The 1905 Kodak Competition | Exhibition & Kodak Advertising Contests

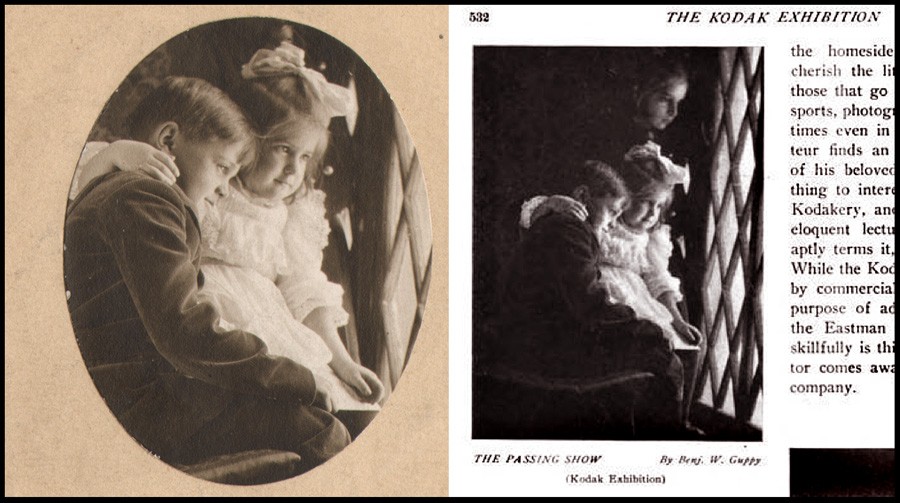

The cryptic title of this post owes a debt to advertising. Seeing an opportunity to redefine their annual photographic contest for 1905 by marketing products to all kinds of photographers, the Eastman Kodak Company decided to embrace the two distinct schools of the period.

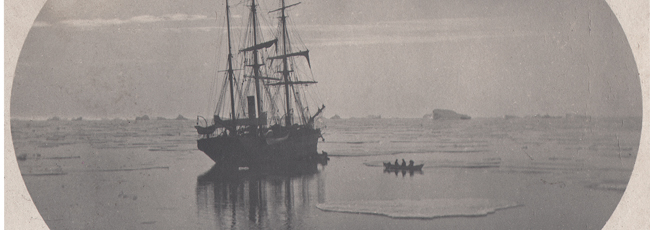

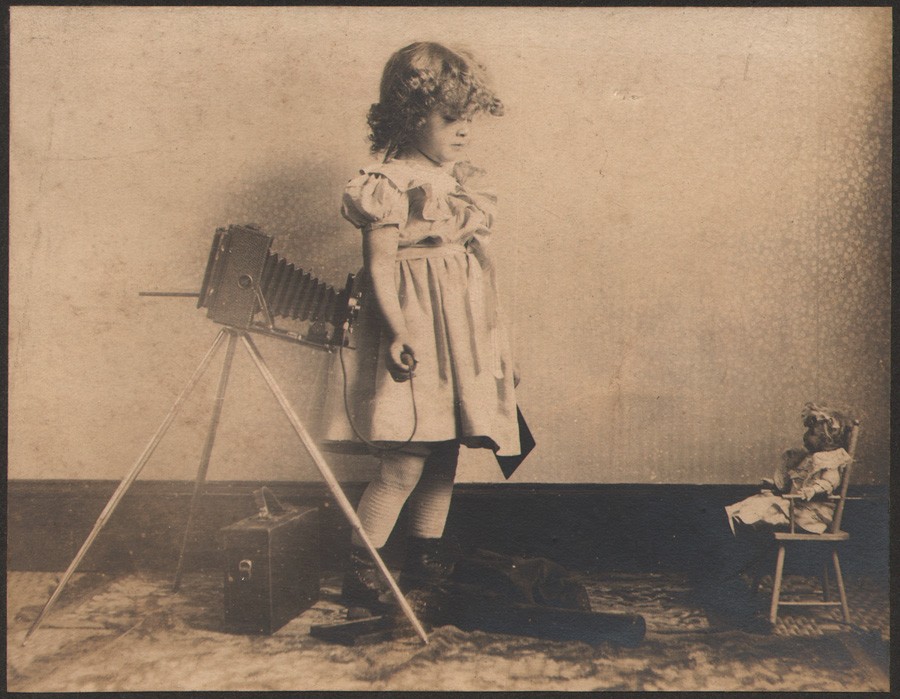

Taken ca. 1903-05 and the subject of an extensive series of photographs by her amateur photographer father from infancy to late teens, Dorothy (b. August, 1899, of Staten Island, N.Y.) prepares to squeeze a bulb shutter while photographing her dolly. This photograph or variant was likely entered in one of the annual “Kodak Competitions” from the period, as it features the company’s products, including a tripod-mounted plate camera. (undetermined model) A camera and tripod case can be seen on floor along with a single plate holder and dark cloth. Dorothy holds the dark slide for the camera in her left hand while making the exposure. Mounted vintage gelatin silver print: 17.9 x 22.0 cm | 11.0 x 14.1 cm: from: PhotoSeed Archive (photographer details withheld pending further research)

The so-called “straight” shooters, whose intent was a picture sharply in focus and the “pictorialists”; those embracing the painterly concept of selective focus in their work.

Letterpress detail from cover: (24.2 x 18.0 cm) “Souvenir Kodak Competition 1905”. This souvenir book is believed to have been published sometime in 1906 or 1907, the culmination of one of the company’s annual contests which included public exhibitions in major American cities at the end of 1906 and through March of 1907. From PhotoSeed Archive

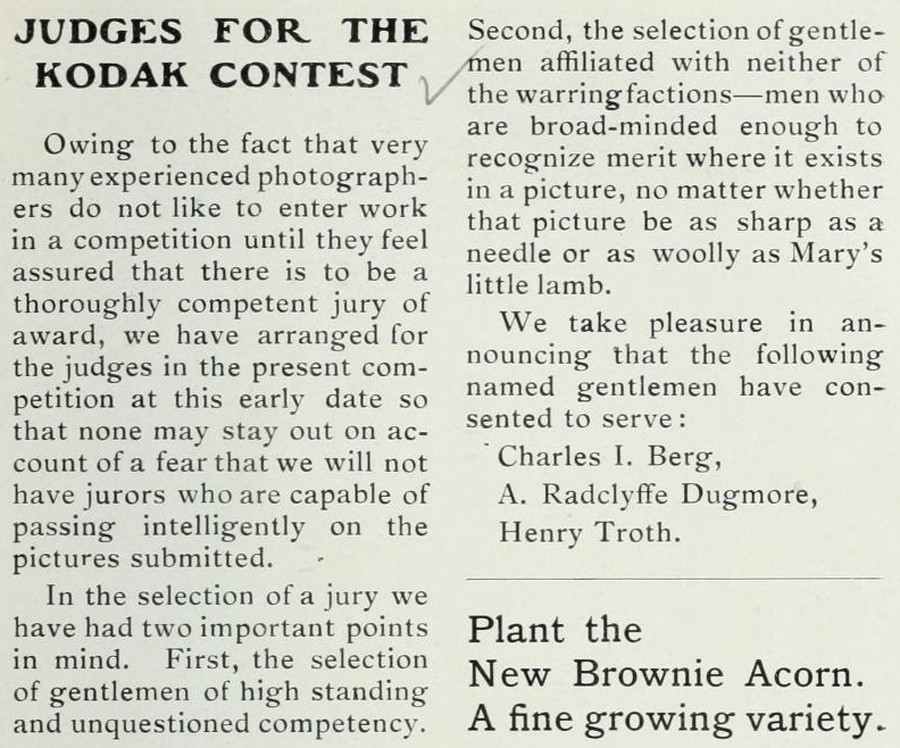

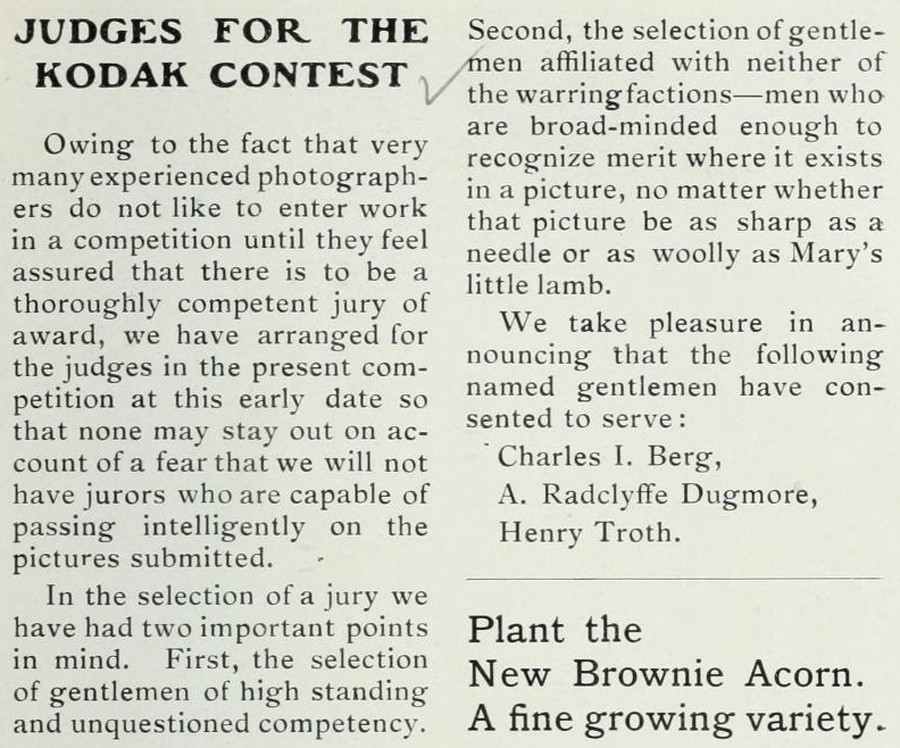

This inclusivity was emphasized after the company announced criteria for their selection of judges for the 1905 contest:

In the selection of a jury we have had two important points in mind. First, the selection of gentleman of high standing and unquestioned competency. Second, the selection of gentlemen affiliated with neither of the warring factions men who are broad-minded enough to recognize merit where it exists in a picture, no matter whether that picture be as sharp as a needle or as woolly as Mary’s little lamb. (1.)

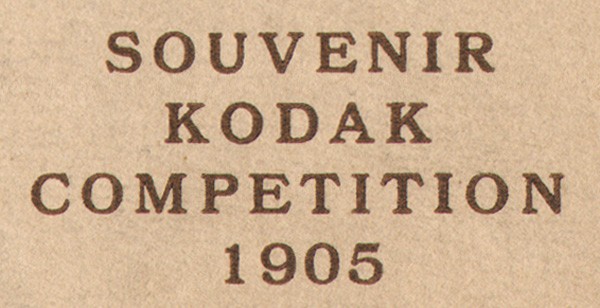

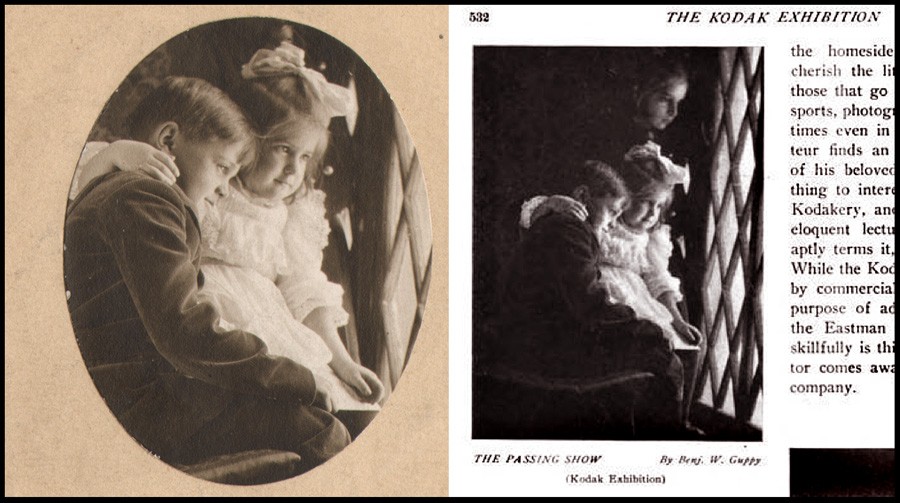

Left: Maine resident and amateur photographer Benjamin Wilder Guppy (1870-1960) won $10.00 and an honorable mention in the “1905 Kodak Competition” for this photograph: “The Passing Show”, used as the cover photograph of the souvenir book: gelatin silver print: 6.6 x 5.2 cm. (PhotoSeed Archive) Right: the uncropped version of “The Passing Show” as it appeared in the Kodak exhibitions from 1906-07.: source: halftone from: “The Photographic Times”: New York: December, 1906: p. 532

Rhetoric aside, these judges certainly had artistic ambitions. They were:

Charles Berg: (1856-1926) studied at the Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris and London, opening an architectural practice in New York City in 1880, and later designing one of the city’s earliest skyscrapers, the Gillender Building. In 1896 he became a founding member of the Camera Club of New York, and his amateur work reflected his classical training-classically draped models often surrounded by architectural elements.

Arthur Radclyffe Dugmore: (1870-1955) at the time of the 1905 contest a pioneering nature photographer, he had the distinction in 1903 of one of his photographs, “A Study in Natural History“, a photogravure of baby birds, appearing in the first issue of Camera Work I. He later became a recognized painter and printmaker.

Henry Troth: (1863-1948) was an active member of the Photographic Society of Philadelphia, a pioneering artistic photography society in the United States. A professional photographer specializing in genre and the natural world, his work appeared in magazines and volume compilations of poetry and verse, often uncredited, such as Poetry of Nature. (1909)

