (9.)

Left: detail: photo by “David”: title: “Portrait Instantané D’un Plongeur” (“Instant Portrait of a Diver”) : photogravure plate XI by Paul Dujardin showing French underwater photography pioneer Louis Marie-Auguste Boutan (1859-1934) holding himself steady underwater: from: 1900 volume “La Photographie Sous-Marine et Les Progres de La Photographie” (The Progress of Underwater Photography) (between pp. 210-211) : Gallica: National Library of France online resource. Right: a modern-day mermaid: Nicole Marino plays the starring role in “The Little Mermaid” at Florida’s Weeki Wachee Springs Waterpark. In 1947, former Navy frogman Newton Perry conceived of the idea of using an air hose and perfected “hose breathing” here. Culturally, mermaids are a tourist attraction, and have entered the popular imagination through films like “The Incredible Mr. Limpet” starring Don Knotts. (1964): 1999 photo by David Spencer/The Palm Beach Post

Today, the history of the Gulick’s shared virtues of work, health and love continue on in the summer operation of their Maine camps. In a promotional 1919 silent film on Wohelo released a year before women in the United States had the Constitutional protection of the right to vote, these changing conditions of America’s National life for young women were on display. Seated in teams of coordinated paddlers in three large over-sized canoes on Lake Sebago, the ideals of resourcefulness in working together shown in the film remains an ideal for young women still valued today.

Detail: “Mermaid Sunbathing ” (“Kitty” Gulick) : Gelatin silver print: ca. 1914 or before: by Charlotte Vetter Gulick: image: 7.3 x 10.8 cm: mount: 17.0 x 22.5 cm. : In this photo, a figure study of Katharine “Kitty” Gulick by her mother, “Ki-lo-des-ka” sunbathes next to granite boulders on the Sebago Lake shoreline in Maine.: from: PhotoSeed Archive

Much like these photos of Ki-lo-des-ka the mermaid, “her yellow hair glinting golden in the sunshine” (10.) reveal beauty to us in the physical form, lines from a poem by Ralph Waldo Emerson cited by the amateur photographer Charlotte Gulick after she mastered the art of water diving at the age of 35 brings forth a desire in the human spirit to symbolically enter the depths as well:

“To vision profounder

Man’s spirit must dive.” (11.)

Notes:

1. Louis Marie-Auguste Boutan. (1859-1934) Boutan used specially-designed underwater camera housings, publishing his research conducted from 1892-1900 for a large audience in the 1900 volume “La Photographie Sous-Marine et Les Progres de La Photographie“. (The Progress of Underwater Photography)

2. from: The Mermaid: in: Everybody’s Magazine: New York: The Ridgway Company Publishers: August, 1914: p. 225

3. Ibid: pp. 225-232

4. 1870 U.S. Census. Gulick changed her name to Charlotte sometime after 1900 but was known as “Lottie”

5. Gulick background: Margaret R. and Dennis S. O’Leary: Adventures at Wohelo Camp – Summer of 1928: 2011: iUniverse: p. 24

6. 1921 poster of Luther Halsey Gulick: Makers of American Ideals poster issued by the National Child Welfare Association: Springfield College Digital online resource accessed Oct., 2014

7. background: Camp Timanous website accessed Oct., 2014. Owned by the Suitor family since the 1930’s, the camp was originally founded by Luther Halsey Gulick in 1917, whose symbolic Indian name Timanous– was “Guiding Spirit“. In the introduction to the 1915 Sebago-Wohelo Camp Fire Girls volume, Charlotte Gulick states as many as 75 people camped together at Gales Ferry before Wohelo was established.

8. excerpt: Introduction: Mrs. Luther Halsey Gulick: Ethel Rogers: Sebago-Wohelo Camp Fire Girls: Battle Creek, MI: Good Health Publishing Company: 1915: pp. 22-23

9. excerpt: Girls Take up the Boy Scout Idea and Band Together: Edward Marshall: in: The New York Times: March 17, 1912

10. Sebago-Wohelo Camp Fire Girls: p. 94

11. Ibid: p. 22

: and of course I’m happy to be corrected