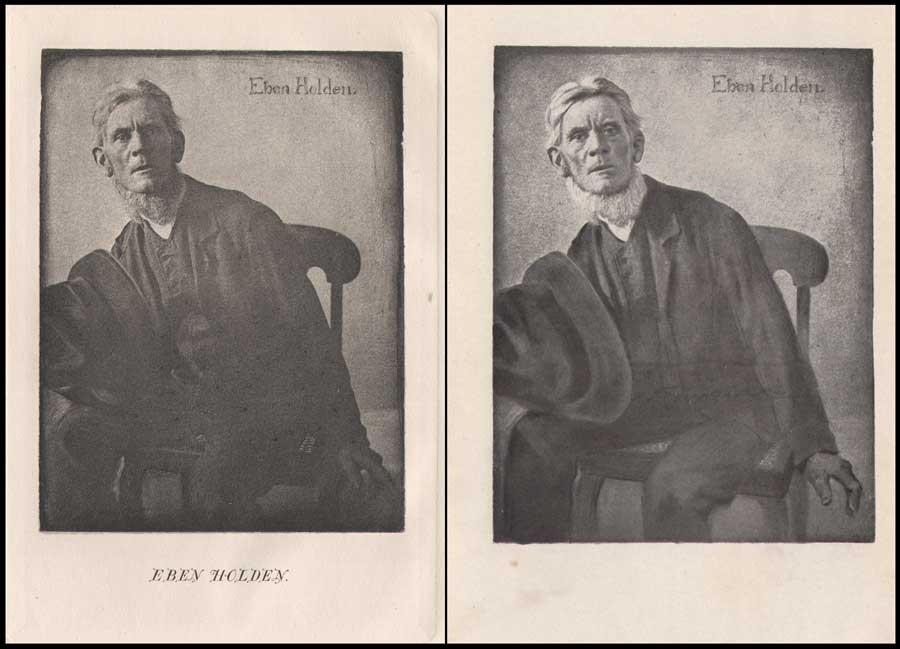

Surreal would be a good word for it. On the evening of Friday, November 4, 1904, the touring company of the Broadway flop Eben Holden made its way to a performance at a building called the Auditorium on S. 2nd Street in downtown Newark, Ohio.

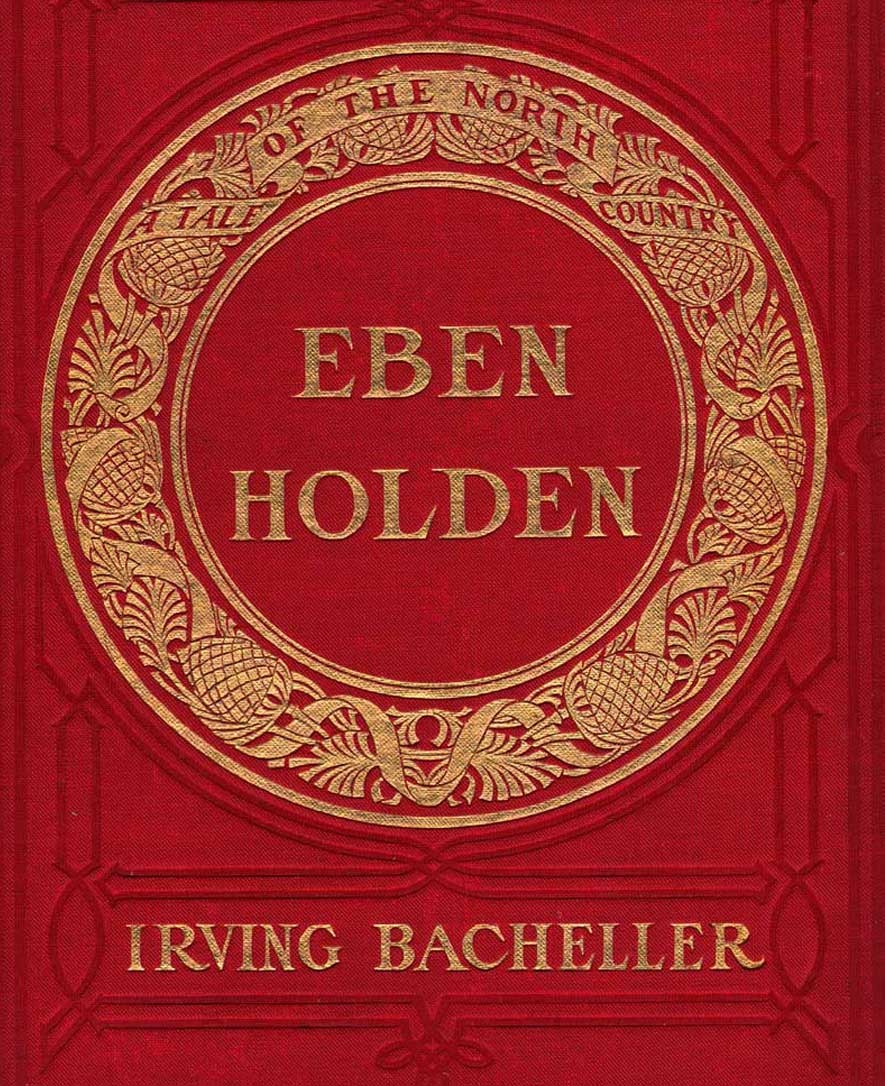

Detail: Cover for “Eben Holden: A Tale of The North Country”: Edition de luxe by Irving Bacheller. Lothrop Publishing, Boston: 1903. Gilt-engraved decorative cloth with circular design featuring a design of a ribbon interlaced with pinecones and leaves: 21.0 x 14.2 cm: One of the best selling novels from the very beginning of the 20th Century, this edition features 12 photogravure plates by photographer Clarence Hudson White. from: PhotoSeed Archive

Most likely in attendance that night? Clarence Hudson White, (1871-1925) the world-renowned pictorialist photographer who was a recent founding member of the American Photo-Secession and current Newark resident. Only two years earlier, he had taken a series of photographs using his Newark neighbors as models for a special edition of Eben Holden that had been made into this very play.

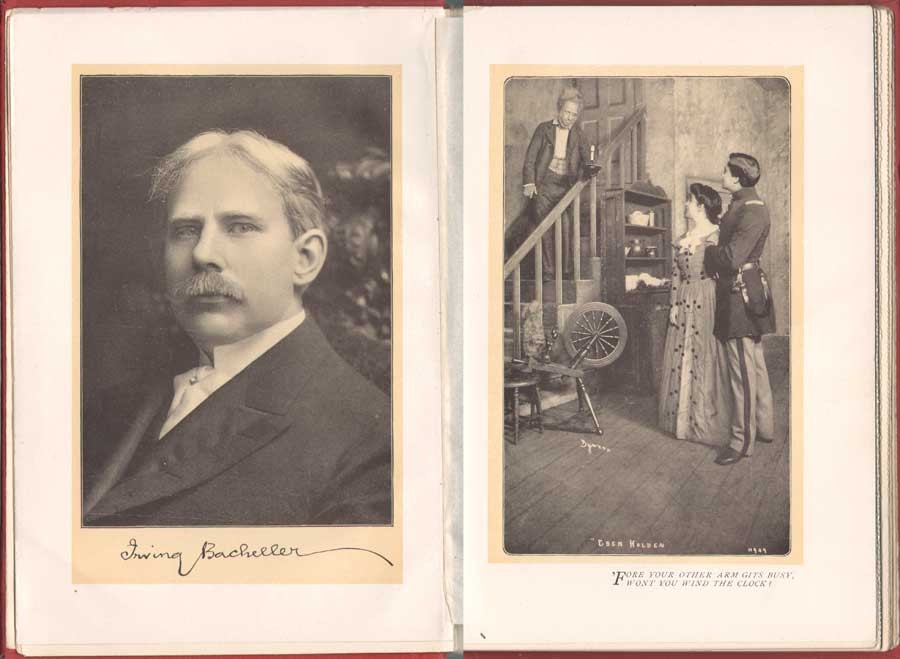

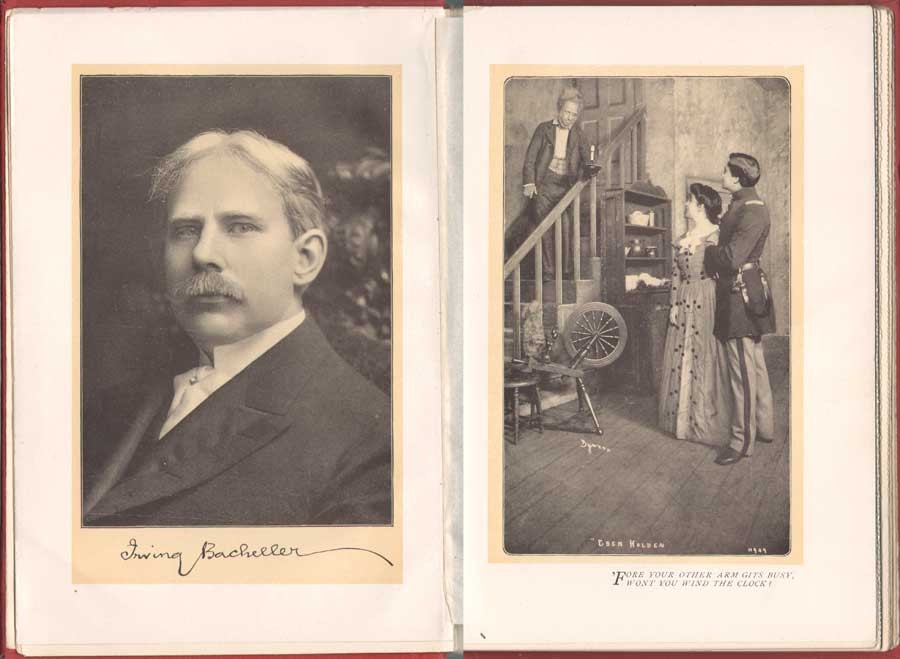

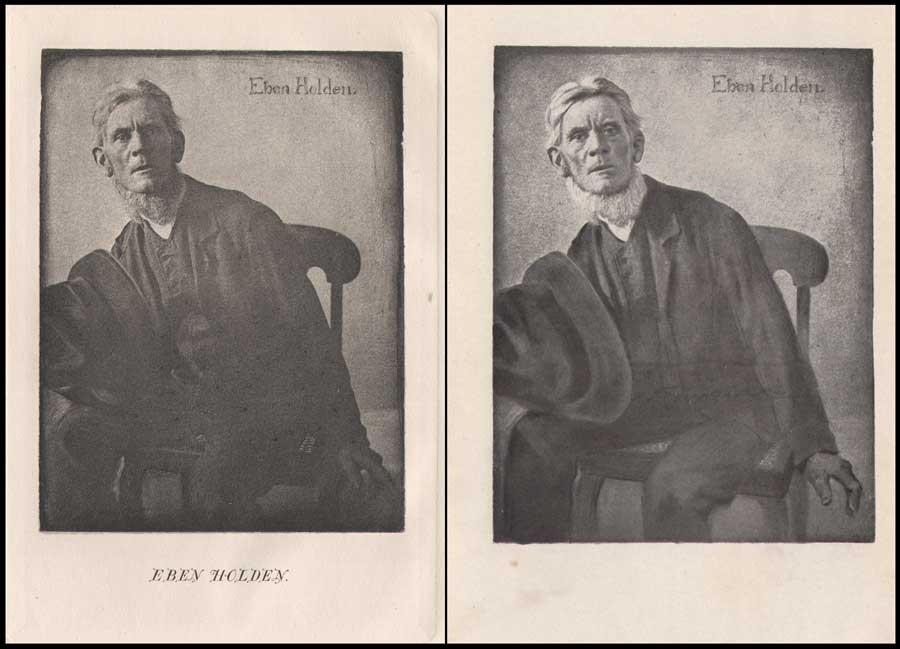

Written by American journalist and author Irving Bacheller, (1859-1950) the story is a classic rags to riches tale that captivated the masses in the new American century when first published in July of 1900, eventually selling over 1 million copies. The setting at the beginning of the novel is the “North Country” of Northern Vermont , the Adirondack’s and St. Lawrence River Valley of the 1840’s and 1850’s. It tells the coming of age story of William Brower, orphaned at the age of six after his parents and older brother accidentally drowned as well as his relationship with Eben Holden, a farm hand who rescued “Willy” from the cruel fate of an orphanage

But this post is part collecting story, a kind of hunt for treasure, or “spondoolix” as “Uncle Eb” would say in one chapter-his country ways and lack of education brought into sharper focus for the reader by Bacheller’s liberal usage of Holden’s spoken dialect.

