“Liberty cannot be preserved without a general knowledge among the people.”

– John Adams

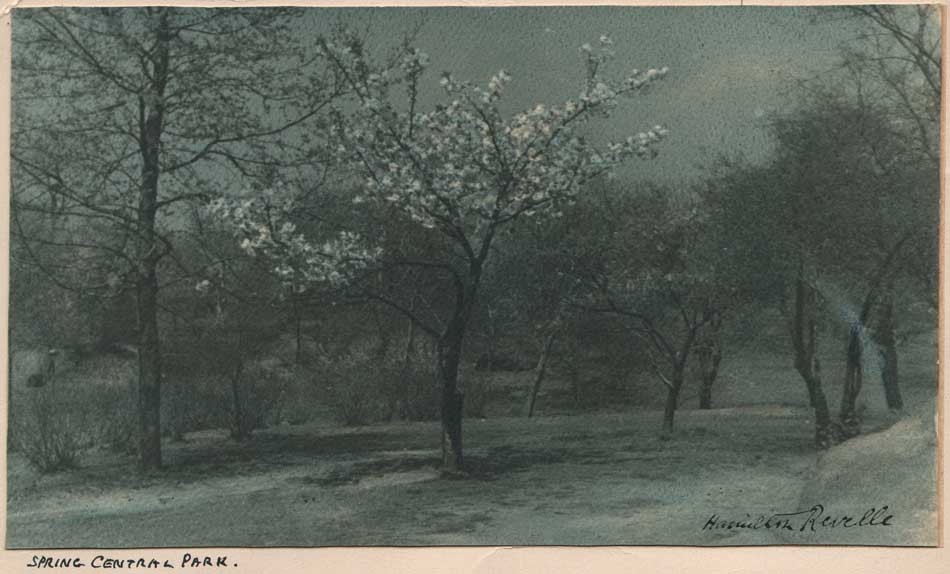

“First Balloon Flight Under the American Aero Club”: 1906: James H. Hare: British: 1856-1946: Chloride print (POP) 17.05 x 12.05 | 17.6 x 12.8 cm: With a crowd looking on including officers, cadets and scientists, French aeronaut Charles Levee is seen ascending in the balloon “L’Allouette” from the siege battery at West Point Military Academy in New York State on Sunday, 11th February, 1906. This is the original photograph taken by pioneering British photojournalist Jimmy Hare of the ascent, which was published for his employer Collier’s Magazine on 24th February of that year. The fledgling American Aero Club, based in New York City, hired Charles Levee to pilot their 28′ diameter yellow balloon, which took 12,500 cubic feet of coal gas to inflate according to a New York Times dispatch. “Wearing an ordinary Winter overcoat and a close-fitting cap” Levee ascended at 3:55 p.m. in the basket of the balloon made of cotton-fabric (the first time a balloon launched from West Point) and traveled nearly 60 kilometers before finally descending at Hurley, New York at 8:10 p.m. with the aid of a rip cord. from: PhotoSeed Archive

Lately, I’ve become worried about that general knowledge thing. But this is not a lecture, and a new year is upon us, so bear with me here. Late this summer, I came full-circle back to my native New England after retiring from a 30-year run wearing the hat of photojournalist for newspapers across the country. Photographing and sharing the stories of people from literally all walks of life has been my best teacher and given me the most valuable education and perspective I could ever hope for in my career: the nuance of which I often find lacking in the public discourse of late rising from these so-called divided States of America.

The Minute Man Statue: ca. 1900: by unknown photographer working for Detroit Photographic Company: Photochrom: from album (29.0 x 40.0 cm) of 48 Photochroms depicting mostly New England historical places and views prepared by the Detroit Photographic Co. for use as a catalog in their offices. Statue in bronze by American sculptor Daniel Chester French (1850-1931) dedicated on the centenary of the Battle of Concord on 19th April, 1875: During the first battle of the American Revolutionary War, which took place here at The Old North Bridge on the 19th of April, 1775 in the town of Concord, MA, (then located in the British Crown colony of the Province of Massachusetts Bay) a group of 37 Acton, MA Minutemen led by Captain Isaac Davis (b. 1745) faced off (with other militia companies made up of about 500 men) against 100 British “Regular” troops. Davis was the first casualty at the bridge during the American War of independence, with Acton Minuteman Abner Hosmer, (1754-1775) a private who played his drum into battle as company musician, the second mortally wounded after being shot through the head. (Acton Minuteman James Hayward also died later that day) On the base of this statue are inscribed the first stanza of American poet Ralph Waldo Emersons Concord Hymn from 1836:”By the rude bridge that arched the flood, Their flag to Aprils breeze unfurled, Here once the embattled farmers stood And fired the shot heard round the world.” Said to be modeled after Captain Davis but also known to have been done from live models posing in the studio of sculptor Daniel Chester French, the Minute Man statue proudly shows the enduring American spirit during the nations struggle for freedom and independence. from: Library of Congress: Call Number LOT 12003, p. 30.

