“Sunlight is said to be the best of disinfectants” —Louis Brandeis, U.S. Supreme Court Justice, 1913

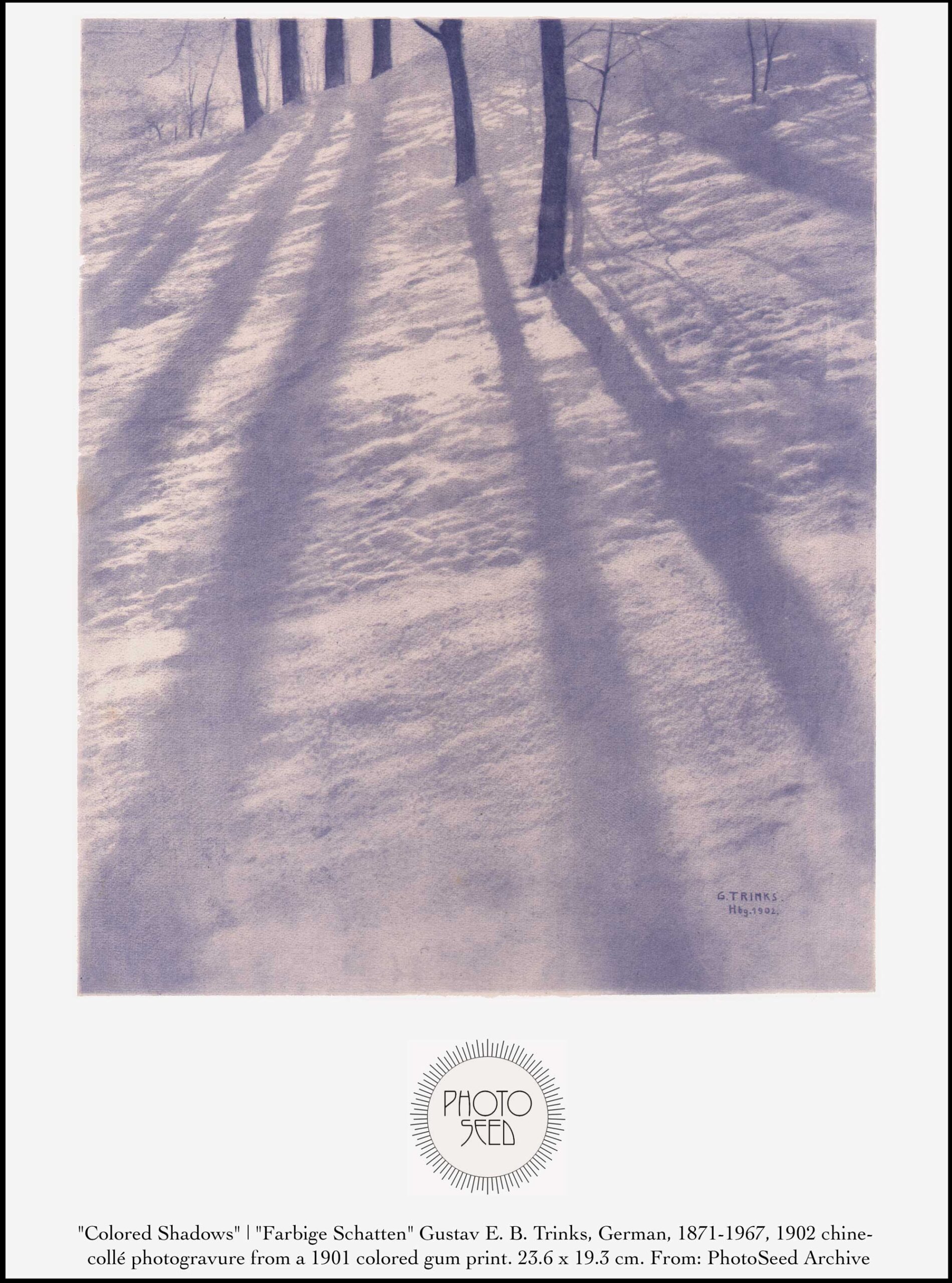

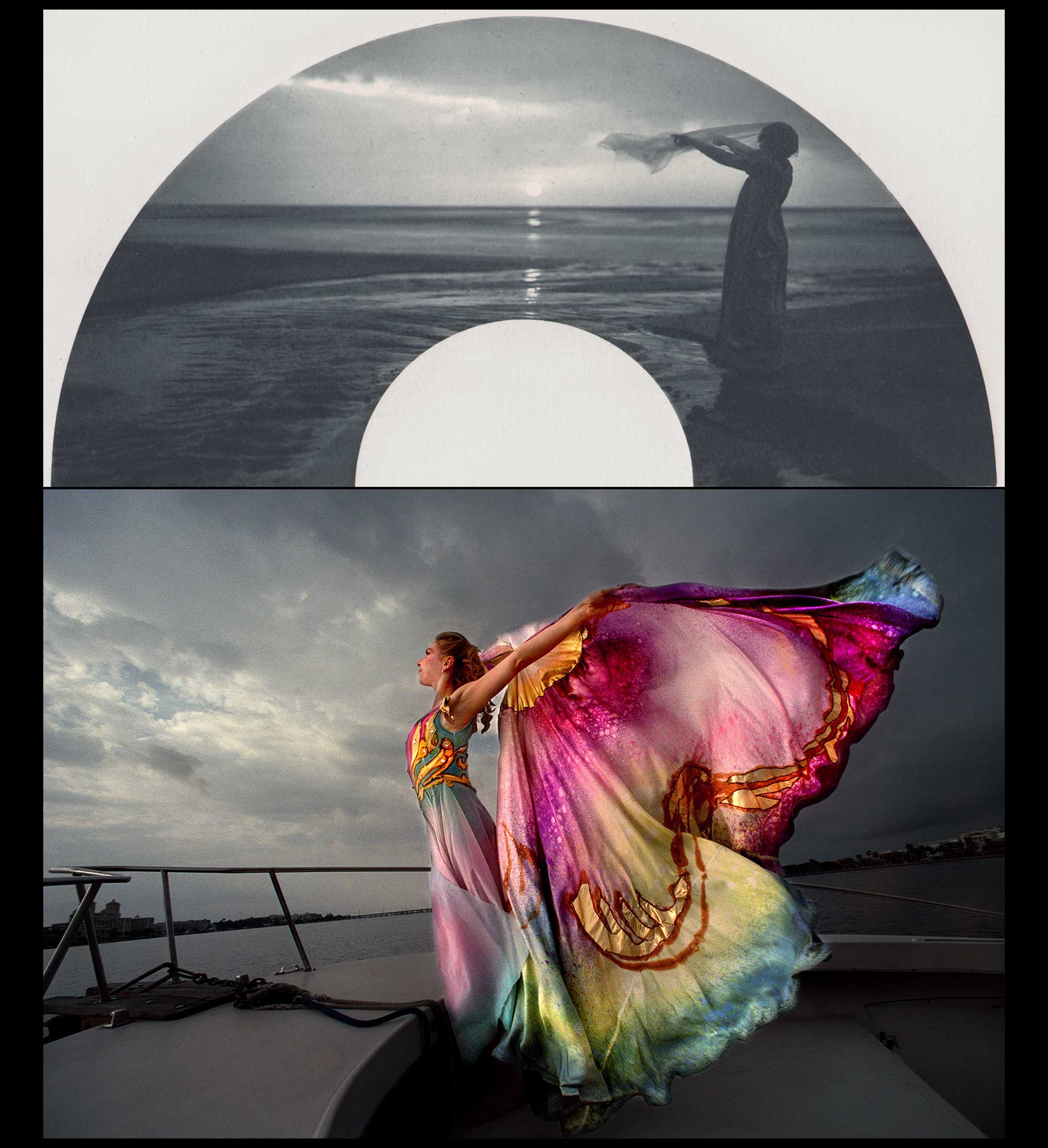

Top: The Sun takes center stage: Detail: “La Perle Doucement S’ Éteint et la Danse S’ Arrête | The Pearl Slowly Fades Away and the Dance Stops” Pierre Dubreuil, Belgian (1872-1944) Photogravure: Chine-collé: published in Die Kunst in der Photographie: 1903: Lieferung 1 | First Issue-16.5 x 23.0 | 26.6 x 34.8 cm. A critic on this photograph from 1901:”Now the light gradually dies and with it the dance fades away, for dance is a child of the light. They have whirled around for the last time, their movements become more subdued and tired, and now they stand still. They hold hands and lean back, as if in delicious relaxation. They look long and deeply into each other’s eyes once more while the sun sets.” Bottom: The Sun clouded over: Believed to be the original source material compositionally for Dubreuil’s photograph above: Detail: “Strassenklatsch | Street Gossip” Alfred Stieglitz, American (1864-1946) Photogravure published in Die Kunst in der Photographie: 1899: Lieferung 5 | Fifth Issue-12.2 x 21.0 | 24.9 x 33.7 cm. In her book: Stieglitz-A Beginning Light, author Katherine Hoffman comments about this photograph: “Another well-known Katwyk image depicts the prow of a boat at anchor, its boom, lower sail, and rigging forming varied triangles. The prow of the boat points toward two women talking nearby at the water’s edge. Entitled, Gossip, Katwyk, the photograph focuses on narrative and formal elements. The women stand firm, their hands on their hips, forming small triangles that balance the ship’s forms and one of the women looks toward the ship. The strong horizontal elements of the beach, water, and sky, serve as a well-integrated backdrop for the women and ship. The small lantern on the boat seems to light the image symbolically.” Both from PhotoSeed Archive

