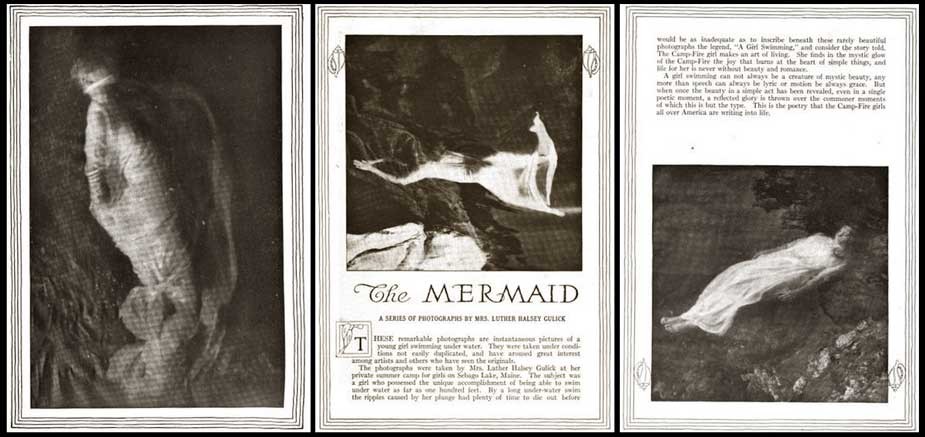

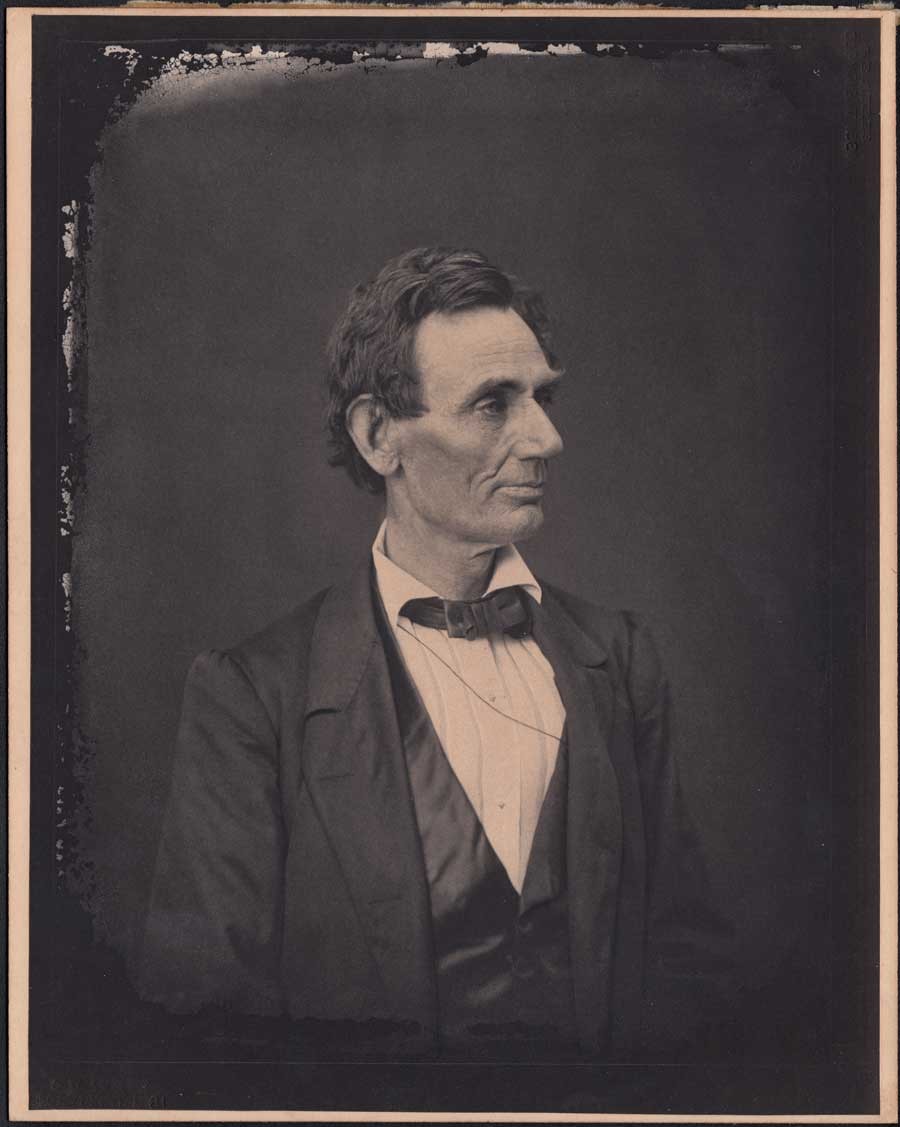

By all accounts, Scotsman David Octavius Hill, (1802-1870) Secretary of the Royal Scottish Academy of Fine Arts in Edinburgh, was an accomplished landscape painter. Thankfully, for the nascent medium of photography beginning around 1843, he is not remembered for that. Blame the Disruption, if you will.