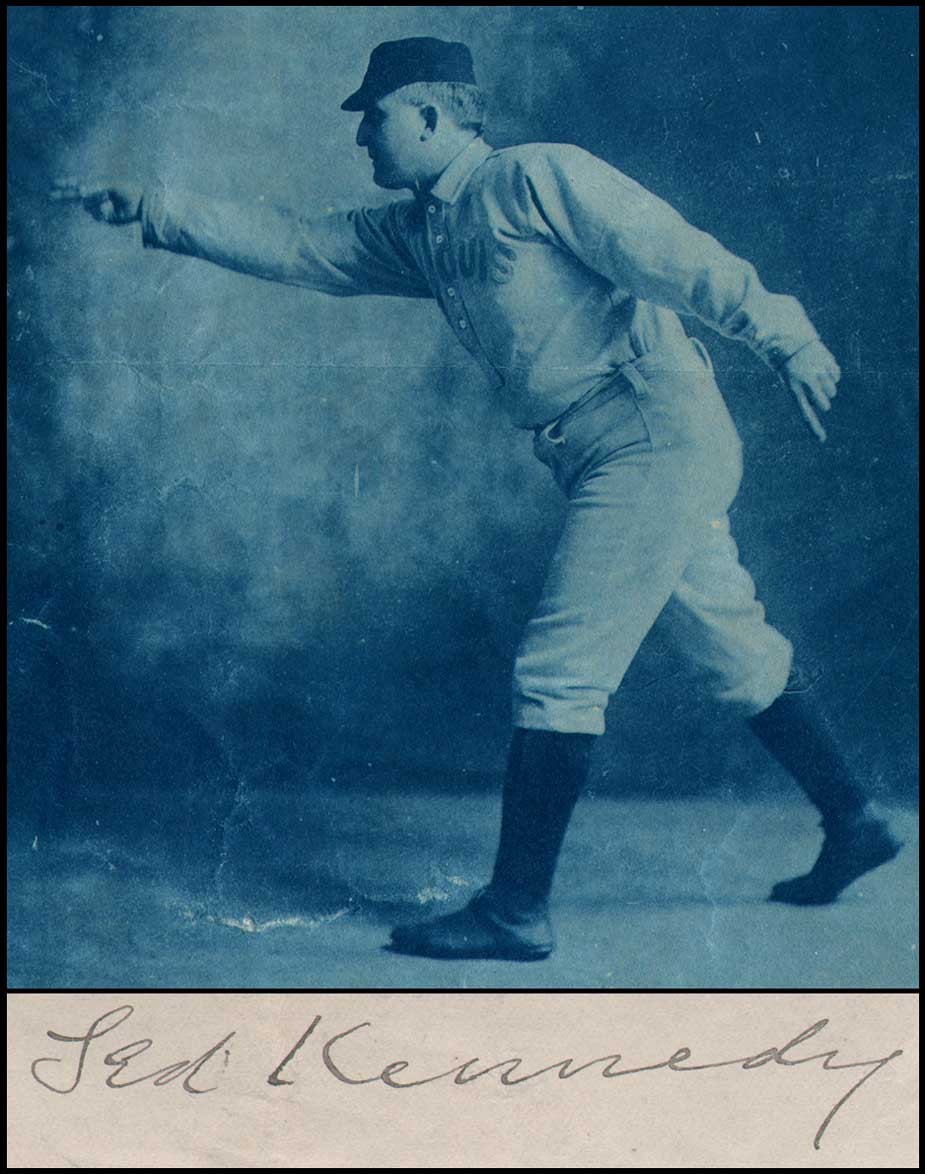

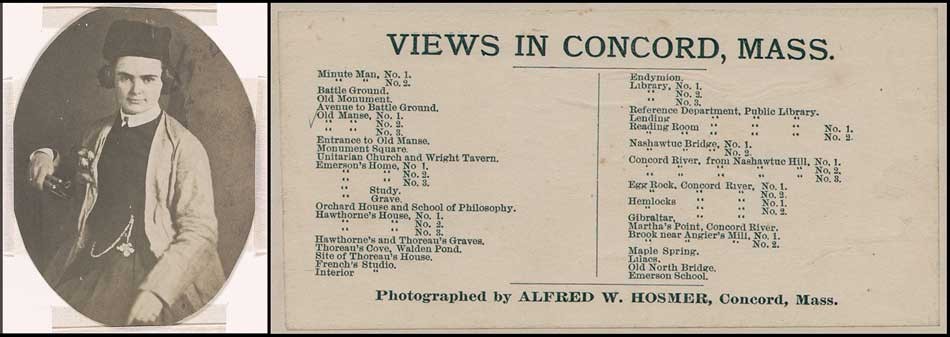

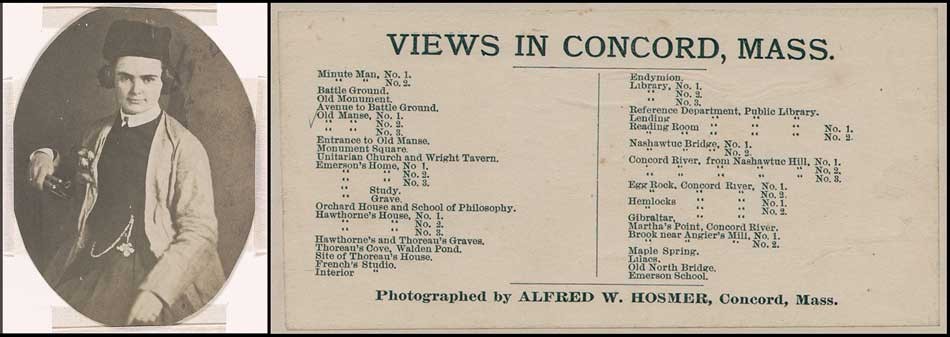

Detail: “Old Manse, No. 3” from: Views in Concord, Mass.: ca. 1885: Alfred Winslow Hosmer, American (1851-1903) Pasted Albumen print on oversized cabinet card with gilt edging: 11.2 x 19.8 | 18.1 x 21.4 cm: Approximately 110 years later, another Hosmer descendent to Private Abner Hosmer, the photographer Alfred Hosmer, photographed scenes in and around Concord like this one for sale as souvenir keepsake cabinet cards of battleground scenes and places, including the Minute Man statue. This view, showing the stately pile The Old Manse, was built in 1770 for the Rev. William Emerson, (1743-1776) whose family witnessed the battle at the Old North Bridge of 19th April 1775 from the upstairs windows of the home. Later, Emerson’s grandson, the acclaimed Transcendentalist writer Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882) lived in the home and later wrote his Concord Hymn of 1836 as referenced previously in this post. The photographer Alfred Hosmer, whose surviving archive of over 800 glass plate negatives is housed at the Concord (MA) Free Library, is also significant, according to the library, for “his role in establishing Henry David Thoreau’s reputation as a major American author. He was one of the earliest admirers and promoters of Thoreau’s life and writings. He expressed his sympathy with and interest in Thoreau through his own first-hand observations of the flora and fauna of Concord, his Thoreau-related photography, his correspondence with other Thoreau enthusiasts, and his active collecting of Thoreauviana.” From: PhotoSeed Archive

“Witness to a Revolution” (American): 2015: David Spencer for PhotoSeed Archive. With Mount Monadnock just off to the west, the waning light of day washes over the white clapboard siding of the Original Meeting House for the Town of Jaffrey, New Hampshire. Erected in 1775 only two years after the town’s incorporation and after American Minutemen first began their armed fight with the British at Concord and Lexington, tradition states the frame of the structure was raised on Saturday, June 17th of that year, with workers recounting they heard booming cannon fire 70 miles east in Boston which they learned the next day was the Battle of Bunker Hill. Originally used by Congregationalists for church services and town business, worship took place here until 1844. The town website gives a few more details: “In 1822, the bell tower and spire were added, paid for by donations on the condition that the Town would buy the bell, which it did the following year. It was cast by the Paul Revere Foundry.”

