An objective reviewer I am not when it comes to photographers considered major figures in the emerging artistic aesthetic movement from the beginning of the 20th century.

While a lampost banner with the Heinrich Kühn photograph “Study in Tonal Values III, (Mary Warner)” taken in 1908 is displayed along East 86th Street near the New York City museum Neue Galerie for the show “Heinrich Kuehn and his American Circle: Alfred Stieglitz and Edward Steichen”, the evolving tableau of life on the street below provides for a continual source of photographic delights. PhotoSeed Archive photograph by David Spencer

Instead, shameless promoter would perhaps better describe my enthusiasm for Austrian Heinrich Kühn, (1866-1944) the subject of a museum exhibition now taking place in New York City. And with that, I heartily recommend a visit to:

Heinrich Kuehn and his American Circle: Alfred Stieglitz and Edward Steichen

now on view at the Neue Galerie through August 27th.

Originally finished in 1914 for the industrialist William Starr Miller II at 1048 Fifth Avenue by the architectural firm Carrère & Hastings, (responsible for the design of the New York Public Library) the Neue Galerie was first opened to the public in 2001 and specializes in German and Austrian art and design. PhotoSeed Archive photograph by David Spencer

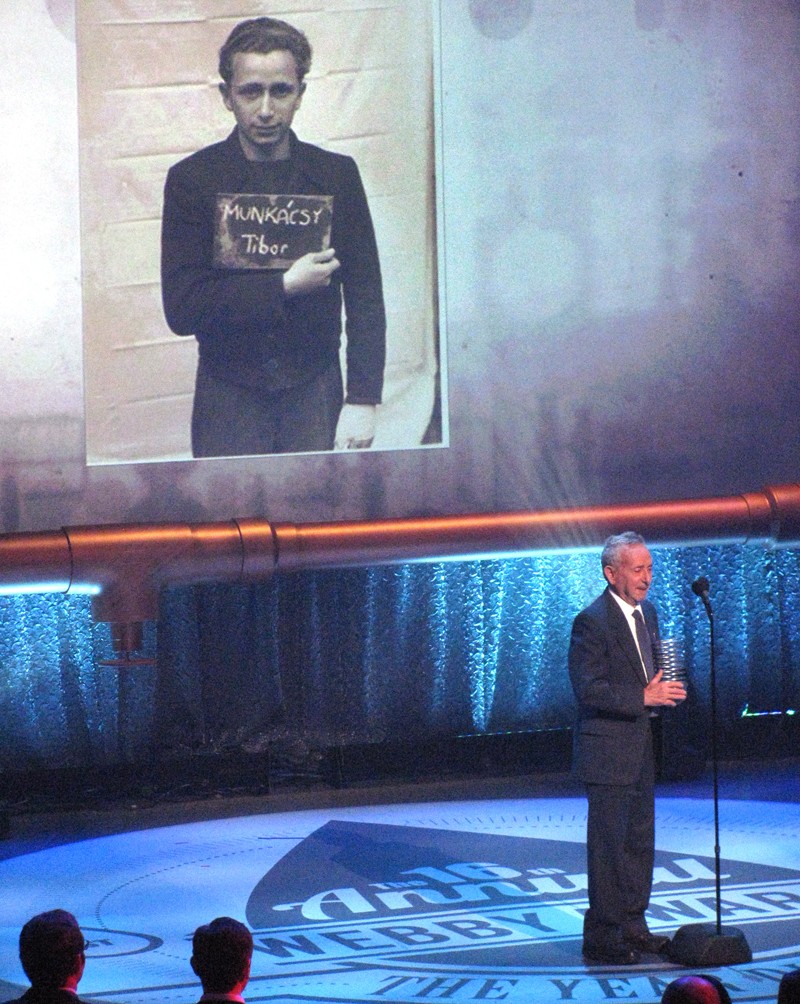

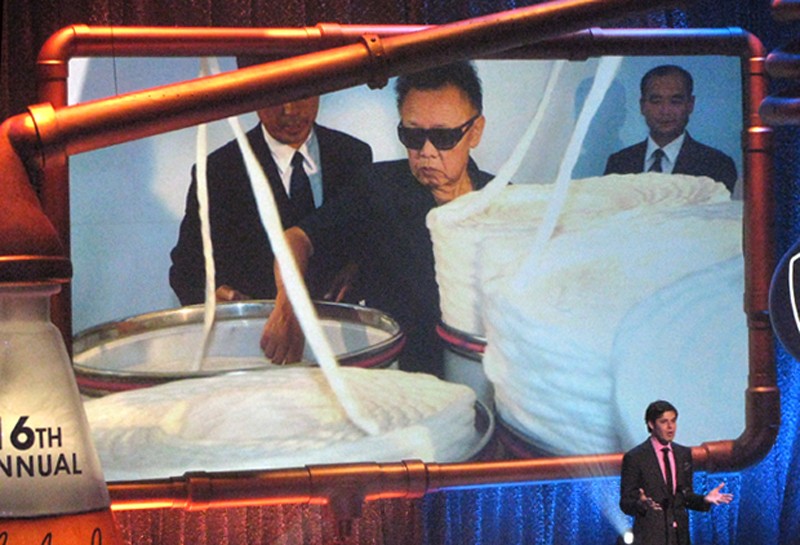

It was exhilarating to be back in New York so soon after my attendance at the Webby awards, but this was a working trip for PhotoSeed, with the first half of the day spent uptown at the Neue Galerie and the rest spent downtown working on an upcoming post on the history of The Photographic Times.

