Subversive and unwilling to play by the rules. This is why the body of work produced by British photographer Julia Margaret Cameron (1815–1879) should still matter to us today.

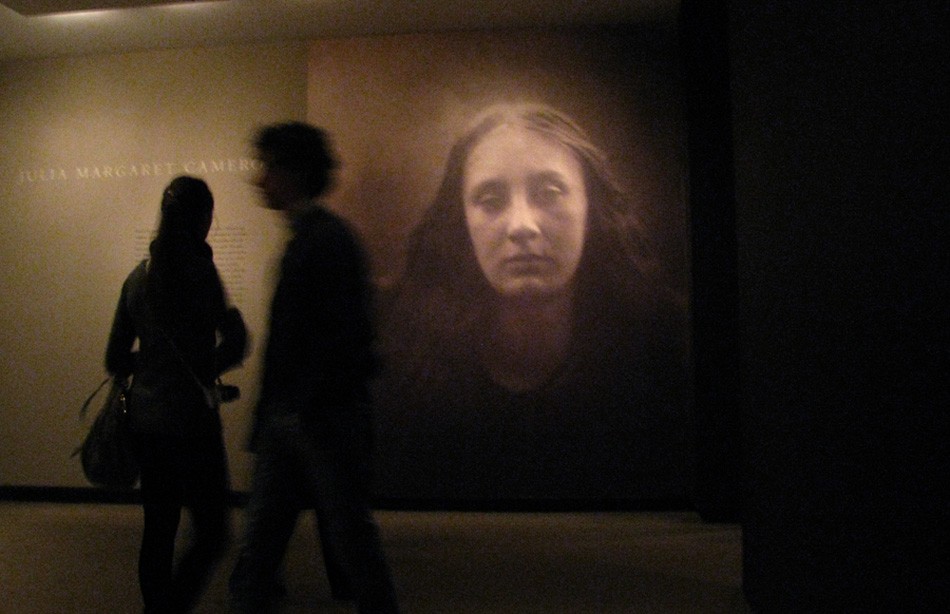

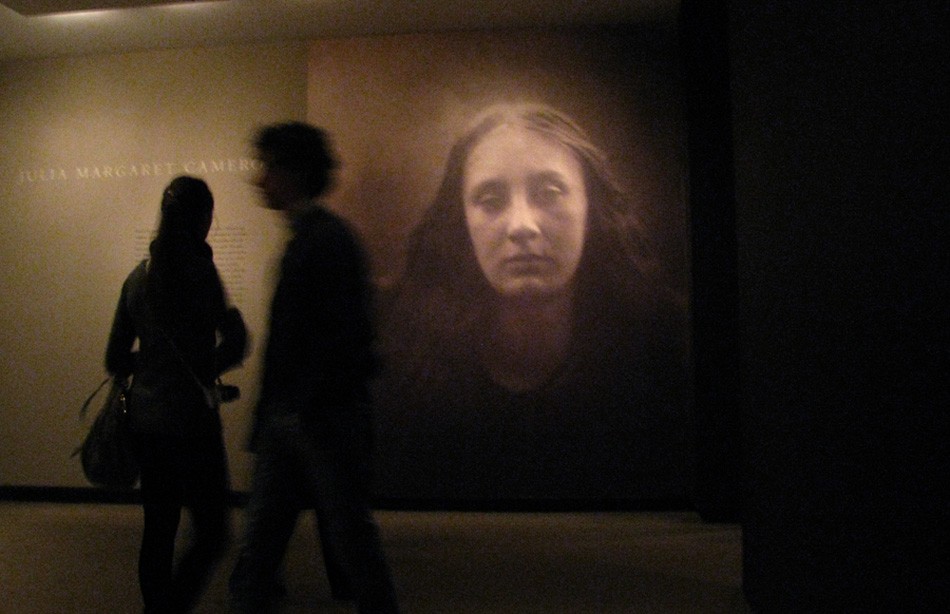

Silhouetted visitors to the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Gallery 852 in December, 2013 are seen in the entryway to the exhibit with a wall-mounted, mural-sized version of the Cameron photograph “Christabel” taken in 1866 in the background. The show was open from August 19, 2013 to January 5, 2014. PhotoSeed Archive photograph by David Spencer

How can one not admire the intent and courage it must have taken her to focus a camera lens in the era of wet plate photography (1860s-1870s) and then, just as often as not, deliberately have the mischievous bent to throw that lens slightly out of focus in order to create photographs often resembling the feelings found in dreams? Photographs that justifiably draw admiration and discussion even today of the lives of Victorian celebrities and house servants who were convinced to sit or be dragged in front of that camera.