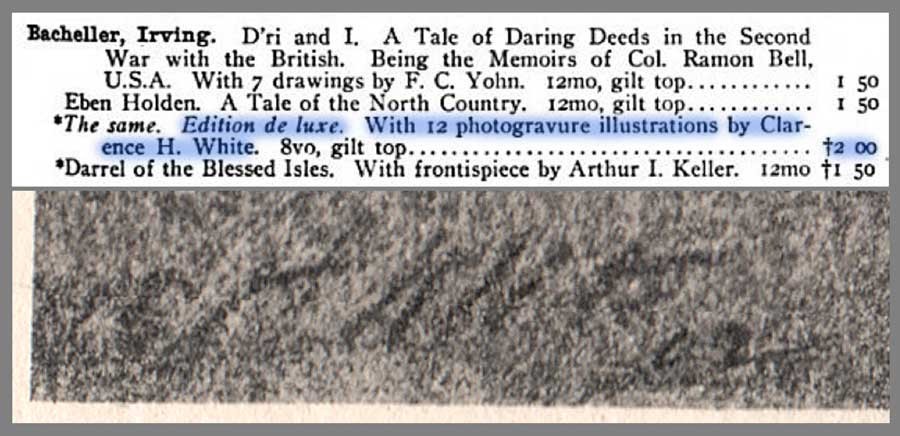

Detail: Top: listing for works by American author Irving Bacheller showing Edition de luxe of Eben Holden highlighted in blue: from: Illustrated Catalogue of Books Standard and Holiday 1903-1904: Chicago: A.C. McClurg and Company: 1903: p. 217 (the † denotes it is a work of fiction, published since November 1, 1902, under the rules of the American Publishers’ Association. (from: Hathi Trust)Bottom: close-up detail showing autograph for CH White 02 at bottom left corner of representative photogravure plate from the Edition de luxe: from: PhotoSeed Archive

The Hunt is on

I consider myself a newbie collector, but one of the first things I put on my list 15 years ago when I first started out was one particular impression of Eben Holden rumored to have been illustrated by hand-pulled photogravures by White, the aforementioned famous photographer.

My curiosity had been piqued after seeing the volume listed in several bibliographies, typically stating the 1900 date. One such entry in author Christian A. Peterson’s Annotated Bibliography on Pictorial Photography did give me hope the work existed, even though finding one in the internet age would prove to be quite the challenge:

The Museum of Modern Art, New York, holds what is probably a unique copy of this book, comprised of the Lothrop text pages bound in leather, with an inscription by White and ten photogravure illustrations by him, including the portrait of Holden. (1.)

Because the novel had been such a success a century earlier, the reality of upwards of 500 vintage copies for sale on the web at any one time was daunting. My course of action however was simple, and eventually effective: send out a mass number of emails to every bookseller in the U.S. listing a copy from a suspect 1901 edition I had honed in on inquiring if it contained any photographic illustrations.

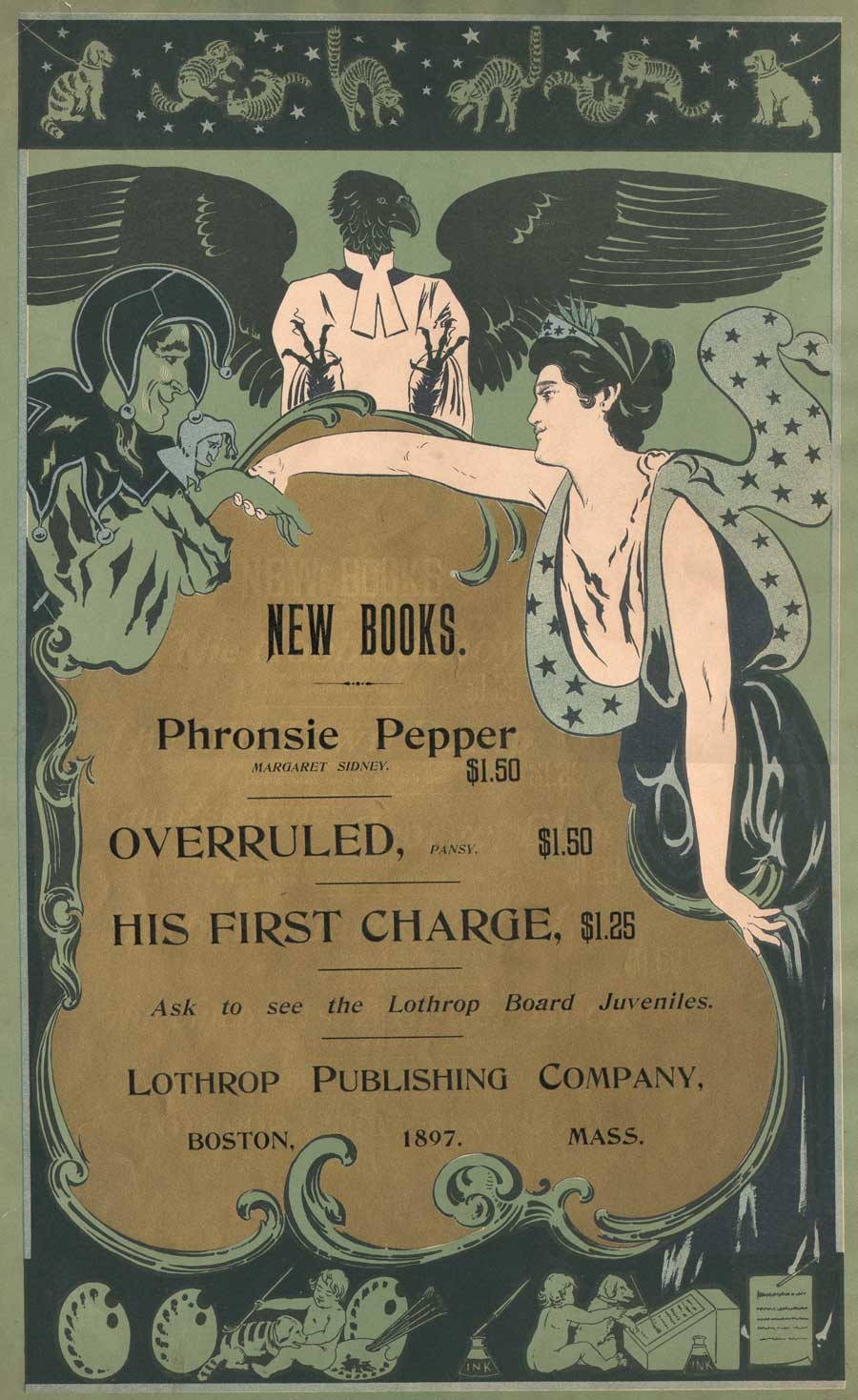

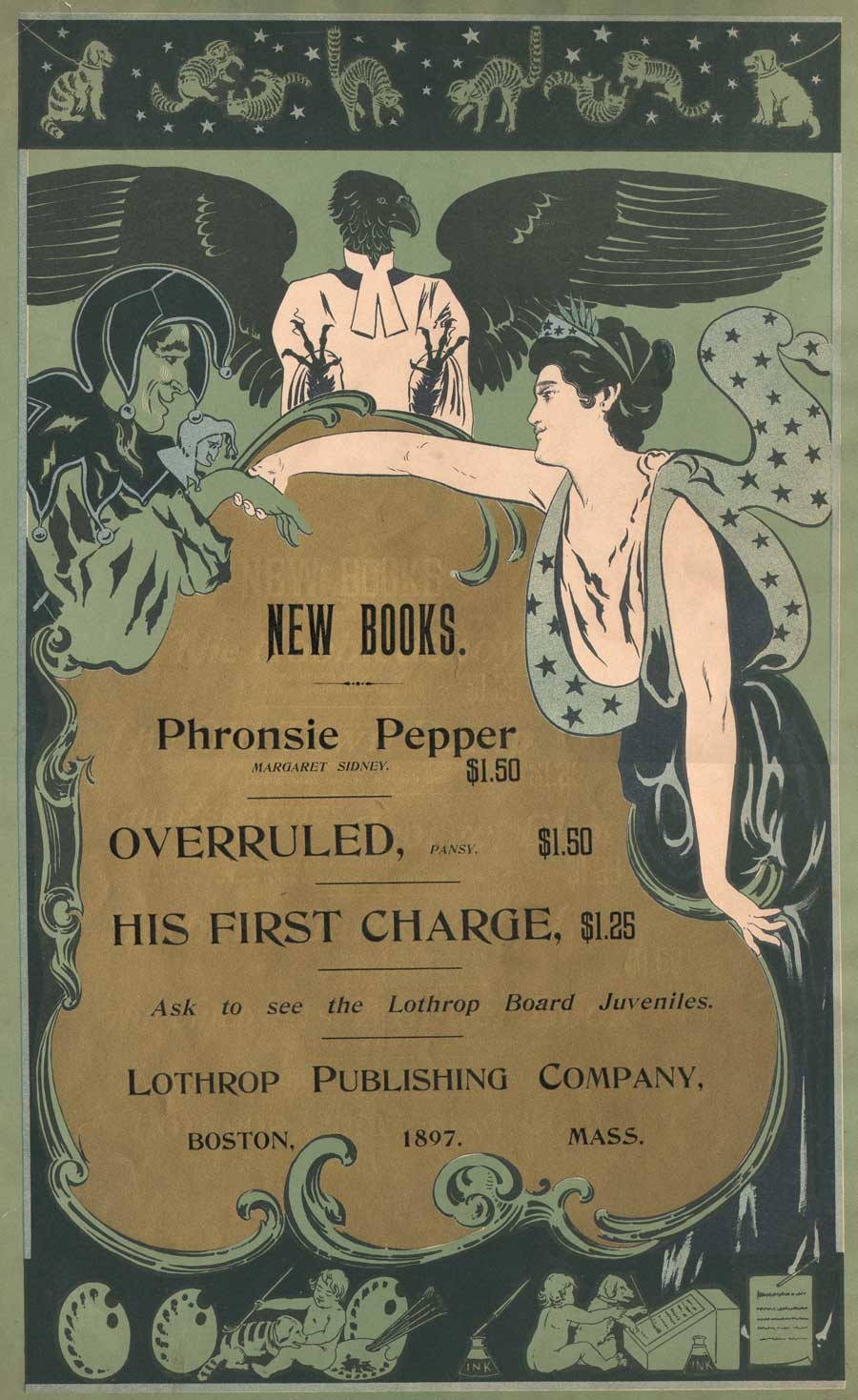

Broadside advertising poster for Lothrop Publishing Company of Boston: 1897: artist: William Schumacher: American: (1870-1931) multiple-color lithograph printed on wove paper: 52.7 x 34.0 cm. Speaking of the beginnings of Eben Holden in the year 1897, author Irving Bacheller said “had unsuccessfully offered the first ‘Eben Holden’ as it then stood to two juvenile publications; but as I happened to be just starting off on a vacation at that time, I determined myself to see the Boston firm, which was the Lothrop Publishing Company. I met the editor, Mr. Brooks, at the Parker House, and told him the story as I had written it. He immediately saw the possibilities in it and declared I had a big thing if I could carry it out as it should be.” (excerpt: “The Critic”: Oct. 1904) vintage broadside (trimmed) from: PhotoSeed Archive

And so eventually luck prevailed. In 2007, a bookseller in Idaho finally said yes, and a bucket item was now on my library shelf. But that was not the end of it, as Alice would say, things got Curiouser and Curiouser! Because collectors never stop looking, I soon stumbled upon a CT bookseller who knew exactly the significance of the White-illustrated impression, with an astronomical asking price. An excerpt from his description of the work stated:

Elusive and highly desirable work, absent from almost all museum and library collections devoted to photography, and one of only a very few photographically illustrated books produced by a leading member of the Stieglitz circle at the height of the Photo-Secession. (2.)