But I’m only one person, what can I do about it but spout a bunch of words? Photography of course. The so-called Universal language. Like everyone’s favorite sports team. Surely one can have opinions concerning old photographs? I’m betting yes and I hope you will.

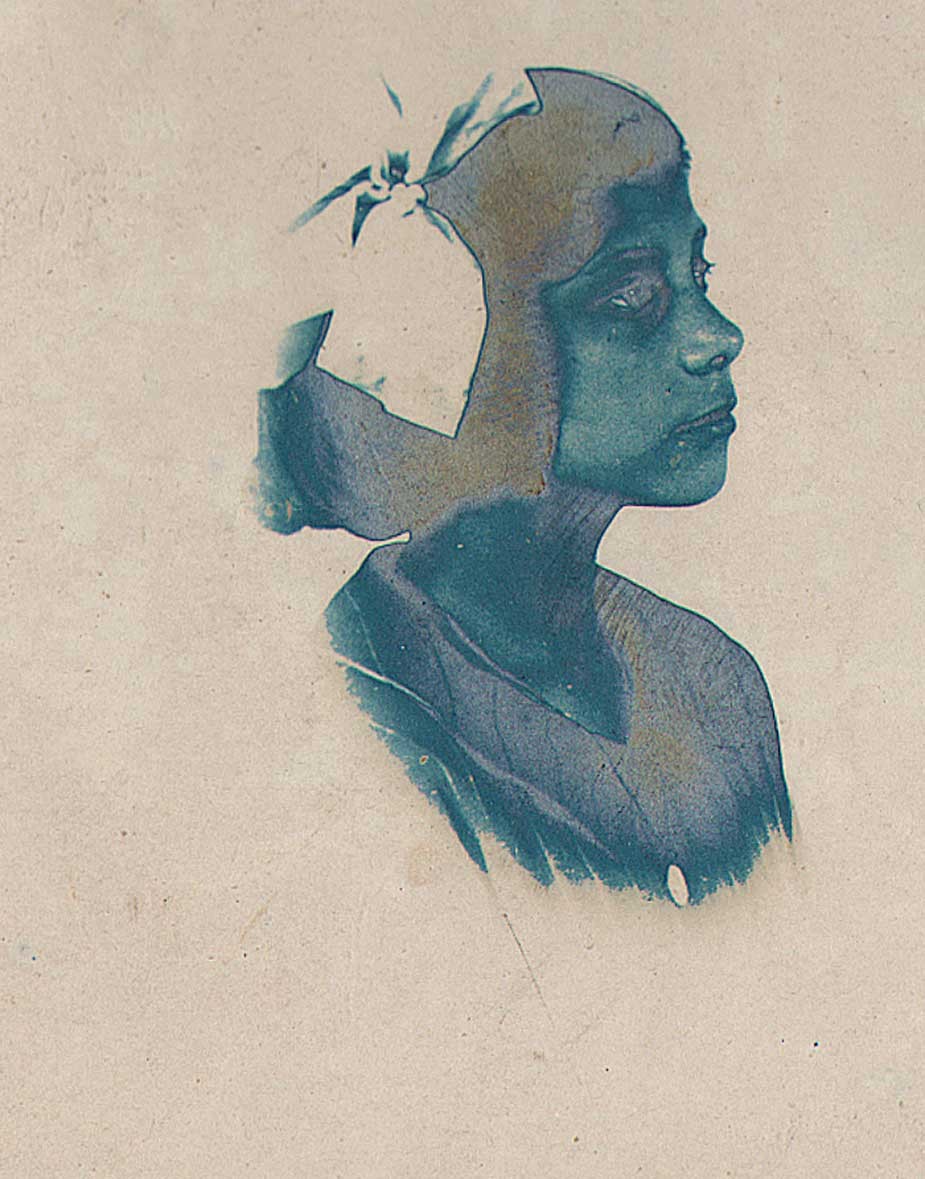

Detail: “Aunt Ward”: ca. 1890-1900 : Attributed photographer: Charles Rollins Tucker, American (b. 1868): mounted brown-toned gelatin silver or albumen print on oversized card: 11.1 x 18.4 cm | 20.4 x 25.5 cm. Believed to have been taken in Massachusetts, and with cane firmly held in elderly hand, this unknown “Aunt Ward”, who was a blood relation to the photographer, can be seen standing in threshold at center, could rightly epitomize the hardscrabble resourcefulness of a typical New England Yankee before all the modern benefits of the late 20th Century Industrial Revolution kicked into high gear. At the front of her weather-beaten Cape Cod style dwelling can be seen a trusty ladderback garden chair parked to the left of the doorway as well as wooden gutters overhead leading to large rain barrels front and back and anchored from behind at far left by a shingled outhouse. From: PhotoSeed Archive