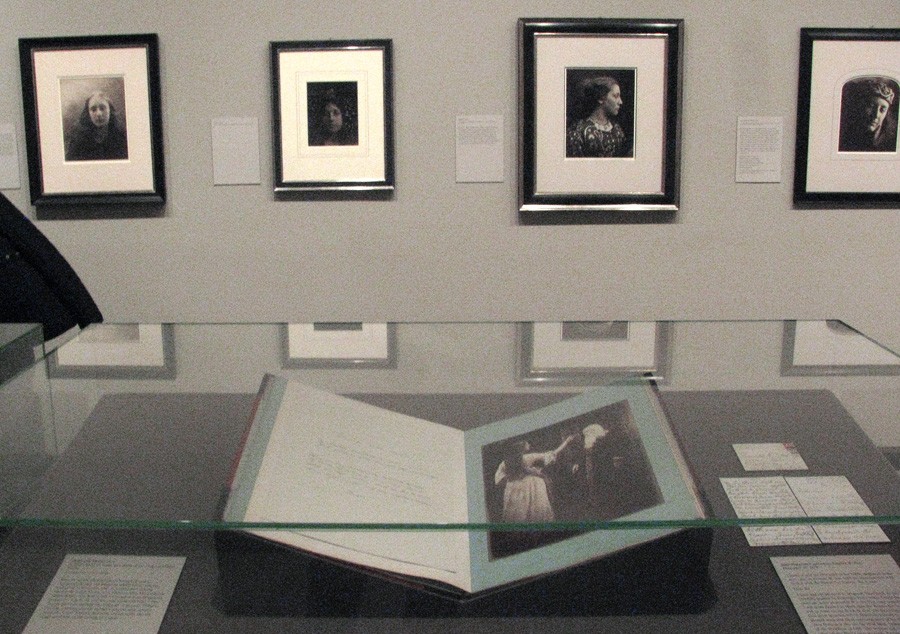

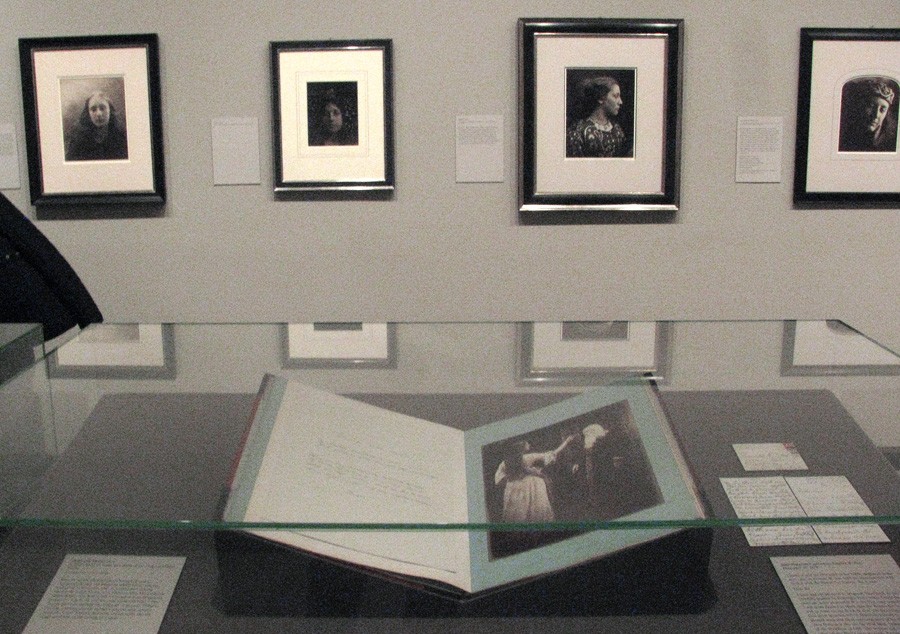

Organized by Malcolm Daniel, Senior Curator in the Department of Photographs at the Met, the tightly edited show featured 35 framed vintage works by Cameron as well as several photographs by her contemporaries. The glass display case in this installation view displayed several folio volumes of the work “Illustrations to Tennyson’s Idylls of the King, and Other Poems” published by Henry S. King in London in 1875. The work seen here at front is “Vivien and Merlin” (1874)- one 24 original photographs that appeared in the double volume folio. PhotoSeed Archive photograph by David Spencer

For those inclined to learn the mysterious ingredient-and staying power so to speak-of Cameron’s photography-the answer might be a single word: “beauty”. This might indeed be the key, a Citizen Kane, Rosebud moment if you will, the one final word she reportedly uttered on her deathbed.

Beauty, and a renewed appreciation is what I took away from a visit late last year to a show at the Metropolitan Museum of Art simply titled “Julia Margaret Cameron“.