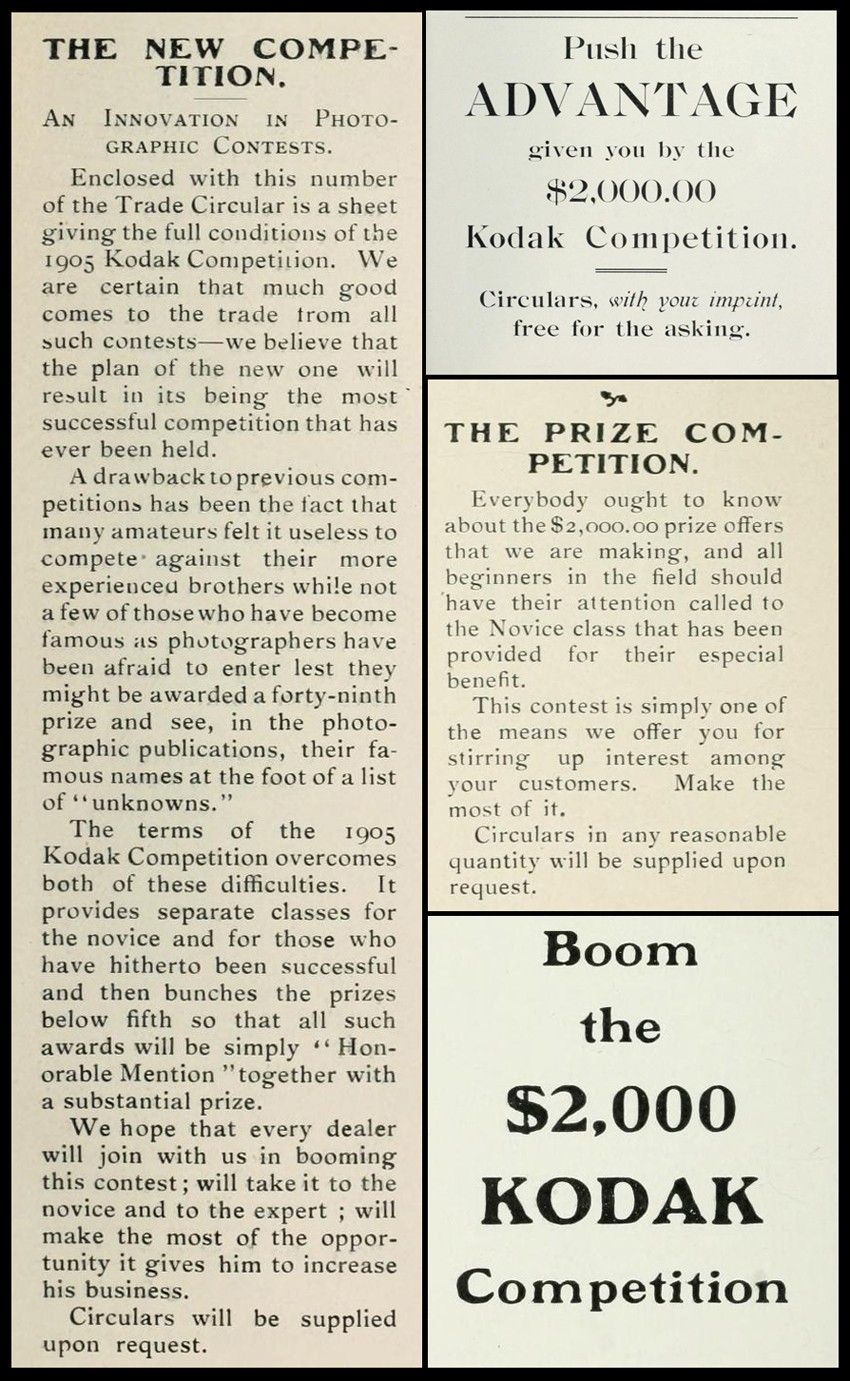

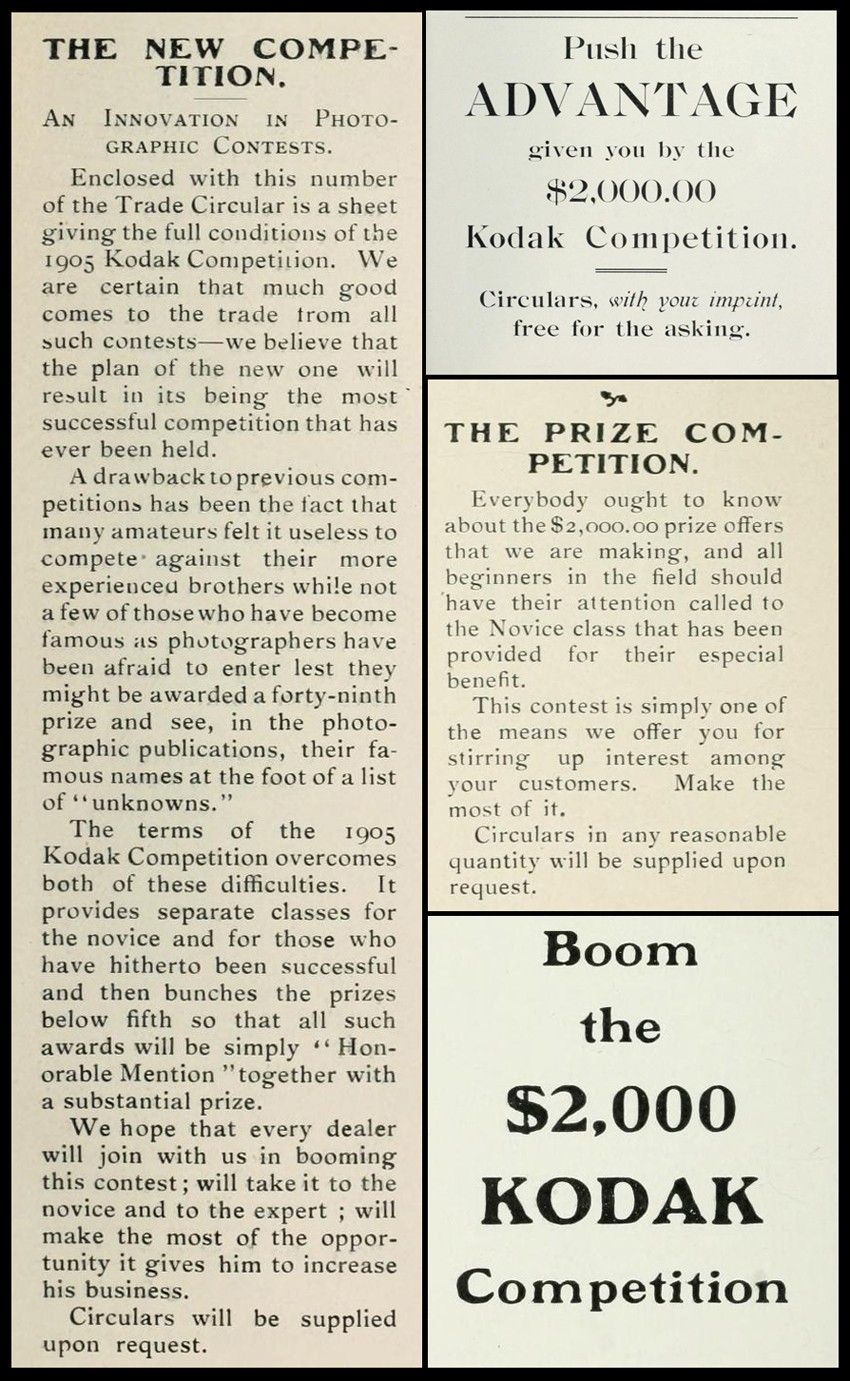

The 1905 Kodak Competition as well as the annual contests that followed were heavily promoted by the Eastman Kodak Company in their dealer trade circulars. This composite of editorial and advertising matter are taken from 1904-05. Left: first notice for the contest appeared in December, 1904. Right column, top: Kodak dealers are told of the Advantage they would receive (in increased sales) by “pushing” the contest on their customers. Middle: In January, dealers are alerted that “all beginners in the field should have their attention called to the Novice class that has been provided for their especial benefit.” “This contest is simply one of the means we offer you for stirring up interest among your customers.” Bottom: The term “Boom”, an arcane word similar to “Shout” from the beginning of the 20th century, was used in an advertisement for the contest in the May, 1905 issue of the circular. Letterpress pages from Canadian Kodak Co., Limited Trade Circular: Toronto: online resource courtesy Ryerson University Library Special Collections

Particulars

In late 1904, Kodak announced they would break down and eliminate what they felt had been barriers for amateurs and professionals alike in regard to photographic contests up to that period:

A drawback to previous competitions has been the fact that many amateurs felt it useless to compete against their more experienced brothers while not a few of those who have become famous as photographers have been afraid to enter lest they might be awarded a forty-ninth prize and see, in the photographic publications, their famous names at the foot of a list of unknowns.

The terms of the 1905 Kodak Competition overcomes both of these difficulties. It provides separate classes for the novice and for those who have hitherto been successful and then bunches the prizes below fifth so that all such awards will be simply “Honorable Mention” together with a substantial prize. (2.)