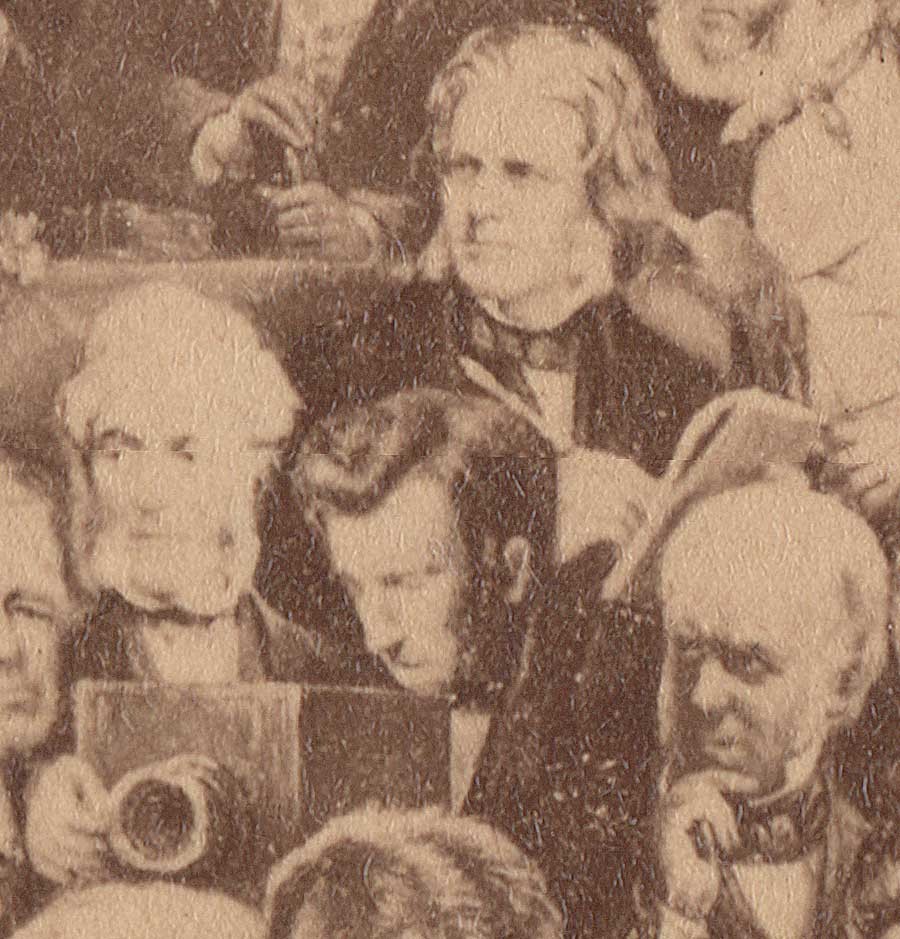

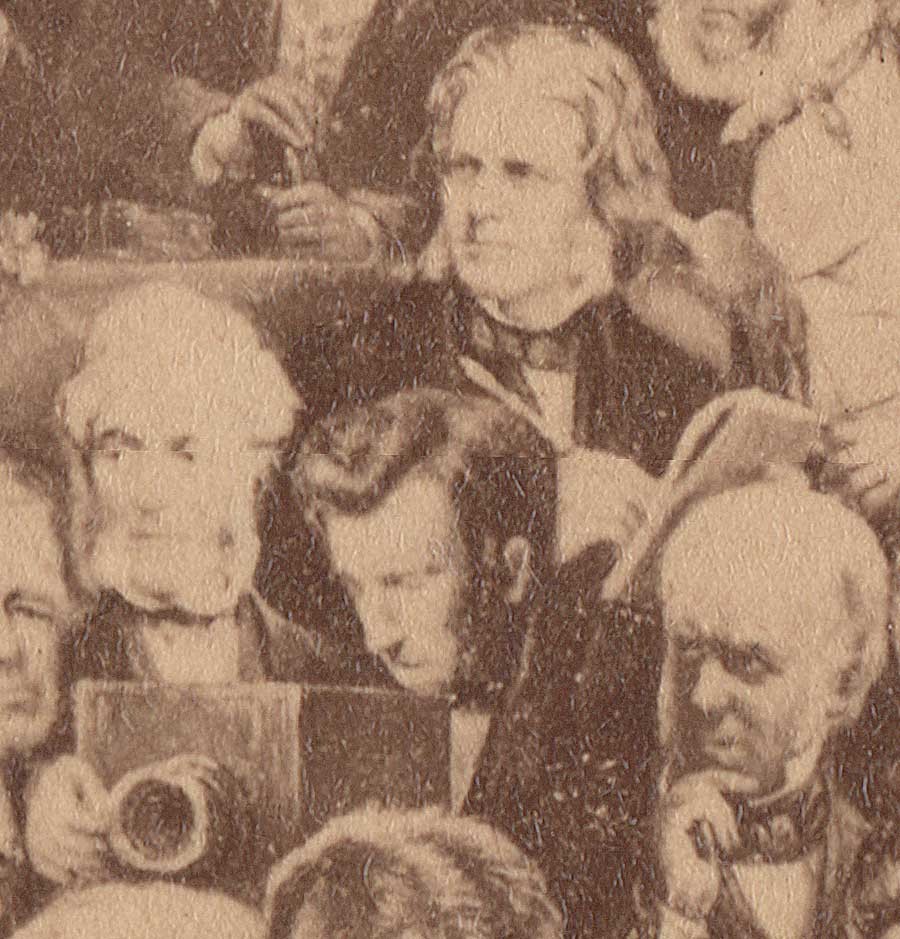

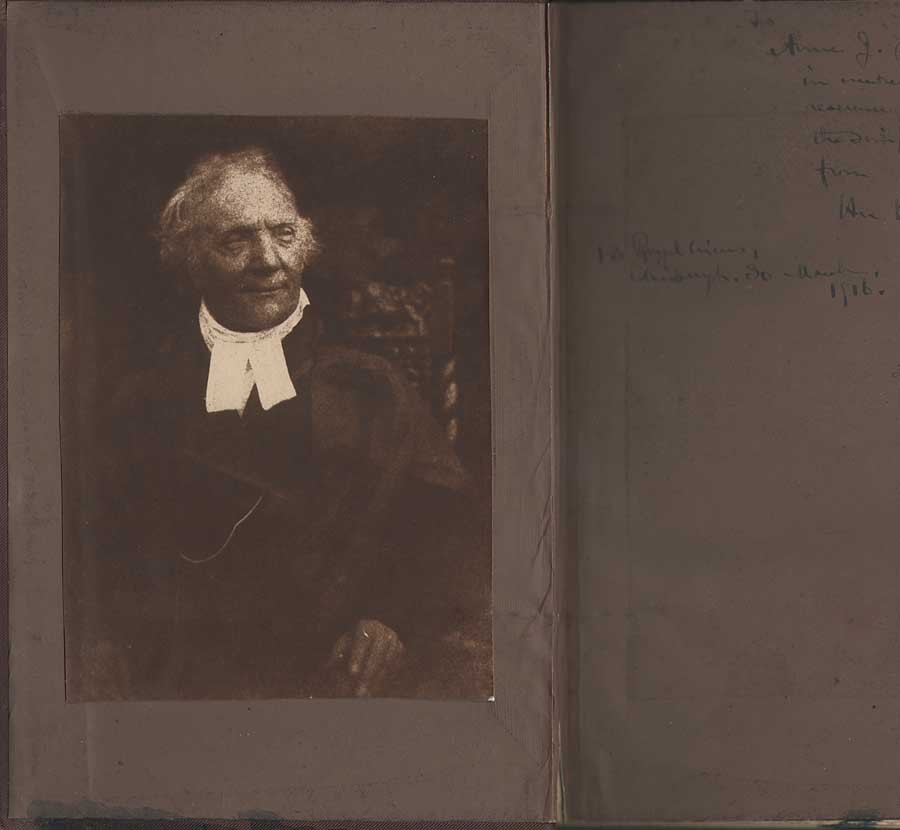

Detail: 1868: Artist David Octavius Hill with sketchpad at top; Photographer Robert Adamson behind wooden box camera at bottom. : Thomas Annan: vintage carbon copy photograph after D.O. Hill painting: “The Disruption of the Church of Scotland”completed 1866: original: (13.5 x 31.4 cm | 34.4 x 41.4 cm ) : from: PhotoSeed Archive

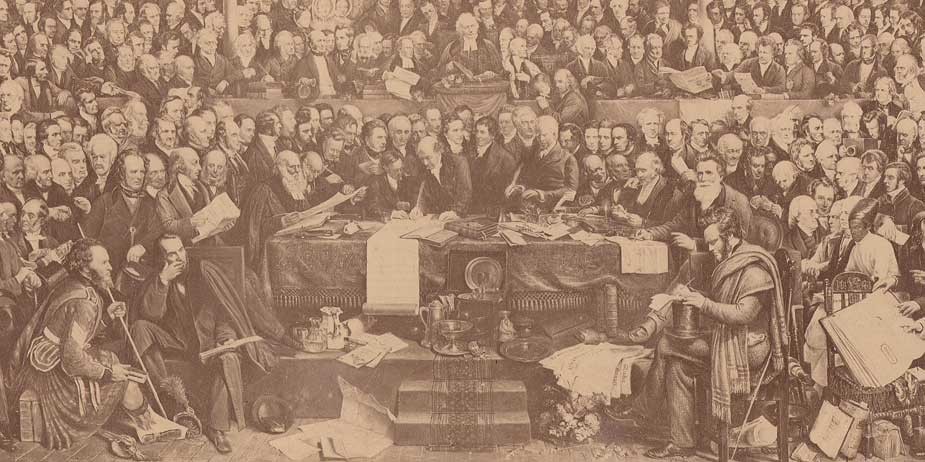

Disruption with a capitol D? He didn’t know it at the time, but when the freethinking Hill, a devout churchman seen above in detail in his own painting, sketchpad in hand, attended what became known as the Disruption: or, the historical occasion of Scottish religious free will known as the First General Assembly of the Free Church of Scotland signing the Act of Separation and Deed of Demission at Edinburgh’s Tanfield Hall, the artistic potential of photography would soon stake its’ own claim among the arts.

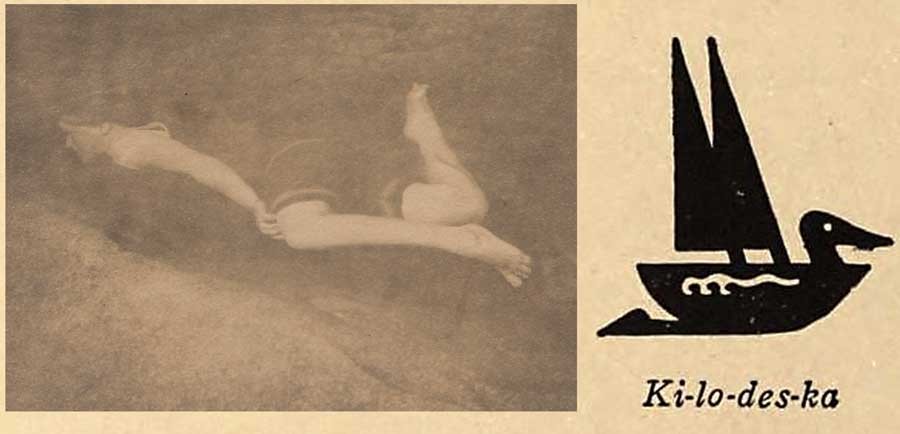

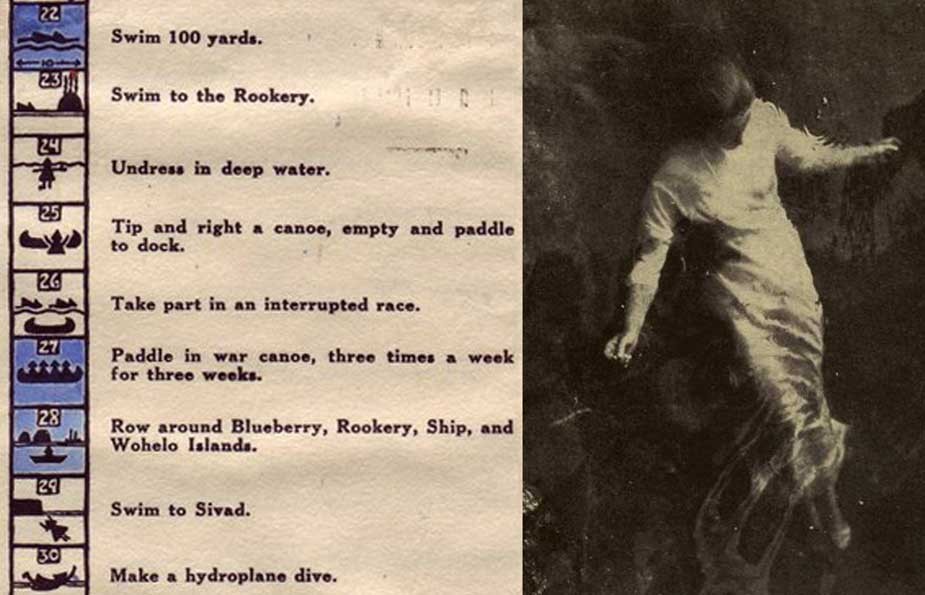

The Scots are Coming

Admittedly, the focus of this website doesn’t claim any great insights into the evolution of early photography, with the exception that certain photographers, those being the team of Hill and fellow Scotsman Robert Adamson, (1821-1848) popularly known as “Hill & Adamson”, are profoundly important to our understanding of artistic developments in relation to photography that came later in the 19th Century. Similar to the concept of how precedent by itself can build a case in the courtroom or in the more democratic court of public opinion, the reach of Hill & Adamson through their artistic achievement, especially in portraiture, impacted greatly the later working methods of many photographers and in particular, the eventual achievement of two fellow Scots who came into their orbit: Thomas Annan and his son James Craig Annan beginning around 1865 and in the early 1890’s.