A painting by English artist George Frederick Watts of Julia Margaret Cameron completed in 1852 is reproduced here as a large format plate photogravure included in the 1893 folio volume “Alfred, Lord Tennyson and his Friends” published in London by T. Fisher Unwin in a limited edition. image: 24.5 x 19.3 cm : laid paper cream-colored leaf: 44.3 x 36.0 cm. from: PhotoSeed Archive

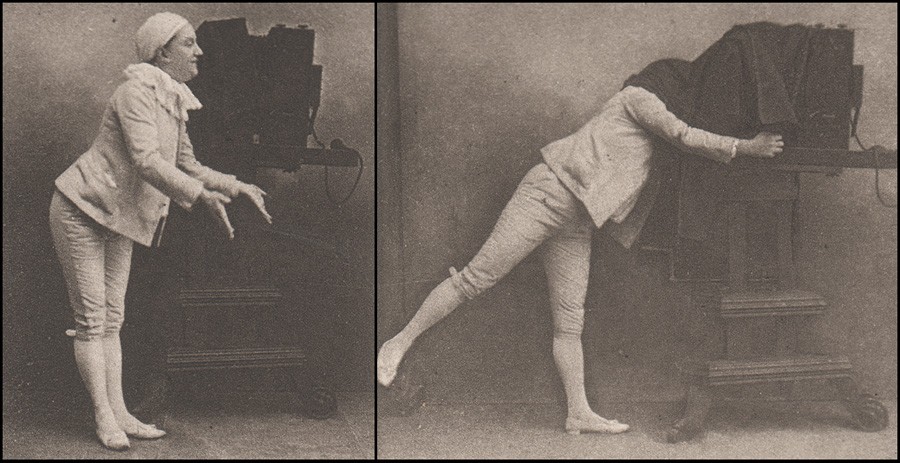

Surprisingly, it was first devoted solely to her work at the museum, a tightly edited overview comprised of 38 works, including several by her contemporaries: David Wilkie Wynfield, William Frederick Lake Price, and Oscar Gustav Rejlander.

The wall copy set the stage for those not already familiar with Cameron, describing her rightly as:

“One of the greatest portraitists in the history of photography—indeed in any medium“…

A further explanatory statement in her own words followed:

“From the first moment I handled my lens with a tender ardour,” she wrote, “and it has become to me as a living thing, with voice and memory and creative vigour.”