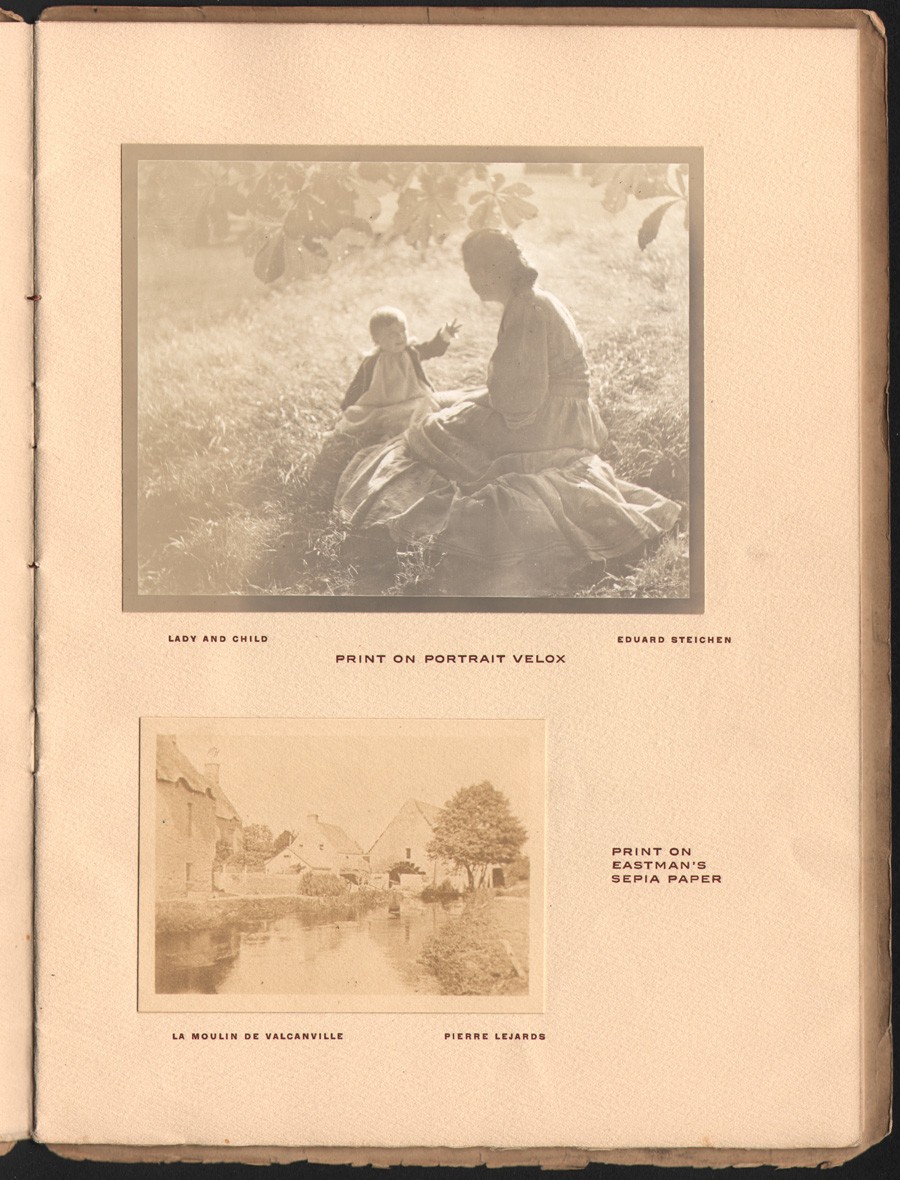

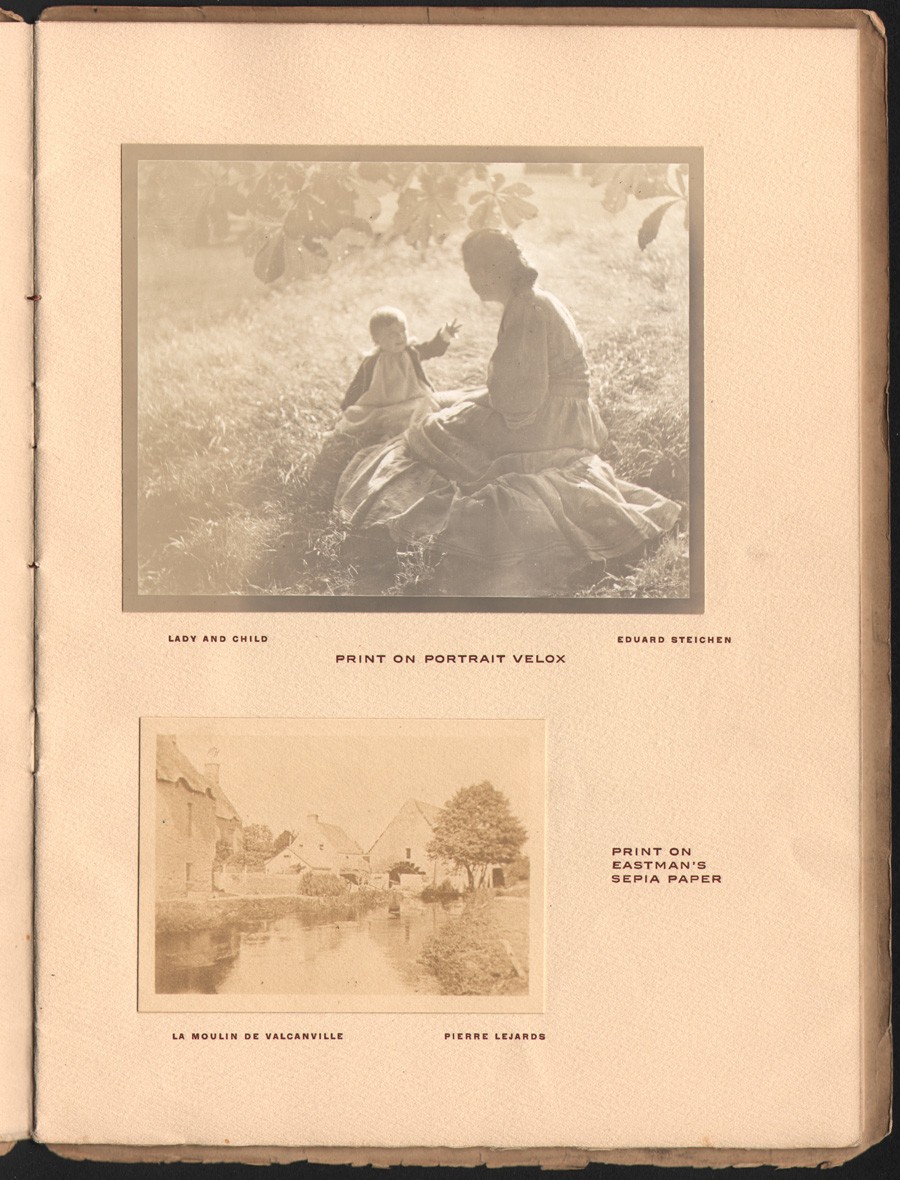

Ten original photographs printed on Kodak gelatin silver papers are featured in the souvenir book for the 1905 Kodak Competition. Top: “Lady and Child”, (9.8 x 12.2 cm | 9.1 x 11.5 cm) likely from a copy negative or print, (as it includes a gray border) is by American master Edward Steichen. Printed on Portrait Velox paper, it is also known as Mother and Child — Sunlight, (published as a photogravure in Camera Work XIV) and won the $150.00 first prize for him in the Class A Open category, featuring negatives 3 ¼ x 4 ¼ or larger in size. Bottom: “La Moulin de Valcanville” (6.2 x 8.5 cm |5.4 x 7.8 cm) by Pierre Lejards of Paris, France is printed on Eastman’s Sepia Paper. It was awarded honorable mention and earned him a No. 0 F.P. Kodak camera in the Class F Novice category. (Brownie Pictures) from: PhotoSeed Archive

A true marketing ploy, the company also made sure there would be plenty of time for those contemplating a submission for the contest. In America, entrants had up to November 1st to enter and in England, a month earlier, although this was changed to a later date to accommodate the mailing of the large amount of submissions, which totaled 28,000 entries worldwide. Particulars for the contest were printed in multiple publications, including the January 1905 issue of Camera & Dark-Room:

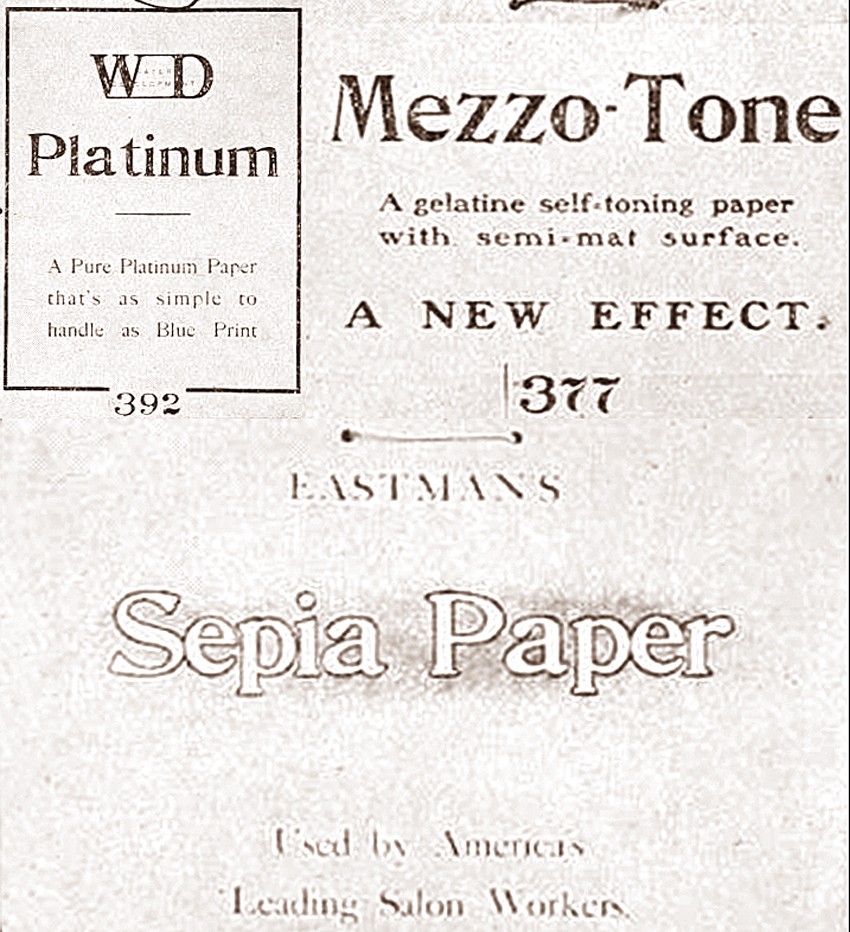

The September, 1904 issue of the Kodak Trade Circular featured brand logos of various Kodak papers, including W-D Platinum, (water development) Mezzo-Tone, and Eastman’s Sepia Paper. Along with Portrait and Velvet Velox, the papers were used to print winning entries for the 1905 Kodak Competition souvenir book. Composite letterpress advertisements: Canadian Kodak Co., Limited Trade Circular: Toronto: online resource courtesy Ryerson University Library Special Collections

The 1905 Kodak Competition.

We have pleasure in announcing that another great picture competition is to take place during the year. The Eastman Kodak Company offer $2,000 in prizes and have arranged for two classes of competitors, “Open” and “Novice.” The “open” class is for all who may care to enter, but the “novice” is open only to amateurs who have never won a prize in a photographic contest. This is a feature which will greatly please many who do good work but who do not care to compete against the regular pot hunters.

“Sharp as a needle or as woolly as Mary’s little lamb” : In announcing the three judges for the 1905 Competition, the April, 1905 issue of the Kodak Trade Circular let it be known the contest would be open to all schools of photography, as well as degrees of experience. from: Canadian Kodak Co., Limited Trade Circular: Toronto: online resource courtesy Ryerson University Library Special Collections

The classes and conditions are as follows:

Class A. Open to all. For Kodak pictures 3 ¼ x 4 ¼ or larger, including the Panoram Kodaks.