This Brandeis quote is widely cited today as referring to the benefits of openness and transparency-especially as it pertains to keeping democracy vital and thriving.

So what does this have to do with a blog dedicated to preserving, promoting and riffing on the history of artistic photography?

Well, unfortunately, not much at all. That is, if only we were to think of photography as a truthful medium- something that accurately records for posterity what is placed before it or “seen” by the camera. That evidence would be from an impartial machine, and honesty might prevail. But as we traverse the second decade of the 21st Century, technology is taking a brutal hammer to what our once (believing) eyes took for fact. The sunlight of truthfulness has gotten a bit dim of late, yielding, inevitably, to “progress”. Of course, arguments could be made that photography has lied ever since the invention of the medium. Longtime readers of this blog might remember how I wrote about unscrupulous “photographers” operating in the mid 19th century who would trick people into believing the camera itself could mesmerize them. Today, as of October 2024, when I first spotted it, the updated version of mesmerization is now done courtesy of AI. (artificial intelligence) Here’s an Orwellian example of that in what I will call the Ebay photographic caption from Hell that should help put things in perspective:

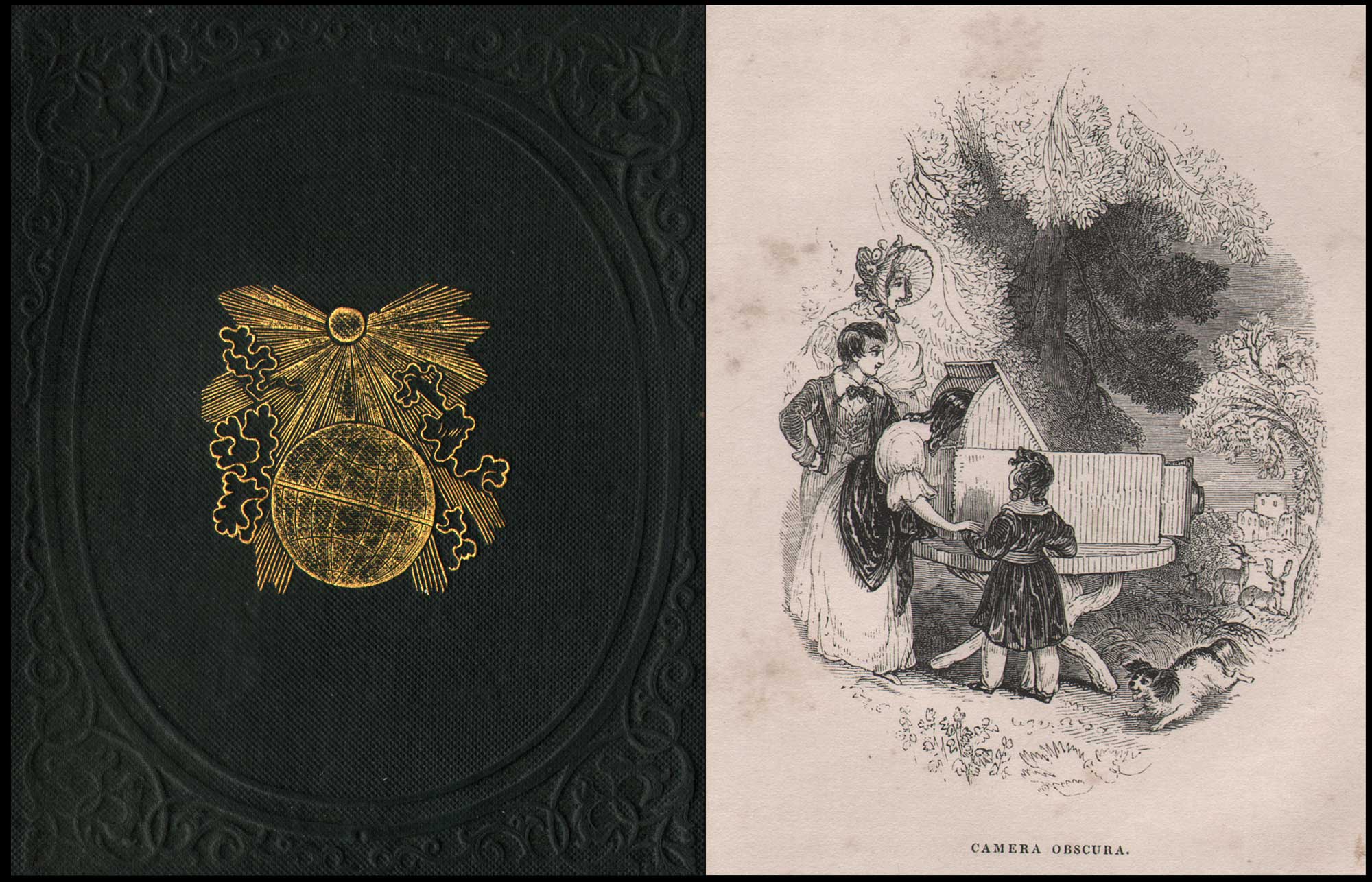

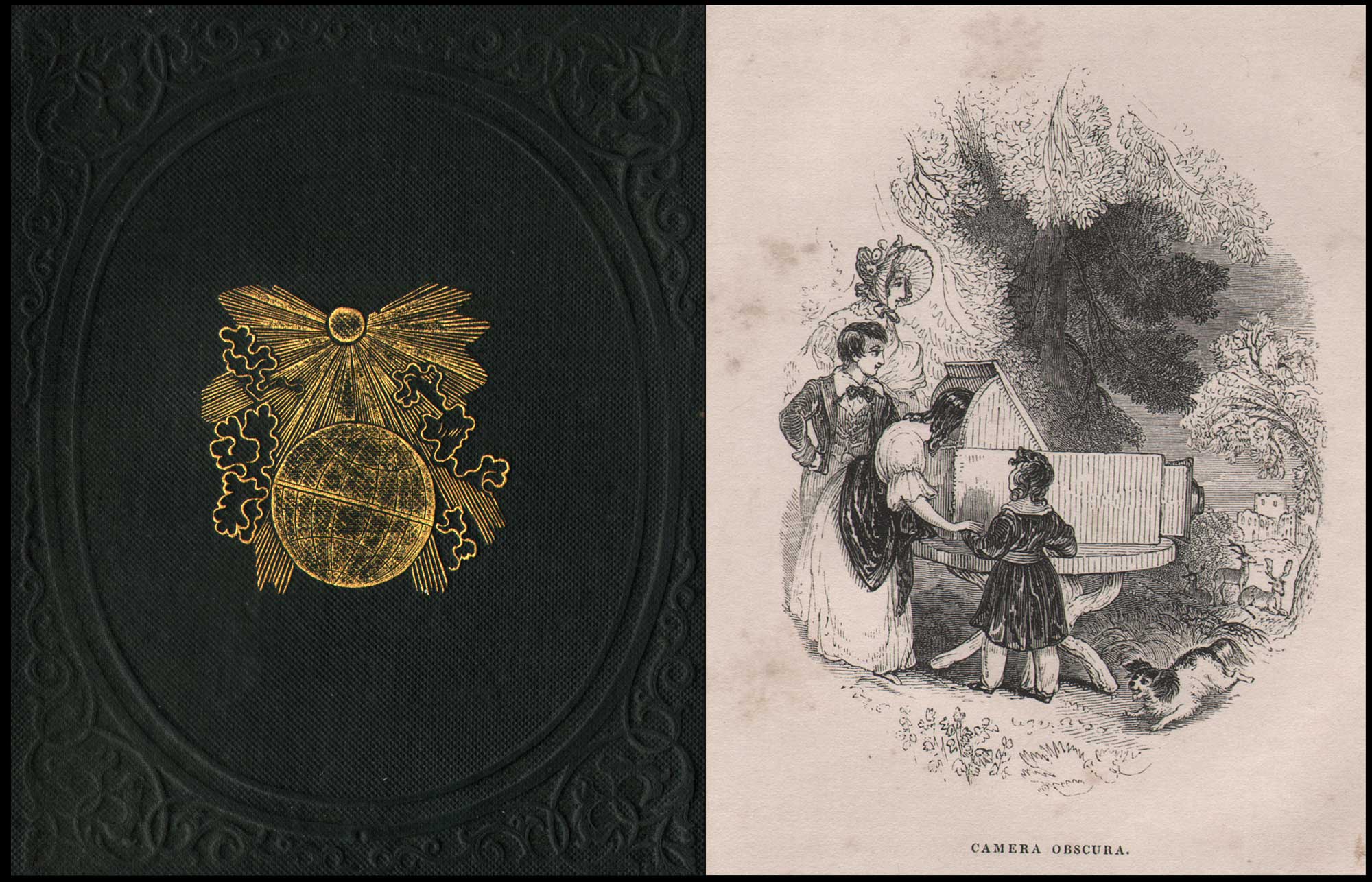

Left: The Rays of the Sun cover the Earth: Before Photography, the public consciousness was getting more familiar with scientific thought in the press. Detail: Gilt decoration of the Sun and Earth: volume cover: “Light: Its Properties And Effects” London: The Religious Tract Society, 1838. 18mo: 5.5” x 4.25”. Illustrated with 40 steel engravings, an 1839 reviewer wrote of this little book: It is written in a simple style, but introduces the reader to all the arcana of the science which it touches. The anecdotes of singular illusions and the explanations of them enliven it, and serve to impress the general principles and laws of light more distinctly upon the mind. And, as may be believed from the fact of its issuing from the Tract Society, it fails not to point the learner “To look thro’ nature up to nature’s God.” Right: “Camera Obscura”, unknown artist: full-page steel engraving from “Light”- Chapter XI: Lenses-The telescope-The microscope-Various Optical Instruments: 13.5 x 9.8 cm. A family peers into a very large Camera Obscura placed on a table. Cameras such as this would eventually be retrofitted to accommodate chemically altered sheets of writing paper placed within-part of the process of making Photogenic Drawings and early Calotypes. From: PhotoSeed Archive

“This vintage photograph captures a momentous occasion in Yellowstone National Park in 1892. The image depicts a family who was taken by a tripod rigged. The photograph is in sepia tone and has a size of H18 3/10 cm x W21 5/10 cm. The image is produced using a photographic technique and features the Richardsons family. This collectible item is perfect for photography enthusiasts and collectors alike.“

So far, kinda good, other than the “tripod rigged” mention and the fact no one really speaks of common snapshots of Victorians chilling in nature as a “momentous occasion”. It would soon become apparent that our new friend AI was hard at work to really sell this photo. The caption continues:

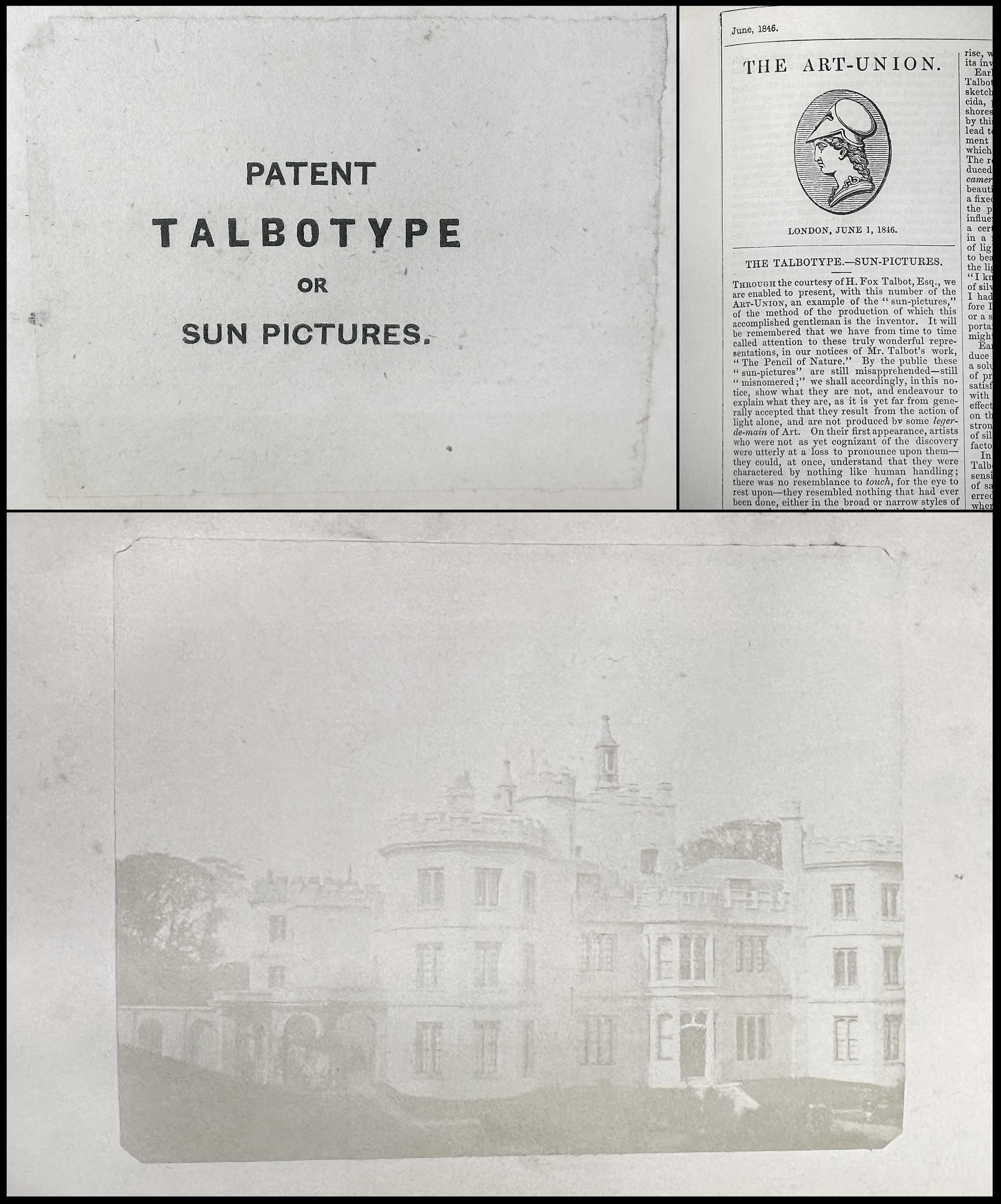

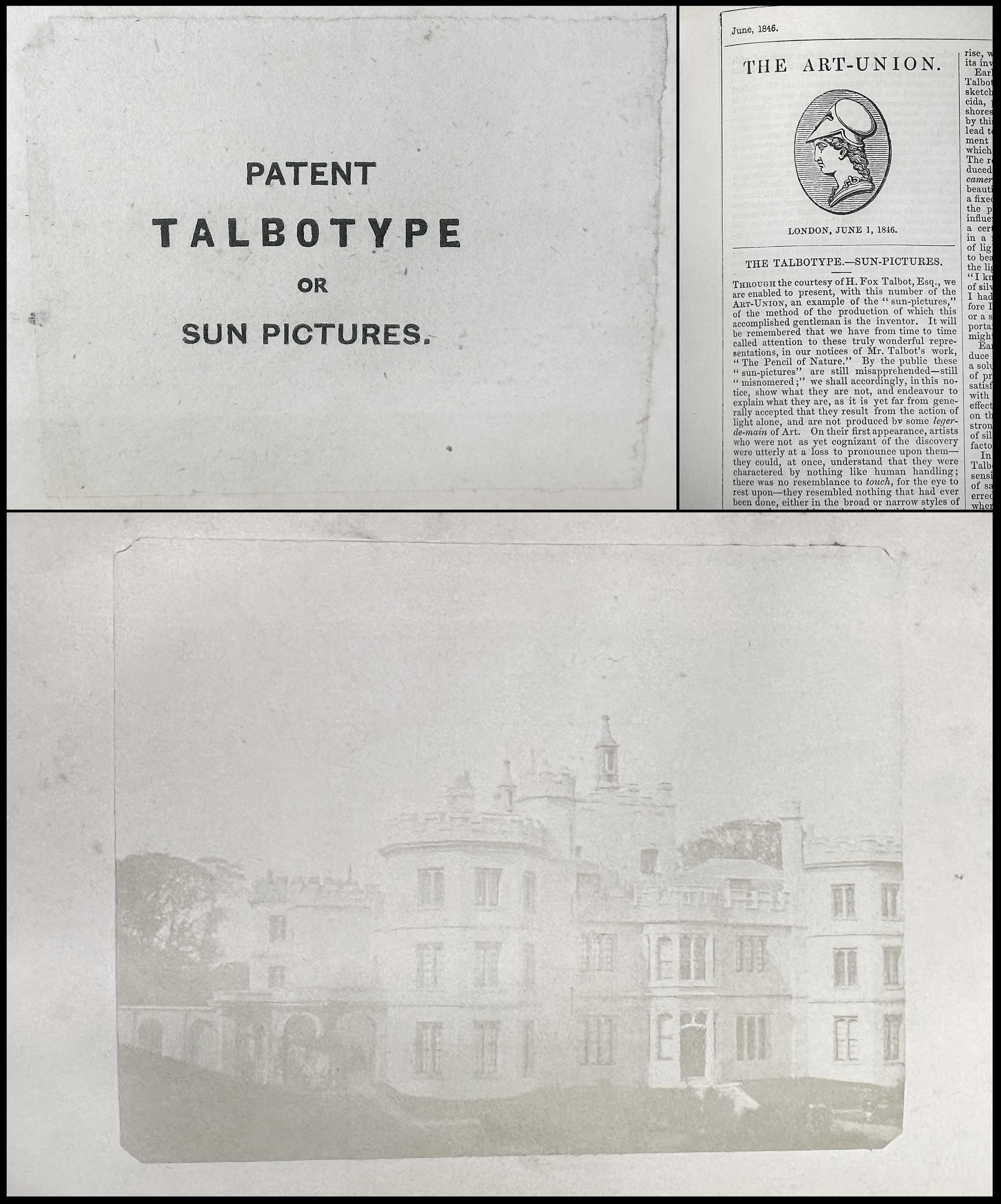

Top left: First mass market publication of a “Sun Picture”: pasted paper label: PATENT TALBOTYPE or SUN PICTURES. 5.8 x 7.1 cm. Affixed to verso of leaf: 22.6 x 28.6 cm. 1846. Contained in “Art-Union Journal”. Top right: The editors of the publication were keen to go into detail on how Fox Talbot’s “Sun Pictures” (calotypes) were made, refuting the notion they were done by some sleight of hand, and even gave a detailed account of how these photographs were made. Bottom: “Mount Edgcumbe House, Devon” William Henry Fox Talbot, English, (1800-1877) salted paper print inserted in June 1, 1846 issue of the Art-Union Journal, London. 15.7 x 20.0 cm pasted to leaf 22.6 x 28.6 cm. Extremely rare but heavily faded, with the main facade of the home clearly identifiable, this is one of a believed 6000 original Talbotypes published in the Art Union. Various other views were also supplied by Talbot for the publication, a commission unfortunately compromised by the fact all of the calotypes were believed to be insufficiently fixed and washed by Nicolaas Henneman’s overworked Reading printing establishment. From: PhotoSeed Archive

“The Richardson Family was off on an expedition and there were no cell phones and there was no one out there and there were no Rangers and there were no Rescuers and nobody could save them if they where to call out and that’s what it was like in those days and they put their lives in front of nature and they didn’t think ahead of time to prepare if any natural occurrences would come along with bears and mountain lions.”

So yeah. What could possibly go wrong in our brave new world? I say bring on the sunlight. And lots of it. Call out the fakes. Push back. We here at PhotoSeed are big fans of transparency. Who wants to collect a “vintage” photograph with that kind of back story or an obvious fake of great, great grandma or grandad run through an AI filter? Well someone of course, and that’s cool too- whatever floats your boat and all that. But I digress.