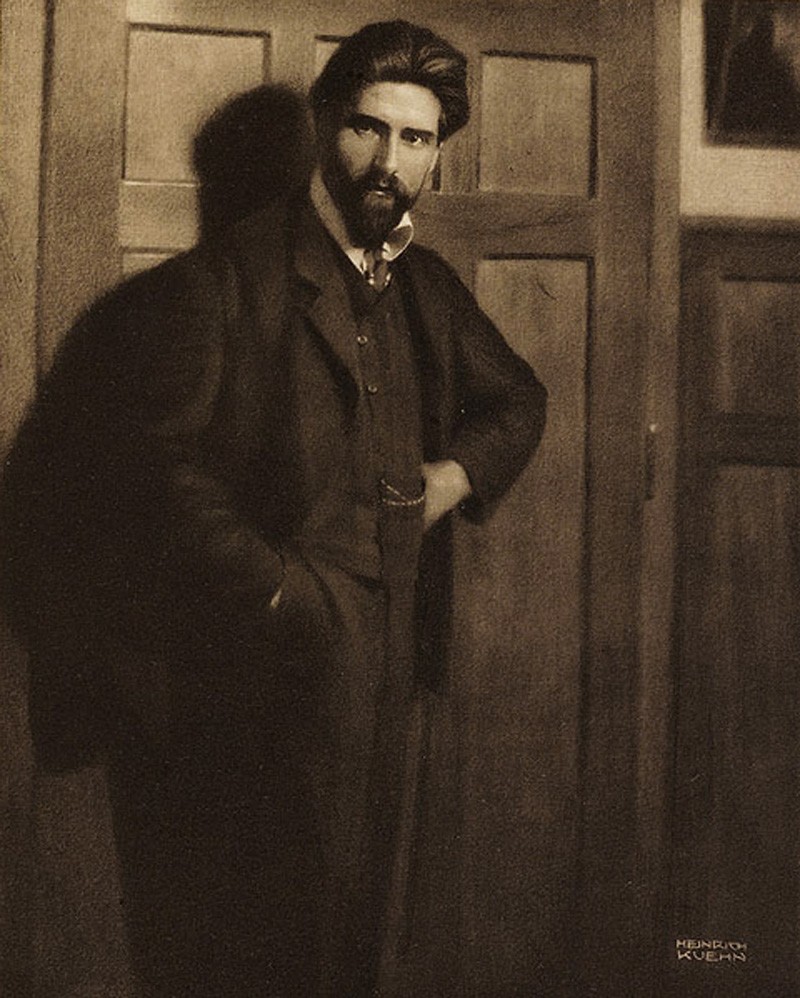

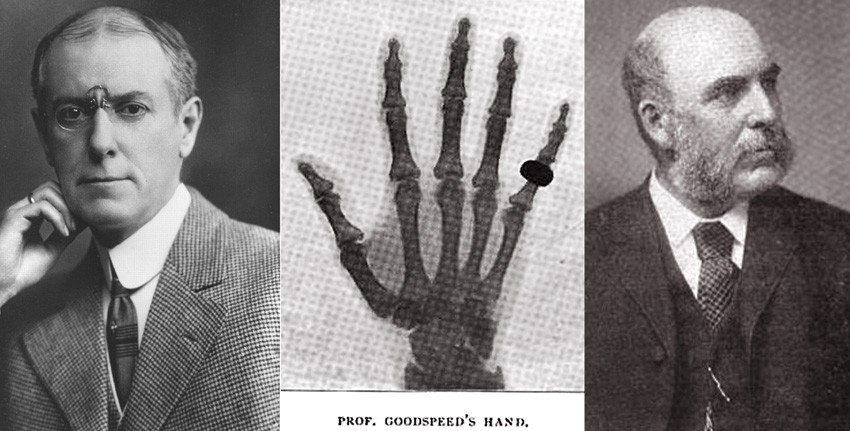

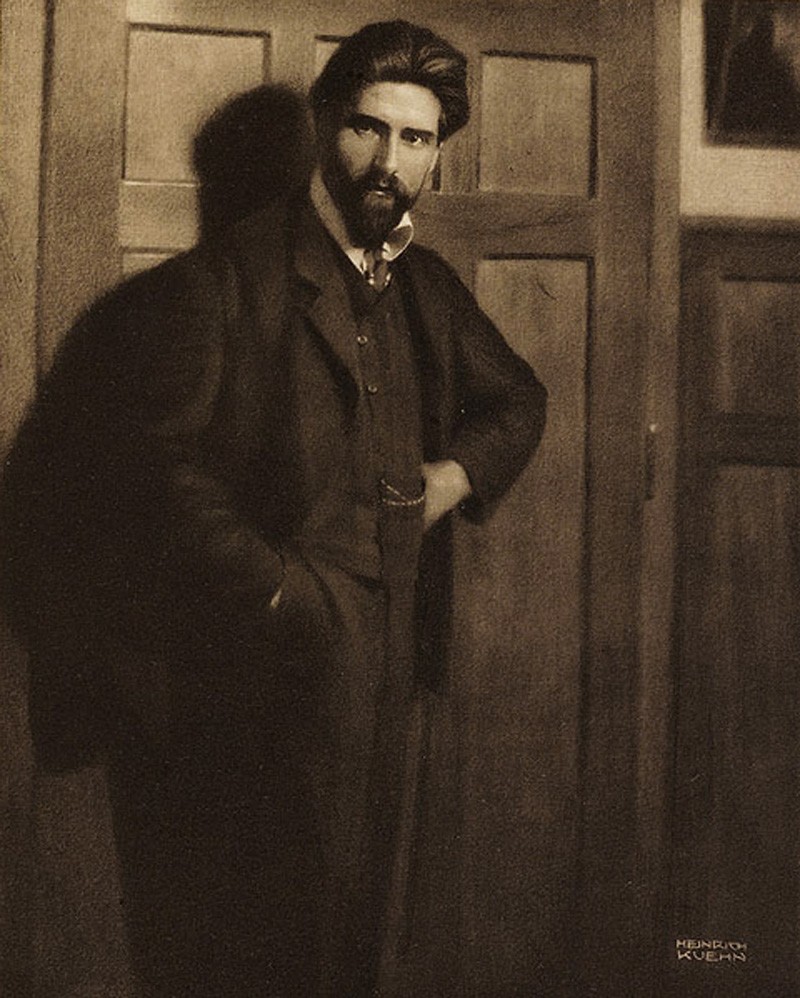

Left: self-portrait of Heinrich Kühn from October, 1901 issue of Photographisches Centralblatt; Middle: detail: multiple-color lithograph by Munich illustrator Fritz Rehm for German dry plate manufacturer Otto Perutz; Right: detail: Peter Behrens Jugendstil calendar. (all from PhotoSeed Archive) All three artists represented here were active participants in the Munich Secession at the end of the 19th century, an important exchange of creative ideas and radical thought made real through their own works. Behrens, whose work is in the permanent collection at the Neue Galerie, later went on to be one of the founders of the German Werkbund, a German modernist arts & crafts movement founded in 1907.

After emerging from the subway at 86th street from Grand Central and walking towards Fifth Ave., I spied a lamppost promotional banner for the show, complete with a readymade arranged beneath it: a toilet bowl cast off near the curb and the activity of the street all around it. For those game enough, New York is the kind of place where street photography could easily supplant any type of planned tourist activities, and so my inner muse, taken with the scene, made a few quick frames before venturing a short distance to the entrance of the impressive pile located at 1048 Fifth avenue-a New York landmark completed in 1914 by Carrère & Hastings– the same architectural firm that built the New York Public Library.

The sweeping wrought-iron staircase seemed a perfect fit for whisking visitors to the third floor exhibition galleries at the Neue Galerie, where some of the breathtaking landscape work of Kühn was on display in the form of vintage, large format gum-bichromate prints. An enlarged exhibition panel above the visitors at center is taken from the photograph “Mary Warner and Edeltrude on the Brow of a Hill”, ca. 1908-originally taken by Kühn on a color Autochrome Lumière plate, first introduced in 1907. PhotoSeed Archive photograph by David Spencer

The converted Georgian-style townhouse was originally built for industrialist William Starr Miller II (1856-1935) and purchased in 1994 by art dealer and museum exhibition organizer Serge Sabarsky and businessman, cosmetics heir and art collector Ronald Lauder. German for “New Gallery”, the Neue Galerie is a museum featuring early 20th century German and Austrian art and design, which recently celebrated it’s 10th anniversary in November, 2011.

The 4th gallery exhibition space, titled “Family Drama”, is taken up at right by a dark cherry-stained wood lattice panel: a re-creation of the backdrop Kühn utilized for some of his portraits. Photograph courtesy of the Neue Galerie.

One of many portraits Kühn used the backdrop for was for this study of Tyrolean sculptor and painter Hans Perathoner. (1872-1946) Taken ca. 1906-1907, the portrait was reproduced as a hand-pulled photogravure in Camera Work XXXIII (1911). Image courtesy of Photogravure.com

In doing background for this post, I learned from The New York Times that the current Kühn exhibit is only the 2nd show of photography to be featured at the museum, and is curated by Kühn scholar Dr. Monika Faber, a champion for his and other work from this period, and currently the Director of the Photoinstitut Bonartes in Vienna.