Top: detail: 1891 advertisement for The Estes Press (Dana Estes & Company) from “The American Bookmaker”. The woodcut shows the brand new Estes Press Buildings located at 192 Summer St. in Boston first occupied around 1890. The firm housed many different companies involved in the bookmaking process, including: “The celebrated engravers, John Andrew & Son have their studios in the upper story…”; J.S. Cushing & Co., (book composition) Berwick & Smith, (presswork) and E. Fleming & Co. (binding). These last three firms left Estes in 1894 and became part of the Norwood Press. (from: Hathi Trust) Bottom: detail: exterior photograph of Norwood Press from the 1897 volume “Boston Massachusetts” by George W. Englehardt. The original caption noted the firm was located “Fourteen Miles from Boston, on the New England Road” and “as a whole employing nearly three hundred hands.” This is where the Eben Holden Edition de luxe was printed. (from: Hathi Trust)

And so I sucked it in and didn’t purchase the second copy, which he told me he had originally purchased in Marlborough, NH. Eventually he sold it to a European collection, but I’ve since visited him several times and made a few purchases over the years, something I highly recommend rather than doing everything through e-commerce.

But then lighting struck again five years ago, when I purchased a second copy which had been personally inscribed by the author in 1911 to John A. Dix, then governor of New York state.

Curiouser? The first copy, fourth edition imprint stated Two Hundred and Sixty-fifth Thousand, March 12, 1901 and the second copy was for Two Hundred and Seventieth Thousand, September 18, 1903.