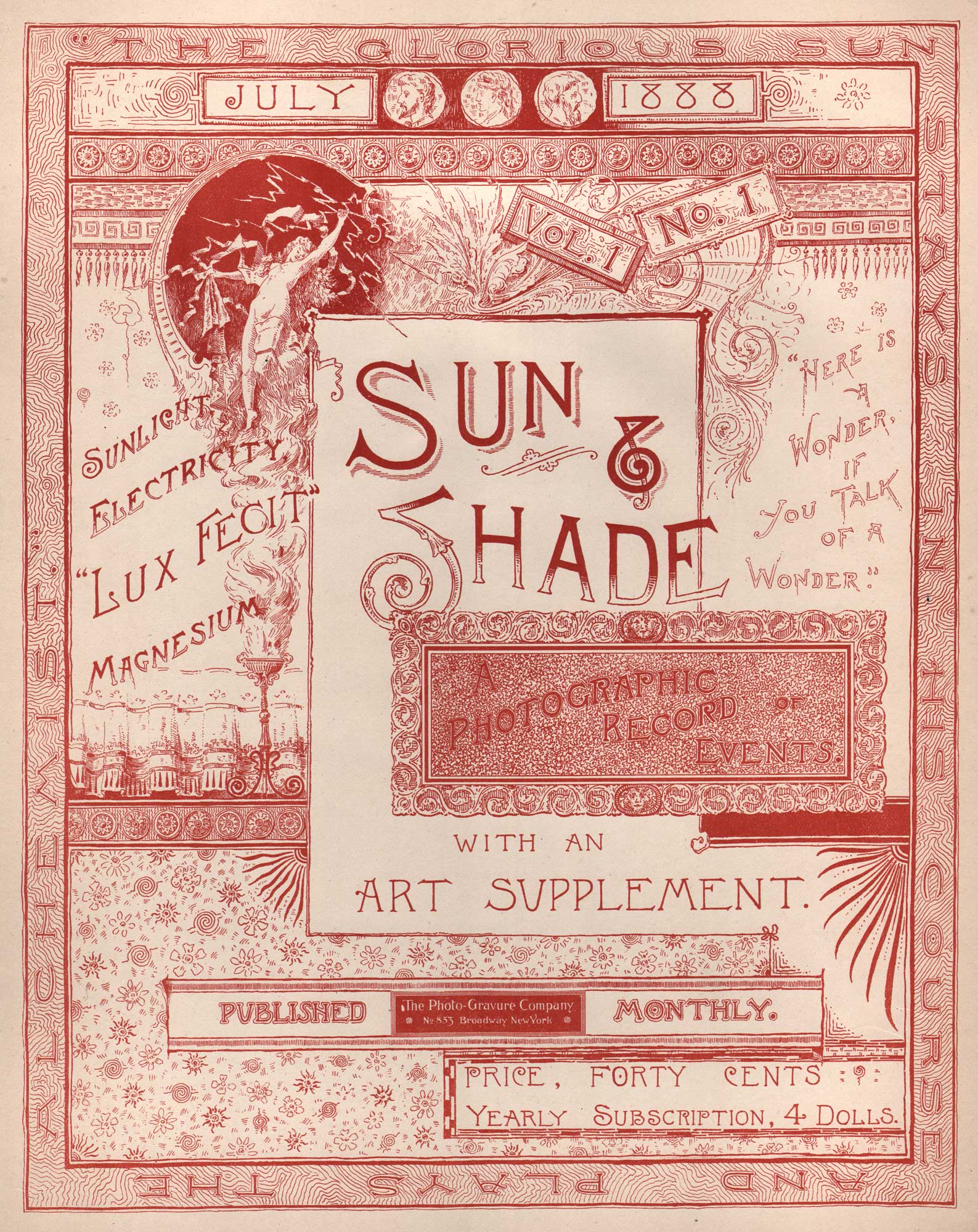

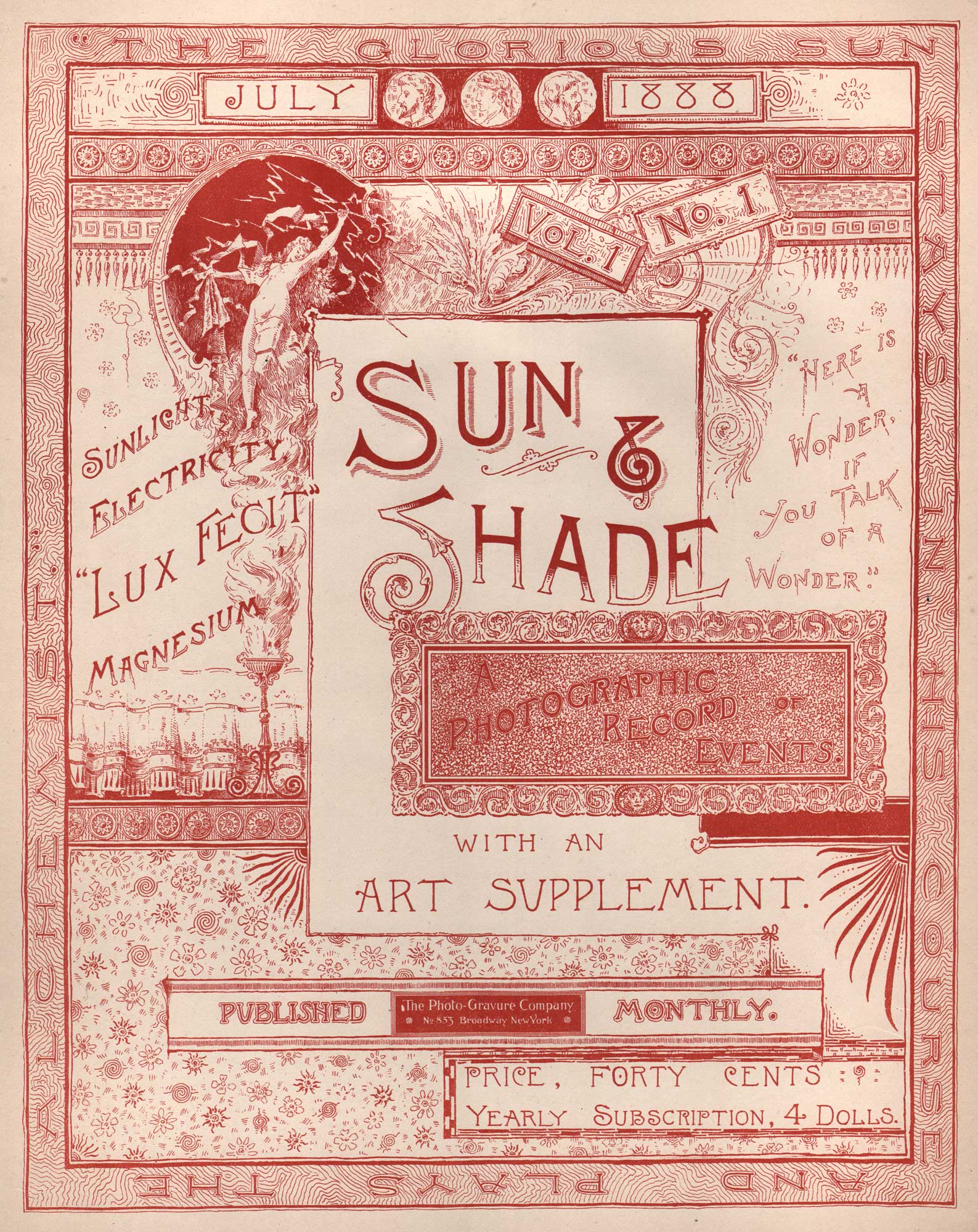

“The Glorious Sun: Stays In His Course And Plays The Alchemist” : “Here is a Wonder, if You Talk of a Wonder” were phrases incorporated into the elaborately engraved title page to the very first issue of “Sun & Shade-A Photographic Record of Events”: July, 1888. Unknown American artist, possibly George Wharton Edwards, (1859-1950) credited with cover design for issues beginning around 1890. 30.5 x 24.1 | 35.2 x 27.6 cm. Published by the The Photo-Gravure Company of New York by Ernest Edwards, the publication, according to the volume “Imagining Paradise”, “grew from less than fifty subscribers to a monthly edition of four thousand copies” in its first year. “With emphasis on quality rather than quantity, the magazine transformed itself from its original concept of a “Photographic Record of Events” to an “Artistic Periodical”, and would feature many fine photogravure plates, mainly from photographs but also artwork. From: PhotoSeed Archive

Sunlight- as a kind of invisible chemical medium- was everything to the existence of early photography. Similar to AI today in that enabling it is just a few clicks on a computer keyboard, and may remain a mystery to unsuspecting viewers, people did not understand what a photograph was or how they were made in the earliest version of the medium. Sunlight provided that answer, or at least a reasoning. The ever-present Sun overhead provided the means for these early efforts. In the 1830s, the Englishman William Henry Fox Talbot, a botanist among other passions, experimented by recording the shapes of things like leaves and lace, contact printing these on sheets of chemically altered writing paper. The results were known as “photogenic drawings”, or drawings produced by light. It’s no wonder promotion of early photography involved the iconography of our friend the Sun.