As for that “Disruption” in relation to Hill’s completion 23 years later of an over-sized painting commemorating the event, the decision to separate from the accepted order gave former Church of Scotland congregations the freedom from central Church control to choose their own ministers, among other religious freedoms. For this alone, photography’s potential was nicely summed up in the London Art-Union journal in late 1869:

To photography Mr. Hill, soon after its discovery, about the year 1843, gave much attention, and we shall not be wrong in assigning him the credit of giving to the process its first artistic impetus; and, in conjunction with his friend, Mr. R. Adamson, of having produced many specimens of the Talbotype as yet unsurpassed for high artistic qualities. (1.)

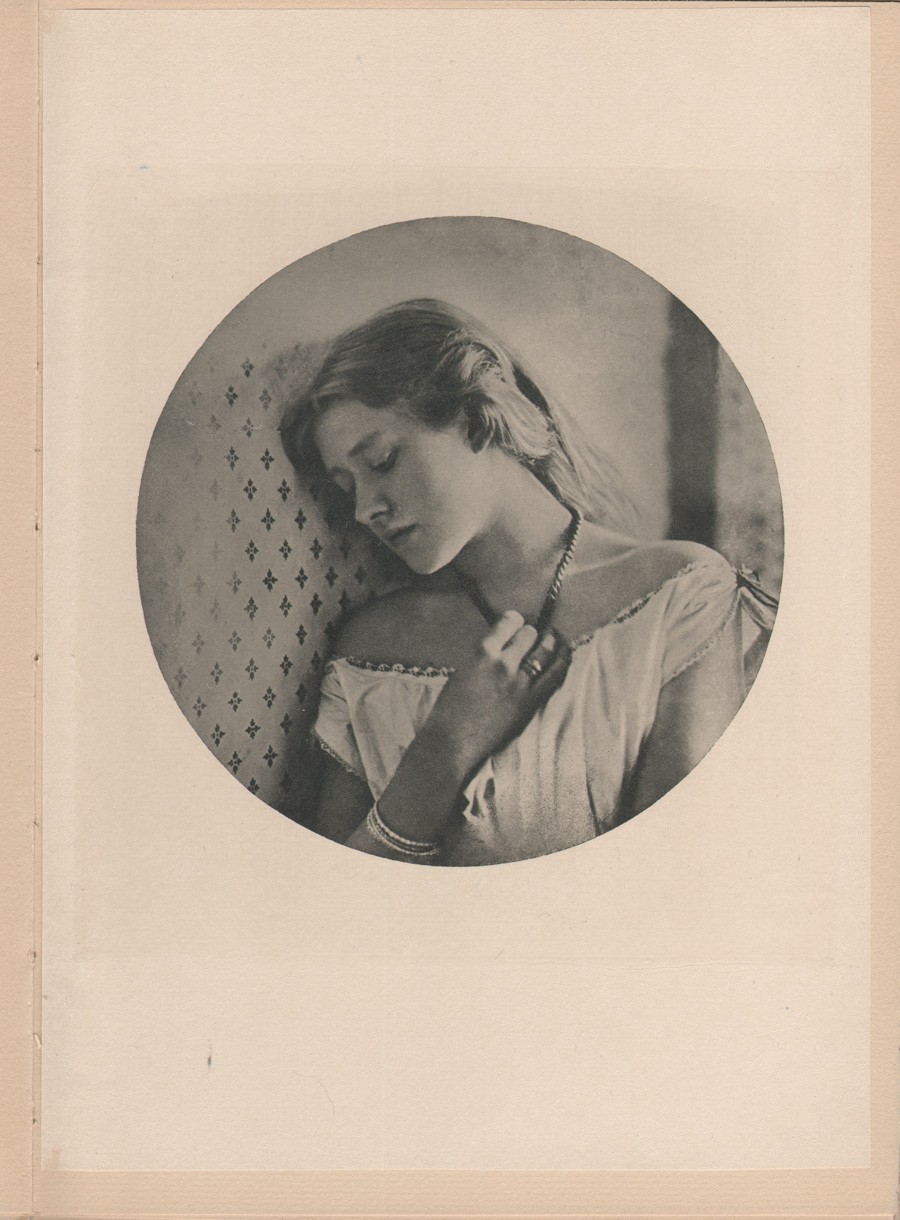

Example of vintage mounted salt print from calotype negative:(trimmed) : ca. 1845-1855: unknown photographer and location: detail from facade of English or Continental church building: ca. 1845-55: 12.8 x 8.8 | 24.9 x 19.9 cm: from PhotoSeed Archive

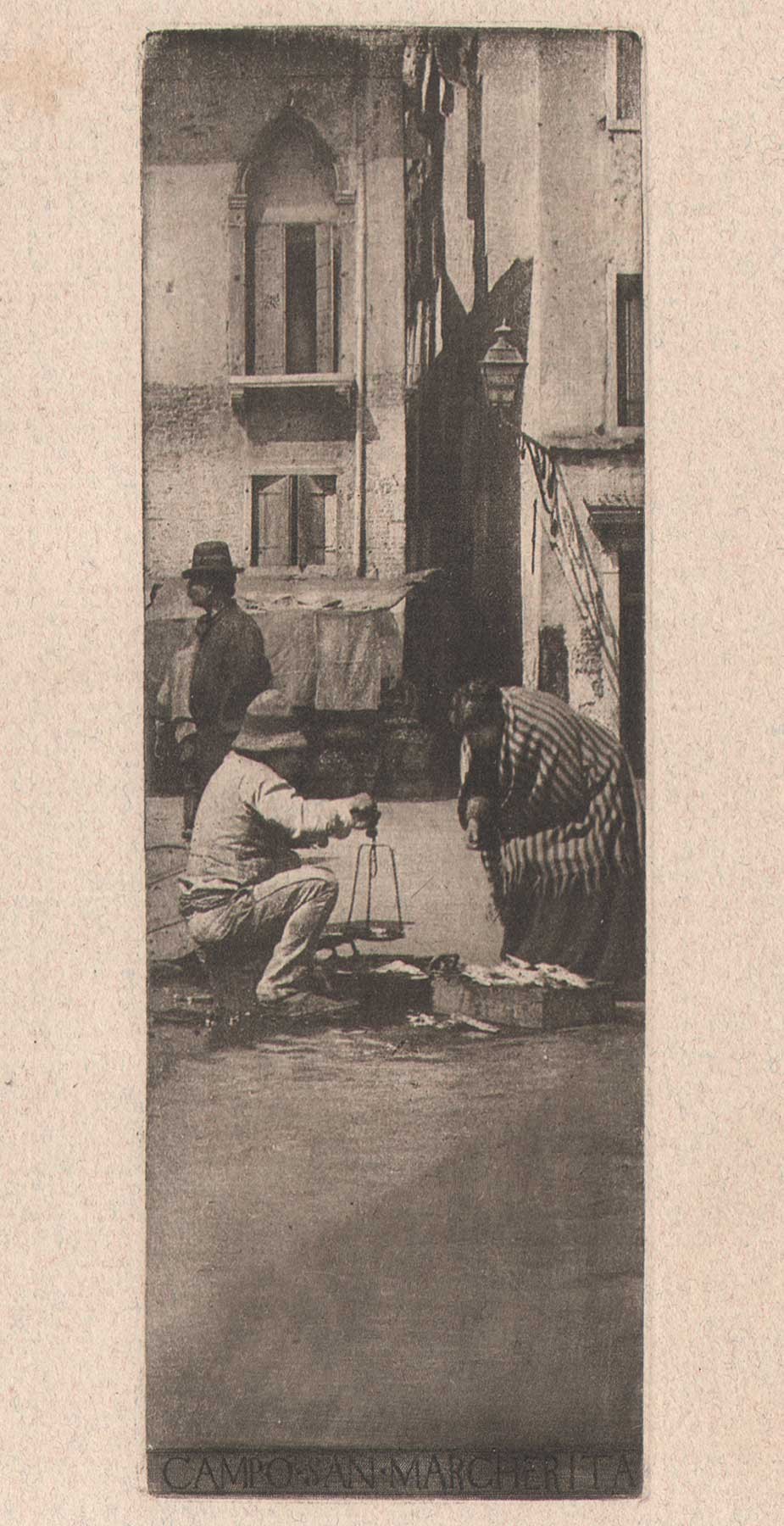

Thank the Calotype

Because the patent restricting Englishman William Henry Fox-Talbot’s 1841 invention of the Calotype process did not apply in Scotland, Hill & Adamson were able to exploit it to full potential. I’ve uploaded an example above, which in viewable form is technically known as a salted paper print from a calotype negative, for comparison. A survivor showing a bit of Gothic architectural detail, it was most likely done between 1845-1855 and found tucked between the pages of this archive’s copy of the aforementioned monthly Art-Union from 1846: the first magazine in history to publish (6000 copies) an example of a Talbotype “Sun Pictures” process calotype.