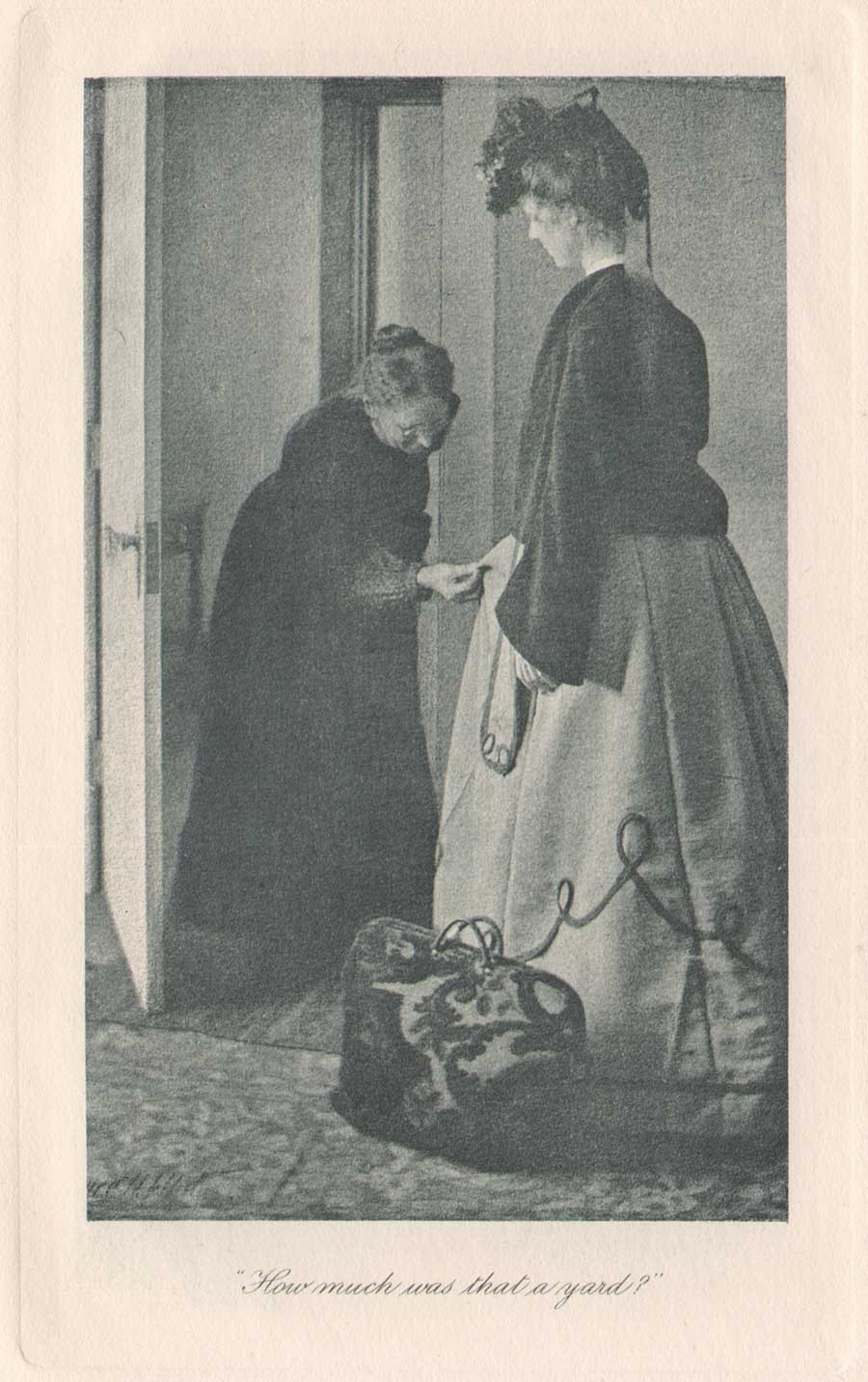

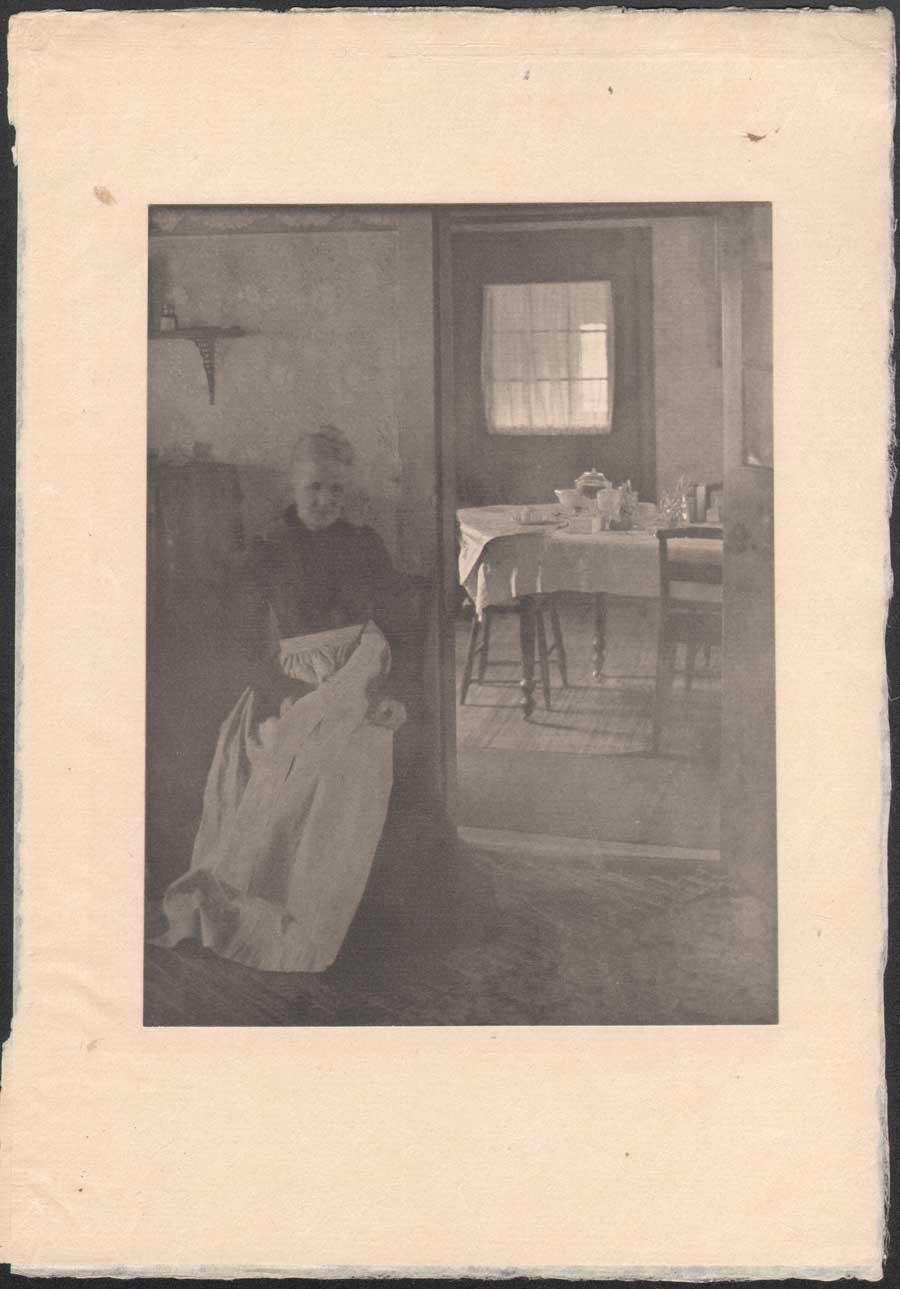

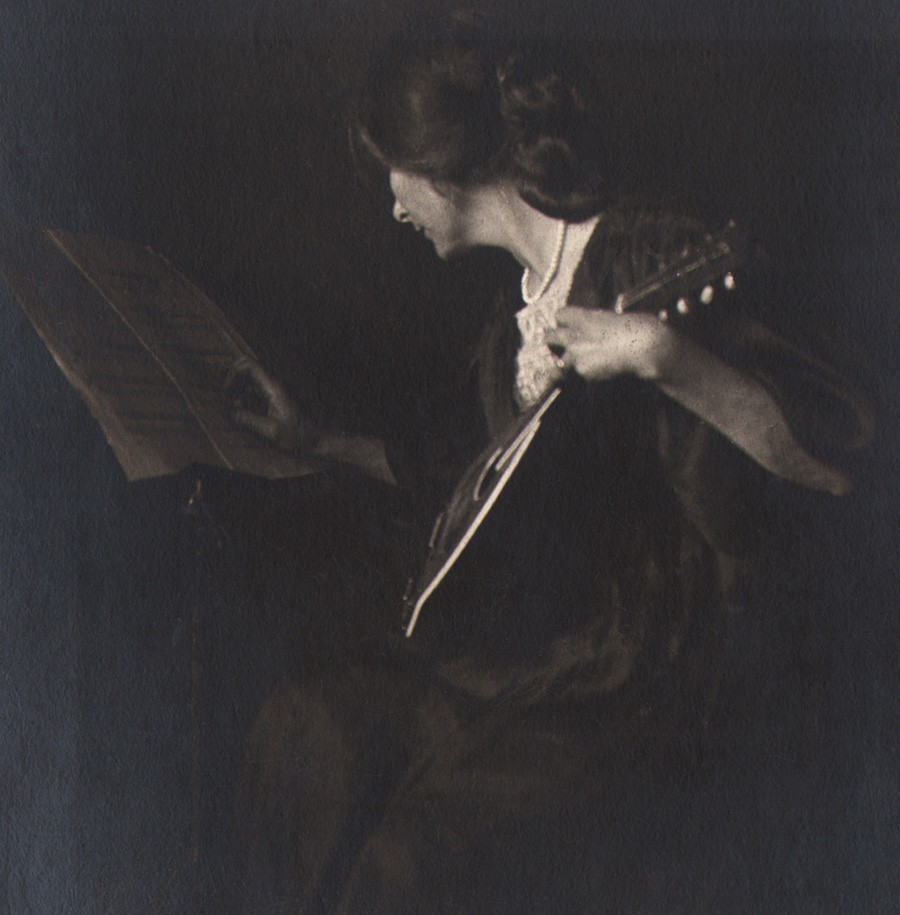

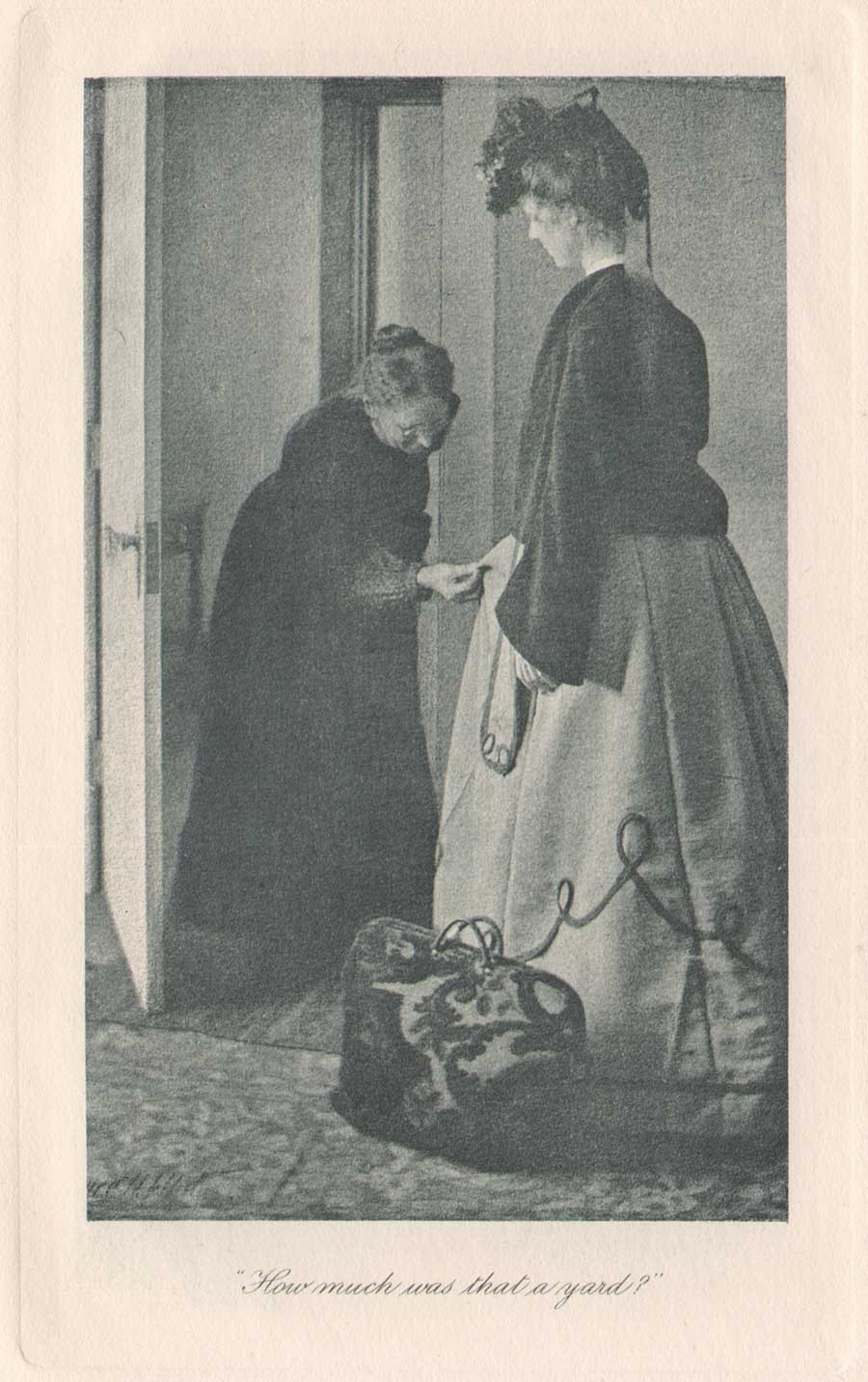

Detail: Clarence H. White: American: “How much was that a yard ?” Hand-pulled photogravure plate printed by John Andrew & Son (image: 12.2 x 7.5 cm | support: 20.0 x 14.0 cm ) from: Edition de luxe impression of Eben Holden: Lothrop Publishing, Boston: 1903. The Library of Congress states the model at right is Ann Fulton and the woman examining the dress is the photographer’s mother Phoebe Billman White (1845-1920) : from: PhotoSeed Archive

Knowing the book now existed in multiple impressions with the Clarence White photogravures was perplexing to me at first, but I’m certain the inclusion of the White photographs was intended by the publisher Lothrop for a more discriminating audience, so its assumed they had the monetary incentive to publish more than the one impression-even with the fickleness and extra work necessary to bind an edition with hand-pulled gravures.

To this end, my research in preparing this post discovered 1901 to be the year Clarence White was first commissioned by the Boston publisher to illustrate a new edition of Eben Holden. The intended publication date of very late 1902 was designed to coincide with the lucrative holiday sales season. Even with the move to e-books in our modern age, publishers earn good money issuing ornate and extra-illustrated editions during this time of year catering to the once a year book buyer and bibliophile alike.

Known as the Edition de luxe, this edition of Eben Holden with the White photogravures priced at $2.00 somehow managed to miss the late 1902 holiday sales season. The curious fact of the inclusion of the imprint for March 12, 1901 on the limitation page and White’s signature including the year 02 on many of the 12 plates in the published work was basic economics for publisher Lothrop-they simply used existing leaves, including the old limitation pages from current stock when it was eventually released for sale to bookstores in 1903.

Top: detail: 1896: advertisement for John Andrew & Son from the “Boston Blue Book”. (from: Hathi Trust) Bottom: detail: typical example of the firm’s engraved credit appearing at lower right corner of image margin on plate recto from the 1903 Photographic Times-Bulletin. The John Andrew firm was established in Boston in 1852. from: PhotoSeed Archive

This was by no means unprecedented by Lothrop, or other large publishing houses of the era, as they would have set aside a certain number of unbound sheets from a best-selling work for limited impressions featuring artwork. The first illustrated edition of Eben Holden featured halftone photographs taken by Joseph Byron from the Broadway production of the same name hadn’t even debuted until Oct. 28 of 1901. This also used the March 12, 1901 imprint date. Known as the Dramatic Edition, it was described in the trade monthly The Bookseller:

“An illustrated edition of Eben Holden has been recently published called the Dramatic edition. It contains seven pictures of the play as it appeared in New York and a fine portrait of the author.” (3.)

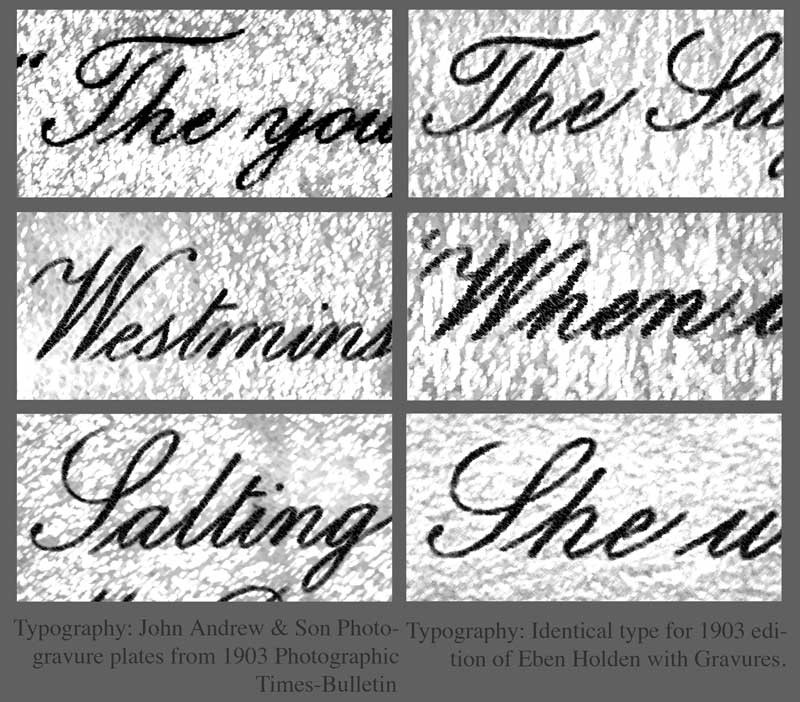

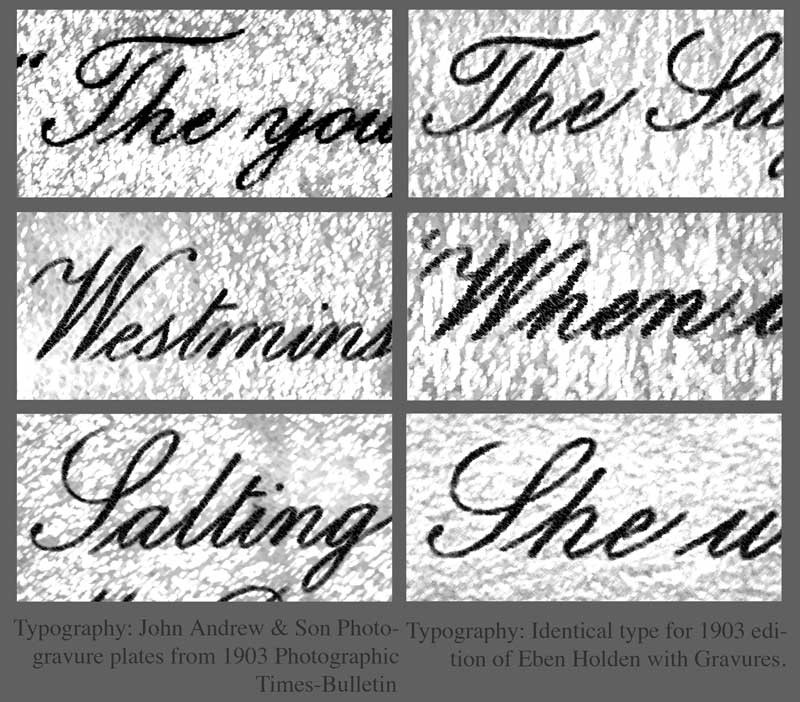

Details: with manipulations in PhotoShop to highlight typography: In order to show Boston’s John Andrew & Son atelier printed the photogravure plates uncredited in the de luxe edition of Eben Holden, it is useful to analyze the script font typeface used for photographic plate titles. Column at left, top to bottom shows known examples from the Andrew atelier taken from the 1903 Photographic Times-Bulletin. Column at right shows plate titles from the Eben Holden volume. all from PhotoSeed Archive.