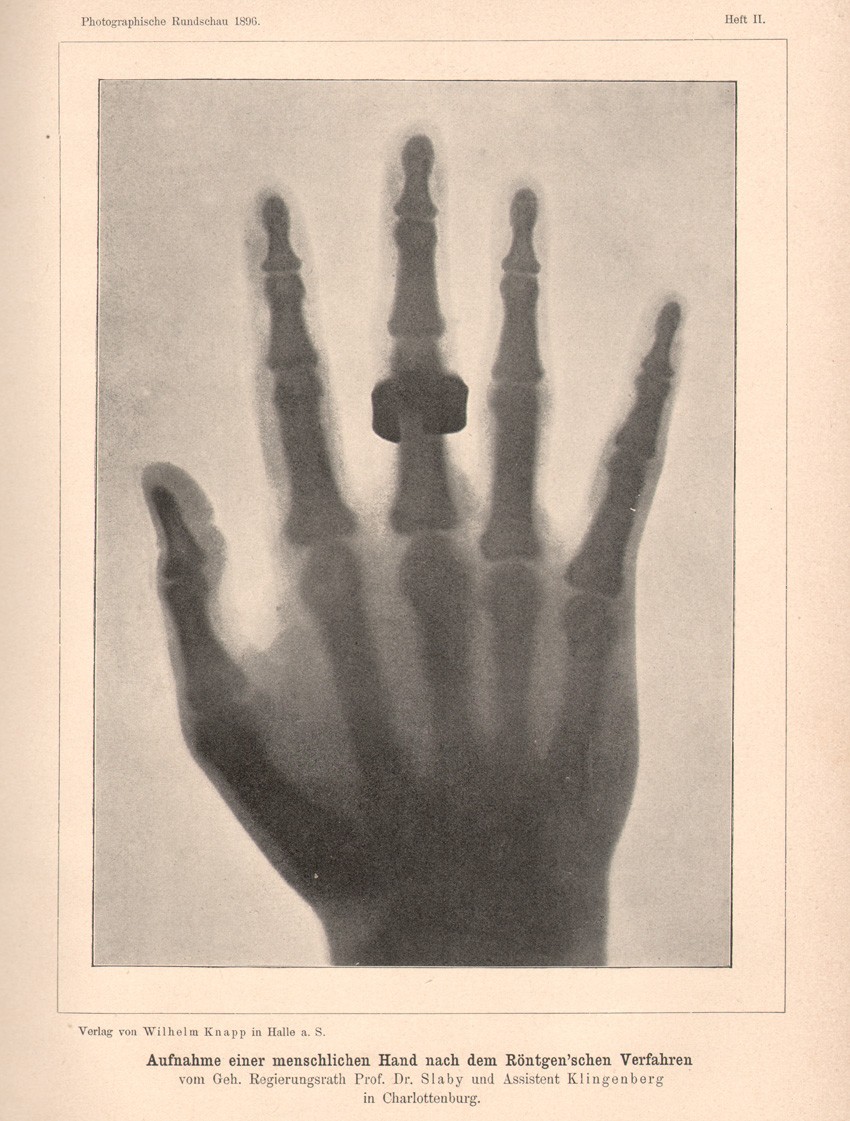

Tea Still-life, Version III (Teestilleben, III. Fassung) is a fine example of Kühn’s still-life work showing his masterful control of light. Later reproduced as a hand-pulled photogravure by the Berlin atelier Otto Felsing and appearing in the January, 1908 issue of Photographische Rundschau , it was also most likely taken in one of his new home photographic studios on Richard Wagner Strasse, designed by Wiener Werkstätte founders Josef Hoffman and Koloman Moser. Image: (13.1 x 17.7 cm) from PhotoSeed Archive

A contributor to and co-editor of the essential 2010 volume “Heinrich Kühn: The Perfect Photograph,” Faber can be seen in this video describing Kühn’s role in the development of artistic photography as well as his relationships with Alfred Stieglitz, who he first met in 1904 (Stieglitz had known of Kühn since 1894) and Edward Steichen in 1907, whose atmospheric work, we learn in the video, was inspired by some of Kühn’s massive (for the time) gum-bichromate photographs featuring sweeping and expansive Tyrolean landscapes.

The 2nd gallery exhibition space, titled “Early Success”, features a re-creation at far right of the 6th exhibition that took place at the Alfred Stieglitz gallery “291” on Fifth Avenue-from April 7-28, 1906. The Viennese and German photographers Heinrich Kühn, Hans Watzek and Hugo Henneberg-known as the Cloverleaf or Viennese Trifolium, all had vintage, massive frames on display. Photograph courtesy of the Neue Galerie.

Not surprisingly, I soon discovered taking pictures is off-limits in the second and third floor exhibition rooms of the museum, which made it easier for me to scribble notes and not worry about the supplemental visuals for this post, most of which I’ve pulled from the PhotoSeed Archive. Emerging on the third floor, I first ducked into gallery 5 to take in a video narrated by Neue Galerie director Renée Price on Kühn’s pioneering 1907 involvement, along with Stieglitz and Steichen, with color Autochrome Lumière plates. I talked with the guard near the entrance who smiled when I asked how many times he had already seen it. Needless to say, he probably will not take the bait to see it again here on his day off, but you of course should.