Class B. Open to all. For Kodak pictures 3 ½ x 3 ½ or smaller, including No. 1A Folding Pocket Kodak.

Class C. Open to all. For enlargements of any size from Kodak or Brownie negatives on Eastman. Nepera or Photo-Materials Bromide Paper.

Class D. Novice. Open only to amateurs who have never been awarded a prize in a photographic contest. For Kodak pictures 3 ¼ x 4 ¼ or larger, including the Panoram Kodaks.

Class E. Novice. Open only to amateurs who have never been awarded a prize in a photographic contest. For Kodak pictures 3 ½ x 3 ½ or smaller, including No. 1A Folding Pocket Kodak.

Class F. Novice. Open only to amateurs who have never been awarded a prize in a photographic contest. For Brownie pictures only.

All pictures sent in for competition must be from negatives made with a Kodak or Brownie on Kodak N. C. Film, and must be printed on papers manufactured or sold by us.

PRINTS ONLY are to be sent in; not negatives.

Prints must be mounted, but not framed.

The title of the picture, with the name and address of the competitor, class entered for, and the name of the printing paper used for the pictures, must be legibly written on the back of mount.

The films must have been exposed by the competitor, but it is not necessary that competitors finish their own pictures.

No competitor will be awarded more than one prize in a class.

Not more than one prize will be awarded to prints from one negative, except that all Velox Prints will be considered In the awarding of the Special Velox Prizes regardless of the prizes said prints may have received in the other classes.

Contact prints from the same negative cannot be entered in two classes.

This contest closes at Rochester. N. Y., on November 1, 1905; at Toronto. Canada, on October 20, 1905. and at London, Eng., on October 1, 1905.

All entries sent in from the United States and the possessions thereof and from South America should be addressed to EASTMAN KODAK CO..

Kodak Contest Dep’t. Rochester, N. Y. (3.)

Detail: Alfred Stieglitz: “Soap Bubbles”, from 1905 Kodak Competition Souvenir book. (8.8 x 14.4 cm | 8.0 x 13.7 cm) Printed on Velvet Velox and believed to be from the original negative, Stieglitz received an honorable mention and $20.00 in the Kodak contest in Class C Open category for Enlargements. from: PhotoSeed Archive

History of Kodak Competitions

Little scholarship seems to have been spent on the annual photographic competitions which in turn lead to public exhibitions sponsored by the Eastman Kodak Company in the early years of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Besides accomplishing the desired result of brand recognition, they are undoubtedly a rich resource for understanding the changing aesthetic trends for primarily amateur photography during this period.

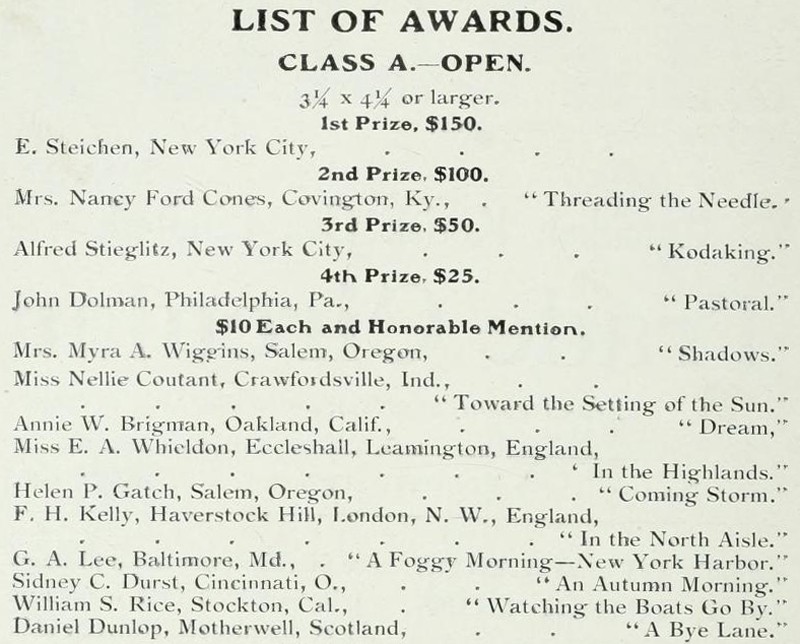

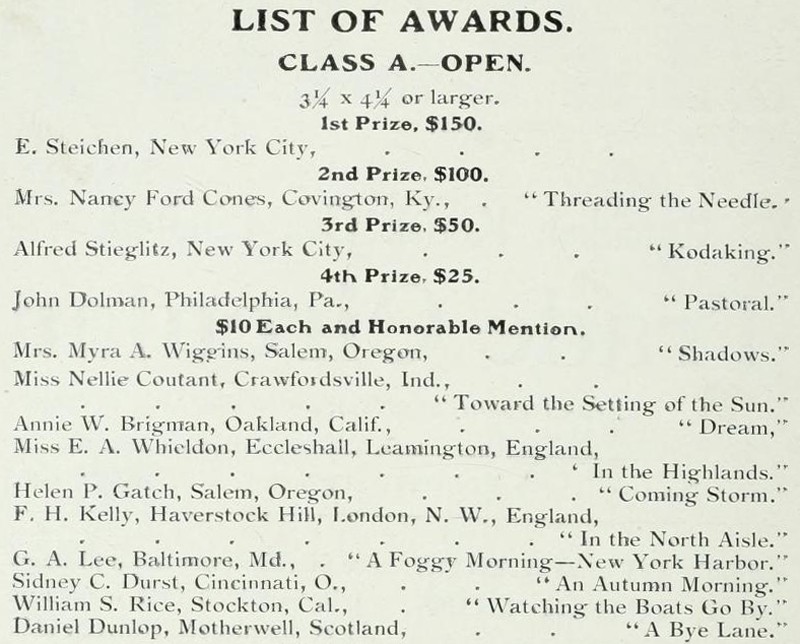

Detail: letterpress: Awards for the 1905 Kodak Competition were announced and listed in March, 1906. Some of the results for the bigger names who competed in Class A, Open category, (negatives 3 ¼ x 4 ¼ or larger in size) are seen here. From: Canadian Kodak Co., Limited Trade Circular: Toronto: March, 1906: online resource courtesy Ryerson University Library Special Collections

Of the resulting exhibition which the 1905 competition spawned, a Photographic Times editor provided an overview but also gave it a veiled endorsement after it closed at Madison Square Garden Concert Hall in New York City in November, 1906:

While the Kodak Exhibition is prompted by commercial interests and is for the purpose of advertising the products of the Eastman Kodak Company, yet so skillfully is this concealed that each visitor comes away feeling indebted to the company.