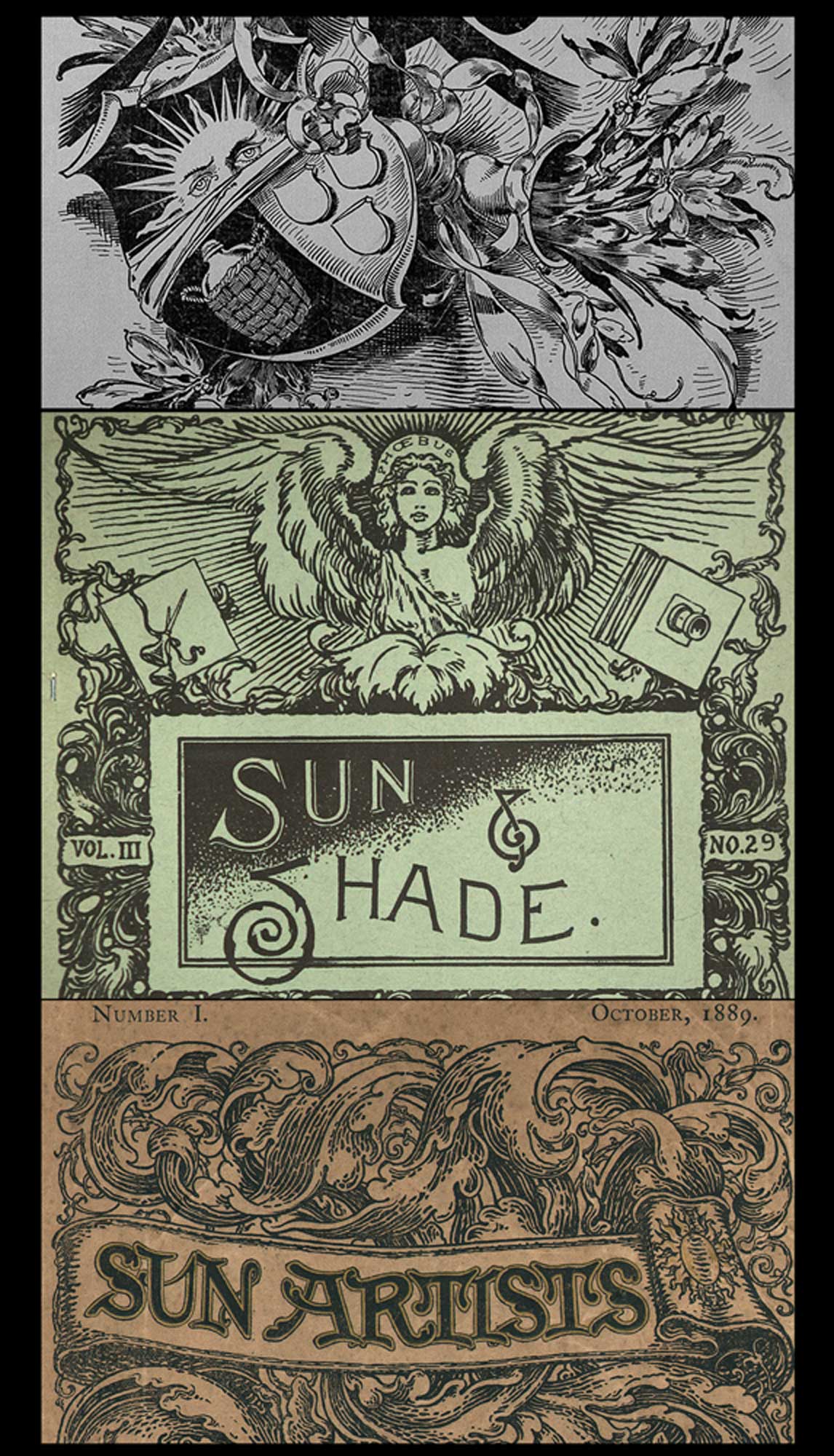

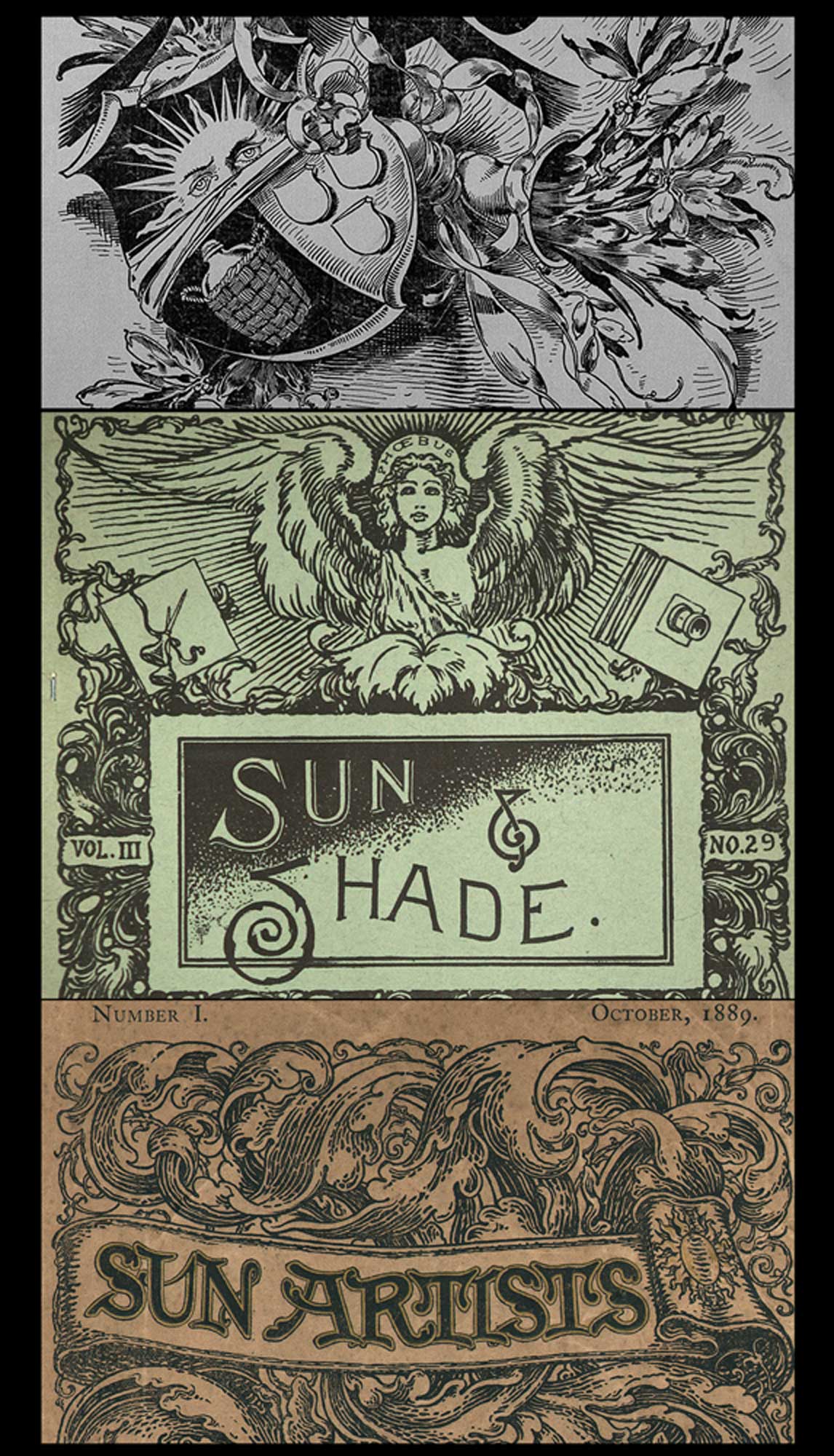

Top: The Eyes of the Sun: Sun iconography was incorporated like this example in the cover design to the important Austrian portfolio Amateur-Kunst, (Amateur Art) published in late 1891 by the Vienna publishing house Gesellschaft für Vervielfältigende Kunst. Detail: gray cloth over boards, three-point folder portfolio-January, 1891: Vol. III, No. 29: 49.8 x 36.6 cm. Middle: From around 1890, the Sun God Phoebus, (Apollo) one of the Olympian deities in Greek and Roman mythology, was prominently featured on covers for the publication “Sun & Shade, an Artistic Periodical” published by the N.Y. Photogravure Company from 1888-1896. Wood engraving: 35.2 x 27.6 cm. George Wharton Edwards, American (1859-1950) is responsible for the Art-Nouveau cover design, which also includes a plate camera at the upper right corner. Bottom: Detail: “Sun Artists Series Wrapper”. Multi-color wood engraving: October, 1889. 40.3 x 30.4 | 40.3 x 60.8 cm (outline of series title Sun Artists printed in gold ink) Featuring a design by English illustrator Laurence Houseman, (1865-1959) this rare example of a brown-paper wrapper for the first Number of Sun Artists originally contained four hand-pulled photogravures made from the original negatives taken by English photographer Joseph Gale, (1835-1906) as well as individual letterpress featuring an essay on this photographer’s work by George Davison. All: PhotoSeed Archive

Talbot’s Calotype process, patented in 1841 with earlier iterations being the basis for his groundbreaking positive-negative process of 1839, would be referred by him and other practitioners as “Sun Pictures”, or Talbotypes. The editors of London’s Art Union Journal exclaimed in June 1846, while presenting an original example of one of his Sun Pictures (see example above) that:

“It will be remembered that we have from time to time called attention to these truly wonderful representations, in our notices of Mr. Talbot’s work, “The Pencil of Nature.” By the public these “sun-pictures” are still misapprehended-still “misnomered;” we shall accordingly, in this notice, show what they are not, and endeavour to explain what they are, as it is yet far from generally accepted that they result from the action of light alone, and are not produced by some leger-de-main [slight of hand] of Art.”