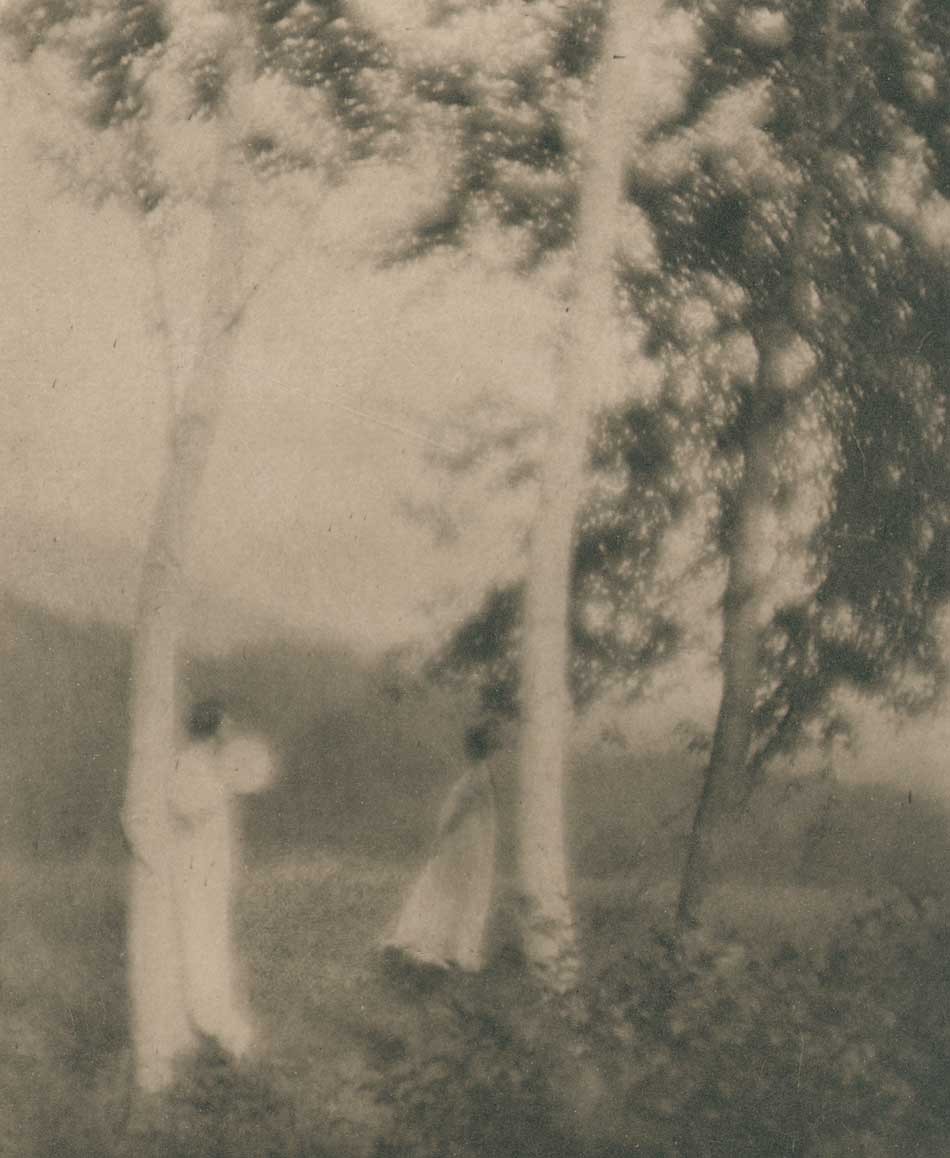

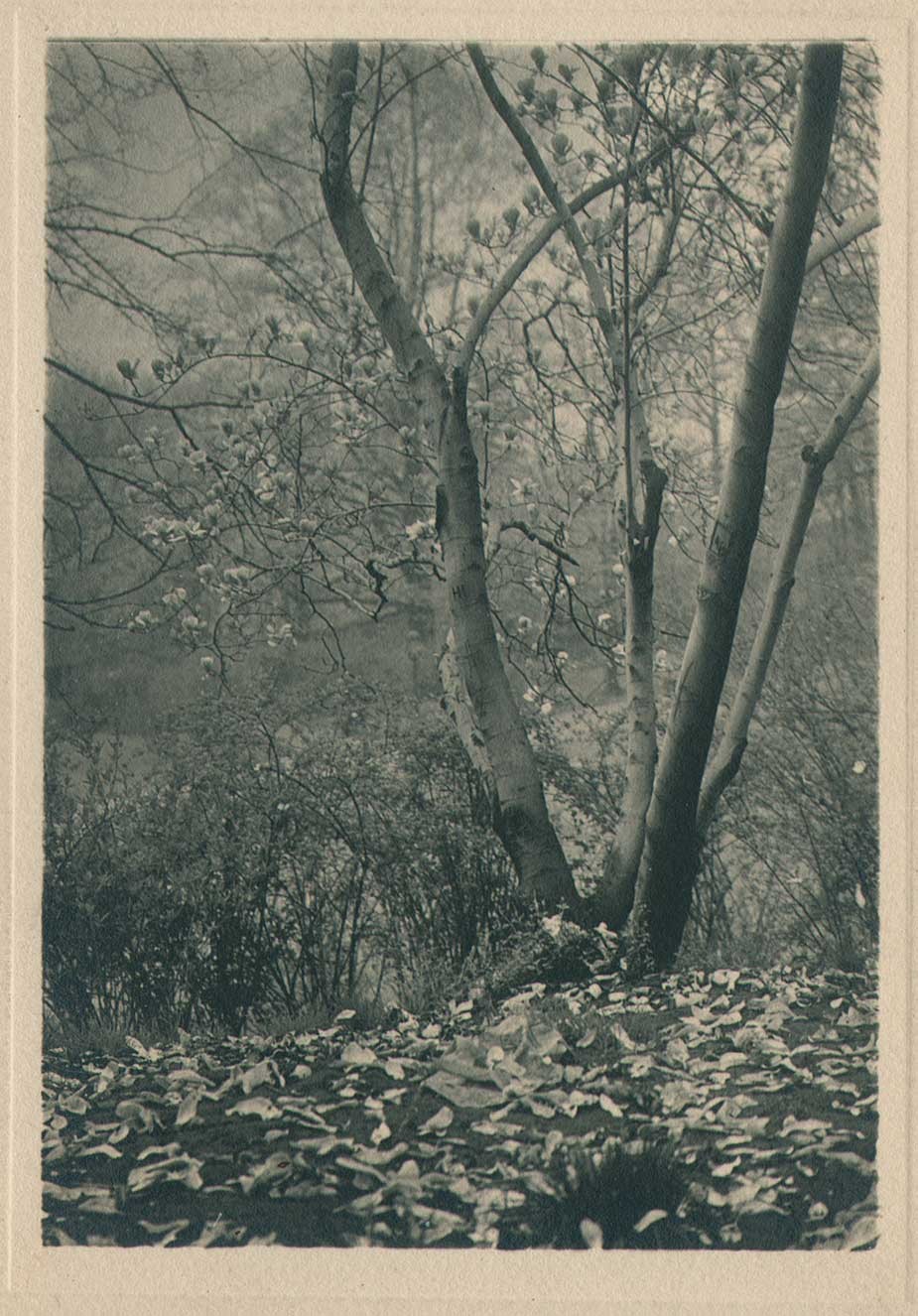

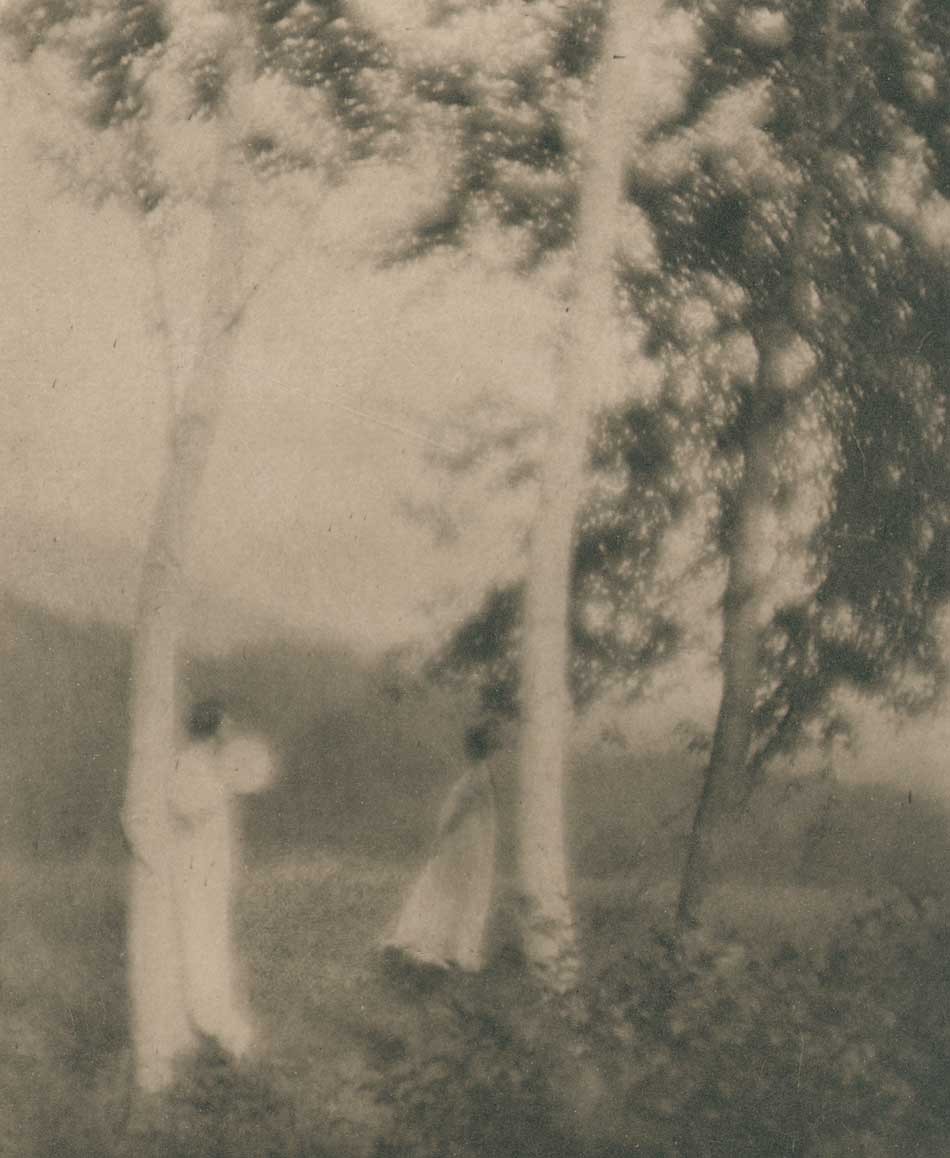

Detail: “VII. White Trees”: 1910: George H. Seeley, American (1880-1955) : hand-pulled Japan-paper tissue photogravure by the Manhattan Photogravure Co. included with Camera Work issue XXIX:full image: 19.9 x 15.7 cm: Amateur photographer and painter George Henry Seeley, a native of Stockbridge, Massachusetts, made his living as supervisor of art for his local school district. In order to take full advantage of the showy beauty of the Berkshire region with a hint of the Taconic mountain range seen in the distance, he positioned his sisters in this plein air allegorical composition, with the trunk and back of a white birch tree (Betula papyrifera) anchoring this triangulated landscape at left. From: PhotoSeed Archive

And photographic puns besides the point, I’ve learned there is no such thing as black and white-especially concerning peoples lives and how those lives are lived. Speaking of that aforementioned questionable public discourse, I’m more of the belief life is all about colorful nuance, and unless you have walked a mile in someone’s shoes, as my mother would say, what do you really know to be their reality and truths?