Published in 1903

Finally, with the eventual tenth imprint of the fourth edition stating Two Hundred and Seventieth Thousand, September 18, 1903, (6.) the makeup of the Edition de luxe was that of a small 8vo Octavo instead of the common edition, a 12mo Duodecimo. The inclusion of 12 fine, hand-pulled photogravure plates by White seen here is another matter altogether. For one, other than White’s autograph-appearing often (and faintly) in the lower left hand corner of each plate image as CH White 02, the Edition de luxe neglects to give him any printed credit for the photographs nor the atelier who printed them. This is very surprising for a special edition. Typically, there would at the very least be a separate illustrations page noting titles and page numbers at the front of a similar volume, but for whatever reason they were not included.

Stieglitz plays Go Between

With Eben Holden’s great success, the dramatization of the novel on the Broadway stage was logical for its day-especially since the Cinema was not an option because of the infancy of the medium. Lothrop’s piggy-backing of the work through this Dramatic edition, even by the “flop” standard of 49 performances, was but one way of keeping the work “fresh”- even a full year after initial publication. At some point late in 1901, a result perhaps of someone seeing the play on Broadway or believing White’s work would lend itself nicely to a series of photographic illustrations, the Boston publisher-perhaps through an association with Fred Holland Day (who lived in nearby Norwood where the Norwood Press printed books for Lothrop) or Alfred Stieglitz in New York-gave White the commission for its second illustrated edition of the novel.

Clarence H. White: American: 1902: “She was still looking down at the fan”: vintage Platinum or gelatin silver print: Showing typical retouching by White, the models are Alfred Dodge Cole, (1861-1928) a professor of Chemistry and Physics at Denison University and his wife Emily Downer Cole. (1865-1957) They play the roles of William Brower and Hope, whom Brower eventually marries in the novel Eben Holden. The photograph was reproduced as a photogravure plate and included in the Edition de luxe. Curators at the Robbins Hunter Museum where this and other White photographs are held stated the photographer had taken family photographs of the Downer family on the lawn of the home in the late 1890’s and so he “would have been familiar with the house and furnishings from that commission. It was common for Clarence White to ask acquaintances to pose for photographs, often in costumes that he would provide. The photographs for Eben Holden were staged with costumes from the Civil War era.” Photograph courtesy: Collection of the Robbins Hunter Museum in the Avery Downer House, Granville, OH.

Ultimately, Stieglitz’s publishing background, connections and established relationship with White through his editorship of Camera Notes, his new involvement with Camera Work, as well as his having his own work exhibited in an early salon of pictorial photography in Newark Ohio in late 1900 and other exhibitions made Stieglitz a believer in White’s potential as an illustrator:

“What is especially fascinating, however, is what occurs when White is commissioned, as he was in 1901, to take up literary illustration himself. Through the assistance of Stieglitz, White received the commission to illustrate a new edition of the novel Eben Holden by Irving Bacheller. ( 4. )

And much later, the photographer’s grandson Maynard Pressley White commented about a bit of reluctance on his grandfather’s part in dealing with Lothrop as part of his Ph.D. dissertation in 1975:

“The correspondence with Stieglitz concerning the illustrations for Eben Holden is revealing of his character as well as Stieglitz informed him that he suffered from no such timidity and would–and indeed did–handle the matter with the publishers, as it turned out, to the advantage of White.” (5.)

Clarence H. White: American: 1902? : vintage untitled Platinum or gelatin silver print: The model Emily Downer Cole (1865-1957) poses wearing a different dress than seen in the published Eben Holden photogravure “She was still looking down at the fan” taken on the same settee in the front parlor of the Downer family home. This was likely an alternate study Clarence White took for consideration for his series of Eben Holden illustrations. Photograph courtesy: Collection of the Robbins Hunter Museum in the Avery Downer House, Granville, OH.

John Andrew & Son: founded in Boston: 1852

In giving credit to White and the firm that printed his photographs as gravures, a bit of elucidation seems in order to set things straight. Upon close inspection of these plates along with many others by Boston’s John Andrew & Son from the same time frame, I feel confident giving the Andrew firm credit for printing them. This is based on a near exact match in the script font used for the plate titles in the de luxe edition of Eben Holden as well as those plates credited to the firm appearing in the Photographic Times Bulletin from 1902-04.

I’ve included examples of the font as a comparison with this post. Another exact match is the same plate paper was used for both publications: this is very revealing especially on the plate verso where a very fine stipple pattern can be seen on the paper surface of the cream-colored plate paper. Perhaps the strongest association with the John Andrew atelier and the Norwood Press (which printed the de luxe edition) emerged in my research on business associations with some of the individual companies that came together in 1894 when that press was formed. These included J.S. Cushing & Co., (for composition and typesetting) Berwick & Smith Co., (for presswork) and E. Fleming & Co. (for binding). Beginning around 1890, all of these firms along with John Andrew were under one roof as part of the brand new Dana Estes & Company publishing house buildings on Summer Street in Boston.

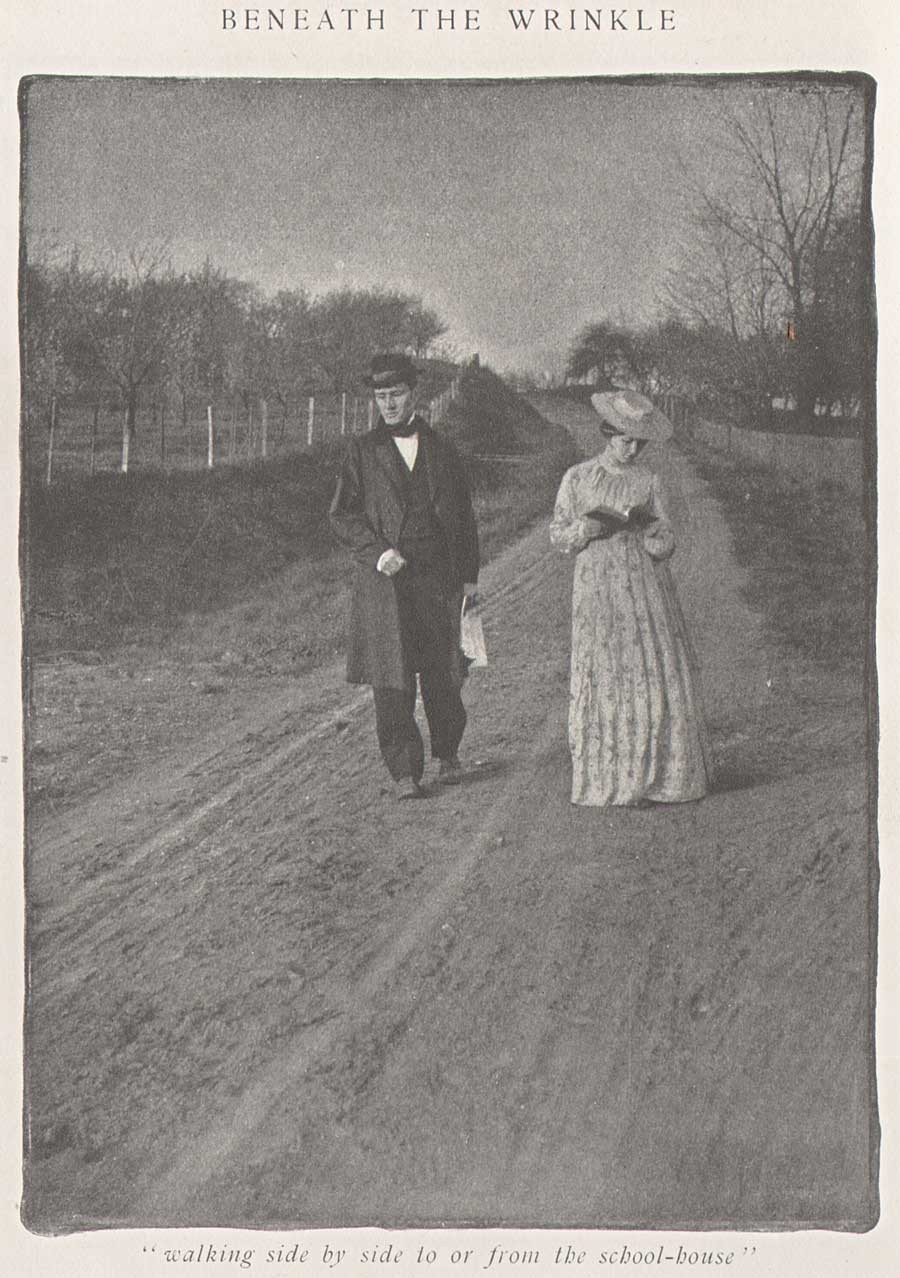

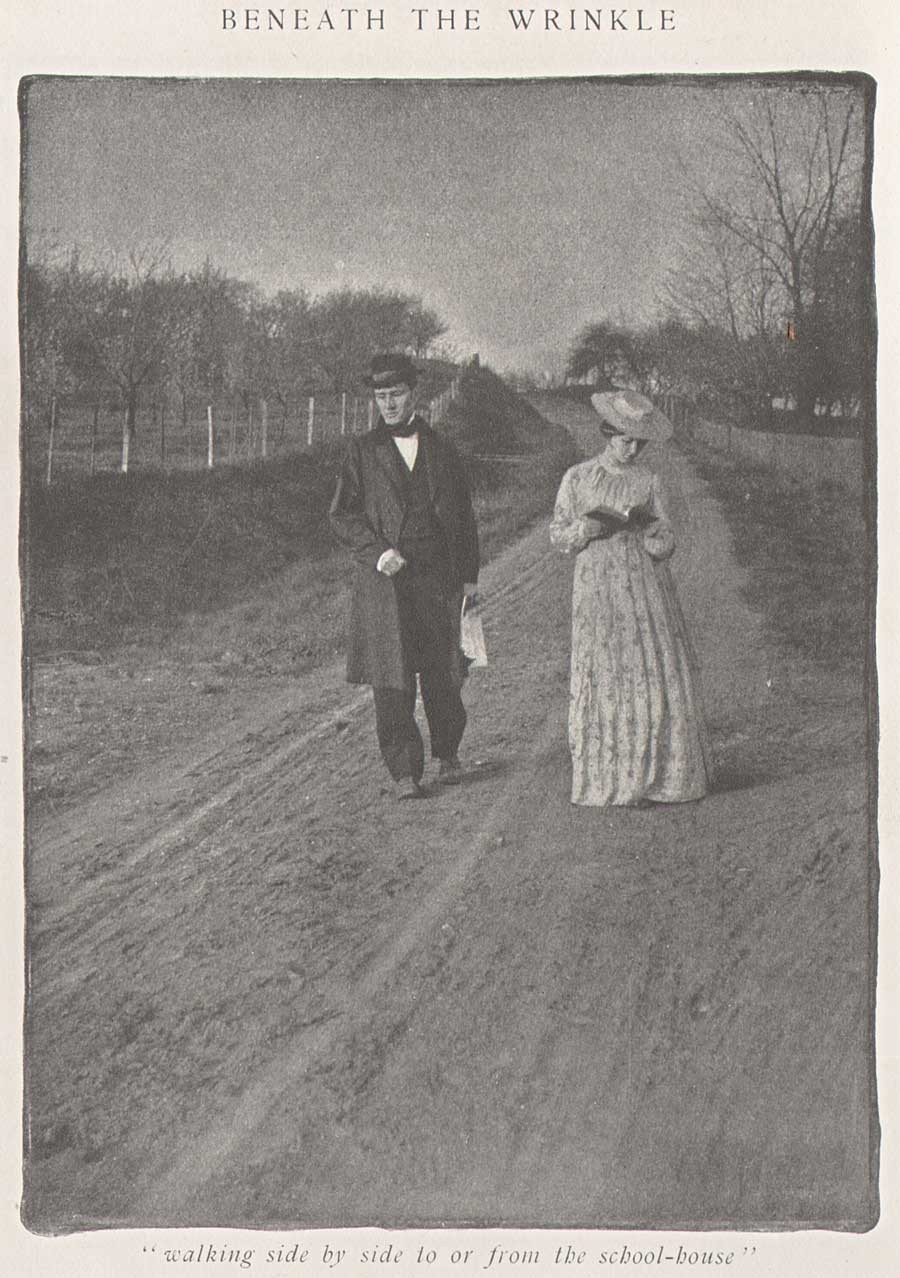

Clarence H. White: American: 1903: halftone: “Walking side by side to or from the school-house” was one of three photographs published to illustrate the Clara Morris story “Beneath the Wrinkle” published in the February, 1904 issue of McClure’s Magazine. (12.8 x 9.5 cm) published: p. 430. From: PhotoSeed Archive

With the move to Norwood in 1894, the Andrew atelier stayed behind in Boston at 196 Summer St. but continued to provide fine photo engraving work to the major publishing houses in Boston and New York. Known today for printing many of the photogravure plates beginning in 1907 for the monumental Edward Sheriff Curtis work The North American Indian, the firm sometime in the first decade of the 20th Century became a department of the Suffolk Engraving & Electrotyping Co. of Boston with offices at 394 Atlantic Ave.