For a relatively clear understanding of what this early, yet cumbersome two-step process was, former George Eastman House Senior Curator of Photography William R. Stapp wrote in the pages of Image magazine from 1993 on the occasion of a seminal show of original Hill & Adamson calotypes held by the institution:

Calotypes are made on paper. The process requires the photographer to sensitize a sheet of good quality writing paper by brushing it with successive solutions of silver nitrate, potassium iodide, gallic acid, and silver nitrate. After being dried in the dark, the sensitized paper is loaded in the camera; after an exposure of several minutes, the negative is developed by brushing the paper with a solution of gallic acid and silver nitrate, fixed in a bath of sodium thiosulfate (“hypo”) to remove unexposed silver salts, and washed. When dried, this typically dense and contrasty negative is used to make a positive print on so called “salted paper,” which the photographer also has to prepare. This time a sheet of the same good quality writing paper is soaked first in a solution of sodium chloride (ordinary table salt, hence the term “salted paper”), then in a solution of silver nitrate, to produce the halide silver chloride. After it has been dried in the dark, the now light-sensitive salted paper is exposed to the negative in strong sunlight until the image is printed-out on it in deep orange hues. The resulting positive print is fixed in hypo, toned with gold chloride to a rich reddish-brown color, and washed to remove the residual chemistry. In all modern photographic materials, a transparent gelatin emulsion coated on the film or paper support contains the silver particles that form the image. Neither the calotype negative nor the calotype positive has an emulsion of any kind. The image resides literally within the fibers of the paper because the paper itself has been permeated with the photosensitive chemicals. A calotype print consequently incorporates the “tooth” (texture) of both the negative paper and the positive paper in its image. The print has a texture that is both visual and physical, which softens the image and mutes the rendition of detail. (2.)

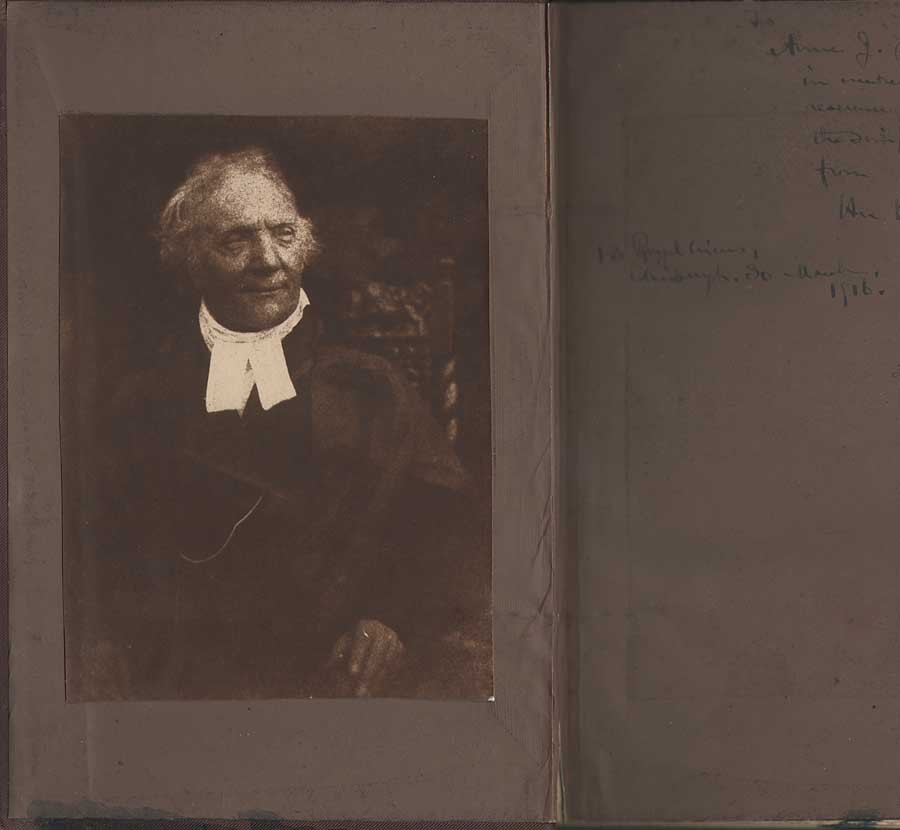

Pasted carbon print: ca. 1916: The Rev. Dr. Thomas Chalmers: (1780-1847) minister, social reformer, leader & first Moderator of the Free Church of Scotland Assembly, Principal of New College, Edinburgh.:15.2 x 11.1 cm: Jesse Bertram: after original ca. 1843 calotype by Hill & Adamson.: shown on opened, inside board cover to volume: “A Selection from the Correspondence of the late Thomas Chalmers, D.D. LL.D.” : Edinburgh: Thomas Constable and Co. : 1853: from PhotoSeed Archive

Activism, and a bit of Fate

As fate would have it, one of those involved with the Scottish Free Church movement was Fox-Talbot correspondent Sir David Brewster. A friend of “Disruption” general assembly moderator, the Rev. Dr. Thomas Chalmers, (1780-1847) who was a minister, social reformer and evangelical orator of high renown chiefly responsible for the secession from the established Church, Brewster early on had learned the Calotype process from his friend Talbot. Teaming with Saint Andrews University chemistry professor John Adamson, they in turn taught it to Adamson’s younger brother Robert Adamson in 1842 after he had moved to Edinburgh.

And the rest they say is history. With Brewster also present at the assembly signing with Hill, he in turn suggested the new process to the painter as a way to solve the dilemma of accurately portraying the hundreds of clergy and others present at the “Disruption” for posterity.

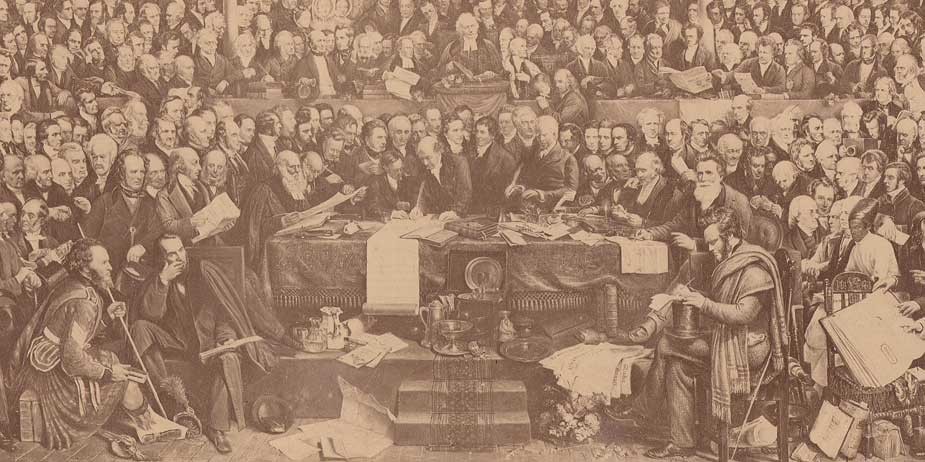

Detail: 1868: far right: Rev. Dr. Thomas Chalmers: Free Church of Scotland moderator along with major figures left to right: Scottish photography pioneer Sir David Brewster, (wearing spectacles looking down at book) Rev. Robert Lorimer, Rev. John Forbes, Dr. David Welsh: undivided Church of Scotland moderator holding a copy of May 18, 1843 church protest that was never answered, Dr. John Fleming, Chalmers. : Thomas Annan: vintage carbon copy photograph after D.O. Hill painting: “The Disruption of the Church of Scotland”completed 1866: original: (13.5 x 31.4 | 34.4 x 41.4 cm ) : from PhotoSeed Archive

Twenty-three years later, most likely with the help of Hill’s second wife Amelia Paton, (1820-1904) a sculptress, the Disruption painting, measuring in finished at over 11 feet by 5 feet, was ready for public display. And this is where it gets interesting for the career of Thomas Annan (1829–1887) and much later, his son James Craig Annan. (1864-1946) The decision to copy the painting for a mass audience was never in doubt for Hill, a man well-connected with the Scottish publishing trade who was born into it; his father being a bookseller and publisher. Hill had even learned the art of lithography from an early age, using it in the reproduction of his own work as a landscape painter for 20 years.