Hosmer & Sculpture: Left: Portrait of sculptor Harriet Goodhue Hosmer (1830-1908): by Frederick DeBourg Richards, American (1822-1903): ca. 1850-60: salted paper print on card mount ; photo (oval) 15.7 x 12.1 cm, on mount 35.5 x 27.9 cm: Considered the most distinguished female sculptor in America during the 19th century, and working in the neoclassical style, Harriet Hosmer clutches her sculpting tools seen at far left while wearing her artist’s smock in this portrait probably taken in Rome, Italy. Born 50 years earlier than photographer and painter George Seeley, Hosmer finished her early education just north of Seeley’s Stockbridge in the town of Lenox, completing a course of study at Elizabeth Sedgwick’s School for Young Ladies before learning disciplines including rowing, skating and riding. With an interest in anatomy at a young age spurred by her father Hiram’s occupation as a physician, her artistic skills began to take form after she took private lessons when only 20. {Women were not allowed to attend medical schools during that time.} She decided to to travel to Rome to further hone her skills and quickly made a name for herself there, receiving her first commission in 1856. Many of her works survive, including a marble sculpture of Puck (Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, CT) and a towering 10′ likeness in bronze of Missouri Senator Thomas Hart Benton dedicated in 1868 (recently refurbished) and located in Lafayette Park in St. Louis. Of this gender-breaking artist, Hosmer’s friend Elizabeth Barrett Browning described Harriet as “a perfectly emancipated female.” from: LOC Call Number: LOT 14120, no. 20. Right: pasted paper label: “Views in Concord, Mass.” ca. 1885: on verso of oversized cabinet card “Old Manse, No. 3”: Photographed by Alfred W. Hosmer, Concord, Mass. label: 7.0 x 14.4 cm; card: 18.1 x 21.4 cm. Born 20 years after his cousin Harriet Hosmer, Alfred Winslow Hosmer (1851-1903) also had a connection with sculpture via his friendship with fellow Concord, Mass. resident and sculptor Daniel Chester French. French, whose first major commission was the Minute Man statue outlined in this post, also had his Concord art studio photographed by Hosmer, with several cabinet card views including French’s life-size nude sculpture of the Greek mythical male shepherd Endymion listed here for sale. From: PhotoSeed Archive

Through the platform of this website, I hope truth and reality of our shared photographic artistic past are presented with enough facts and context to make a difference. I’m hoping conversations will develop because it exists, and they will be shared in some fashion. Facebook likes, page views, and the latest and greatest apps don’t really concern me here. Instead, just about everything you see will be estate fresh, so dig in and have fun.