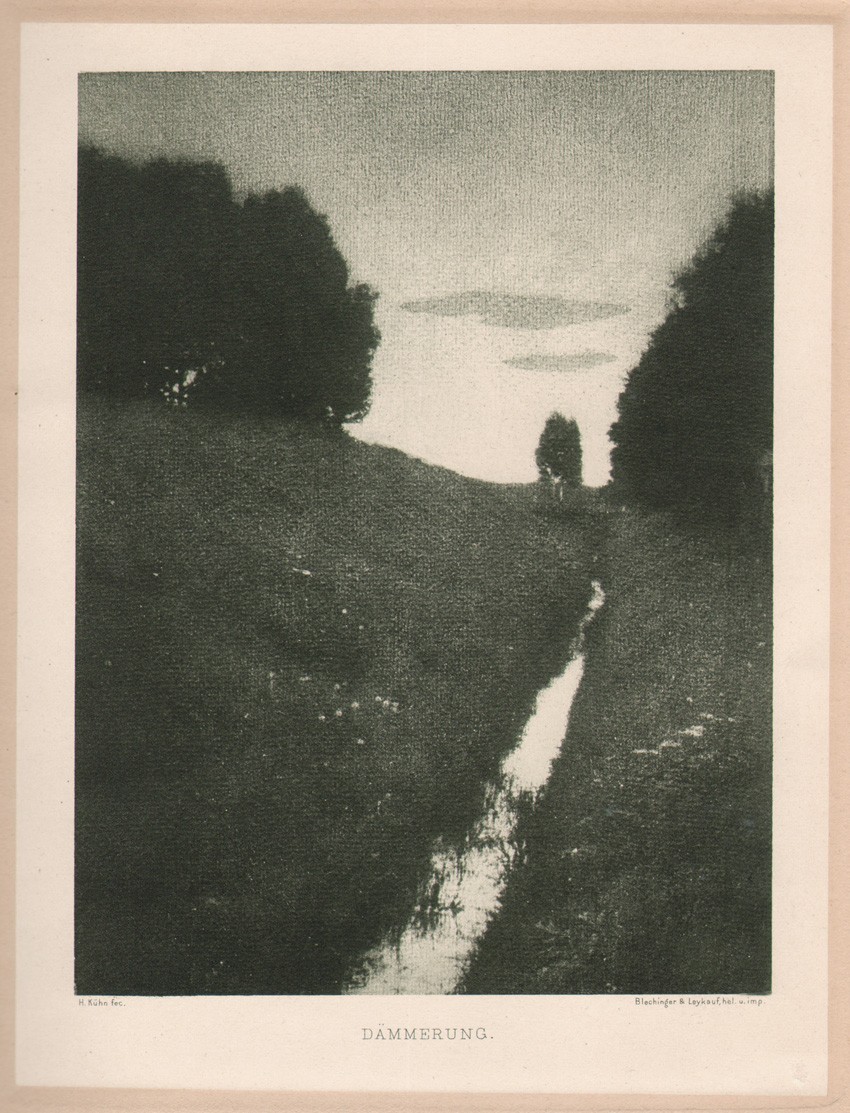

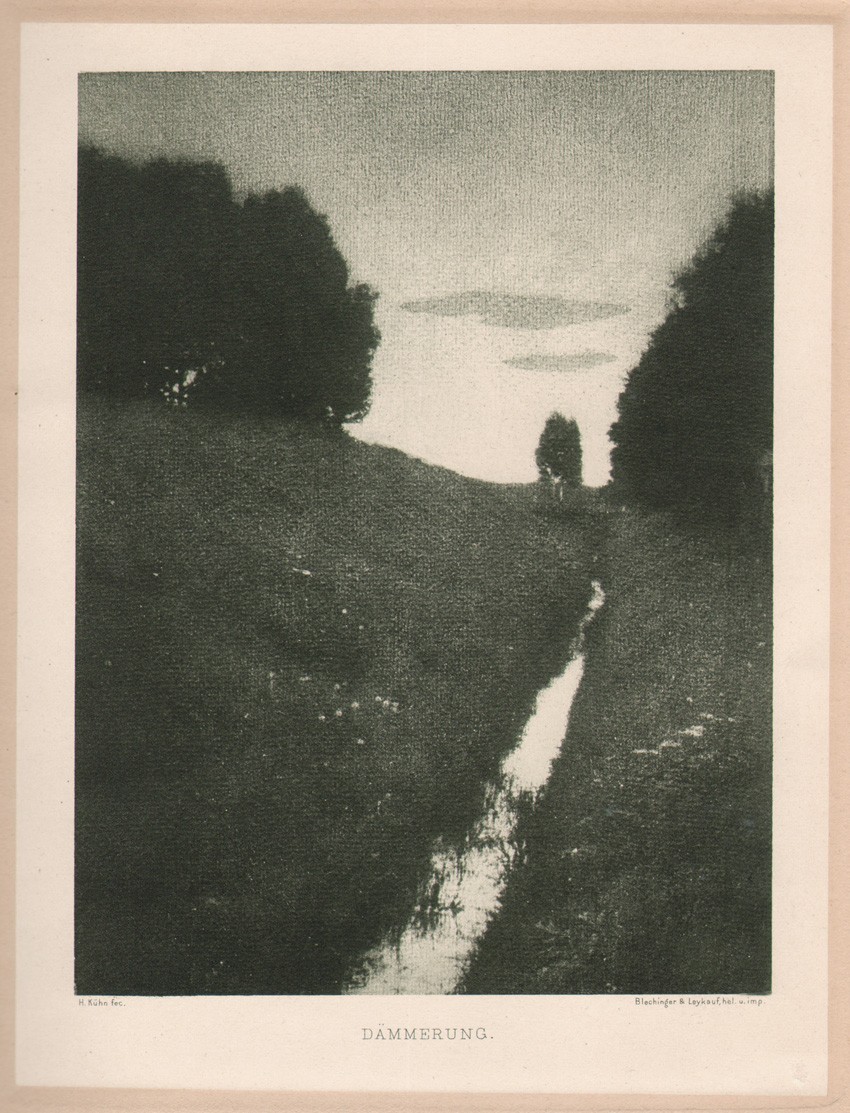

One of the original vintage framed photographs on display in the “Early Success” gallery was this landscape study titled “Twilight” (Dämmerung), which Kühn did in 1896. This hand-pulled Chine-collé photogravure version published in the important Austrian photographic journal Wiener Photographische Blätter in February, 1897 surely does the original an injustice: a bi-color gum bichromate print (enhanced with watercolor) that is certainly unique. Image: (15.6 x 11.8 cm) PhotoSeed Archive

The show is arranged in five galleries, with a total of 105 vintage photographs in a variety of photographic media. In addition to the aforementioned work by Stieglitz and Steichen, Kühn’s fellow Viennese Trifolium partners Hans Watzek and Hugo Henneberg are also included, as well as select examples by Photo-Secession members Frank Eugene, Gertrude Kasebier, George Seeley and Clarence White.