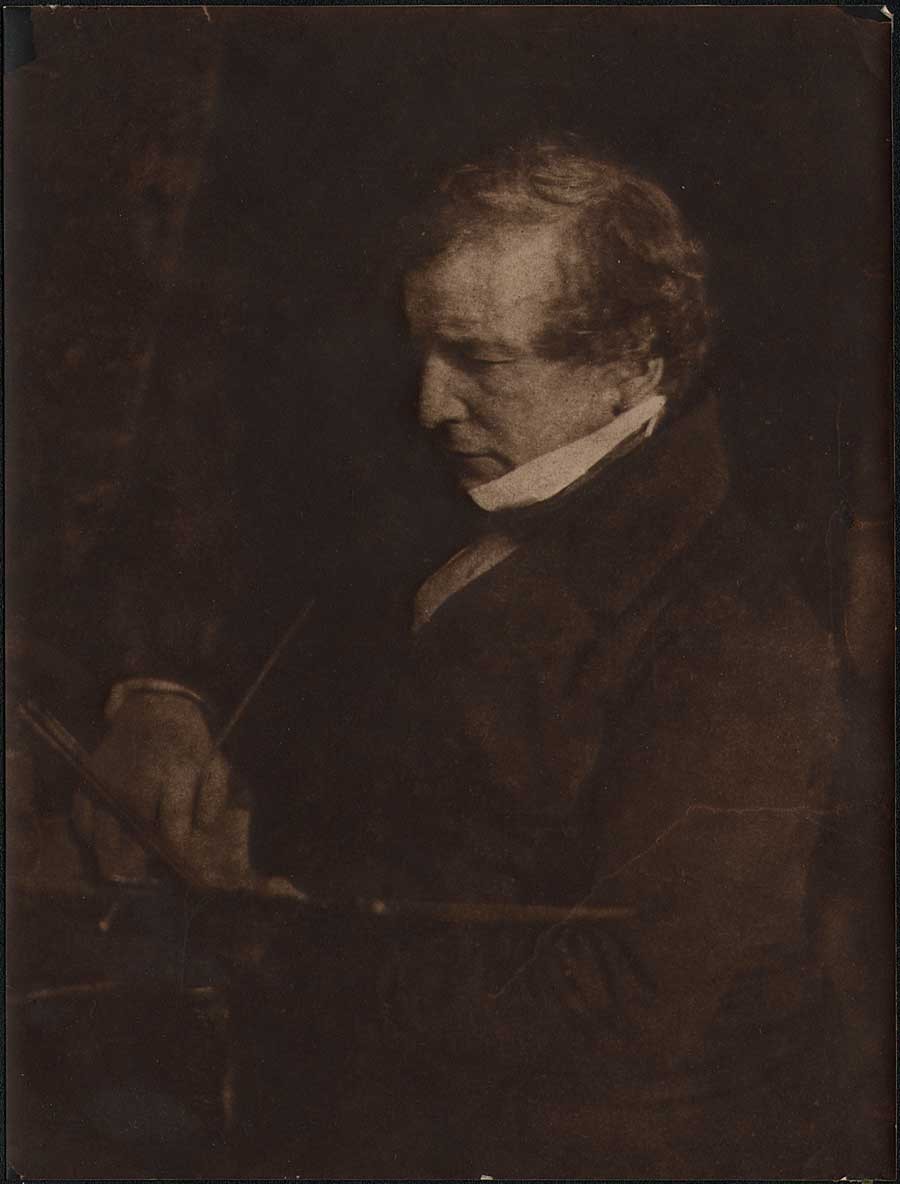

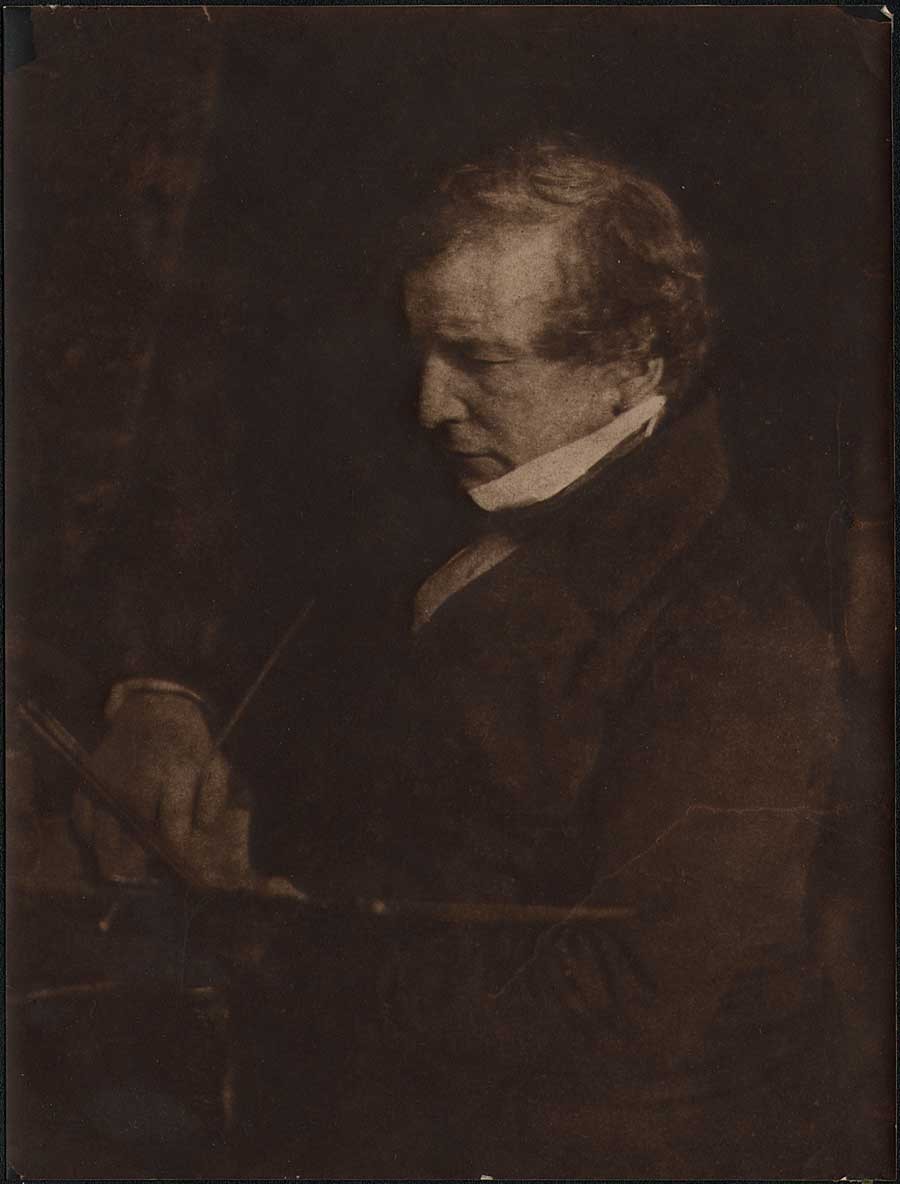

Carbon print: ca. 1879 – 1881 : William Etty, R.A. (English painter: 1787-1849) : Thomas Annan or James Craig Annan: after original 1844 calotype paper negative by Hill & Adamson: 18.5 x 14.0 cm: former collection: Exeter Camera Club: from PhotoSeed Archive

In 1865, shortly before his masterwork was finished, Hill made the acquaintance of Annan by reputation through his brother Alexander’s art gallery in Edinburgh. Annan’s copy paintings had been displayed there, for he had already made a name for himself in this line of work as early as 1862, producing fine copies of artwork for the Glasgow Art Union. These Art Unions “were lotteries connected with the major art exhibitions; the successful subscribers won paintings, and every subscriber received an engraving.” (3)