Named after John Andrew, (1815-1870) a wood engraver born in England who immigrated to Boston where he worked with fellow engraver Andrew Filmer, the firm eventually made the transition to photo engraving, including the half tone and photogravure processes. Andrew’s son George T. Andrew succeeded his father at the business, located at 196 Summer St. An 1892 overview of the firm from the volume Picturesque Hampden gives some background:

JOHN ANDREW & SON COMPANY.

ENGRAVERS AND MAKERS OF FINE BOOKS, BOSTON MASS.

If we go back a few years, we find that in illustrating books and magazines wood and steel engraving were about the only methods available. Nor could steel engraving have any wide use on account of the great expense of printing. Ever since its start, in 1852, the firm, now styled the John Andrew & Son Company, has held a prominent place among illustrators, especially in work of the finest grades. Their reputation was made in the first place as engravers on wood, but the discovery of delicate chemical and mechanical processes has in later years led them to also take the photo-engraving and half-tone work which has at present such wide use and popularity. In this field they do work for some of the best magazines and books published in this country. In what they undertake they strive not so much to do the cheapest work in price as the best work in quality. Quite recently the firm has taken up the photo-gravure process in addition to those spoken of above. The industry we describe is not located in Hampden county, but the mention here is not inappropriate as the engraving of our pen and ink pictures was done almost wholly by this firm. Their address is 196 Summer street, Boston.

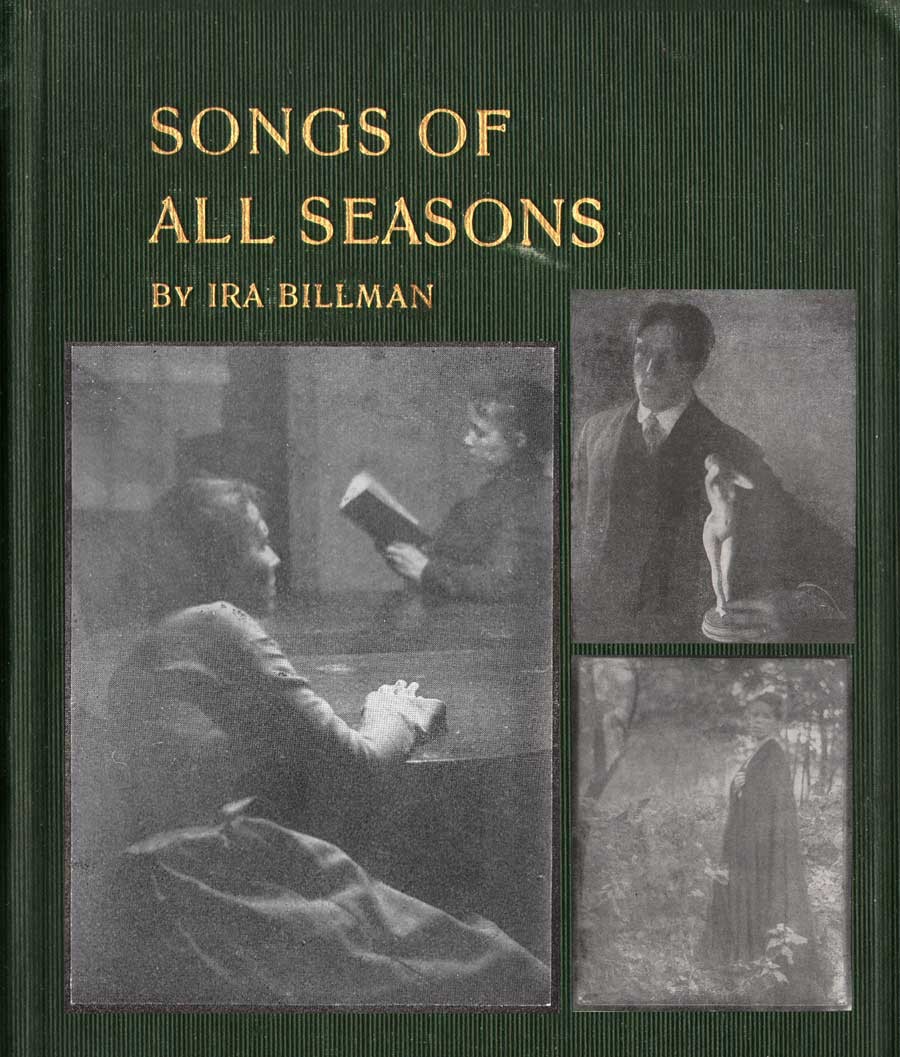

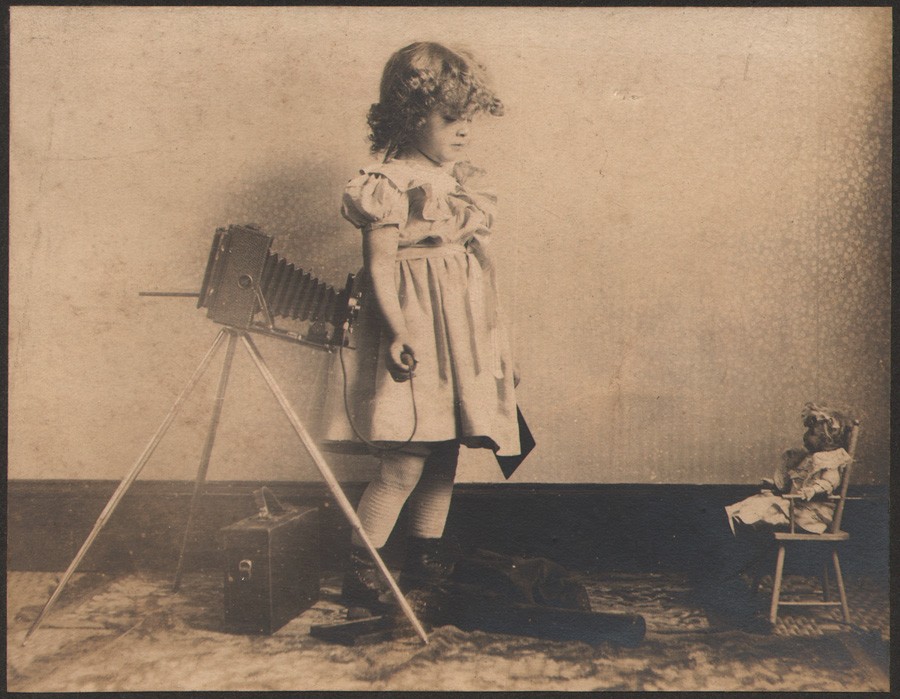

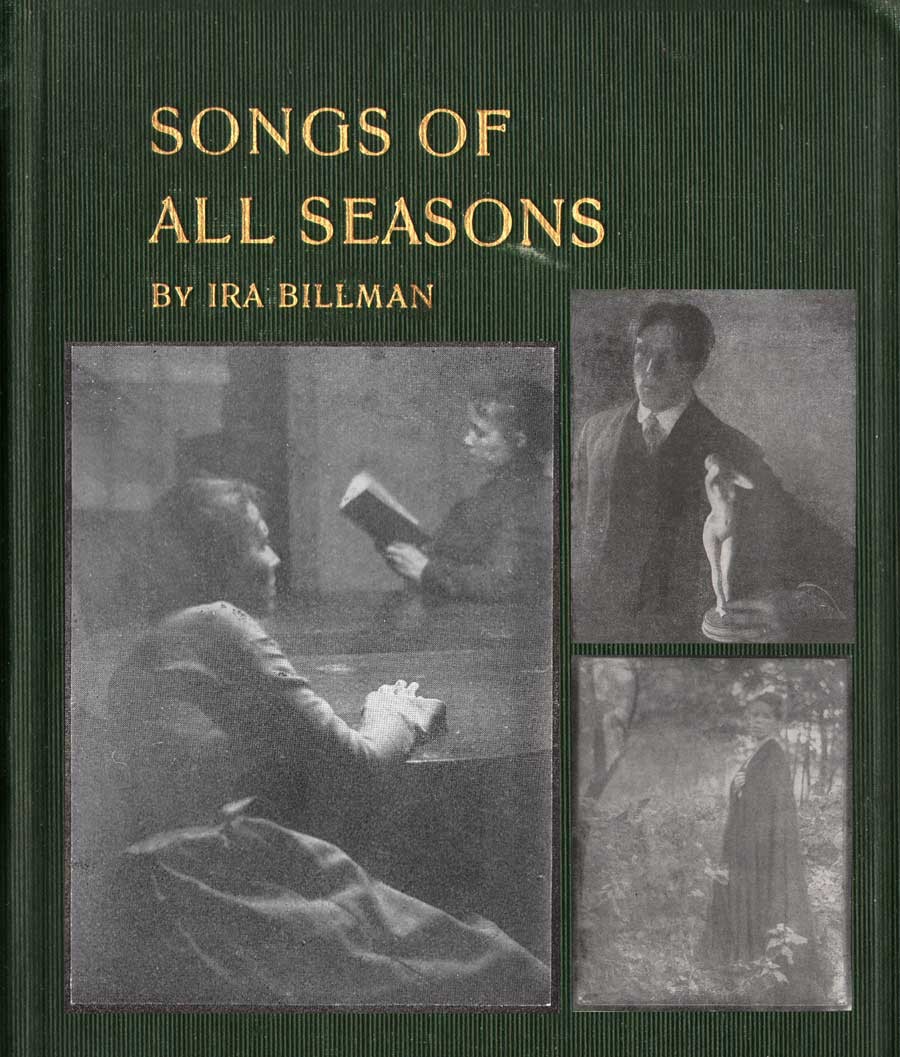

Detail: Cover for “Songs of All Seasons” by Ira Billman. The Hollenbeck Press, Indianapolis: 1904. Gilt-engraved stamped cloth: 20.4 x 13.6 cm: shown inset with representative photographs taken by Clarence White reproduced in halftone in the volume. Photo left: “The Book Lovers” (p. 181); top right: untitled man with statuette illustrating poem “The Twin Flower” (p.137); bottom right: “The Gloaming” (p. 199). Billman was Clarence White’s uncle and was “one of his earliest artistic influences in his life”: From: PhotoSeed Archive

Photographic Illustration: a New Outlet

A newspaper clipping, believed to be from the Newark Daily Advocate in the Clarence Hudson White clipping file at the Newark, OH public library, includes the following undated (but 1903) story discussing Eben Holden in passing while concentrating on a new commission that inevitably came from it: costume-piece photographs by White similar to those he did for Lothrop for author Clara Morris’s story published in McClure’s magazine in February, 1904 entitled “Beneath the Wrinkle“:

PICTURES From Real Life by Clarence White

Forwarded On Order to a New York Magazine-Local Artist’s Latest Work.