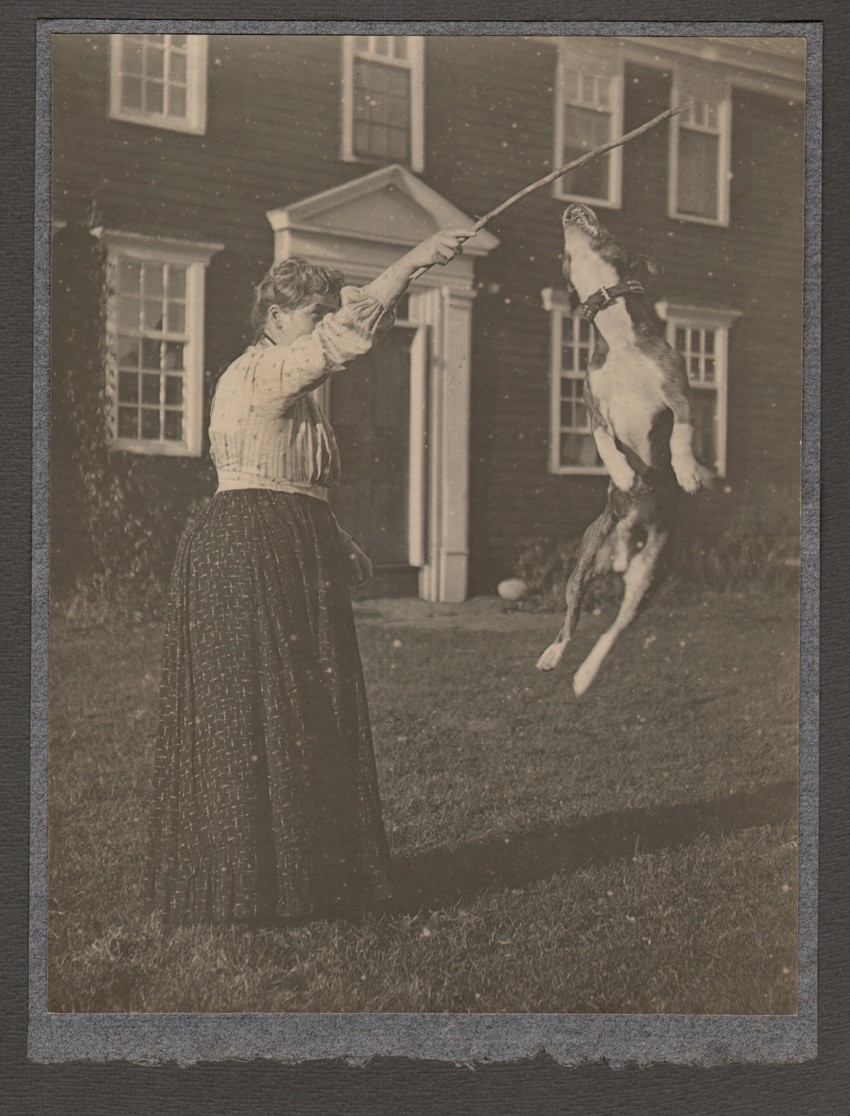

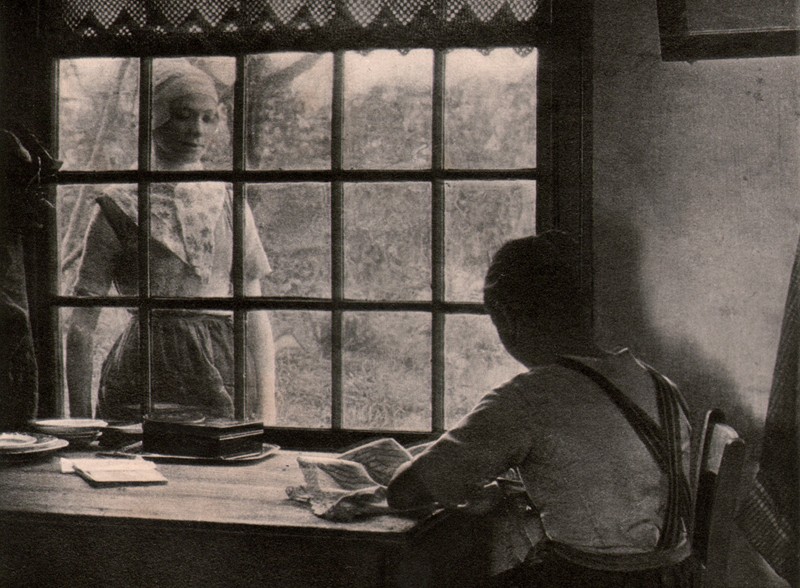

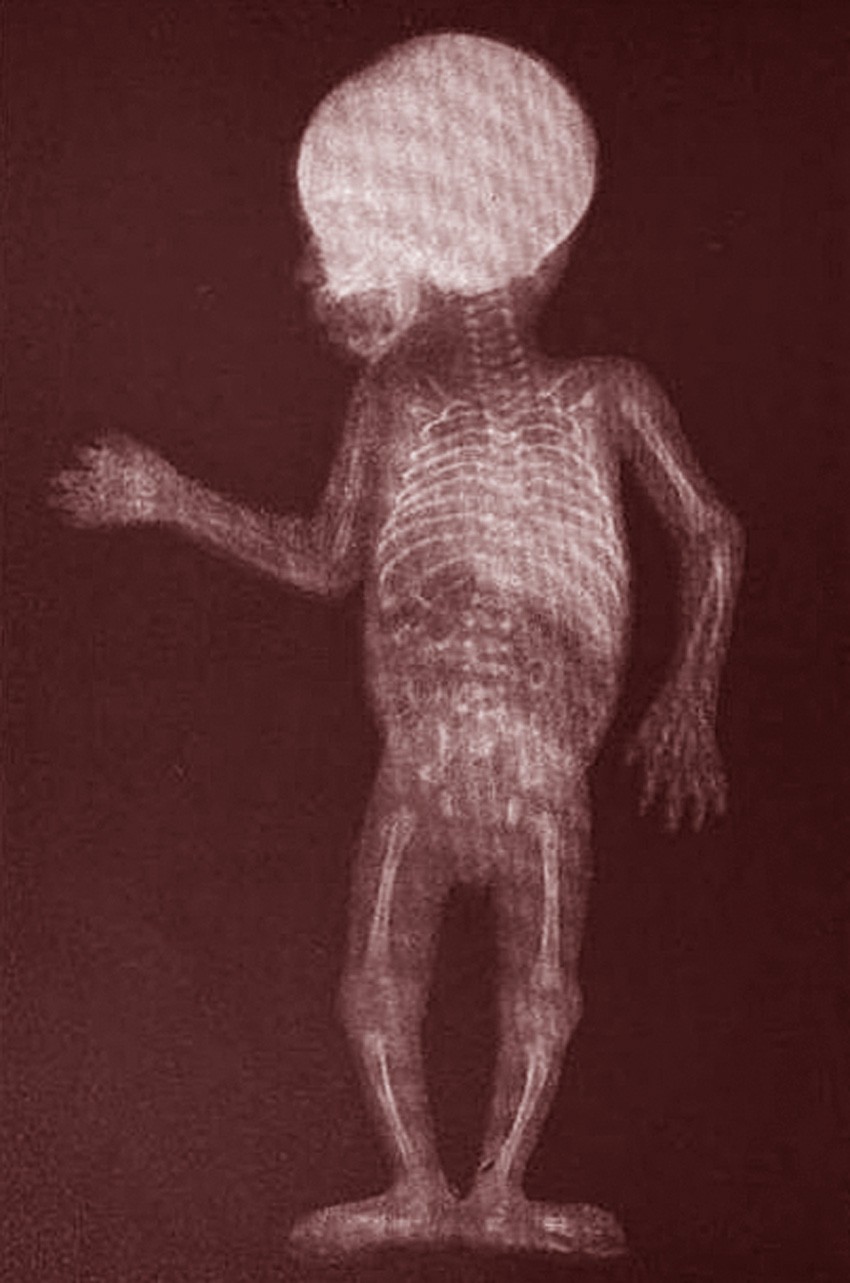

White Excursion, (Weier Ausflug) from ca. 1905, is a fine early example of genre landscape study by Kühn incorporating his family members taken in the Tyrol. (most likely nanny Mary Warner and daughter Edeltrude) After the 1907 introduction to the public of Autochrome Lumière plates, he would create elaborate staged scenes similar to this but with specially made clothing worn by his models in order to take advantage of the added color dimension. Image: from September, 1908 issue of Photographische Rundschau: ( 17.7 x 13.1 cm) PhotoSeed Archive

The two galleries I found most fascinating were the 4th gallery, which the museum assigns the collective title “Family Drama” and the 2nd gallery, called “Early Success”. In Family Drama, a massive, dark cherry-stained wood lattice panel forms the backdrop along one wall which has been installed specially for this exhibit. According to a museum guard, the panel blocks large windows overlooking Fifth Ave. The prop is a subtle and welcome touch for those familiar with some of Kühn’s portrait work, which often balances expanses of dark (the paneled background) with select highlights for the figure posed in front of it.

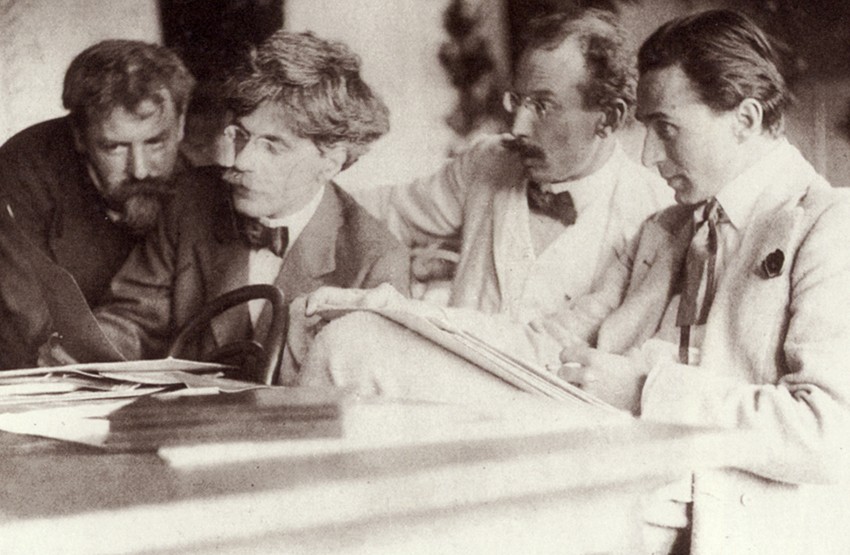

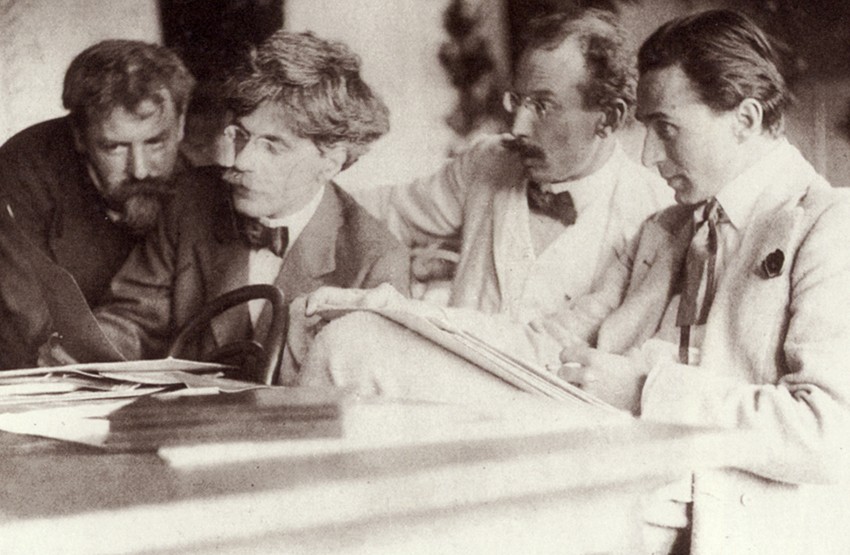

There were several examples of original vintage prints taken by American Photo-Secession founder member Frank Eugene (1865-1936) included in the show, in order to show Kühn’s active participation in and acceptance by the upstart Photo-Secession (founded 1902) in America. In this study taken in 1907 by Eugene, who can be seen at far left of frame, Alfred Stieglitz, Heinrich Kühn and Edward Steichen (far right) examine Eugene’s photographic work. Detail: platinum print, Yale Collection of American Literature: from: Wikimedia Commons

According to a caption in this gallery, these panels were originally intended to be moved around as part of a photographic studio, and were (presumably) designed by Wiener Werkstätte founders Josef Hoffman and Koloman Moser for Kühn’s Innsbruck home located on Richard Wagner Street, where he lived with his children and English nanny Mary Warner from 1906-1919 (another studio in the home featured white paneling). Kühn’s ability to move the panels depending on exterior lighting conditions-from windows, skylights, and reflected means-were a way of giving his portrait backdrops a distinctive style. A means to an end in order for him to maintain fastidious control of his pictorial output.