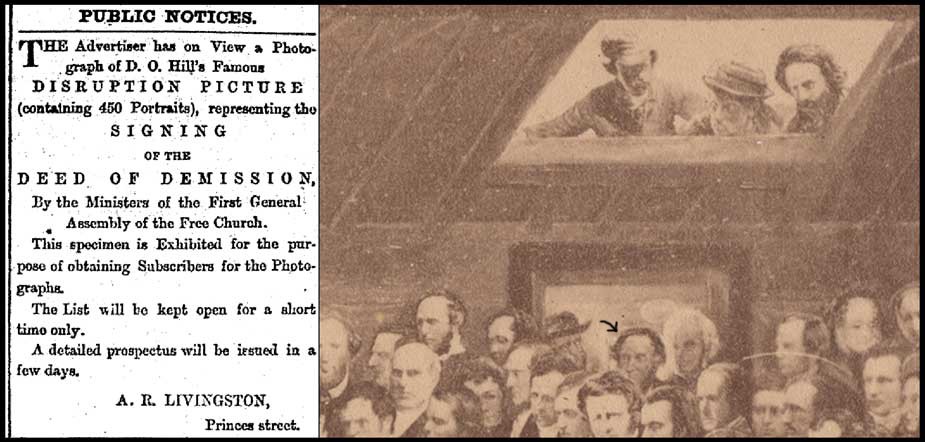

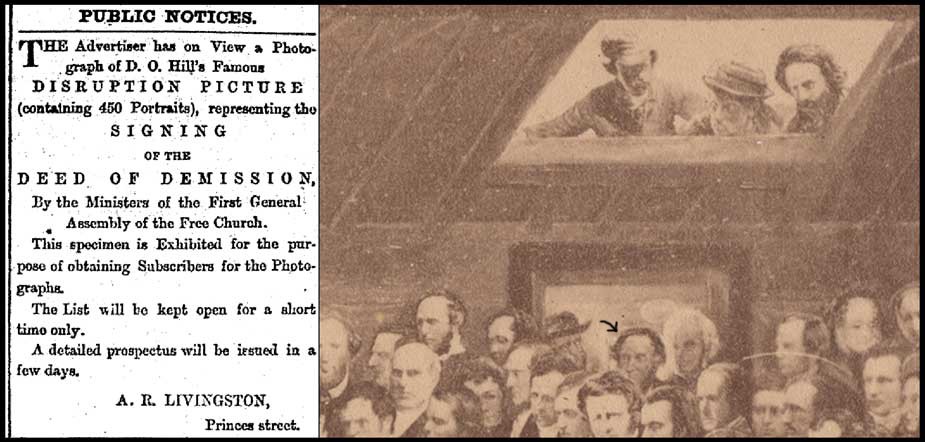

A commission resulted between Hill and Annan to copy Hill’s Disruption masterwork, a canvas that unfortunately- as opposed to the hundreds of Hill & Adamson calotypes used for reference works in its’ creation and now considered masterpieces of the photographic art-did not equate it to a masterpiece itself. Annan employed for this task an improved permanent carbon photographic process, using Joseph Wilson Swan’s 1864 patent carbon tissue to reproduce copies of the “Disruption” after purchasing the Scottish rights from him in 1866. (4.)

Left: 1868: advertisement: New Zealand bookseller A.R. Livingston’s solicitation for Thomas Annan carbon photo of “Disruption Picture” completed 1866 by D.O. Hill: published in Otago Daily Times. Right: 1868: Detail: black arrow pointing to Thomas Annan standing in doorway painted as part of “Disruption” painting (another account states Annan is at left of this figure wearing hat) : Thomas Annan: vintage carbon copy photograph after D.O. Hill painting: “The Disruption of the Church of Scotland”completed 1866: original: (13.5 x 31.4 | 34.4 x 41.4 cm ) : from PhotoSeed Archive

In addition to several detail photos of the painting included with this post, a mounted carbon copy photograph by Annan published in 1868 for the 25th anniversary of the signing of the Act of Separation and Deed of Demission can be seen in our archive here. For those adventurous enough to decipher names and titles of some of those making up the sea of faces in the painting, partly seen below, a fascinating, yet tricky key to some of the major figures can be found here. This was published as part of the 1943 centenary volume The Disruption Picture: A Memorial of the First General Assembly of the Free Church of Scotland by Donald MacKinnon. (5.)

Detail: 1868: At center of table, the Rev. Dr. Patrick MacFarlan (1781-1849) of Greenock is first to sign the “Deed of Demission”, “resigning the highest living in the Church of Scotland at the time”, said to be £ 1000.00 annually, which commemorated the establishment of the Free Church of Scotland: Thomas Annan: vintage carbon copy photograph after D.O. Hill painting: “The Disruption of the Church of Scotland”completed 1866: original: (13.5 x 31.4 cm | 34.4 x 41.4 cm ) : from PhotoSeed Archive

Thomas Annan, Documentarian

With Hill’s work complete, Thomas Annan’s professional career was starting to hit full stride, especially after his success with the Disruption commission. In 1868, the same year a version of this carbon photo was published, (6.) Annan undertook a new commission from the City of Glasgow Improvements Trust that when first published as a series of around 35 albumen prints in 1872, became known as The Old Closes & Streets of Glasgow. As previously outlined in my essay written in 2006 for the Luminous Lint website, Annan’s photographs taken between 1868-1871 are among the earliest done specifically for a record of slum housing conditions prior to urban renewal and as such are an important milestone in the history of documentary photography. (7)

1868: vintage hand-pulled photogravure: “Close No. 193 High Street”: Thomas Annan: from: “The Old Closes & Streets of Glasgow” – photographs taken for the City of Glasgow Improvements Trust : 22.2 x 18.1 | 38.0 x 28.5 cm: 1900: gravure from original collodion glass plate by James Craig Annan: Glasgow: plate #9 from James MacLehose & Sons limited edition of 100: from PhotoSeed Archive

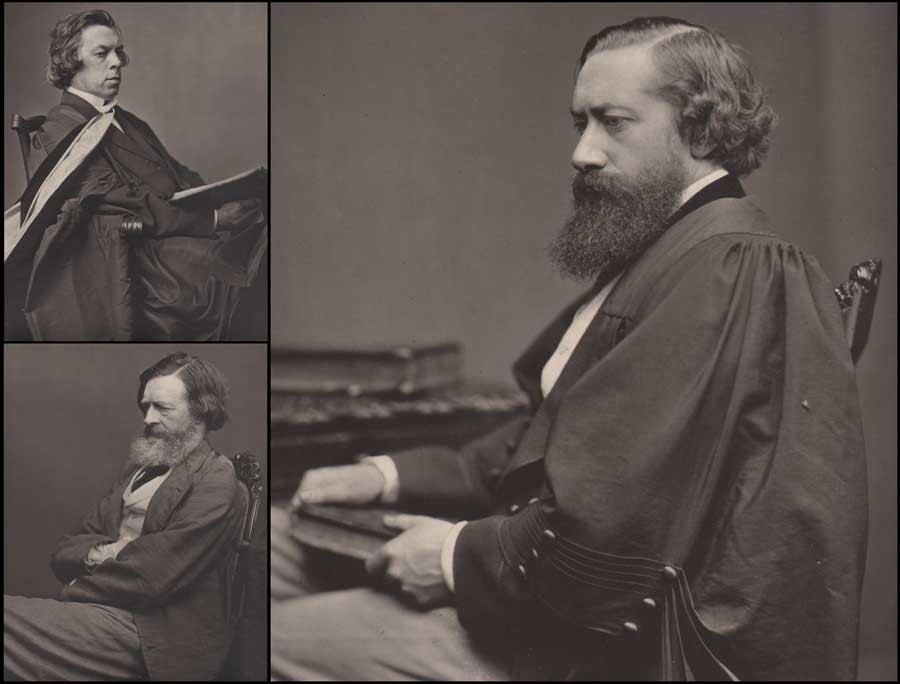

Perhaps knowing her husband’s photographic legacy might be carried on, Amelia Paton bequeathed to Annan “a large collection of calotypes and the portrait lens used by Hill and Adamson” after Hill’s death in 1870. (8.) Speculation he used this very lens for portraits taken soon after for his illustrated volume the Memorials of the Old College of Glasgow, (1871) with examples seen in this post, are an intriguing insight raised by Sara Stevenson in her biography of Annan. (9.) Proportionally, individual portraits taken by Hill & Adamson in the 1840’s compared with those by Annan of the professors from the Glasgow volume and are very similar. However, Annan had the advantage of using the collodion process as opposed to calotype, with the increase of sensitivity of these plates lending a sharpness to his work not possible as movement was often the inevitable result of the slower 2-3 minute exposures required for the older process.

A comparison showing the softness, beauty and masterful composition of a later generation carbon print portrait of English painter William Etty (1787-1849) done ca. 1843 by Hill and Adamson can be seen with this post along with portraits by Annan taken around 1870. These include the striking portrait of professor and theologian John Caird (1820-1898) that reveal compositional similarities between the photographers nearly 30 years apart. With the archival benefit of Annan printing his efforts in permanent carbon, it’s also amusing to see exposure times, although shorter than calotype, did not prevent him in at least one case from seizing the moment in order to permanently memorialize his subject and another unwitting one: a rather large housefly clinging to academic robes worn by University of Glasgow English Language and Literature Professor John Nichol.