Mr. Clarence White received a command last fall from the art department of McClure’s Magazine to illustrate Clara Morris’ new story, entitled, “Beneath the Wrinkle,” that will appear in that magazine presumably in the near future. Mr. White was to have been given all the time he wanted, but in view of the change of art editors, Mr. White was notified about three weeks ago that the illustrations would be required immediately. Mr. White at once notified the publishers that he would use all his efforts to complete them immediately, and would forward them when completed. Today the set comprising six, were forwarded and as equaly as clever and well executed as the ones made for the illustrating of the holiday edition of Eben Holden that was to have made its appearance last Christmas, but was not completed in time for that season. The ones now in progress are all local personages, done in quaint, old-fashioned garb and surroundings, recalling vividly to mind the characteristics in dress and decorations then in vogue. They show the fine and beautiful artistic temperament of Mr. White in his striking correct interpretation of dress and customs of the period in which the characters live. Mr. White deserves the honor the illustrations will surely bring to him, as he is always conscientious and painstaking in whatever he undertakes in his profession.

Left: Irving Bacheller, (1859-1950) American journalist and author, wrote the novel Eben Holden which sold over 1 million copies. This portrait with facsimile autograph by an unknown photographer appeared as the frontis (13.3 x 9.1 cm) to the Dramatic Edition of the book-the first illustrated edition featuring photographs of the Broadway stage production that debuted Oct. 28, 1901 and ran for only 49 performances. Right: ” ‘Fore your other arm gits busy, wont you wind the clock?” (14.1 x 8.4 cm) Actor E.M. Holland at left plays the role of Eben Holden, Lucille Flaven plays Hope and Earle Ryder as an American Civil War officer plays William Brower. The important New York commercial photographer Joseph Byron, (1847-1923) founder of the Byron Company (currently, the 7th & 8th generations runs Byron Photography) took stage photographs of the play at New York’s Savoy Theatre with plates published in the Dramatic Edition. from: PhotoSeed Archive

White Family Connections: Songs of all Seasons

During the time he received the commission for illustrating Beneath the Wrinkle in 1903, a more intimate family connection developed which allowed White the opportunity to take another series of photographic illustrations, 42 in all, published in 1904 within a slim volume of poetry titled Songs of All Seasons.

The author was nationally known poet Ira Billman, Clarence White’s uncle, the brother of his mother Phoebe Billman White. In the volume Symbolism of Light: The Photographs of Clarence H. White published in 1977 which accompanied an exhibition of White’s work at the Delaware Art Museum and International Center of Photography, White’s grandson Maynard P. White, Jr. describes Ira Billman as a major influence on Clarence and Songs:

Among the gathering of aunts and uncles that gave meaning and context to the artist’s early life was Ira Billman, his mother’s brother. “Poetic” is the word most often used to describe White’s photography, and his Uncle Ira, a poet by avocation, was one of the earliest artistic influences in his life. …Billman’s work celebrates rural America; his poems are songs to people and to nature, and they are imbued with the deep religious sentiments of his Lutheran heritage, without being mawkish or even faintly cloying. What is important for the purpose of my discussion is that Clarence White made the photographic illustrations for Songs of All Seasons, and Billman dedicated the volume to him. (7.)

“To Governor John A. Dix with many good wishes from Uncle Eb an’ me Irving Bacheller N.Y. Feb. 22 1911.” This personal inscription by Bacheller to John A. Dix, then Governor of New York State, appears in a volume of Eben Holden with the imprint of Two Hundred and Seventieth Thousand, September 18, 1903, the actual year the novel was released for sale. In a 1901 newspaper article, Bacheller said the character Eben Holden was based on “a composite of my father and his hired man-a very jolly old fellow”. from: PhotoSeed Archive

Ninety-one poems and sonnets are included in the volume. Here, The Test, a representative poem from the work:

The Test

Not what I felt will be the test

When song and fragrance filled the hour,

And all the sunshine of the blest

Unfolded me to perfect flower.

Not what I aid will be the test

When by sweet waters wound my way,

And white-haired, thoughtful hills all guessed

The word I was about to say.

Not what I did will be the test

When stunned by cry of human needs

I dreamed I was myself oppressed,

And woke to passion of great deeds.

Not what I chose will be the test

When first I saw one world in hand

Is worth two in the bush-the best

Of which it is to understand.

O! none of these will be the test,

But what God knows I would have done,

Had I been nurtured in the nest

Of one, I now condemn and shun. (8.)

Left: Clarence H. White: American: 1902: hand-pulled photogravure: (9.7 x 7.3 cm) in: Eben Holden: A Tale of the North Country: Boston: Lothrop Publishing. (1903) Appearing as the frontis portrait in the Edition de luxe, this unknown subject was the novel’s namesake: a fictional character who was a former farm-hand and main father figure for the newly orphaned William Brower serving as the narrator in the work. Right: Clarence H. White: American: 1902: halftone: (12.0 x 9.2 cm) in: Eben Holden: Harper & Brothers Publishers. (1914) Part of the Pine Tree Edition of Irving Bacheller’s (Collected) Works. This heavily manipulated portrait from the original photograph by Clarence White of Eben Holden published 11 years earlier also appeared as the frontis for the first volume in the Pine Tree series. From: PhotoSeed Archive

Pictorial Illustration for Photography a Growing Field

By 1904, esteemed critic Sadakichi Hartman, writing in Leslie’s Weekly, weighed in on the growing use of photography for book illustration:

“…and Clarence H. White, of Newark, O., has found a new opening for photography in the illustration of books. His illustrations for “Eben Holden” have attracted wide and deserved attention.” (9.)

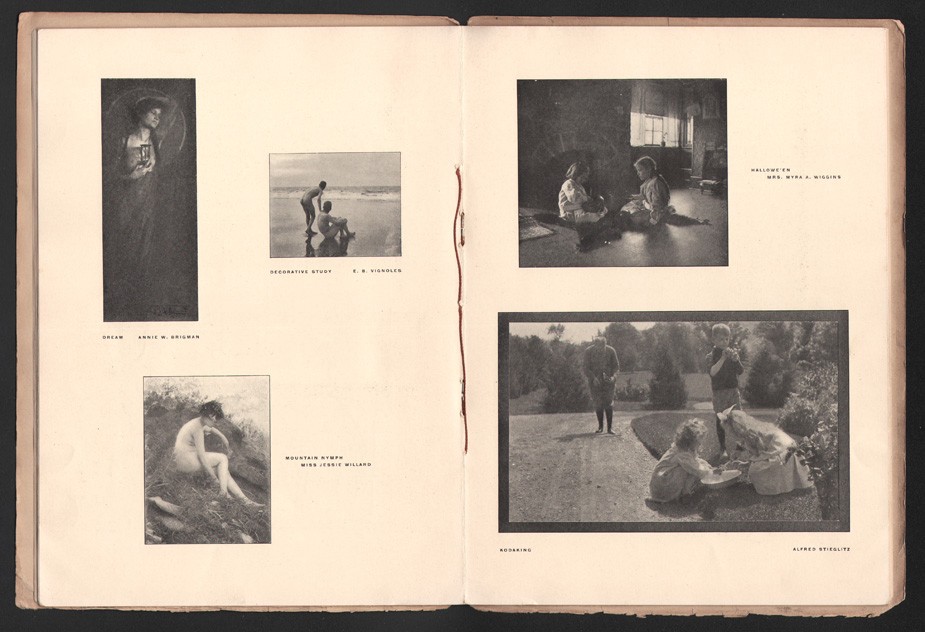

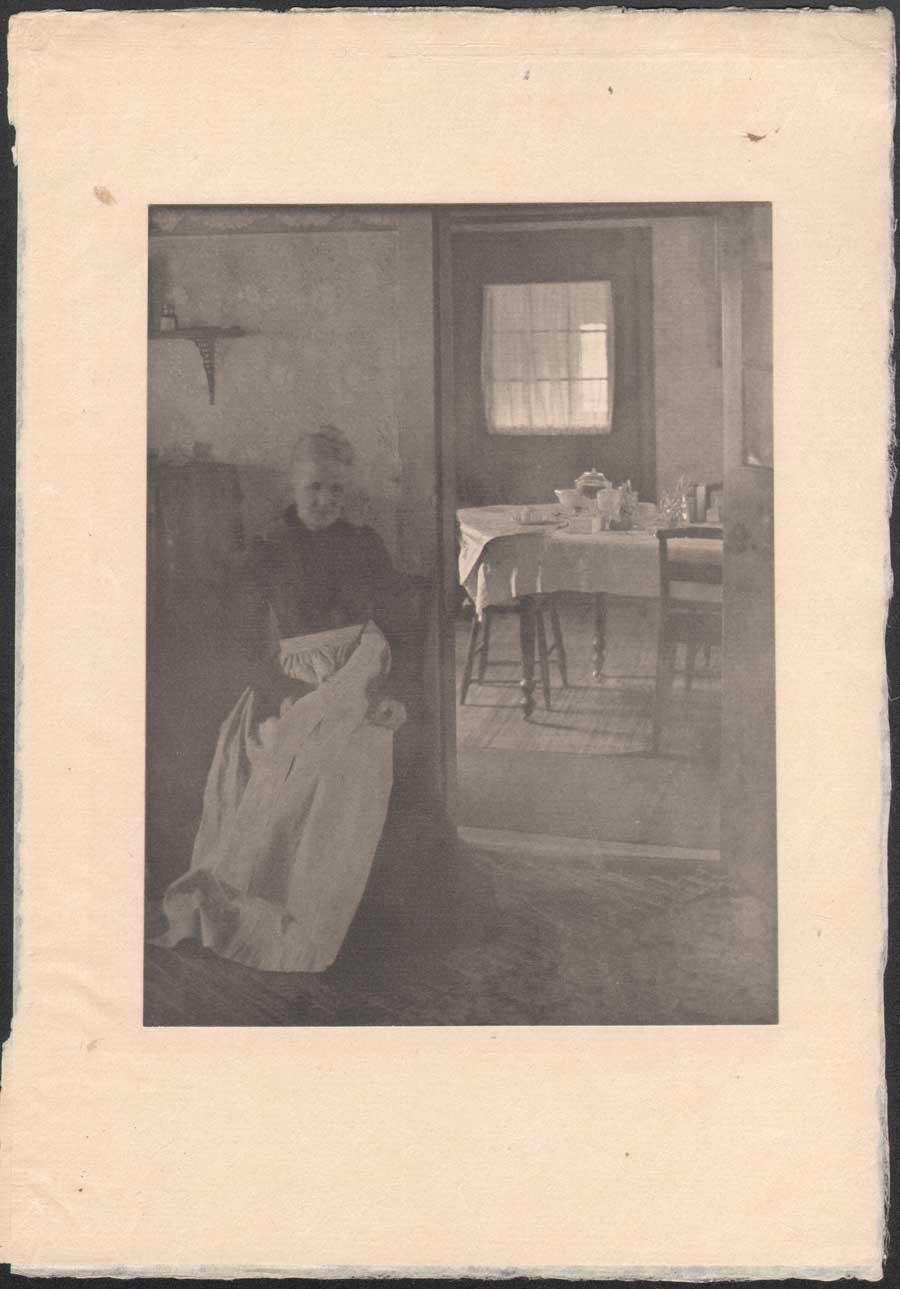

Clarence H. White: American: 1902: “Illustration to “Eben Holden”” (1903) hand-pulled photogravure: (tipped image:19.7 x 15.0 cm | Japan paper support: 30.5 x 21.0 cm) in: Camera Work III. (1903) Two plates in the Edition de luxe of Eben Holden: “How much was that a yard ?” (seen in this post-CW IX: 1905) and this one: “Mother was living in the old home alone”-an interior portrait of the photographer’s mother Phoebe Billman White (1845-1920) were also published as photogravures in Camera Work. From: PhotoSeed Archive

And later that year, citing White’s involvement with Eben Holden while writing in the Photographic Times Bulletin, Hartman brought up the potential financial rewards possible for pictorial photographer in this new field:

“The only way to approximate a market value of pictorial prints is to investigate how much they might bring on the average, if offered for sale as illustrations. There is lately a decided demand for photographic illustrations, and consequently a certain standard price in vogue. The pictorialist, of course, and perhaps with some right, aspires to illustrator’s prices (i.e., $50-$100 for the full page of a magazine), but he has never reached it, with the one exception of Clarence H. White, who is said to have received several hundred dollars for his series of “Eben Holden” illustrations.” (10.)