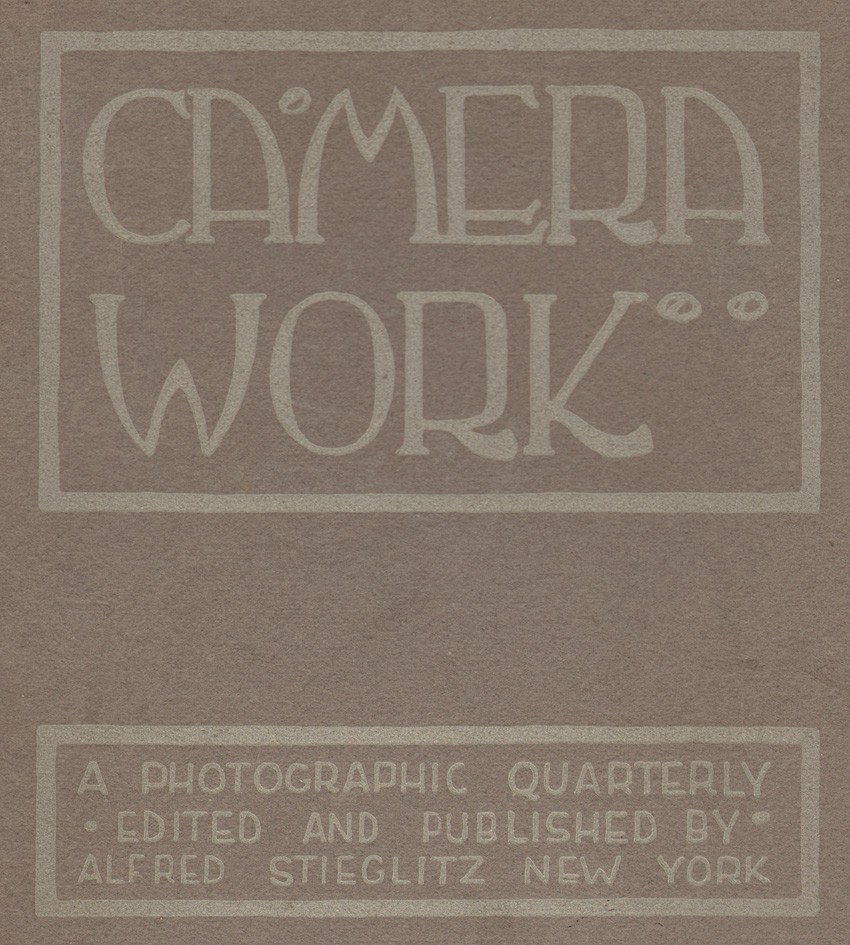

The 3rd gallery exhibition space was the smallest, and was an homage to the importance of the American Photo-Secession journal Camera Work, edited and published by Alfred Stieglitz. Seen here on both sides are all twelve vintage select plates from the journal as well as a framed gum bichromate photograph: “Anna with Mirror” done by Kühn in 1902 and later published in Camera Work XIII in 1906. Photograph courtesy of the Neue Galerie.

Speaking of control, another photographic caption in this gallery stated Kühn went so far as to have special clothing tailored in hues of black, white and gray for his children to wear while they posed for these portraits. Later, this also applied after 1907, but with colored clothing worn by them as well as Mary Warner while he made some of his most famous images in outdoor settings using the brand-new Autochrome Lumière plates.

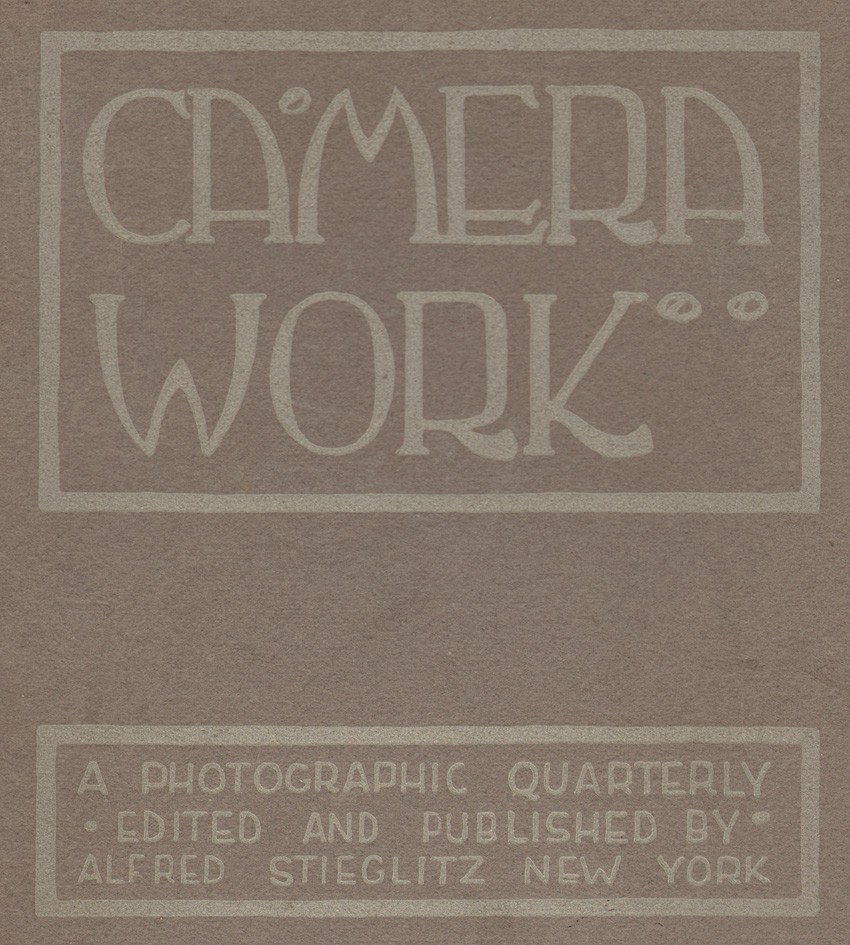

The distinctive cover of “Camera Work” featured Art-Nouveau typography done by American Photo-Secession founder member Edward Steichen, who was also an accomplished painter at the time he hand-designed the lettering sometime in 1902 before traveling to Paris to live and study. Detail of entire cover shown. top: logo: (8.6 x 14.0 cm) PhotoSeed Archive

Walking over to the adjoining 2nd gallery, Early Success, the idea of gallery repetition is repeated along the long dimension of the space. Here, the idea of the famous Stieglitz “291” gallery is hinted at, with pleated, olive-drab fabric lining the lower portion of the wall while early 20th century reproduction period spotlights are aimed toward massive examples of colored and monochrome gum-bichromate prints.