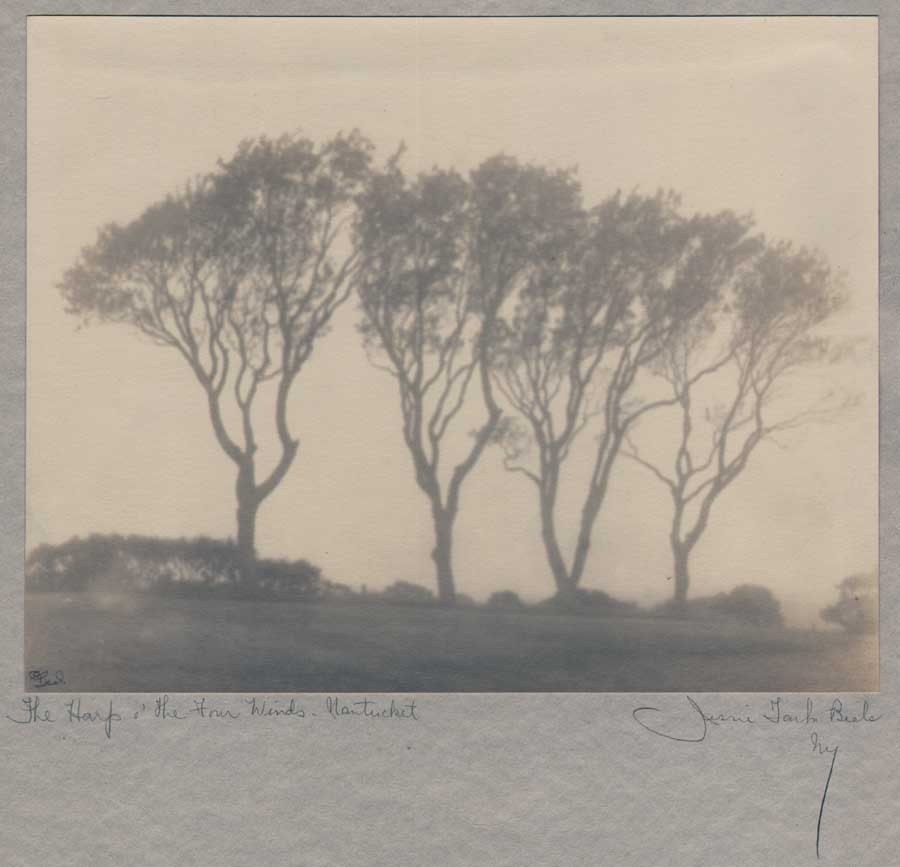

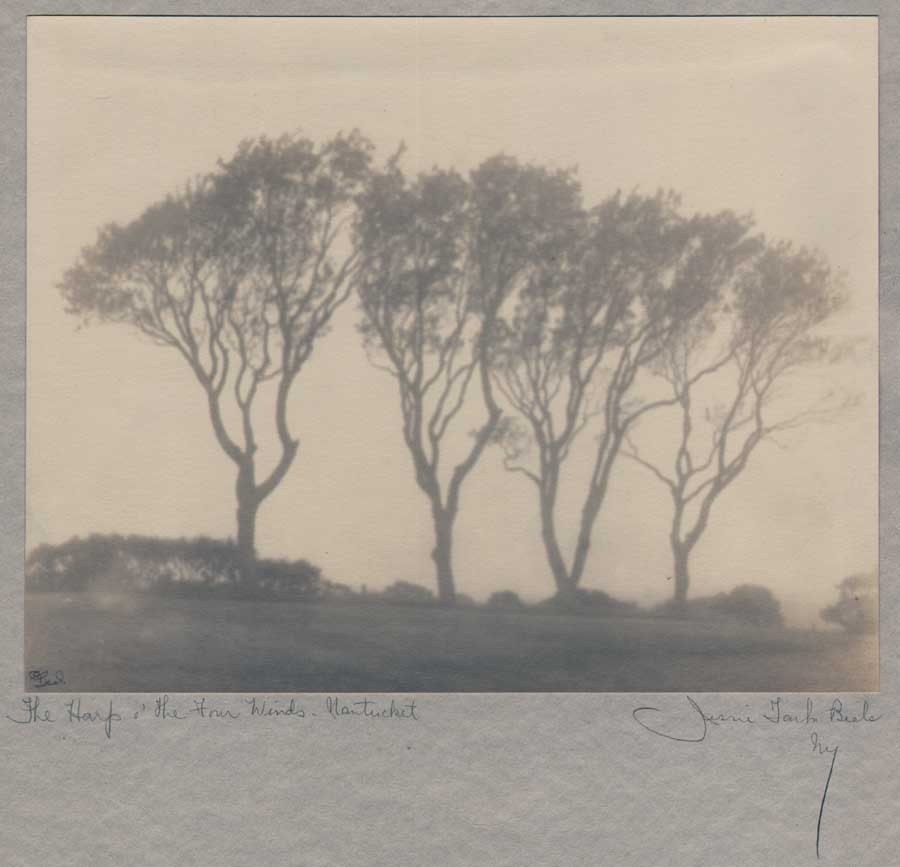

The Harp o’ The Four Winds-Nantucket: Jessie Tarbox Beals, American, born Canada: (1870-1942) Gelatin silver print ca. 1905-15 (this example 1920-26 when she rented a salon-studio at 333 Fourth Ave. in N.Y.C.): 19.0 x 23.9 | 43.1 x 28.2 cm : Although not a New England native like Harriet Hosmer, Jessie Tarbox Beals was also groundbreaking for her gender, and is credited as being the first female photojournalist. New England and Massachusetts however played formative roles in her life. According to a short biography provided by the New-York Historical Society, which holds an extensive archive of Beal’s work, Jessie was only 17 when she moved to Williamsburg, Mass from Hamilton, Ontario to join an older brother. There, her first job was teaching “seven pupils in a one-room schoolhouse for $7 a week”… later, she became interested in photography the following year in 1888 after acquiring her first camera in a magazine contest. Shortly, she became a professional after investing “$12 and bought a Kodak camera, with which she established a photo studio on the front lawn of her home. Local residents came to have their portraits taken, or to ask for pictures of their houses and other possessions. Beals was aided in her commercial endeavors by groups of Smith College students, (from nearby Northampton-ed) who wanted pictures to be made of their parties and picnics. By the end of two summers she was making more money taking photographs than teaching school.” This example of Beal’s landscape work was taken in the Bay State in Nantucket, a 1920 caption in the New York Tribune for it stating: “An early morning camera symphony–the Harp o’ the Four Winds, Nantucket, Mass., at 5 a. m.” From: PhotoSeed Archive

With mountains now in my backyard instead of the view of corn as high as an elephant’s eye from my last Midwest home, I’ve been thinking of late of the early ancestors and the roles they took-small but significant- in shaping from these parts an America I’m proud to call home.

Let me state off the top that my forebears did not come from money. Instead, other than the constant role of being soldiers in America’s early fight for Independence, they were hardscrabble Yankees: industrious farmers, deacons, bricklayers and later in the 19th century, stonemasons.

Left: American Revolutionary War Brigadier General John Stark (1728-1822) points the way at the base of the Bennington Battle Monument in Vermont. 2016: David Spencer for PhotoSeed Archive. On August 16, 1777, approximately 2,000 militia members led by John Stark soundly defeated British General John Burgoyne’s army made up primarily of Hessians during the Battle of Bennington at Walloomsac, New York. Although the battle lead to Burgoyne’s eventual surrender at Saratoga and “galvanized colonial support for the independence movement” (Wikipedia) the battle was not without 30 militia causalities, including 17-year-old Jonathan Hosmer, Jr., (1760-77) the second Hosmer to die in the American Revolution after his uncle Abner nearly two years earlier at Concord. Right: “The Connecticut”: 1897: Charles Rollins Tucker, American (b. 1868): albumen print : 12.4 x 17.6 cm | 16.6 x 21.4 cm: Besides being a primary inland navigational route used extensively by Native American tribes hundreds of years before European colonization, the Connecticut River and its watershed encompassing the fertile Connecticut River Valley remains largely responsible for the regions continued development. This longest of New England rivers not only continues to fuel agriculture on a large scale but beginning in the late 20th Century, with its’ large number of waterfalls, provided plenty of factories situated along its’ banks the energy needed to power the Industrial Revolution, with the cities of Hartford, Conn. and Springfield, Mass being two of its most prominent to gain population and prominence. From: PhotoSeed Archive

But like all families that have been here a while, I also have several relatives I’m quite certain are famous, and am most proud to say even significant. For details, please consult the small print under the respective photographs in this post for Private Abner Hosmer, an 18th Century Concord, Mass. Minute Man and Harriet Goodhue Hosmer, 19th Century groundbreaking American female sculptor.

The Hosmer’s & the Great Migration

The ancestors on my mother’s side, the Hosmer’s of Hawkhurst, Kent in England, were part of the so-called Great Migration. I’m now counted as a 12th generation Hosmer descendant, the first landing on these shores being James Hosmer, (b. 1605) a clothier who made the ocean voyage to the new world with his family aboard the good ship Elizabeth of London in April of 1635. They called themselves Puritans and were seeking religious independence from the Crown. (Charles I) It might have stopped there, and I for one am ever grateful it didn’t, because James’ wife Ann and two young daughters died during the trip or shortly after they arrived and settled in Cambridge in the Massachusetts Bay Colony. He remarried however, twice again due to death from disease in this new world, and went on to become one of the founders of Concord, Mass. two years later in 1637, where he made his living laying out grants of farmland and later serving as town selectman in 1660.