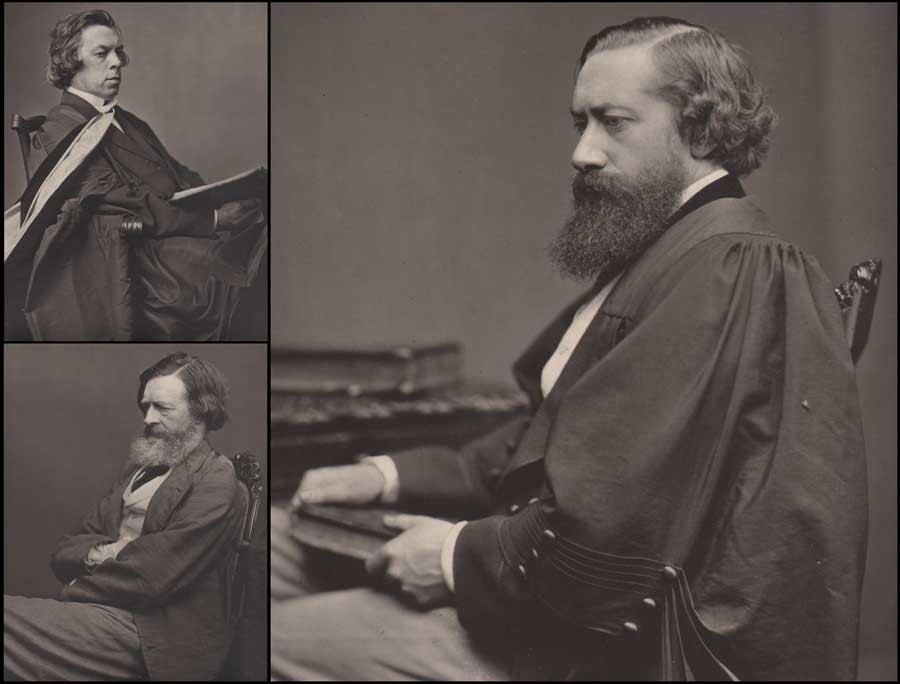

1871: Thomas Annan: mounted carbon portraits from”Memorials of the Old College of Glasgow”(each cropped) : all portraits 21.5 x 16.4 | 36.5 26.0 : upper left: Professor of Divinity John Caird (1820-1898) : lower left: Professor of Greek Edmund Law Lushington (1811-1893) : right: Regius Professor of English Language and Literature John Nichol (1833-1894) (note housefly on academic robe at right below chair back) : from PhotoSeed Archive

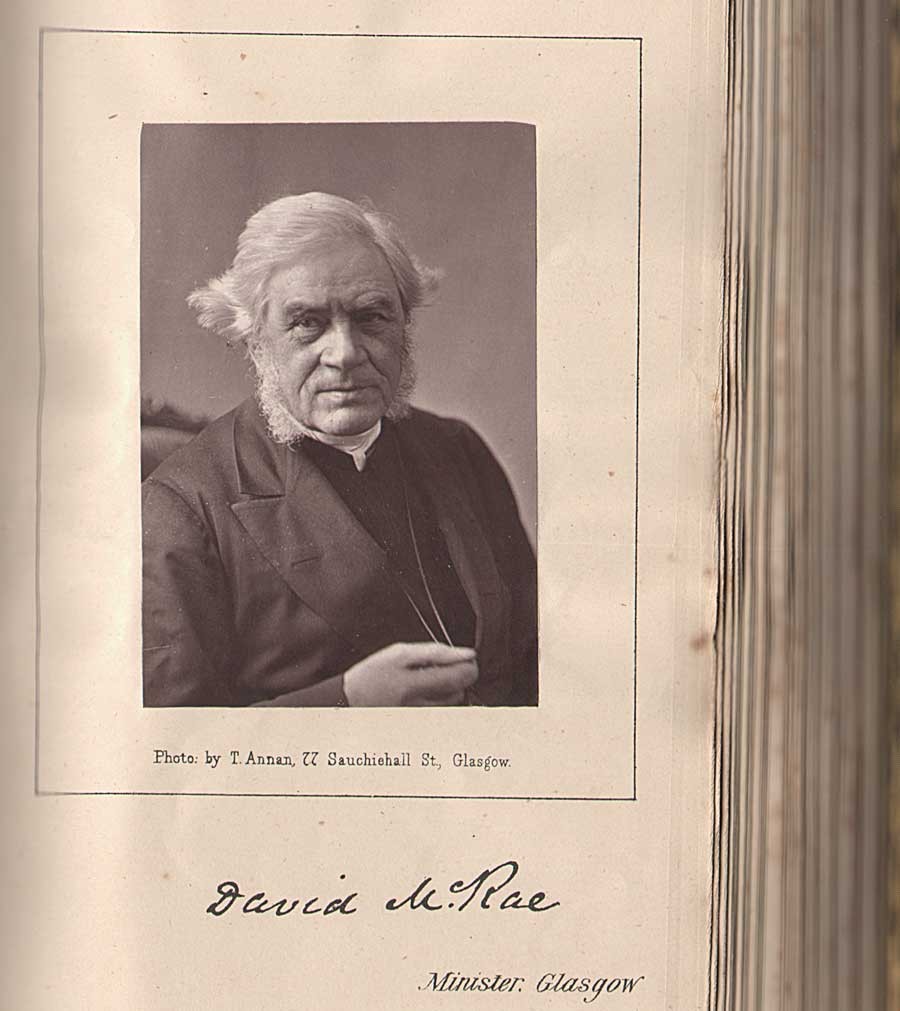

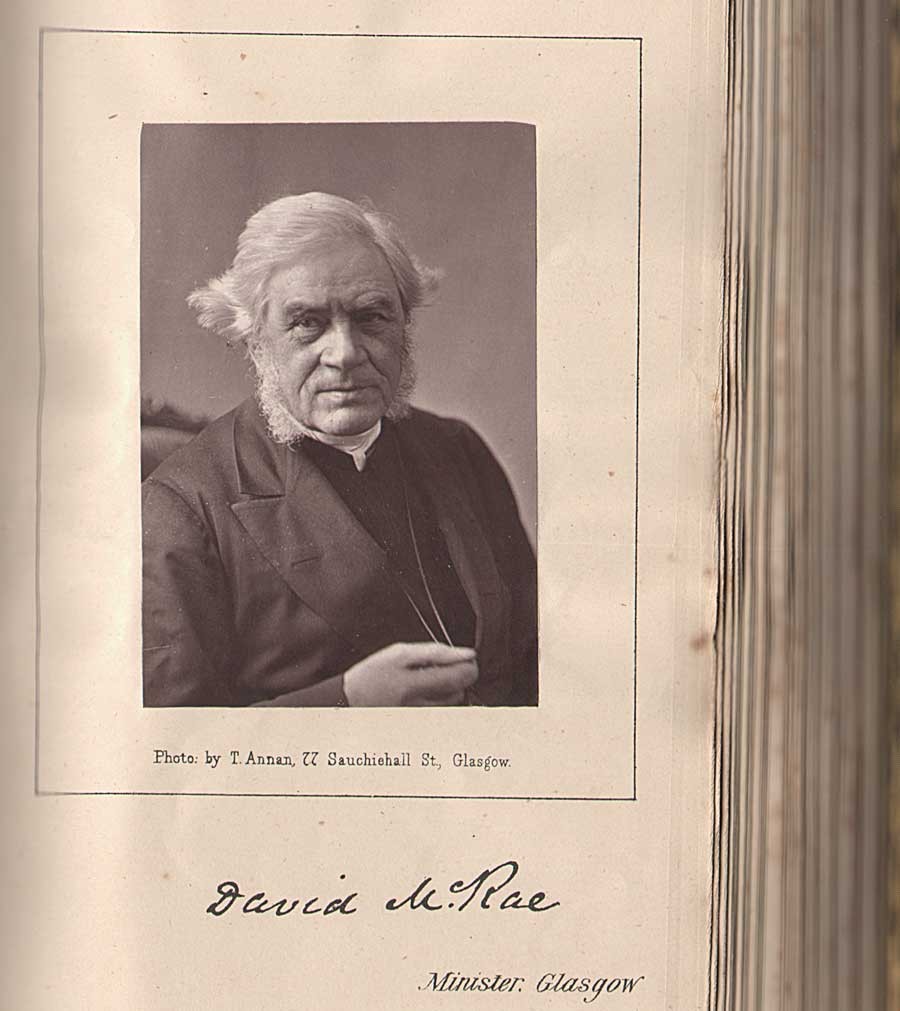

Besides University professors, Annan did many fine portraits of Free Church of Scotland ministers in addition to ministers, elders and missionaries affiliated with the United Presbyterian Church. A unique album of these portraits, reproduced in Woodburytype, is held by this archive, with several appearing in the 1875 Annan published volume Historical Notices of the United Presbyterian Congregations in Glasgow. As a businessman running a commercial studio, Annan marketed many of these images, often as variants, in the carte de visite format. The following is a listing of Annan’s Scotland studios with dates supplied by Peter Stubbs of the EdinPhoto web site:

202 Hope Street, Glasgow: 1862-72

77 Sauchiehall St. Glasgow: 1873-74

153 Sauchiehall St. Glasgow: 1875-91

75 Princes St. Edinburgh: 1876-82

1873-74: Rev. David McRae of Glasgow: (a leading temperance movement leader from the 1850-70’s) mounted Woodburytype portrait with facsimile autograph: Thomas Annan: 8.3 x 5.6 | 19.4 x 10.5 cm : from unique folio album of nearly 60 Woodburytype photographs taken ca. 1862-1882 by Thomas Annan and most likely John Annan of ministers, elders and missionaries affiliated with the United Presbyterian Church: from PhotoSeed Archive

Coming full-circle: Learning Photogravure

In 1883, after purchasing the British rights to a new process of Photogravure invented by Czech artist Karl Klíc, (1841-1926) Thomas Annan and son James Craig Annan traveled to Vienna in order to personally learn its intricacies. As defined by our good friends over at Photogravure.com, Klíc’s 1879 refined process of “reproducing a photograph by printing on paper from an inked and etched copper plate” was a vast improvement over that of William Henry Fox Talbot’s 1858 patented Photoglyphic Engraving process. Thomas Annan was so smitten he wrote Klíc the following appreciation:

“I beg to express my entire satisfaction with your gravure process… The process itself is very valuable to a fine art publisher because of the beauty of the work and the crafted manner in which the plates are executed. With many thanks to me and my son I remain, Dear Sir, yours very truly” – Thomas Annan March 11, 1883 (10.)