Top left: The Painted Sun: Detail: “Study of a Nude”, 1899, Charles Fondu, Belgium: (1872-1912) collotype from Sentiment D’Art en Photographie: Vol. 1, No. 4, Planche 3: 14.8 x 19.6 | 26.0 x 36.9 cm. From the volume “The Last Decade” published in 1984 by George Eastman House, this photograph is commented on: “Fondu’s woman, combination of femme fatale and omnipotent angelic female, is profiled against the sun. Like the sunflower, the sun was a popular symbol with art photography clubs. It represented photography’s necessary light as well as the inspiration, power and renewal associated with otherworldly presence.” (p. 4) Lower left: “Family in an Explosion of Light” Emery Gondor, American (b. Hungary- 1896-1977) Linoleum cut: 1925 plate from 1923 block: 20.5 x 18.8 cm impression | 28.9 x 25.0 cm. Although better known as an artist, Emery Gondor was an accomplished photographer whose work appeared in some of the largest European newspapers (principally German) from the mid 1920’s into the 1930’s. He escaped the Nazi regime, emigrating to America in 1935. This plate from his unpublished folio: “Sehnsucht nach Licht” (Yearning for Light) : “8 original Linoleum cuts by Emerich Göndör”. Right: The Sun in etched form: Detail: “Folder: Die Kunst in der Photographie” Hermann Hirzel, born Switzerland, (1864-1939) 36.0 x 26.5 cm Originally etched in 1896, Hirzel’s cover design showing a Faun playing his flute among a landscape of trees and the rising Sun was used in all issues from 1897-1903. Published between 1897-1908 by Franz Goerke in Germany, Die Kunst in der Photographie is one of the most important journals of photography ever published showcasing artistic photography from around the world. All: PhotoSeed Archive

The article continues and even gives the chemical formula for making sensitized Calotype paper that could be exposed in a camera obscura. (1.) Terminology developed rapidly from here. To differentiate in the public discourse from a painting or drawing made by hand, these new “photographs” would hence be referred to as being “From Nature.” The one constant of this wondrous invention was the Sun overhead. It alone was responsible for even making photography and photographs exist in the first place.