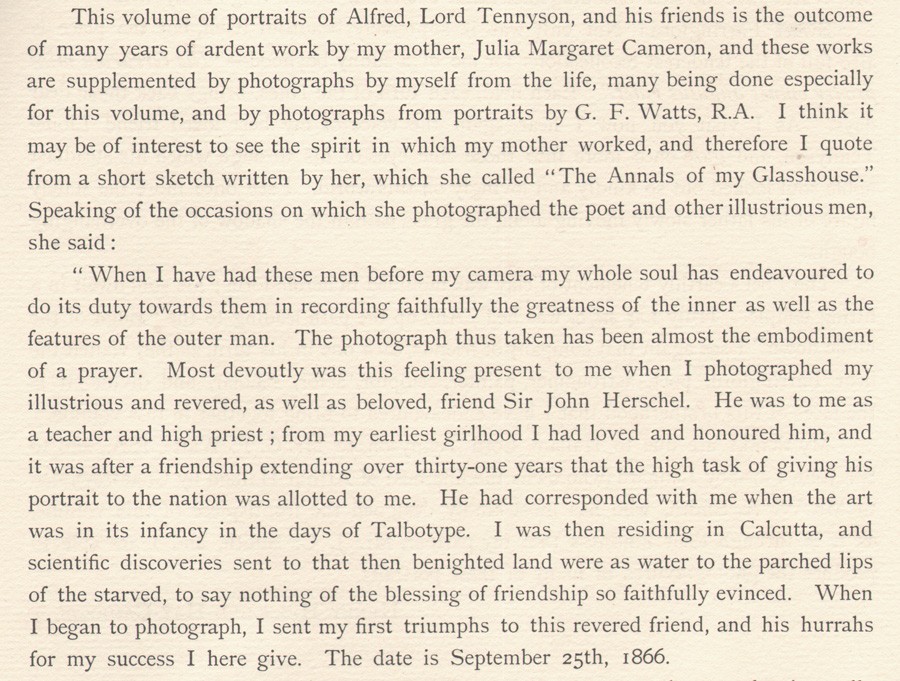

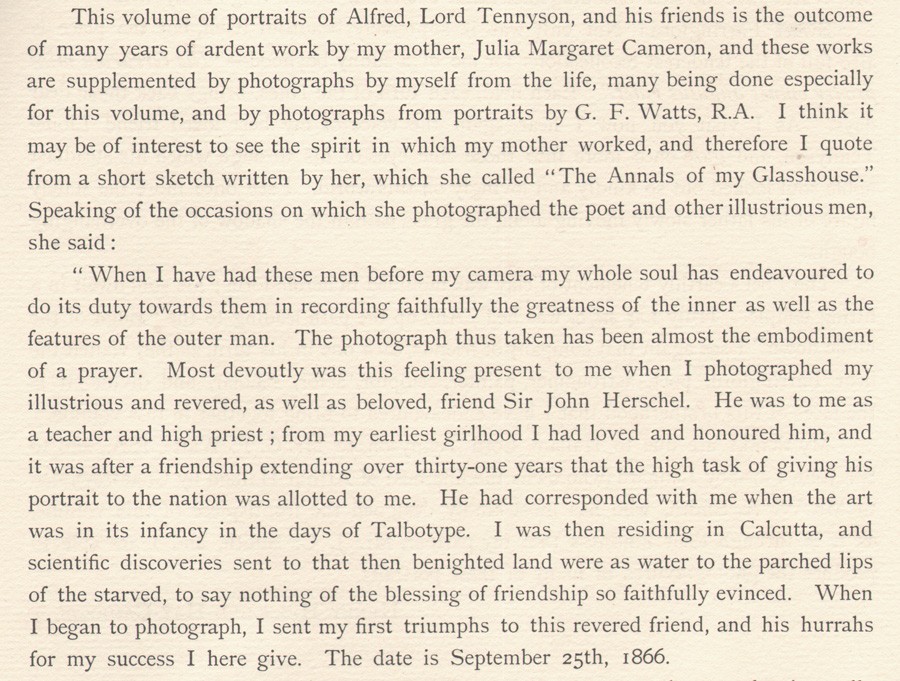

A detail from the first page of the letterpress Introduction to “Alfred, Lord Tennyson and his Friends”(1893) by Cameron’s son Henry Herschel Hay Cameron. A quote from her “Annals of my Glasshouse” states she felt the photographs taken of illustrious men were akin to being “almost the embodiment of a prayer”. from: PhotoSeed Archive

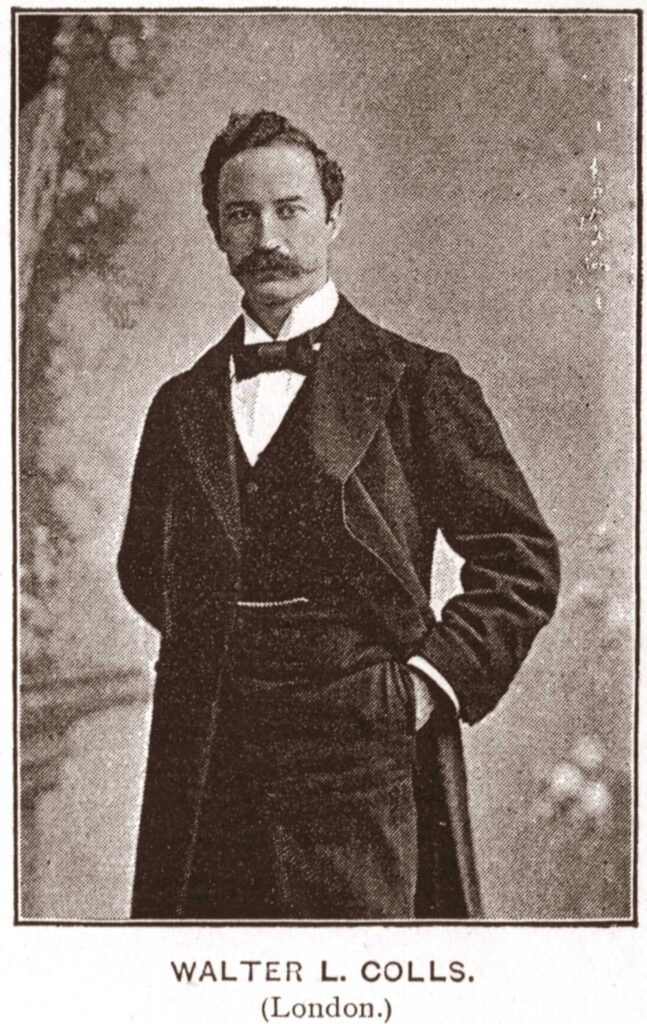

Words that no doubt have influenced scores of photographers, painters and others working in various artistic disciplines during the many decades since her passing. An important early tribute came in the lifetime of Cameron’s youngest son Henry Herschel Hay Cameron. (1852-1911) Inspired no doubt by his mother’s art, he was a working photographer who maintained a London studio, and provided the Introduction as well as a series of complimentary portraits paired with those by his mother for the folio volume Alfred, Lord Tennyson and his Friends. This series of 25 large-plate photogravures along with letterpress was published in a limited edition in 1893.