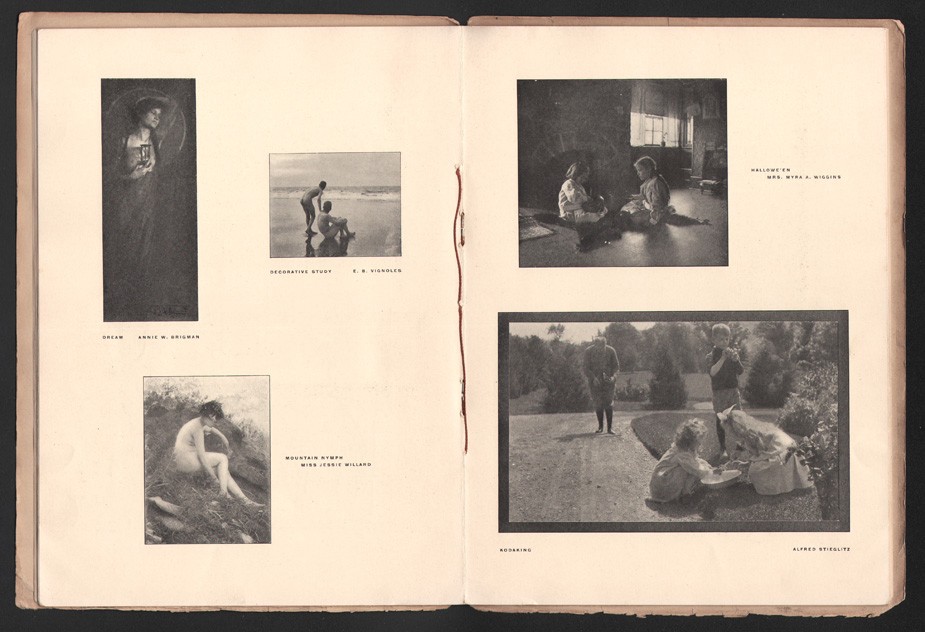

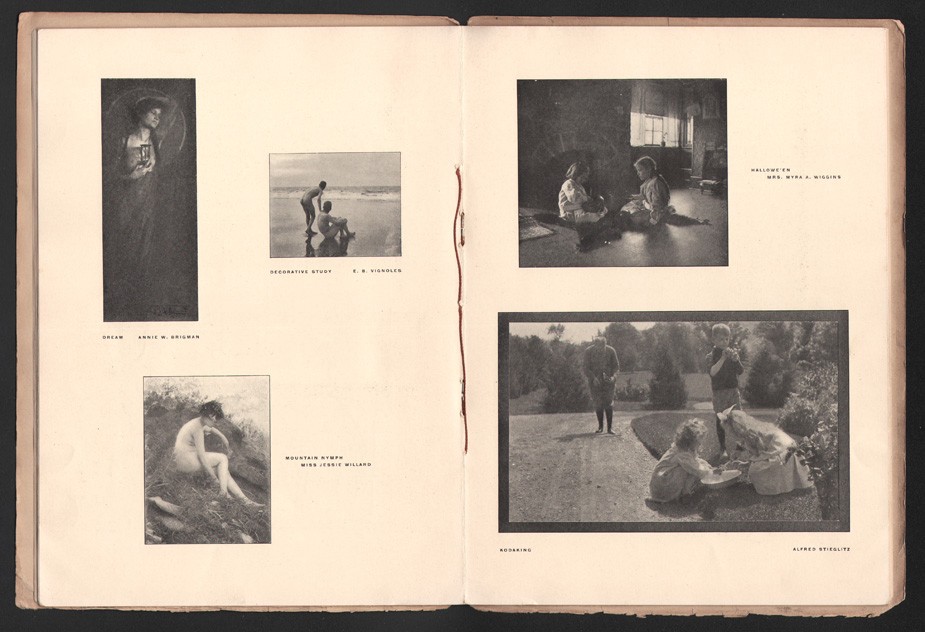

20 winning photographs printed as halftones (printed on coated manilla stock) are featured in the souvenir book for the 1905 Kodak Competition. This representative page spread features clockwise from top left: “Dream” by Annie W. Brigman, “Decorative Study” by E.B. Vignoles, “Hallowe’en” by Mrs. Myra A. Wiggins, “Kodaking” by Alfred Stieglitz, “Mountain Nymph” by Miss Jessie Willard. Dimensions of open book sans card cover: 23.5 x 34.5 cm from: PhotoSeed Archive

In 1897, one of the very first Kodak international competitions originated in England, which lead to a show known as the Eastman Photographic Exhibition.

Held at the New Gallery on Regent Street in London from October 27 to November 16, 1897, the exhibit drew 25,000 photographic entries from around the world, with $3000.00 in prize money. It was organized by amateur photographer George Davison, (1856-1930) a founding member of the British Linked Ring and Director of the Eastman Photographic Materials Company in England. In America, these annual competitions were promoted by Kodak advertising department manager Lewis Bunnell Jones. And with the known exception of the 1897 show traveling to America in 1898 where it was enlarged and displayed at The National Academy of Design in New York City in January, Jones’ hand became more evident beginning in 1905. At least five years of public exhibitions beginning in 1906, of which the Kodak Competition Souvenir of 1905 is one of the finest records of, was the result:

Under Jones’s autocratic supervision, Kodak’s advertising department devised some of the company’s most legendary campaigns and strategies, including the 1893 introduction of the Kodak Girl in magazine ads and posters; the Traveling Kodak Exhibitions that toured the country between 1905 and 1910; the famous “yellow box” packaging in 1905… “(4.)

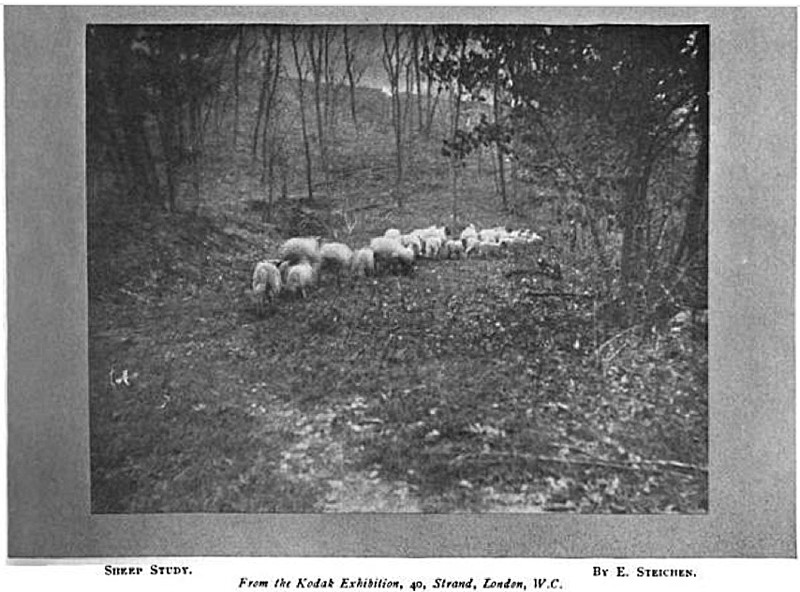

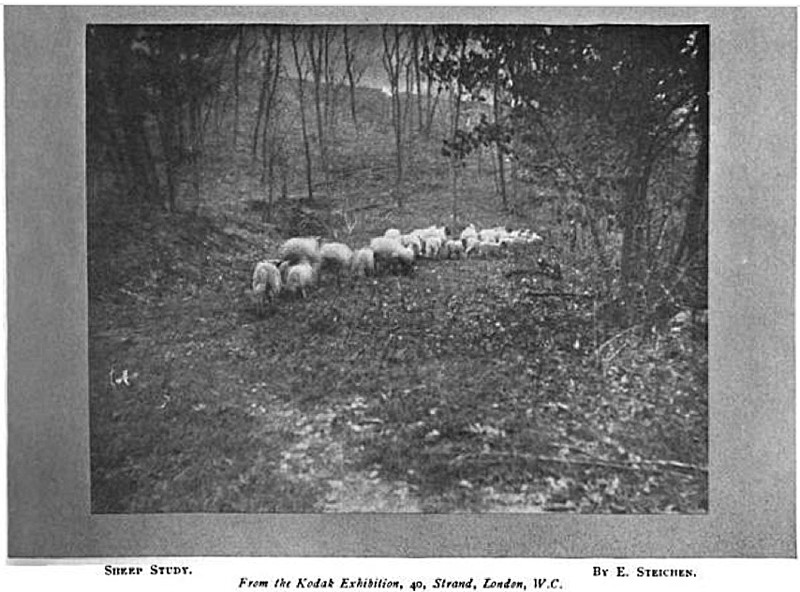

Edward Steichen won 2nd prize and $100.00 in the Class C open category for enlargements for this photo titled “Sheep Study”. This halftone version from the enlarged exhibited print was reproduced in London’s Amateur Photographer in August, 1907. Compared to the more commonly known version by Steichen’s hand, a hand-toned photogravure published in Camera Work XIX, this image is practically “straight”. The editors however make their feelings known it does no justice to his original intent: “In the second place, the pictures are not the original prize-winning prints, but enlargements made at the Company’s English works; and however skilful the enlarger is, he cannot possibly always catch and elaborate the ideas of men like Steichen. Bearing this in mind, it is easy to imagine the beauty of Steichen’s own enlargement of the “Sheep Study,” No. 1, with the sheep blended into a soft mass of tones”…

Records from primary source material shed light on these competitions, which beginning in 1907 began to be annually known as the Kodak Advertising Contests:

1904:

Book of the £1,000 Kodak Exhibition.

This is the title, stamped in gold, on the cover of a handsome portfolio just issued by the Kodak Press. “To show something of the work that is being accomplished in pictorial photography by the devotees of the Kodak system.” The world-wide interest in the Kodak competition of 1904 naturally brought together much of the best work of the camera and the public exhibition of the competing pictures in London was an eye-opener to all who could attend. From this exhibition sixty or more prints were selected and have been reproduced in half-tone, which will enable photographers in the most remote localities to see the work of others and note the kind and quality of the work which finds favor with competition judges. (5.)

And from The Photographic Times:

A detailed report of the results of the £1,000 Kodak Competition has been received in this country, and the results cannot but prove gratifying to those who take an interest in the advancement of American photography. There were something over 20,000 entries received, of which about 12,000 were from the British Isles, 2,500 from France, 2,000 from the United States, 1,700 from Germany and 2,000 scattering. The British Isles received 229 prizes, the United States 85 prizes, France 28 and Germany 12. It will thus be seen that the British exhibitors received one prize to every 52 entries, the French one to every 89, the German one to every 141 and the American one to every 23 entries. Our American amateurs, in proportion to their entries, carried off over twice as much as their British cousins, three and a half times as much as the French competitors and did six times as well as the Germans—at least such was the opinion of the British judges who were no less personages than Sir William Abney, Mr. Craig Annan and Mr. Frank Sutcliffe. (6.)