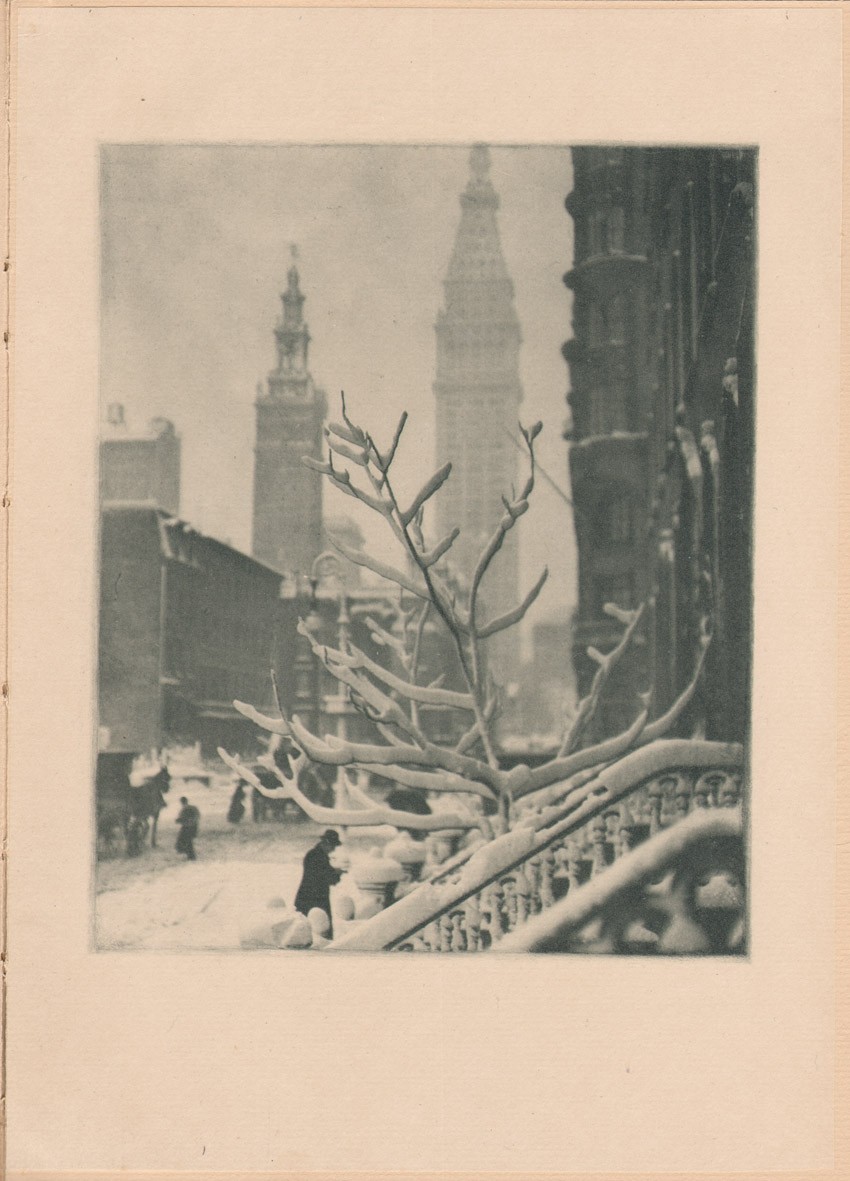

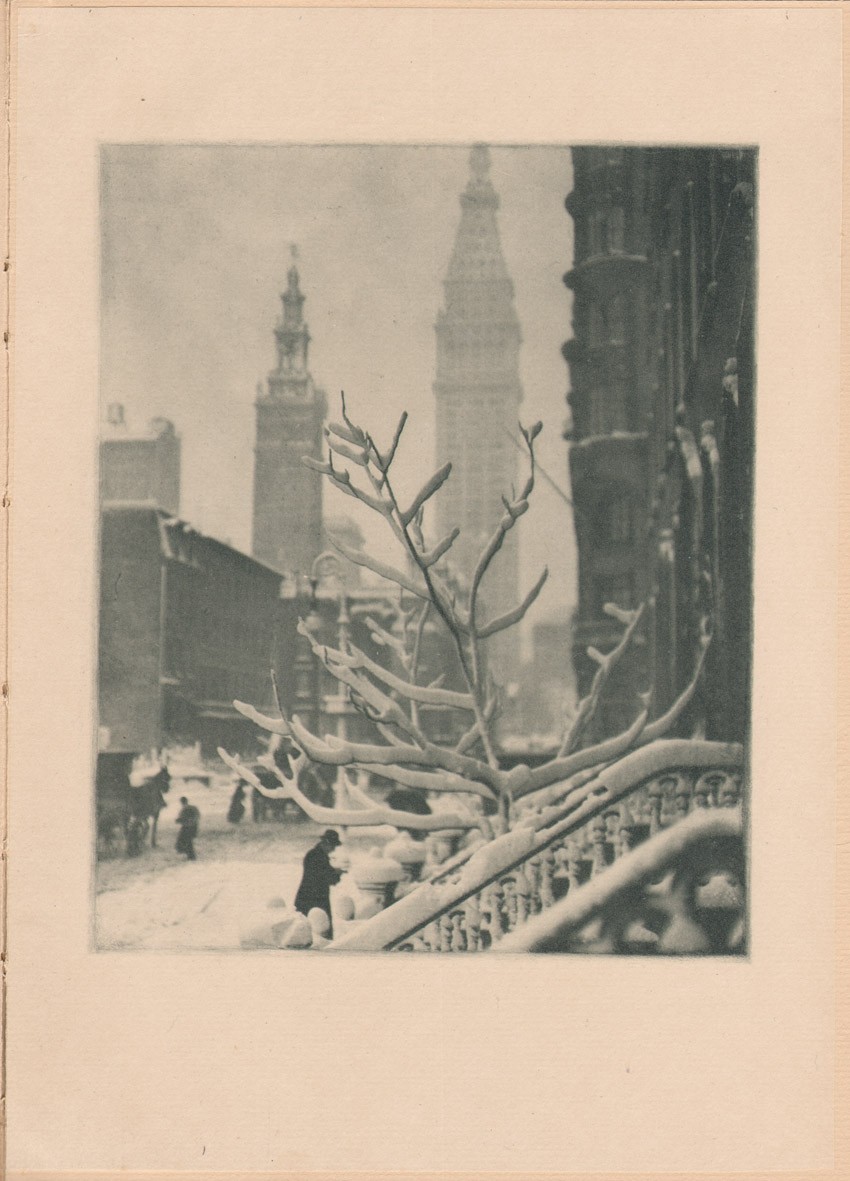

One of Alfred Stieglitz’s signature New York photographs is “Two Towers — New York”, a cityscape taken in 1911 showing his masterful balancing of shades of gray in a complex urban environment. The following description appears in “The Key Set”, volume 1: “The view looks south from a stoop on the west side of Madison Avenue, toward the towers of Madison Sqaure Garden (left) and the Metropolitan Life Building (right).” This plate, with full support shown, from Camera Work XLIV, 1913 (image: 20.5 x 16.0 cm | support: 28.1 x 20.0 cm ) From: PhotoSeed Archive

As I counted 29 framed prints in this room alone, the 291 wall is intended to showcase an approximation of the actual work (loaned from the Stieglitz bequeath at the Metropolitan as well as other institutional and private collections) from Viennese Trifolium members Kühn, Henneberg and Watzek. It was truly an extraordinary moment to be able to see these large-scale photographs up close, further elucidated on for their time as follows in a gallery caption:

The scale of the prints themselves may have convinced a broader public that photographs might be an artistic medium in its own right.

Kühn of course was the star in this room, with some of his earlier successes shown dating to the mid 1890’s. The cloverleaf Trifolium ceased to exist after 1903, once Watzek died and Henneberg soon turned his attention to etching.

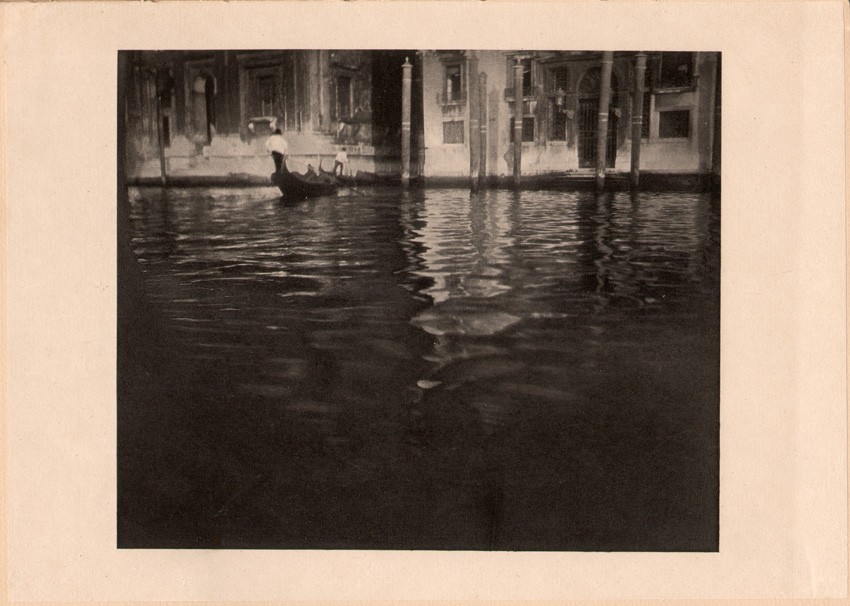

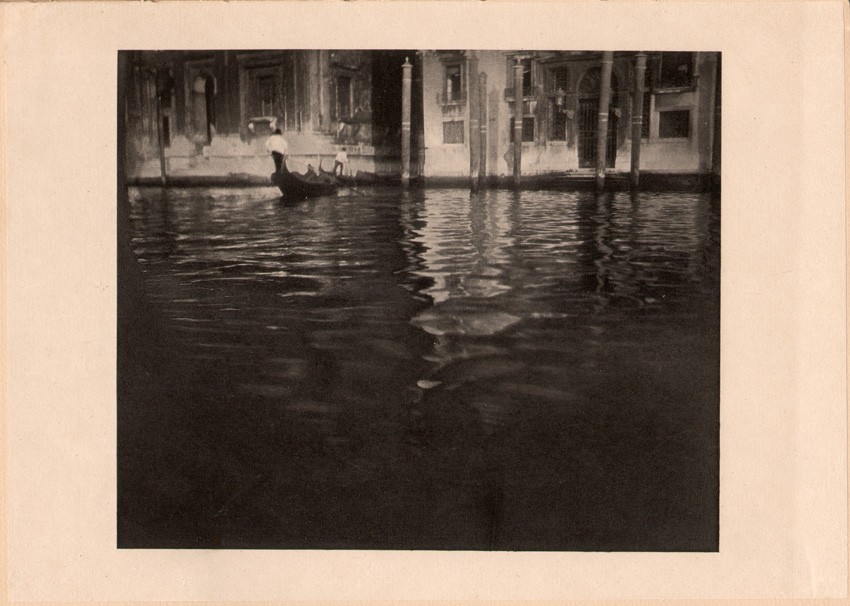

In the same year (1907) Heinrich Kühn had sat down with Stieglitz, Edward Steichen and Frank Eugene to discuss their work, Steichen’s own exploration of shades of gray by means of the the camera took shape in this waterway study of a gondolier navigating a Venetian waterway. Initially titled “Late Afternoon – Venice”, the work was first published in the Steichen number of Camera Work 42/43 (1913) as a duogravure before Stieglitz had it reprinted as a hand-pulled photogravure on Japan tissue for Camera Work 44, (1913) where it was simply titled “Venice”. This plate, with full support shown, from Camera Work XLIV, 1913 (image: 16.7 x 20.1 cm | support: 19.9 x 28.0 cm ) From: PhotoSeed Archive