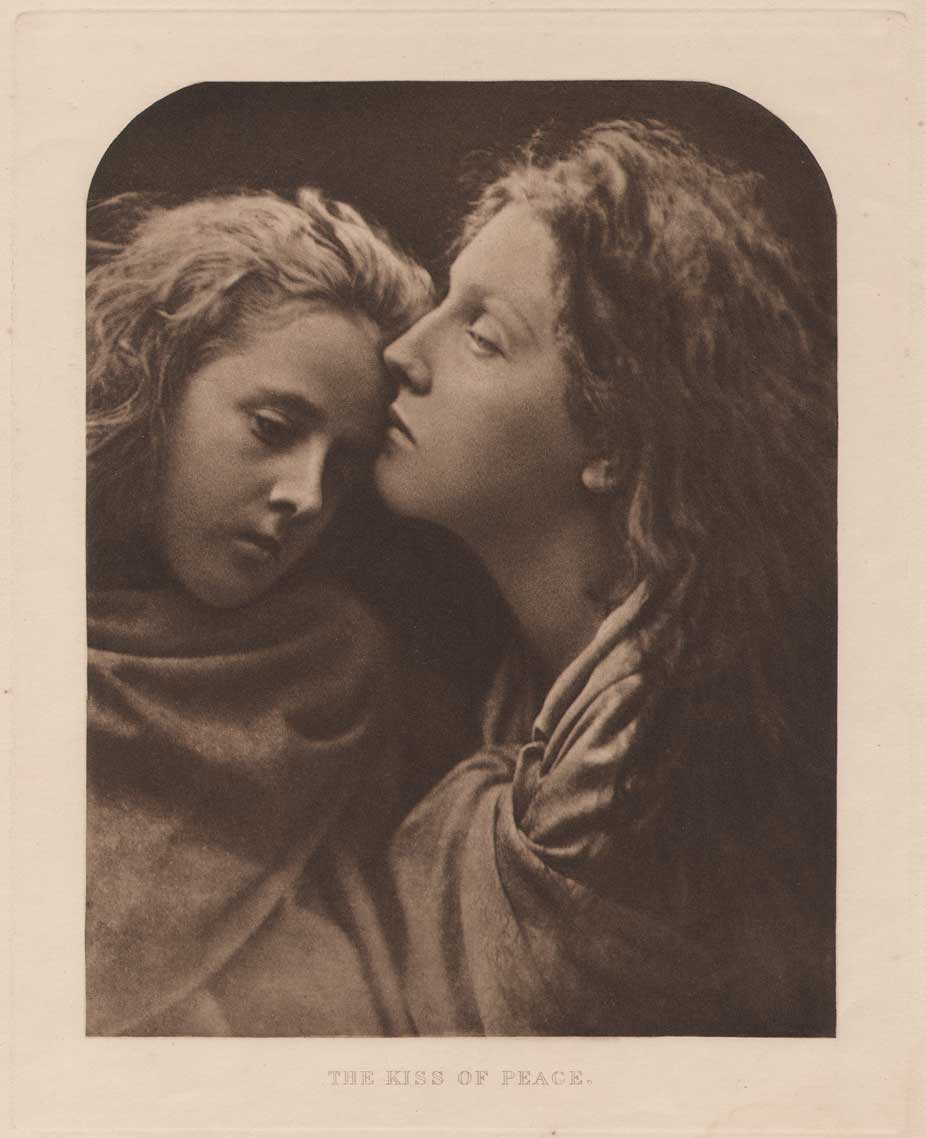

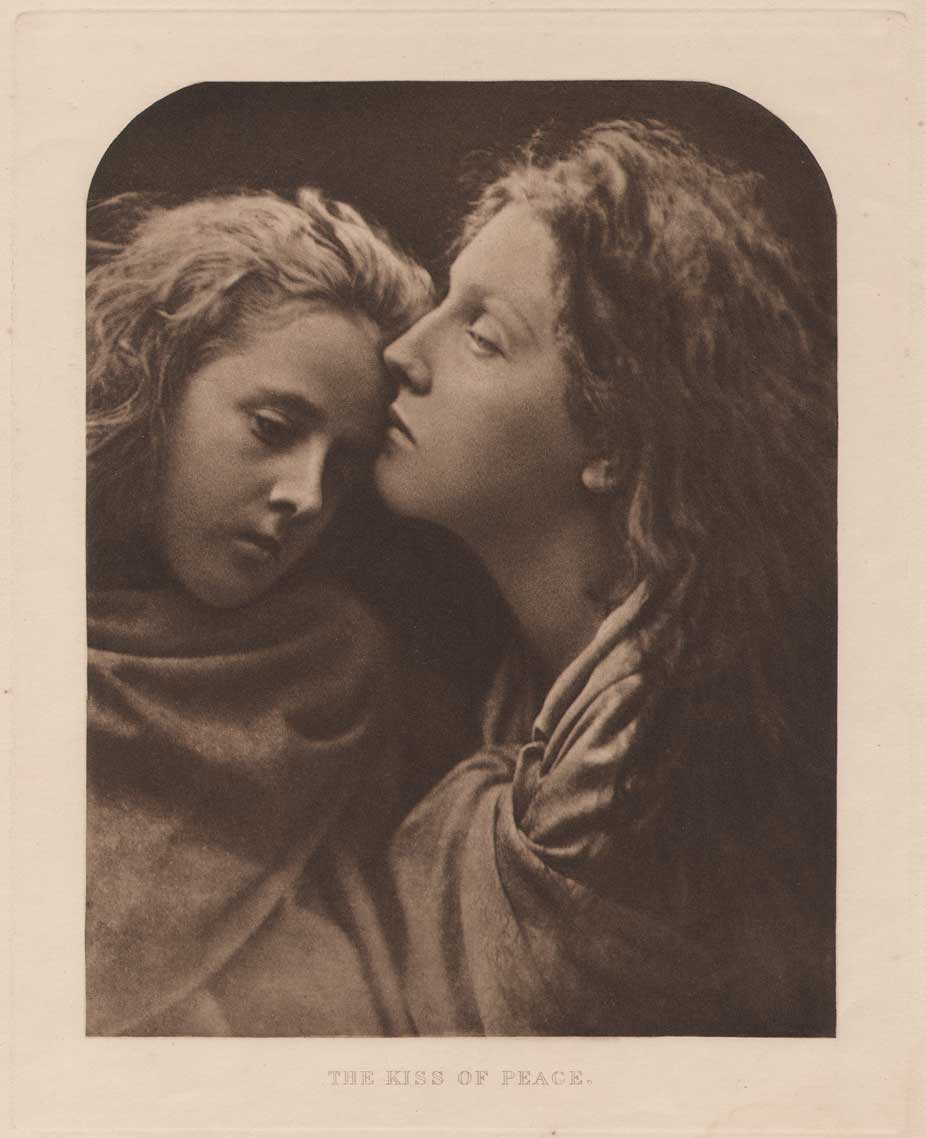

Inspired by the Biblical story of the Visitation, “The Kiss of Peace” is shown here as a large plate photogravure included with the 5th issue of the English publication “Sun Artists” published in 1890. Taken in 1869 by Cameron, it is believed to show Florence Anson at left, the daughter of Lord Litchfield, and Mary Hillier, Cameron’s personal maid. See: JMC: The Complete Photographs, cat. #1129. image: 21.8 x 17.1 cm: sheet: 38.0 x 28.4 cm: Vintage gravure from PhotoSeed Archive.

Other notable remembrances of Cameron’s work appeared earlier and much later. In 1890, the English publication Sun Artists featured four of her photographs: Sir John Herschel, Alfred Lord Tennyson and the allegorical works The Day Dream and The Kiss of Peace. All large-plate gravures for the 5th Number.

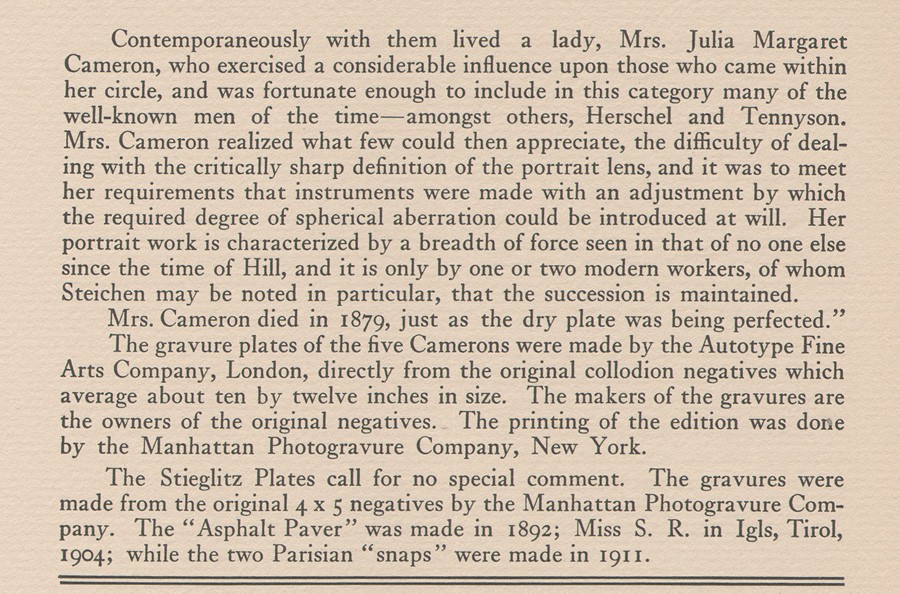

Editor Alfred Stieglitz gave background to Cameron’s work he published in Camera Work XLI, (1913) with a nod to her willingness to break rules when it came to portraiture: “Mrs. Cameron realized what few could then appreciate, the difficulty of dealing with the critically sharp definition of the portrait lens, and it was to meet her requirements that instruments were made with an adjustment by which the required degree of spherical aberration could be introduced at will.” detail: vintage letterpress page from PhotoSeed Archive.

For Camera Work 41 published in 1913, editor Alfred Stieglitz presented five plates of Cameron’s work published as tissue gravures: two of Scottish philosopher Thomas Carlyle, portraits of English polymath John Herschel and Hungarian violinist Joseph Joachim and an allegorical study of English Shakespearean actress Ellen Terry taken done in 1864 when she was 16 originally titled “Sadness“.