Detail: Edward Steichen: “Pastoral – Moonlight” (Camera Work XIX, 1907: 15.6 x 19.9 cm) This blue/green hand-toned photogravure better reflects the intent of Steichen as it is by his own hand- especially when compared to the “straight” version exhibited in London in 1906 as part of the 1905 Kodak Competition. from: PhotoSeed Archive

1905-06

The subject of this post concerns the 1905 Kodak Competition, which concluded the following year in 1906 with public exhibitions in America as well as London, England in 1907.

1907

The 1907 Advertising Contest of the Eastman Kodak Company possessed a far greater value than the securing of good pictures for use in advertising the products of the Eastman Company. Its value from an educational and artistic standpoint is exceedingly great, and of inestimable value to all photographers and illustrators who use other methods than photography. The results of this competition were a revelation as to the possibilities of graphic illustration by means of the camera when handled understandingly.

The pictures possess human interest far surpassing anything that could have been drawn or painted, for the subjects were real live people, and not the imaginative creations of some artistic brain. Such pictures grasp and hold the interest of the reader and, when their story is pleasingly told, are most convincing.

Glance over the advertising section of any of the popular magazines, and see how important a part the camera plays in illustrating and in pictorially clinching the advertiser’s argument. In many instances, the picture has been that of some charming bit of femininity and used often only to hold the attention in order that the accompanying text might be read. (7.)

1908

In 1908, the Eastman Kodak Company sponsored an advertising contest for professional as well as amateur photographers. $1600.00 was offered as cash prizes. Winning submissions would be used to advertise Kodak products. Mrs. W.W. Pearce, an active woman amateur photographer from Waukegan, IL, won first prize and $300.00 in the Class B Amateur class of the contest. The PhotoSeed Archive owns a vintage example of this winning print, and more background on the contest and results from 1908 can be found here.

1909

The contention that better pictures for advertising purposes could be produced by means of photography than by any other artistic method has been still further justified by the result of the 1909 Kodak Advertising Contest.

It is gratifying to note the continued interest of competitors in former contests, and also in highly artistic work submitted by newcomers in the field.

The jury which passed on the work was highly competent, consisting of Mr. Rudolph Eickemeyer, of Davis & Eickemeyer; Mr. A. F. Bradley, ex president of the P. P. S. of New York; Mr. Henry D. Wilson, advertising manager of Cosmopolitan; Mr. C. C. Vernam, general manager of the Smith & Street publications, and Mr. Walter R. Hine, vice-president and general manager of Frank Seaman, Incorporated, one of the largest, if not the largest advertising agency in the United States. Mr. Frank R. Barrows, president of the P. A. of A., was announced as one of the judges, but was unavoidably detained, Mr. Bradley acting in his place. (8.)

1910

THE Eastman Kodak Company, always a most generous patron of photographers, both professional and amateur, has just closed its advertising competition for 1910. This contest has become one of the most important fixtures of the photographic world, not only because of the remarkably large cash prizes awarded, but also because of the tremendous stimulus it has been to the application of photography to advertising. Photo-era has many times called attention to the increasing use of photographs by the general advertiser, and one has only to pick up almost any of the popular magazines and glance at the advertising pages (more interesting, oftentimes, than the body of the letter-press) to see how greatly the ad-writer depends on the halftone cut from a photograph to present his goods in an attractive manner. In this development, beyond question, the Eastman Company has had a large share, and the successful contestants in its contests have gained valuable experience which they can apply with profit, should they so desire, to photographic illustration-work. (9.)

1911

From our standpoint the previous Kodak Advertising Contests have been a distinct and growing success. They have supplied us with pictures that told interestingly of the charm and simplicity of Kodakery. But there has been one drawback. In the professional division (Class A), the prizes have gone so often to the same people that we fear other photographers are likely to be discouraged. In order to remove this possible objection to our contests, these former winners will be barred from participation in Class A in the 1911 competition. (10.)

1913

1913 Kodak Advertising Contest — $3,000.00 In Cash Prizes.— The Kodak Advertising Contests are not for the purpose of securing sample prints. They are for the purpose of securing illustrations to be used in our magazine advertising, for street car cards, for booklet covers and the like.

We prefer photographs to paintings, not only because they are more real, but also because it seems particularly fit that photographs should be used in preference to drawings in advertising the photographic business. The successful pictures are those that suggest the pleasures that are to be derived from the use of the kodak, or the simplicity of the kodak system of photography — pictures around which the advertising man can write a simple and convincing story. Of course the subject is an old one — therefore the more value in the picture that tells the old story in a new way. Originality, simplicity, interest, beauty—and with these good technique —are all qualities that appeal to the judges.

In addition to the prize pictures we often purchase several of the less successful pictures for future use in our advertising. So it will be seen that in reality our prize money is even bigger than we advertise.

There is a big future for the camera in the illustrative field. There’s a growing use of photographs in magazine and book illustrations, to say nothing of the rapid advance along the same lines in advertising work. There’s a constant demand for pictures that are full of human interest. Such are the pictures that we need, that others need. The Kodak Advertising Contests offer an opportunity for your entry into this growing field of photographic work. (11.)

Detail: platinum print: “Threading the Needle”, (12.4 x 9.9 cm | 11.7 x 9.2 cm) by Nancy Ford Cones (American,1869-1962) This photograph, printed on Kodak’s WD Platinum (water-development) paper, and featured in the 1905 Competition Souvenir book, won the $100.00 second prize for Cones in the Class A Open category, featuring negatives 3 ¼ x 4 ¼ or larger in size. Cones was born in Milan, Ohio but is listed as being from Covington, Kentucky when the photo was taken. from: PhotoSeed Archive

The 1905 Competition might certainly be considered key in launching the careers of many serious amateurs, and it undoubtedly gave others the opportunity to pursue photography professionally as a career:

The Kodak Competitions which have been held during the past six or seven years have been something of a revelation in that they have shown that a very large proportion of those amateurs who take photography seriously are frequent users of the Kodak. The same names that appear as Salon Exhibitors have appeared in the Kodak prize lists and often times the pictures that have hung on the Salon walls were from the same negative that won cash and honor in the Kodak competition. (12.)

Doing the Rest

Similar to celebrity endorsement today, Kodak had the uncanny ability to associate the big photographic names of the early 20th century; including Stieglitz, Steichen and Brigman, with the idea amateur photographers using their products could become as skilled or famous. The often mocked Kodak mantra of “you press the button and we do the rest”-acknowledged even by someone as famous as Stieglitz himself -is ironically shot down when it is learned Kodak made the enlarged prints from competitor’s negatives for exhibition purposes for the 1905 competition and those following it:

THE Kodak Exhibition, at No. 40, Strand, W.C, will come as a surprise to persons who are only accustomed to the ordinary enlargements of prize-winning photographs which are displayed in dealers’ windows; it will come as a decided shock to those who are wont to ridicule the “you press the button, and we do the rest” method of photography. Out of some twenty-eight thousand prints and enlargements which were submitted to the judges at the latest Kodak competition, some sixty were adjudged prizes varying from one to thirty pounds; and the negatives of these prints, which have become the property of the Kodak Company, have been enlarged into huge enlargements at the Kodak works, and are now on view for all to see.

There are many well-known names amongst the prizewinners—Steichen, Stieglitz, Harold Baker, Mrs. Barton, Miss Annie Brigman—but these only made the exposures and developed the negatives, Kodak has done the rest, and, as a rule, Kodak has done it uncommonly well. It is not, of course, to be imagined that the Company’s enlargements of negatives by such individual workers as Steichen and Stieglitz are similar to the results that these men would have themselves obtained, but the wonder is that the work has been done so well. The enlargements of Stieglitz’s negatives are particularly good, especially that of “Soap Bubbles,” No. 7, in which the feeling of light and atmosphere has been successfully maintained; and those subjects in which the figures are lit from behind, and, so to speak, silhouetted against the light, are not easy to handle. …

In considering the question of the awards, two facts must be borne in mind: in the first place, the judges in this particular competition belonged to the American school of photography, and the present tendency of this school is to ascribe great merit to original and beautiful schemes of natural outdoor lighting; and therefore we find Steichen’s tour de force, “Mother and Child,” No. 60, awarded the first prize in Class A; and photographs taken against the light have scored throughout. However, such subjects are undoubtedly beautiful, and the rendering of true values in such subjects is exceedingly difficult, and therefore the attitude of the judges is comprehensible. In the second place, the pictures are not the original prize-winning prints, but enlargements made at the Company’s English works; and however skilful the enlarger is, he cannot possibly always catch and elaborate the ideas of men like Steichen.