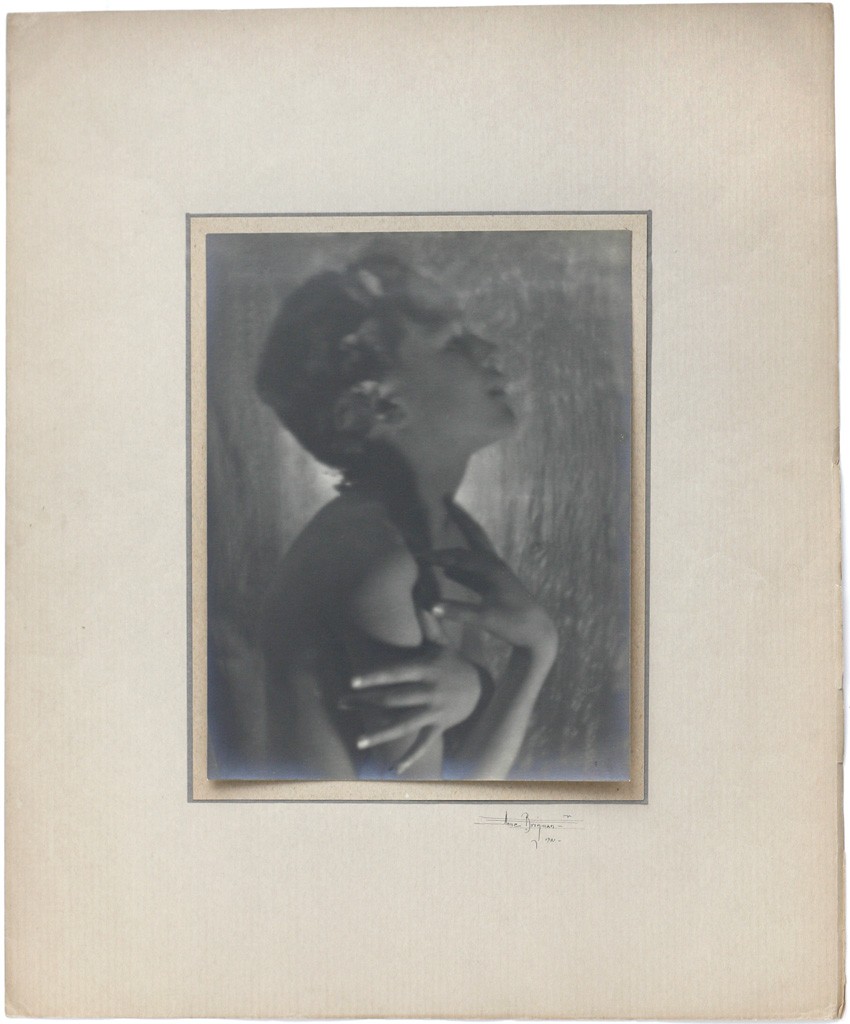

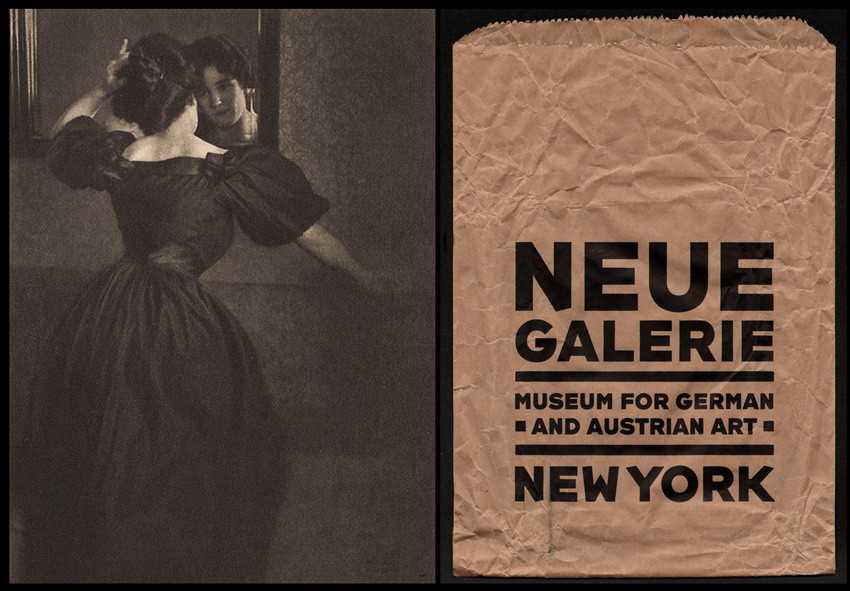

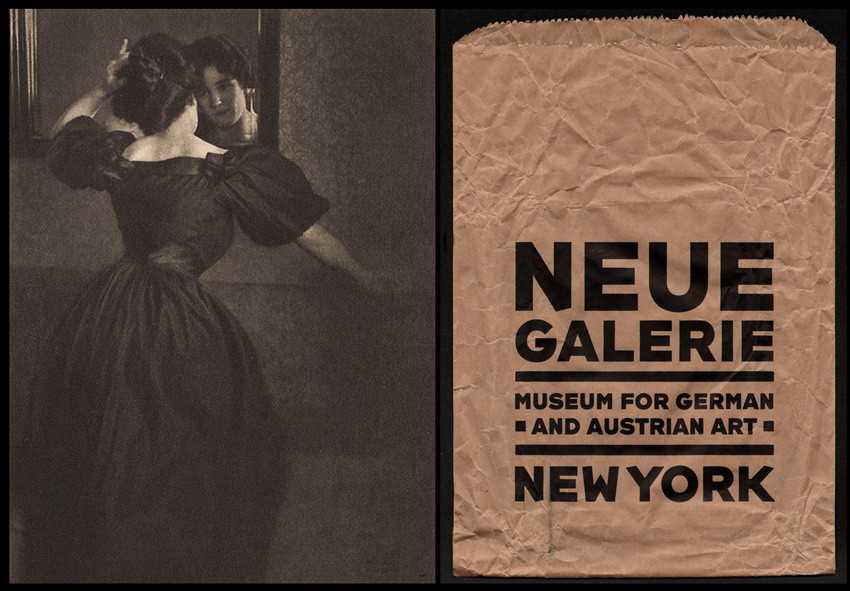

Finally, in the third gallery, a bridge for how Kühn and his contemporaries were embraced and given credibility in the form of 12 select images from the Alfred Stieglitz journal Camera Work are shown. The small room is further anchored on one side by a large gum-bichromate print titled Anna with Mirror, a 1902 genre study by Kühn showing a young woman from behind fixing her hair while reflected in a mirror.

Left: “Anna with Mirror”, taken by Kühn in 1902, was titled “Girl with Mirror” when Alfred Stieglitz included it as a photogravure plate in Camera Work XIII in 1906. A reproduction greeting card of the image was included in a boxed set purchased by this author from the Neue Galerie book store and carried home in the brown-paper bag at right, a fine example of modern typographic art for sure. Left: 19.5 x 14.4 cm: image courtesy: Photogravure.com Right: paper bag: 28.2 x 19.2 cm

Reproduced by Stieglitz as a photogravure in Camera Work in 1906, the Neue Galerie chose to include a reproduction of it, along with five of Kühn’s other photographs, in an affordable set of greeting cards sold in their first floor gift shop: a nice memento and excuse for future correspondence procured by this visitor on my way out to Fifth Ave.