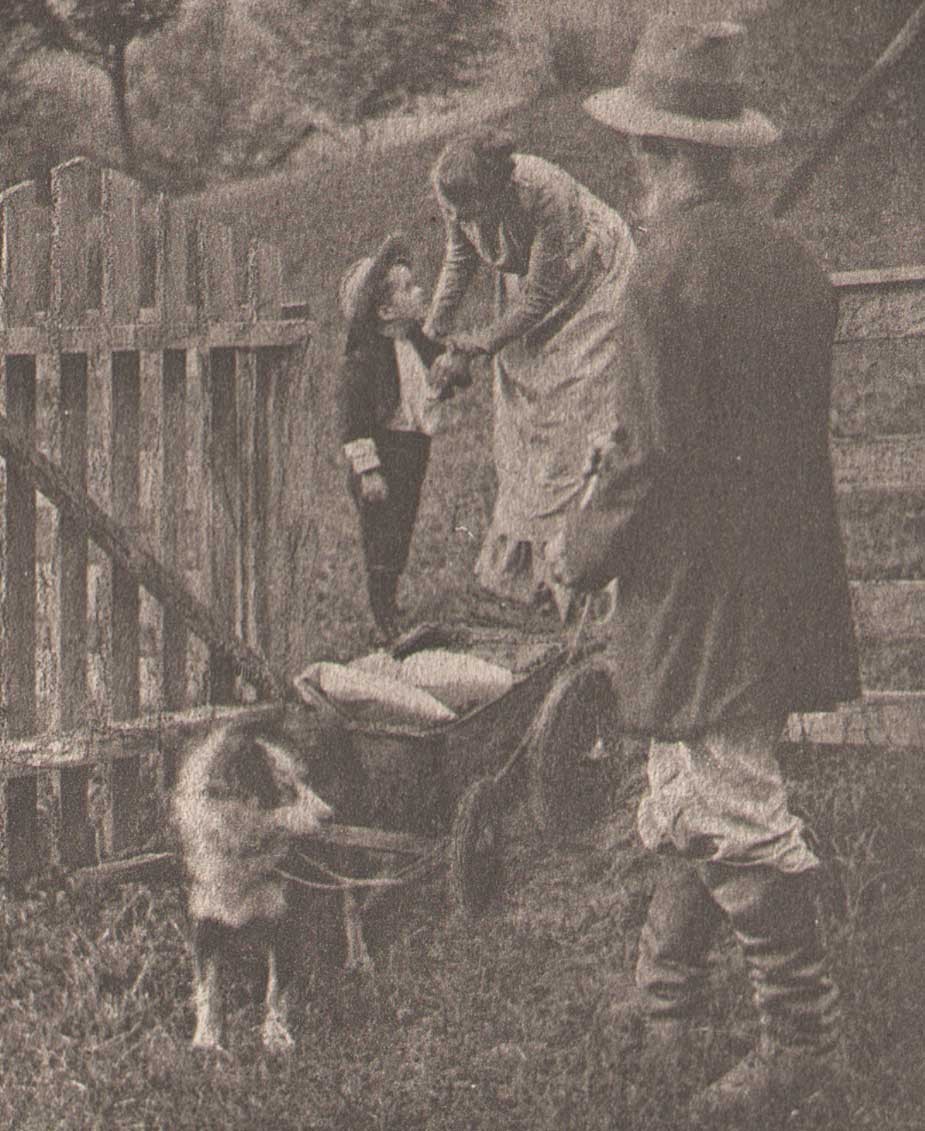

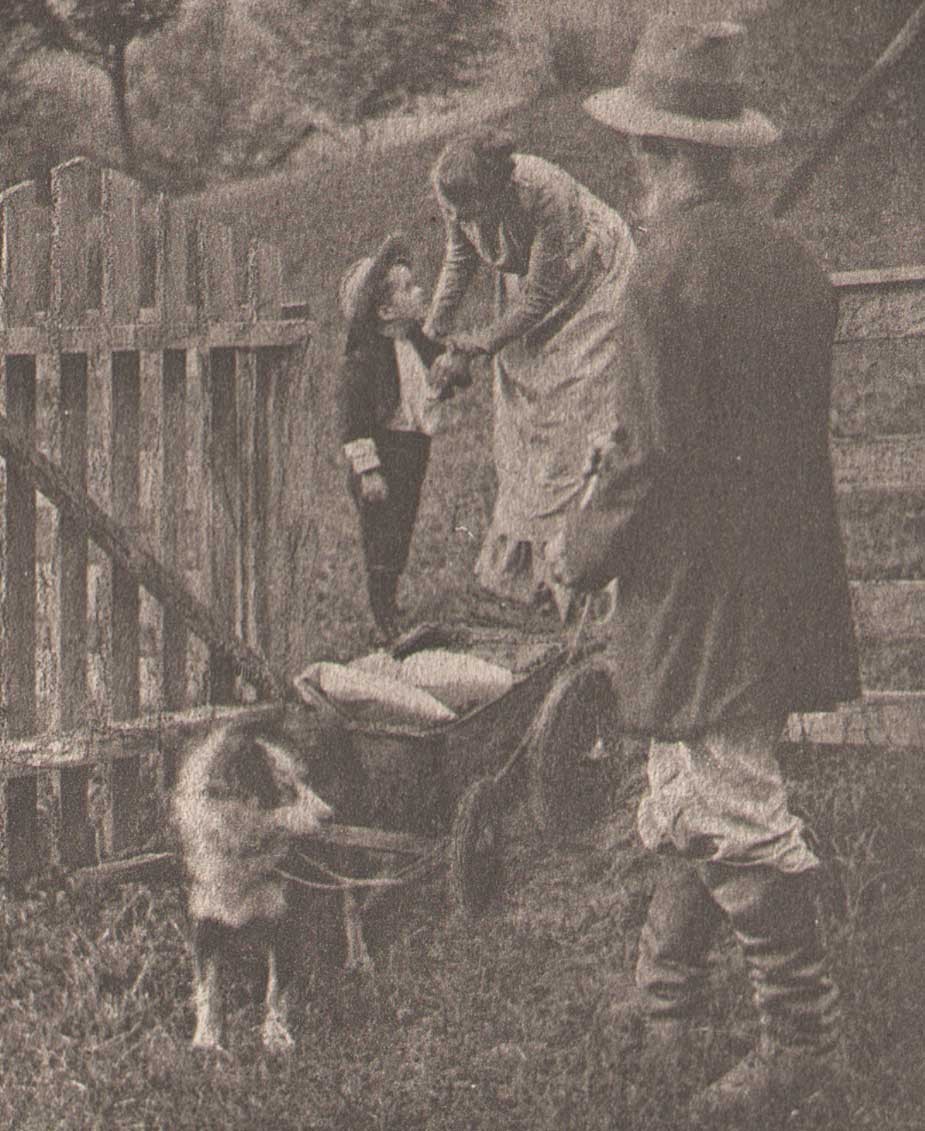

Detail: “Tucked some cookies into my pocket” : Clarence H. White: American: 1902: hand-pulled photogravure plate (11.9 x 7.3 cm) included with Edition de luxe of Eben Holden (1903): Lothrop Publishing, Boston. The young orphan William Brower is possibly modeled here by the photographer’s son Maynard Pressley White (b. 1896) and his wife Jane Felix. (1869-1943) The scene shows Brower preparing to head out into the wilderness in a dog-pulled cart with Eben Holden at right. From the novel: “Our hostess met us at the gate and the look of her face when she bade us good-by and tucked some cookies into my pocket, has always lingered in my memory and put in me a mighty respect for all women.” From: PhotoSeed Archive

This additional source of significant money to Clarence White and his young family through these illustration commissions invariably gave him additional confidence in his abilities as a photographer and financial peace of mind to eventually make his way to New York City, leaving Newark in 1906. It is also not a stretch to infer White’s own life mimicked the storyline of hard work that can earn the “American Dream” found between the pages of Eben Holden. Although the critic for the New York Times reviewing the play at New York’s Savoy theater didn’t care too much for the acting:

“As an exhibition of dramatic craft “Eben Holden” is hardly worth serious consideration“…

he did, a few paragraphs later, write the production had a few redeeming qualities:

But, despite its defects, the play is wholesome; it is redolent of the woods and the fields, and it provides the opportunity for an evening of entertainment that need not be looked back upon with regret. (11.)

No doubt Clarence White, had he been in attendance watching the play inside Newark’s Auditorium that 1904 November evening, would have agreed with these last sentiments of the big city critic, marveling and grinning to himself in the darkened hall while taking in the surreal juxtaposition that art imitating life can bring about.

Notes:

1. (White, Clarence H.) excerpt: An Annotated Bibliography on Pictorial Photography: Selected Books from the Library of Christian A. Peterson: Laurence McKinley Gould Library: Carleton College: Northfield, Minnesota: 2004

2. ABE listing: 120407. Besides multiple copies held by PhotoSeed, other known copies are in the Library of Congress, MOMA and Photogravure.com.

3. The Bookseller–Devoted to the Book and News Trade: Chicago: January, 1902: p. 28

4. Peter C. Bunnell: Inside the Photograph: writings on Twentieth-Century Photography: Aperture Foundation: 2006: p. 47

5. Clarence H. White : a personal portrait: Maynard Pressley White: Ph.D. dissertation, University of Delaware, 1975: pp. 79-80

6. see Beaumont Newhall’s Photography: A Short Critical History, from 1938, lists Eben Holden with the White illustrations as being published in 1903 on p. 215

7. excerpt: see Symbolism of Light: 1977: p. 7

8. Songs of All Seasons: Ira Billman: Indianapolis: The Hollenbeck Press: 1904: p. 65

9. excerpt: Advances in Artistic Photography: Sidney Allan: in: Leslie’s Weekly: April 28, 1904: New York: p. 388

10. excerpt: from: What is the Commercial Value of Pictorial Prints?: Sidney Allen: in: The Photographic Times Bulletin: December, 1904: p. 539

11. excerpt: review: “Eben Holden” at the Savoy: The New York Times, October 29, 1901