English Shakespearean actress Ellen Terry was included as a hand-pulled, Japanese tissue photogravure in Camera Work XLI,(1913) photographed by Cameron in 1864 when she was 16 years of age. The allegorical photograph originally carried the title of “Sadness”. entire vintage tipped plate shown on original CW mount: circular image: 15.7 cm | sheet: 28.0 x 20.1 cm | mount: 29.4 x 21.0 cm. from PhotoSeed Archive

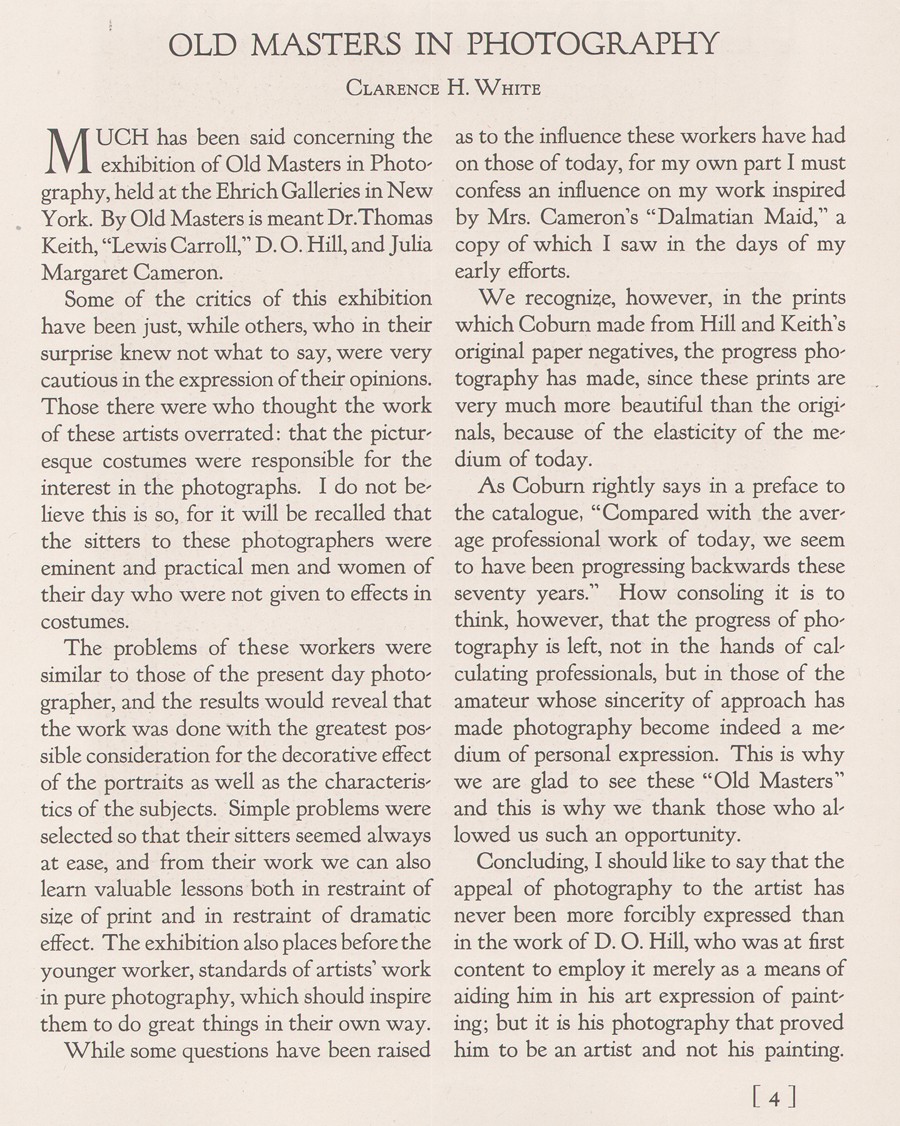

Later in the British Number of the short-lived publication Platinum Print published in Feb. 1915, American photographer Clarence White’s essay titled Old Masters in Photography lauded Cameron as an early influence, singling out her photograph he most likely saw in an 1891 issue of Sun and Shade titled the Dalmatian Maid.

Julia Margaret Cameron was one of “The Old Masters of Photography” exhibit arranged by Alvin Langdon Coburn and presented at the Ehrich Galleries of New York City in December, 1914. Author Clarence White weighs in on the exhibit, discussing the influence of Cameron on his own work. Single letterpress page from “Platinum Print”: Feb. 1915: PhotoSeed Archive

This portrait of Christina Spartali, a neighbor of Cameron on the Isle of Wight who was most certainly not a maid, as her family had made their fortune from the cotton trade and her father was Consul-General for Greece, was taken in 1868. White observed:

“While some questions have been raised as to the influence these workers have had on those of today, for my own part I must confess an influence on my work inspired by Mrs. Cameron’s “Dalmatian Maid,” a copy of which I saw in the days of my early efforts.” (p.4)

“A Dalmatian Maid”, taken in 1868, is a portrait of Christina Spartali, a neighbor to Cameron on the Isle of Wight. from: Sun & Shade: July, 1891: plate IV (whole issue #35) image: 19.3 x 12.8 cm | plate: 34.0 x 26.2 cm N.Y. Photogravure Co.: PhotoSeed Archive

Although ended, photographs from the Cameron show at the Met can still be viewed in digital form, along with an ambitious project devoted to her and other notable photographers now ongoing on behalf of the rich photographic collection held by the Royal Photographic Society at the National Media Museum in Bradford, England.