In the exhibition catalogue “The Last Decade” published in 1984 by George Eastman House, the symbolism of Sun imagery is discussed as part of an 1899 nude study by Belgian photographer Charles Fondu:“Fondu’s woman, combination of femme fatale and omnipotent angelic female, is profiled against the sun. Like the sunflower, the sun was a popular symbol with art photography clubs. It represented photography’s necessary light as well as the inspiration, power and renewal associated with otherworldly presence.” (p.4)

As a graphic device, the image of a Sun would be a great promoter for photographic achievement, and was common in print even through the first decade of the 20th Century.

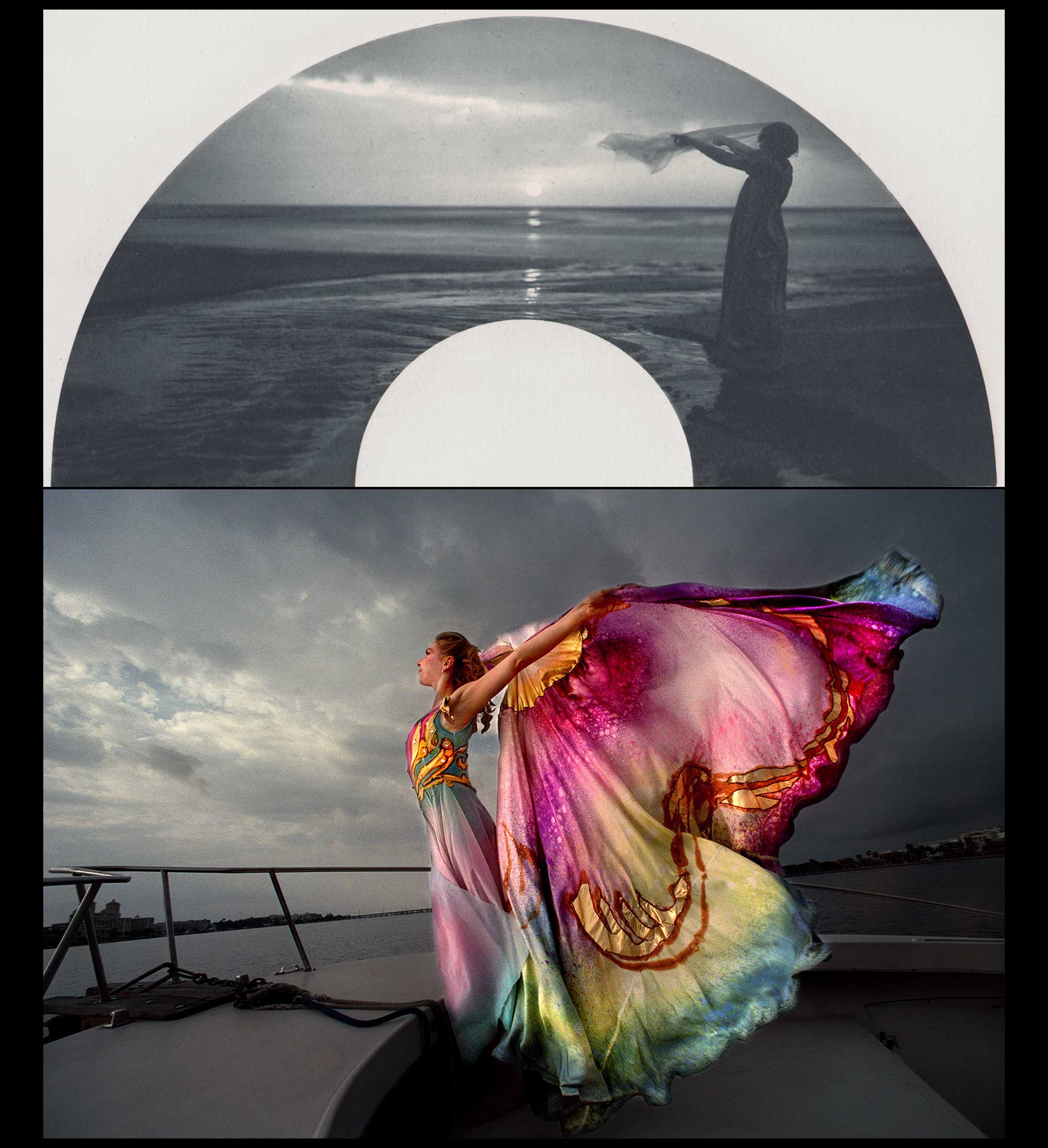

Top: The Setting Sun: “Adieux au Soleil | Farewell to the Sun” Pierre Dubreuil, Belgian (1872-1944) Photogravure: Chine-collé: published in Die Kunst in der Photographie: 1903: Lieferung 1 | First Issue-12.2 x 24.5 | 26.3 x 35.2 cm. In 1901, Fritz Loescher, in his essay On the Pictures of P. Dubreuil, comments on this photo: The farewell to the sun is wonderful in the combination of the most artistic calculation and the favor of the moment. The dark female figure, standing on the far edge of the seashore, stretching out her arms towards the departing sun, is like the embodiment of the longing for the light. And driven by the wind, the veil from the head also blows in the same direction, and the mood of this human soul is expressed in everything to the fullest.” From: PhotoSeed Archive. Bottom: My contemporary update from 2001: “Butterfly Wings”.On Lake Worth Lagoon in Palm Beach County Florida, the wings of the most beautiful butterfly is what came to mind while the wind lifted up the silk cape being held by Ballet Florida dancer Wendy Laraghy. This photo was from a series of portraits of Ballet Florida dancers in unconventional but truly believable South Florida settings and situations. The story promoted the fact the local company, based in West Palm Beach, was turning 15 years old. Photo by David Spencer/The Palm Beach Post