Bearing this in mind, it is easy to imagine the beauty of Steichen’s own enlargement of the “Sheep Study,” No. 60, with the sheep blended into a soft mass of tones; and the above-mentioned “Mother and Child” (with the imperfections in the values of the child’s hand corrected during the enlargement) must have been quite good in the original; Stieglitz’s “Bubbles,” No. 7, however, has lost but little through enlargement, and although Stieglitz would probably have rendered the subject in a higher key, the Kodak work is excellent.

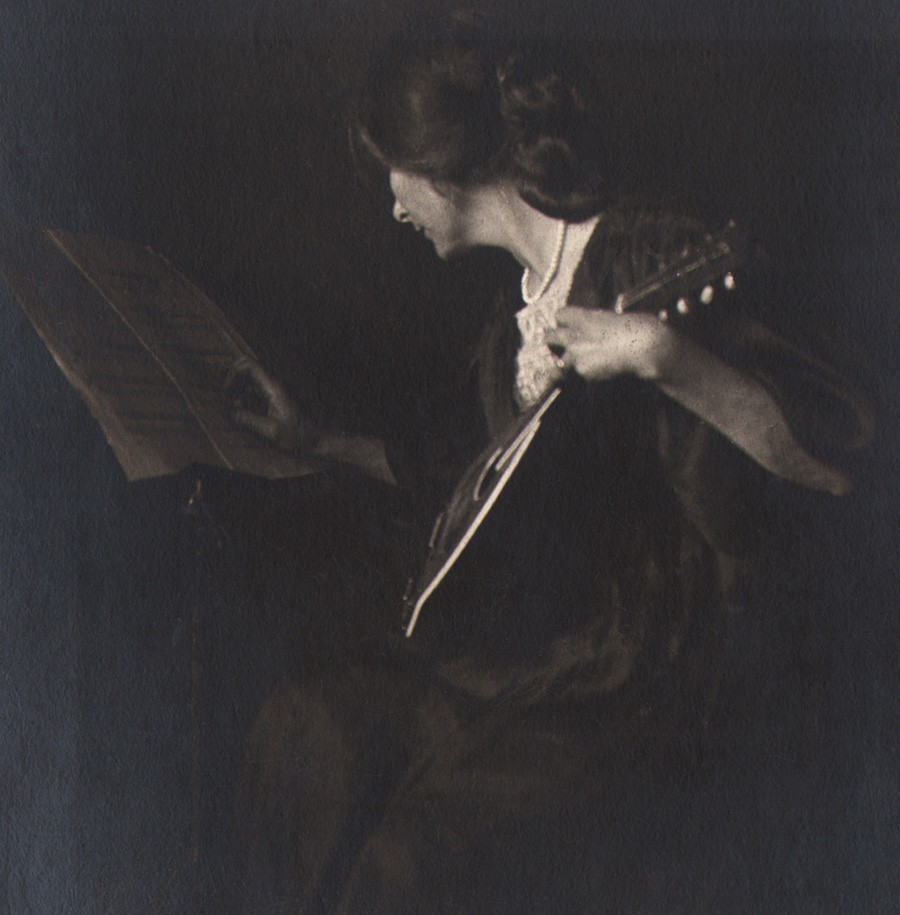

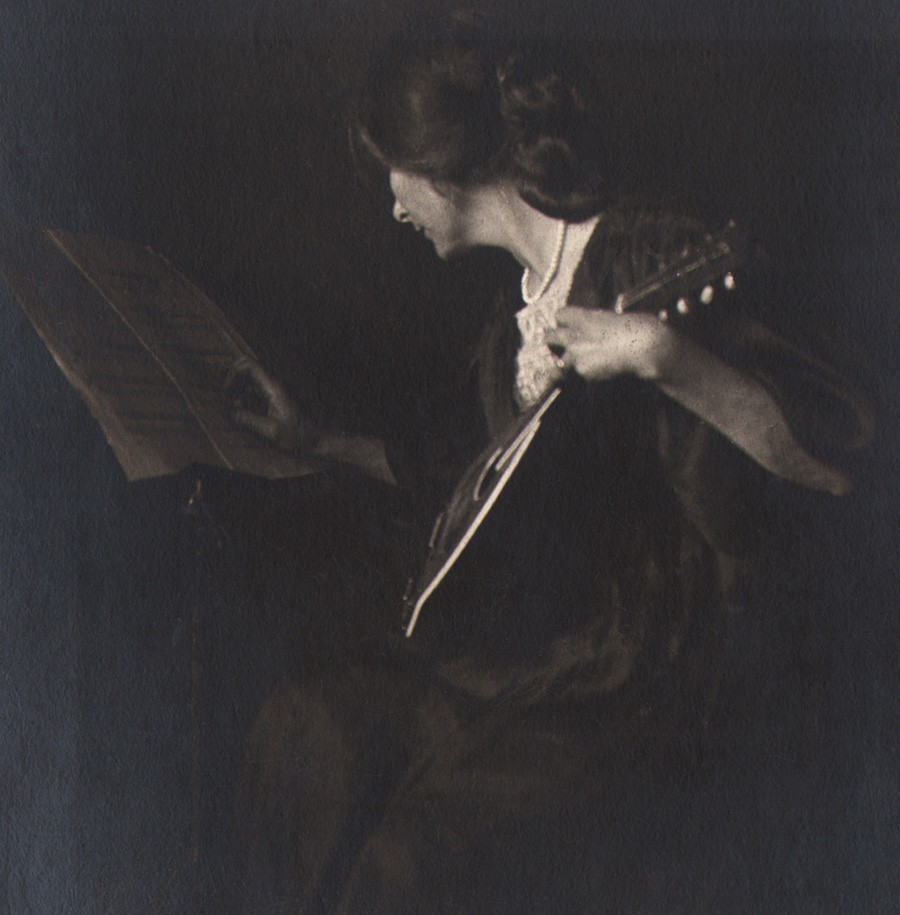

Why has not Miss Annie Brigman’s “Melody” (15) secured a first prize? It is certainly one of the gems of the collection, and it is good throughout, from the posing and lighting of the hand which holds the mandolin, to the subdued lighting of the music illuminated only by the light reflected from the face of “Melody.” Possibly the judges may have considered the lighting, which might have been arranged by Rembrandt himself, somewhat artificial; but there is no doubt that European judges would have thought differently. This picture, taken with a Kodak, enlarged on Kodak bromide paper, by the Kodak Company, is one of the finest pictures ever rendered by the camera. (13.)

Detail: gelatin silver print: “Melody”, (16.4 x 11.2 cm | 15.7 x 10.6 cm) by Anne Brigman (American, 1869-1950) This photograph, which a critic in London’s Amateur Photographer journal in 1907 proclaimed “One of the finest pictures ever rendered by the camera” is printed on Kodak’s Carbon Velox paper, and featured in the 1905 Competition Souvenir book. It won an honorable mention and $20.00 for Brigman in the Class C Open category for Enlargements. The photo is also known as “Woman with Mandolin” from: PhotoSeed Archive

Notes

1. excerpt: Judges for the Kodak Contest: Kodak Trade Circular: Toronto, Canada: April, 1905

2. Ibid: Kodak Trade Circular: December, 1904

3. Camera & Dark-Room: Edited by J.P. Chalmers: New York: January, 1905: p. 30

4. excerpt: A Short History of Kodak Advertising 1888-1932: Kodak and the Lens of Nostalgia: Nancy Martha West: The University Press of Virginia: 2000: p. 27

5. excerpt: Book of the £1,000 Kodak Exhibition: The Camera and Dark-Room: New York: January, 1905: pp. 29-30

6. excerpt: £1,000 Kodak Exhibition: Notes, News & Extracts: The Photographic Times: New York: September, 1904: p. 426

7. excerpt: The Kodak Advertising Contest: The Photographic Times: May, 1908: p. 154. The top prize of $1000.00 was awarded to E. Donald Roberts of Detroit.

8. excerpt: AWARDS, PROFESSIONAL CLASS, 1909 KODAK ADVERTISING CONTEST: Wilson’s Photographic Magazine: New York: January, 1910: p. 46

9. excerpt: The Eastman Advertising-Competition: Malcolm Dean Miller: Photo-Era: Boston: January, 1911: p. 73

10. excerpt: With the Trade: 1911 Kodak Advertising-Contest: Photo-Era: Boston: March, 1911: p. 157

11. excerpt: Our Table: American Photography: Boston: May, 1913: pp. 311-312

12. Advertisements: Eastman Kodak Company: excerpt: The New Competition: The American Amateur Photographer: New York: Jan-Dec. 1905

13. excerpt: The Kodak Picture Exhibition: The Amateur Photographer: London: August 27, 1907: pp. 200-01