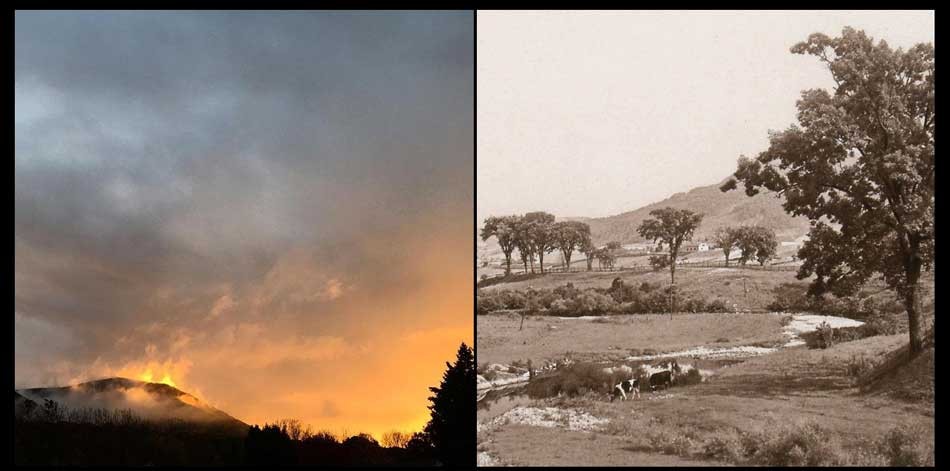

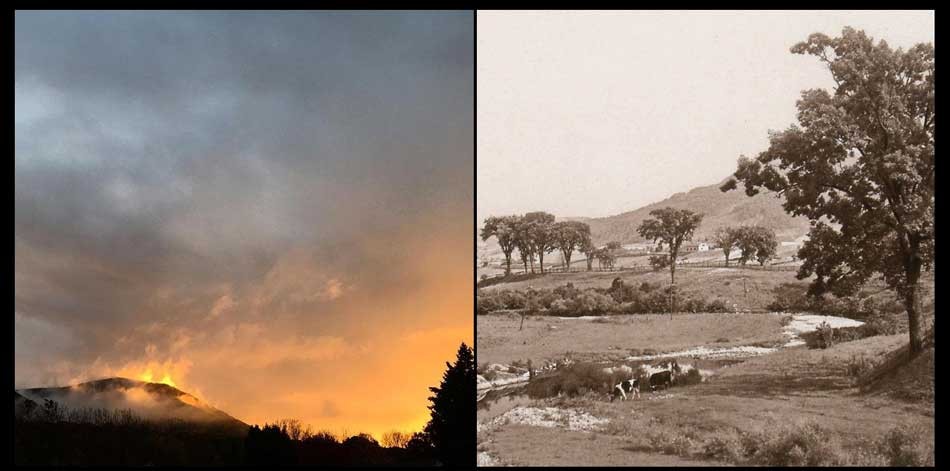

The Berkshires: Modern & Vintage: Left: “Sunset Glow over Mount Greylock State Reservation”: by Shannon O’Brien: North Adams, Mass: Fall, 2016 (iPhone): Right: Detail: “Williamstown Hills, Williamstown” (Looking toward North Adams) “The encircling hills of Berkshire.” : Arthur (Wentworth) Scott, American: 1899: hand-pulled photogravure plate included in volume: Nature Studies in Berkshire by John Coleman Adams published by G.P. Putnam’s Sons: In the volume’s introduction, “Our Berkshire” Coleman Adams sets the stage for the reader: “To know Berkshire is to love it. To love it is to feel a sort of proprietorship in it, a pride in its glories, a joy in its beauties, such as owners have in their estates and patriots in their native land. He who was born here clings to the soil if he stays, or reverts to it if he moves from it, with a New England steadfastness as intense and deep as a moral principle.” (p. 3) From: Archive.org

“Fall & First Snow: Williamstown”: 2016: David Spencer for PhotoSeed Archive (iPhone)

As a native of the Nutmeg state, I’m now proud to hail from the Bay state in the Berkshire Hills. Time and inclination willing, there will be many more photographic treasures from the past displayed for public consumption on PhotoSeed, as well as the planned rollout in the coming year-finally-of PhotoSeed Gallery, an e-commerce platform through Shopify selling vintage work. As your intrepid explorer and guide, I hope to present you with something worth thinking and conversing about in the new year and beyond.

-David Spencer-

“Williams Door”: Frances and Mary Allen, American: ca. 1895-1905: Platinum print: 20.2 x 12.7 cm: Made from native old-growth, eastern white pine, this view shows the Connecticut River Valley Doorway built by joiner Samuel Partridge which graces the front of the John Williams house in Old Deerfield Village, Mass. The home, and doorway, (since removed in 2001, placed on display and replaced by a reproduction) is named for the Rev. John Williams (1664-1729) in the village, and is now owned by Deerfield Academy. (the door is featured in the private school’s seal) Rev. Williams was “a New England Puritan minister who became famous for The Redeemed Captive, his account of his captivity by the Mohawk after the Deerfield Massacre during Queen Anne’s War.” (Wikipedia) Working in the pictorial photographic style at the end and beginning of the 20th Century, the Allen Sisters of Deerfield did a brisk trade for tourists through their staged genre scenes and colonial views of Old Deerfield, including the Williams door seen here which carries a price tag on the verso of .50 cents. The home was originally built in 1760 by the Rev. Williams’ son Elijah Williams, a shopkeeper and tavern-owner. From: PhotoSeed Archive

“Tom and Betty Put the Things on Ammi”: 1910: Sarah Jane Dudley, American: (1859-1940) frontis plate to the volume: A Daughter of the Revolution by Jessie Anderson Chase: Boston: Richard G. Badger: The Gorham Press 1910: Platinum print, mounted, with Dudley’s cipher at lower right corner: 20.2 x 15.3 | 20.5 x 15.7 cm: Besides her interest in amateur photography, Whitensville, Massachusetts native Jane Dudley, a graduate of Wheaton Female Seminary, was the organizer of the Samaritan Association of Whitinsville. This vintage example of a genre study showing children dressed in 18th century clothing while dressing their doll in an attic was done in the very popular style at the beginning of the 20th Century known as “Colonial Revival”, which took advantage of America’s love of its’ colonial past. From: PhotoSeed Archive

From: A Dissertation on the Canon and Feudal Law-1765

Liberty cannot be preserved without a general knowledge among the people, who have a right, from the frame of their nature, to knowledge, as their great Creator, who does nothing in vain, has given them understandings, and a desire to know; but besides this, they have a right, an indisputable, unalienable, indefeasible, divine right to that most dreaded and envied kind of knowledge, I mean, of the characters and conduct of their rulers.

–John Adams