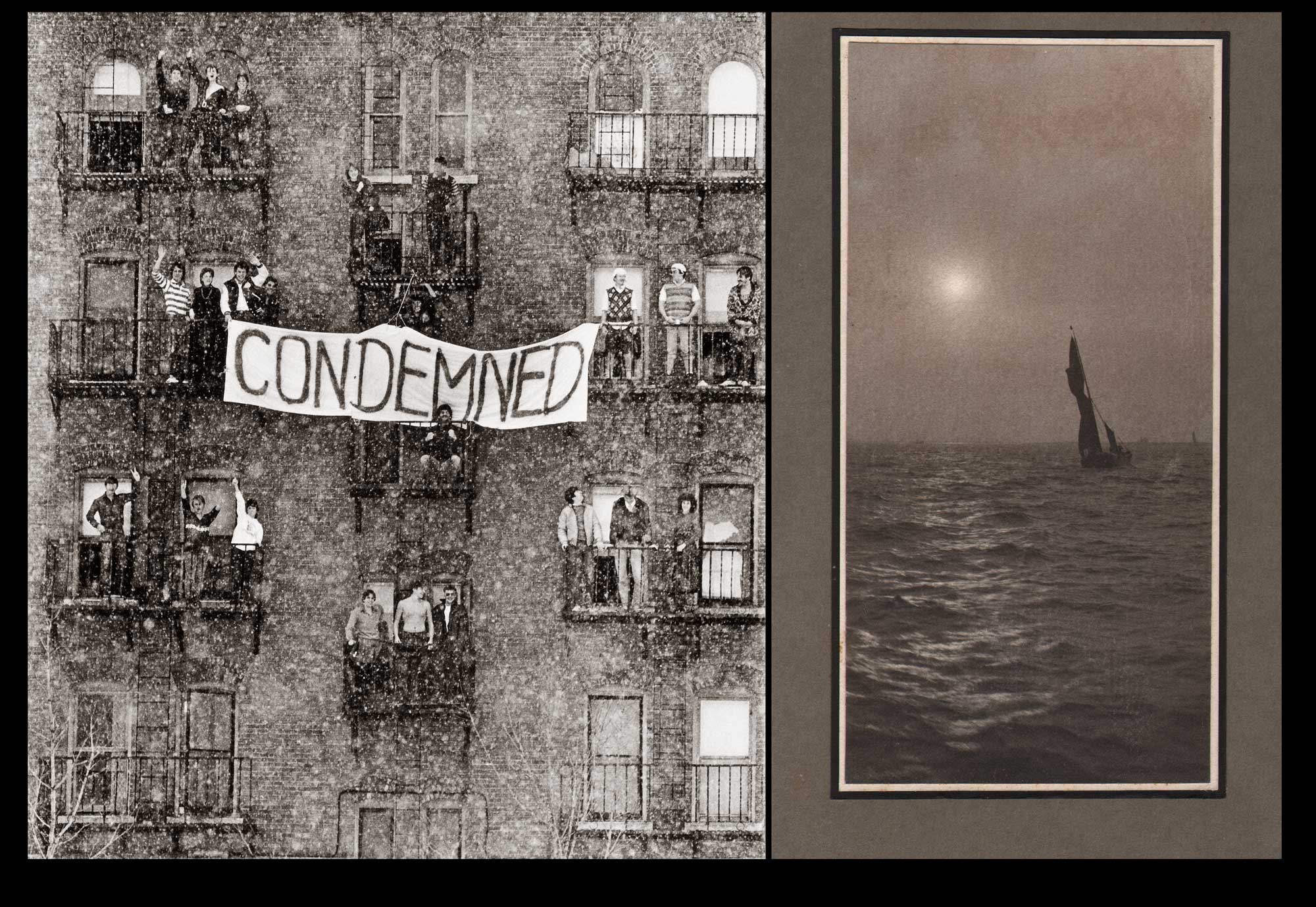

I hope you enjoy these examples of artistic photographs from nature, and have included a few of my own as modern comparisons. The contrast deliberate, my very own version of “Sun & Shade”: “Butterfly Wings” was taken in the “Sunshine State” while “Condemned” hails from the depths of an upstate New York Winter.

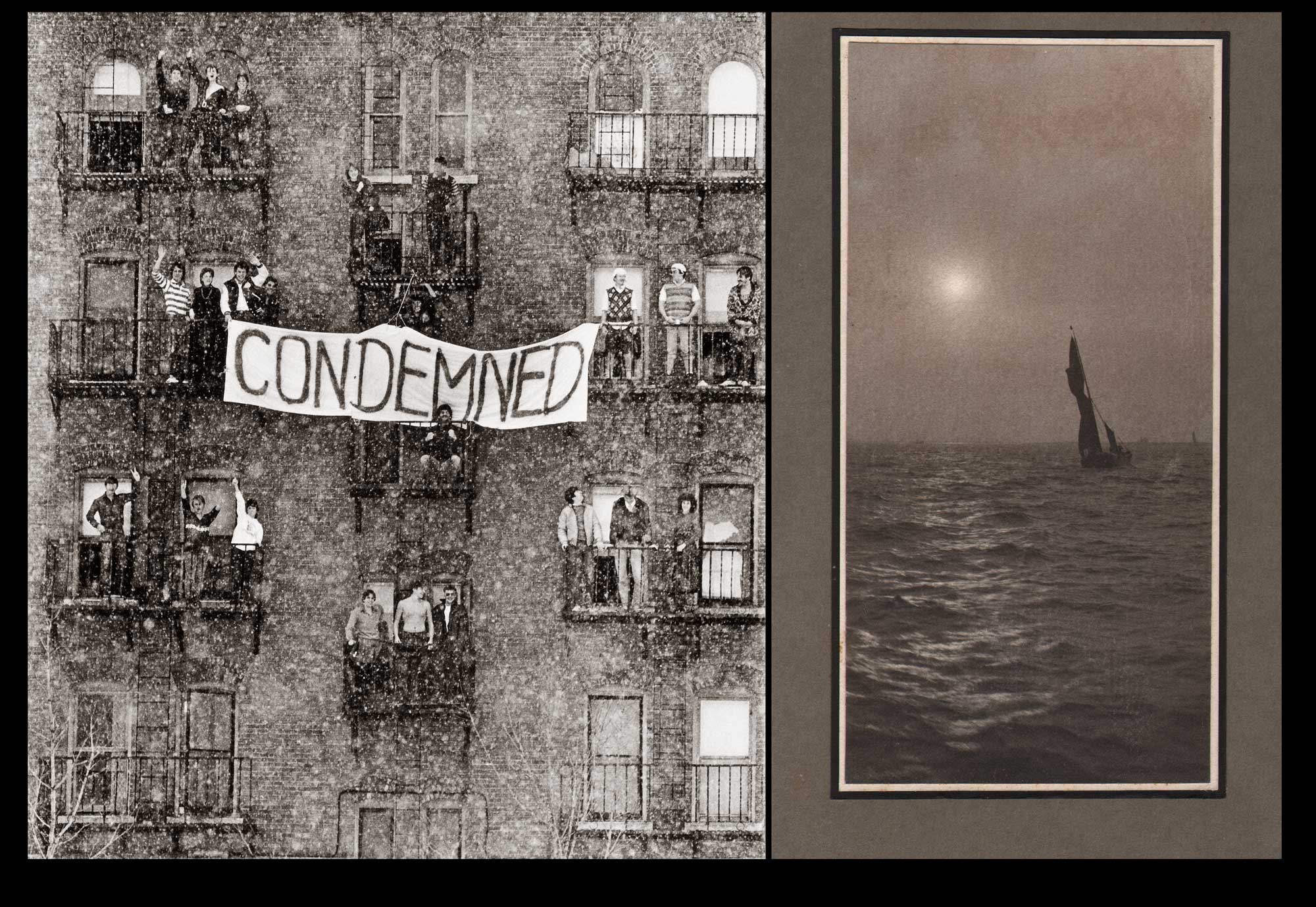

Left: The Sun: but quite hidden on a snowy day: “Condemned” :1984, from a gelatin silver print. By David Spencer for the Daily Orange. Some of the last students of Winchell Hall, on the campus of Syracuse University in New York state, hang out on exterior balconies for the last time. The first dormitory to be constructed on campus in 1900, Winchell Hall Dormitory for Women was replaced by the Schine Student Center. Right: Setting sail into the Sunset? “Off Tilbury” Ralph Rowland Rawkins, English: (1874-1951) Mounted platinum print, from the Hand Camera Postal Club Portfolio: 1904: 14.3 x 7.1 cm print | mounts: 14.6 x 7.3 | 14.9 x 7.7 | 30.4 x 25.2 cm. Rawkins, the honorary secretary for the Postal Club based in London’s Tufnell Park, took this photograph of a sailboat silhouetted against a hazy, sunny sky in September, 1904. From: PhotoSeed Archive

Even in our current digital age, the Sun, giver of all life, continues to make photography possible by giving complex machines the illumination necessary to record our everyday existences and its many hues, shapes and wonders. But it’s a layered argument, the Sun being symbolic as well. Take my last photograph in this post. It’s the winter of 1983 (2.) and my assignment for The Daily Orange student newspaper was to photograph the final residents of the old Winchell Hall dormitory on campus, soon to face the wrecking ball. A snowstorm, as was common on a Syracuse winter day back then, was in full force. Stage directing the scene from across the street while somehow convincing the students to all climb out onto their respective room balconies was actually the easy part. What I didn’t anticipate were all the smiles that erupted, the finger pointing and general merriment the act of taking the photograph brought about. Sure, the old building was coming down to be replaced by a bright new shiny object, but these students had been forever immortalized in a photograph. And a truthful one at that: an unmanipulated moment where their futures were truly bright, and one where future dreams would surely include many bright tomorrows.

- Excerpt: The Talbotype. ⎯ Sun Pictures. The Art Union Journal, June 1, 1846 pp. 143-44.

-

I may have actually photographed this scene in mid January, 1984. From the SU archives: “While in the process of being demolished to make room for the building of Schine Student Center, a fire, possibly arson, swept through Winchell in early February 1984 and hastened the venerable structure’s end. in early 1984.” Read more about the history of Winchell Hall.