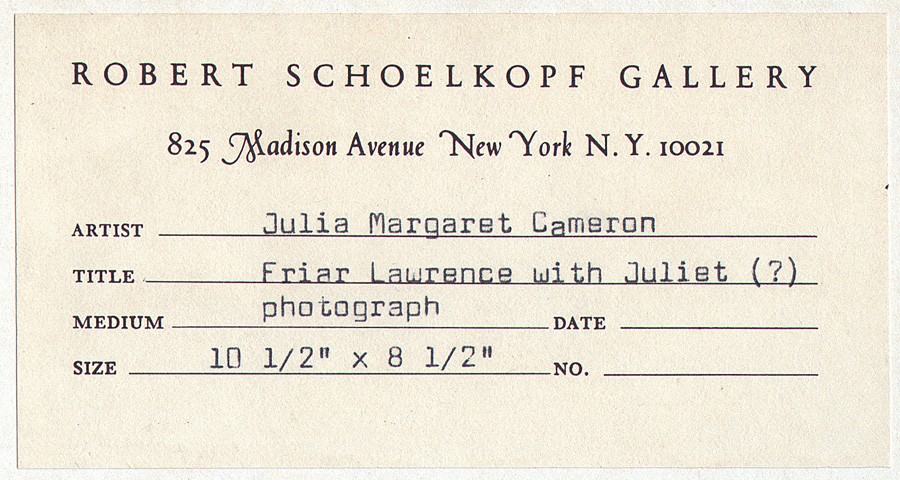

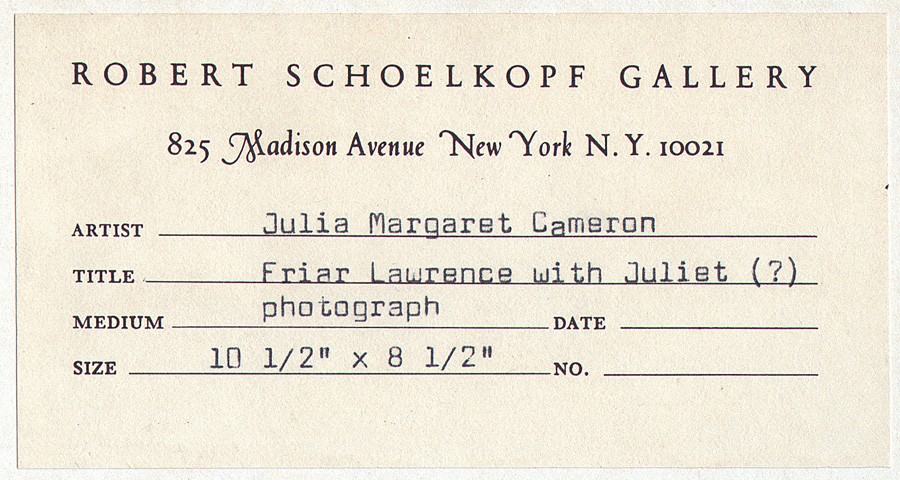

Robert Schoelkopf Gallery paper adhesive label from ca. 1965-1972 affixed to verso of mount from photograph “Friar Laurence and Juliet” : 5.8 x 11.1 cm. Formerly located at 825 Madison Ave. in New York City, the Schoelkopf gallery was established in 1962 and closed in 1991. It was one of the very first in the United States to present photography as a fine art and by the Spring of 1974, had “opened a gallery dedicated to photography on the second floor” of this address. from: PhotoSeed Archive

Other treasures await additional scholarship. For our part, PhotoSeed presents with this post a seldom-seen work by Cameron formerly owned by Peter Hukill, (1927-2003) an early collector of fine art photography who built a collection thanks to the early efforts of galleries including the former Robert Schoelkopf Gallery in New York City, the records of which now reside in the Smithsonian Archives of American Art.

“Friar Laurence and Juliet”, by Julia Margaret Cameron: copyrighted Nov. 11, 1865. Three separate versions of this title exist as recorded in Julia Margaret Cameron: The Complete Photographs. (Cox & Ford) This version with model Mary Hillier- Cameron’s personal maid- wearing lighter-colored topcoat posing with Henry Taylor. (C&F #1089) Vintage albumen silver print mounted separately on board presented within window of modern mount. Condition of print exhibits uneven arched top with free-hand drawn ink line near top margin and surface marks to print emulsion. image: 28.2 x 28.6 cm | mount: 60.7 x 50.7 cm. photograph placed at auction by Robert Schoelkopf Gallery in 1972 (Parke-Bernet) and acquired by Peter Hukill. from: PhotoSeed Archive

Prescient, and subversive indeed. The Schoelkopf Gallery was apparently one of the first to feature photography as fine art in the United States. In 1967, it had the distinction of mounting the last solo show of Cameron’s work before the Met’s which opened in 2013: “timing it to coincide with a show at the Metropolitan Museum of Art that focused on Cameron as one of four Victorian photographers.” (1.)

1. excerpt: Robert Schoelkopf Gallery records, 1851-1991: Smithsonian Archives of American Art online resource: “In its early years the Robert Schoelkopf Gallery contributed considerably to the development of interest in fine art photography that fostered an increasingly lucrative market for photographic prints during the 1960s and 1970s.”