Fittingly renamed the Talbot-Klíc Dust Grain Photogravure by Klíc, the process was soon fully embraced by Annan’s publishing concerns, T. & R. Annan and Sons of Glasgow, Hamilton and Edinburgh, who utilized photogravure for high-quality, fade-resistant and archival plates, mostly copies of original works of art, an established specialty. Soon, the new process, which involved the individual hand-pulling of plates from a copper-plate press, was further exploited and refined by the budding photographer James Craig Annan in the early 1890’s, whose original photographic negatives “from nature” during his travels to the Continent, particularly North Holland and Italy, were directly reproduced in gravure after an ongoing period of great experimentation and refinement.

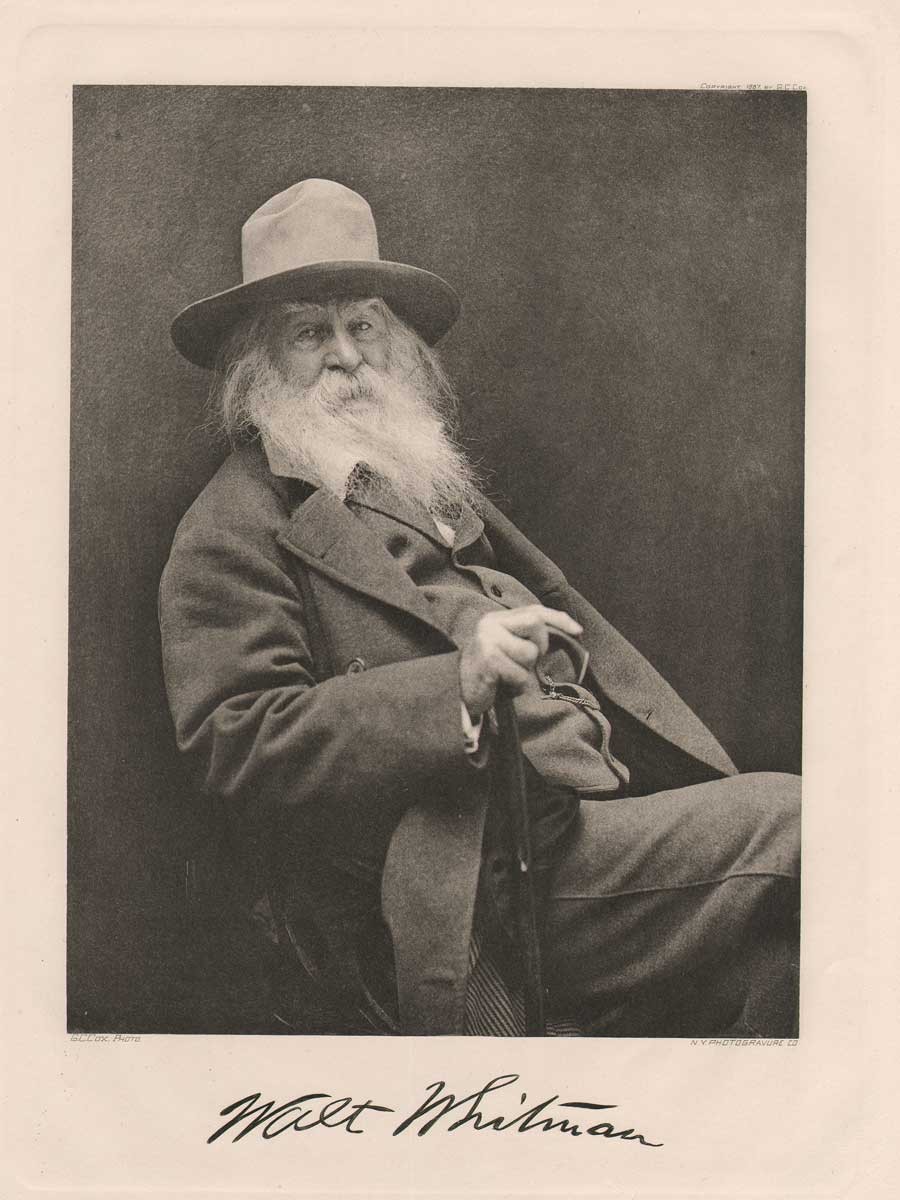

Like his father Thomas, who reproduced and exhibited some of the Hill & Adamson calotypes in carbon during the 1870’s and early 80’s using his own refinements of Swan’s process, (11.) James Craig Annan fully embraced Talbot-Klíc gravure printing to reinterpret their landmark achievements in early pictorial portraiture as well as other studies including the fisherfolk of Newhaven near Edinburgh. In this regard, beginning as early as 1890, Annan produced a series of hand-pulled gravures re-photographed from the original Hill & Adamson paper calotype “negatives in the possession of Andrew Elliott.” (12.) Later in 1905, working as part of the T & R Annan firm of Glasgow, he produced a further series of 20 plates printed on Japan tissue. (13.) These copper plates were then re-used for a series of gravures published in Alfred Stieglitz’s Camera Work XI, (1905) XXVIII, (1909) and XXXVII, (1912) thereby introducing new generations to the masterful legacy left by Hill & Adamson.

1890-1912: “Girl in Straw Hat” (Miss Mary McCandlish) : vintage hand-pulled photogravure trimmed and mounted within cream paper folder: possibly a 1912 Camera Work proof: 21.5 x 15.9 |25.5 x 19.0 cm: James Craig Annan after original paper calotype ca. 1843-47 by Hill & Adamson: reproduced in CW XXXVII: originally in Margaret Harker Collection: from PhotoSeed Archive

I’ll end this lengthy post with an excerpt from an appreciation of D.O. Hill by James Craig Annan, who was fortunate to have met and been inspired by the artist when he was only six years old- the result of his father being an intimate friend of Hill. This was included as part of a larger essay he wrote on the Scottish pioneer for Camera Work XI, and he makes the strong case their achievement was a direct result of their portrait collaborations for the Disruption painting:

“Thus the partnership began which was to produce the noble and extensive series of portraits which for powerful characterization and artistic quality of uniformly high excellence have certainly never been surpassed and possibly not even rivaled by any other photographer. This may seem an extravagant appreciation of Hill’s work, but it has been arrived at after mature deliberation.” (14.)

-David Spencer

Notes:

1. British Artists: Their Style and Character: With Engraved Illustrations. : David Octavius Hill, R.S.A.: in: The Art-Journal: London: October 1, 1869: p. 317

2. William F. Stapp.: Hill and Adamson: Artists of the Calotype: from: Image: George Eastman House: Spring/Summer: Vol. 36: No. 1-2: 1993: p. 55

3. Sara Stevenson: Scottish Masters 12: Thomas Annan: National Galleries of Scotland: 1990: p. 5

4. After discussions with Hill, the copy photograph of the “Disruption“canvas was taken by Thomas Annan after he had ordered “a large Photographic Camera of the latest and most perfect construction” from Dallmeyer: in: 1866 Disruption prospectus by Hill: published in: Scottish Masters 12: p. 7

5. Alan Newble has thoughtfully, and no doubt, painstakingly, compiled the key as part of his website, with further insights on the historical importance of the Rev. Dr. Thomas Chalmers.

6. In correspondence between Annan and Hill in late December, 1865, Hill stated he wanted the Disruption painting reproduced in thousands of photographs in 3 separate sizes. “He (Hill) was hoping for prints half the size of the painting, and suggested that Annan make them in three parts, joining them together around the figures rather than in an arbitrary straight line.” : from: Hill & Annan letters: quoted in: Scottish Masters 12: pp. 6-7. Alas, Hill’s desires were trumped by technical limitation, with carbon prints supplied by Annan printed in 1866 in 3 sizes, as stated in the Photographic News of London: “Photographs of the picture will be issued in three sizes, ranging from 24 inches by 9 inches to 48 inches by 21 1/4 inches, at prices ranging from a guinea and a half to twelve guineas.”

7. The carbon print edition of Old Closes first appeared in 1877, with two later photogravure editions featuring 50 plates each printed by James Craig Annan published in 1900. Fine examples of the albumen prints from Old Closes can be found along with superb background on their making at the University of Glasgow Library special collections department online resource found here.

8. cited in Scottish Masters 12: p. 8

9. Ibid: p. 13

10. from: Photogravure.com online resource accessed August, 2014. While in Vienna under Klíc’s watchful eye, the Annans had produced a photogravure of Noel Paton’s painting of The Fairy Raid.

11. Scottish Masters 12: p. 8

12. David Octavius Hill & Robert Adamson: in: The Collection of Alfred Stieglitz: Weston Naef: New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art: p. 378. Elliott, (1830-1922) was a nephew of D.O. Hill

13. Ibid, p. 378

14. excerpt: David Octavius Hill, R.S.A. 1802-1870.: J. Craig Annan: in: Camera Work XI: New York: edited and published by Alfred Stieglitz:1905: p. 18