“And I never saw that love did any harm anywhere or was complained about O my brothers when you understood it:

For that’s about all life comes to anyhow—comes to the love we can put into it:

I just give you what I’ve got, dear comrades.” -Horace Traubel

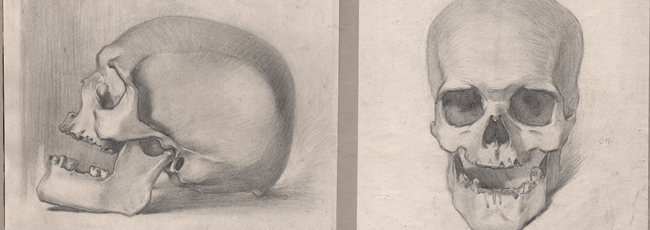

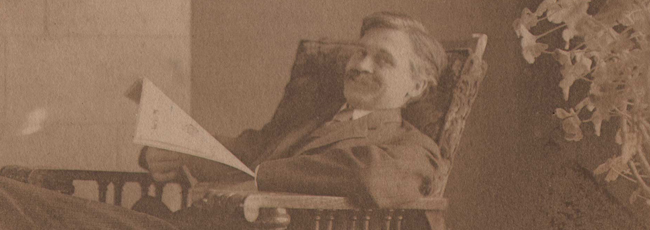

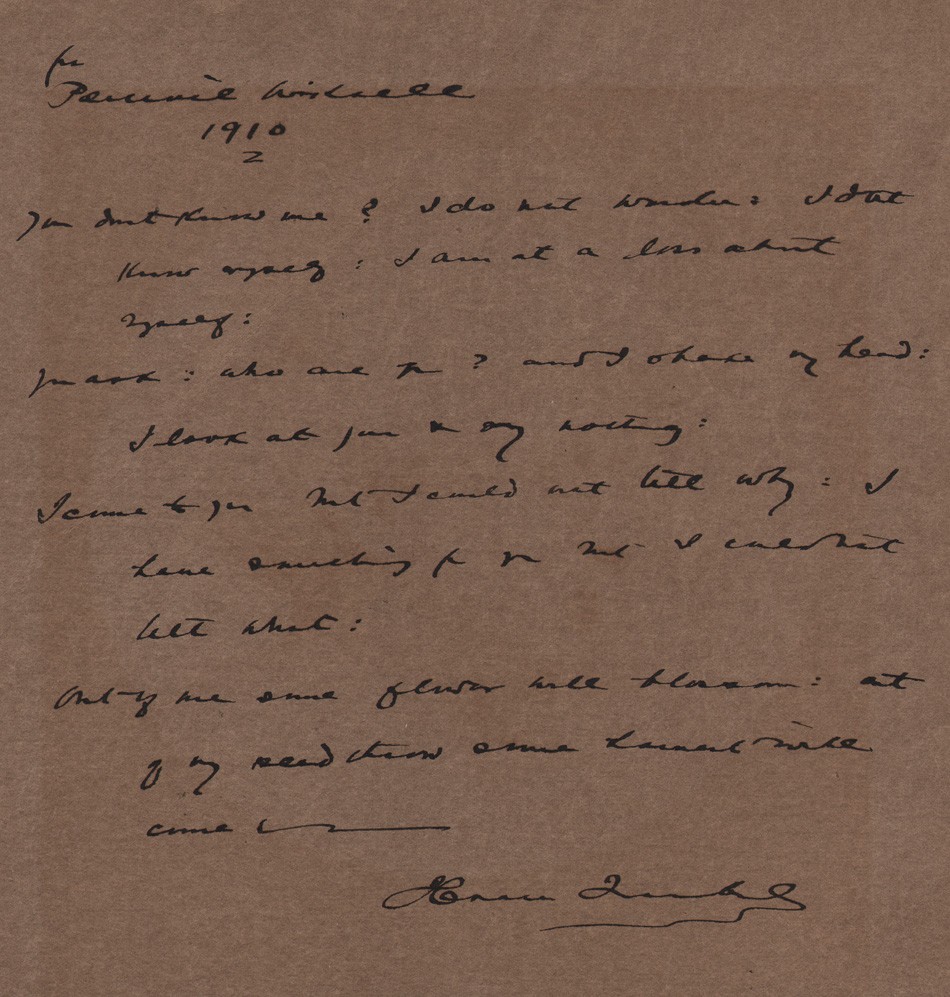

“Horace Traubel: Roundel Portrait” : Allen Drew Cook, American (1871-1923): 1910: mounted platinum print contained within folder: 17.4” roundel on paper 23.7 x 19.6 cm; supports: 24.8 x 20.6 | 28.4 x 23.9 cm. Folder: 29.4 x 48.8 cm. This print dedicated to Gustave Percival Wiksell (1863-1940): “Wiksell” in upper left corner of print recto; signed “Horace Traubel 1910” at lower right. Best remembered as the literary executor and biographer extraordinaire of America’s first national poet Walt Whitman, this uncommon profile portrait features the American editor and poet Horace Logo Traubel. (1858-1919) Traubel, a magazine publisher and committed socialist who held Whitman’s hand on his deathbed and earlier compiled nearly two million words over the the last four years in daily conversations with the poet, later transcribed and ultimately published what would become the nine volume opus: “With Walt Whitman in Camden”. From: PhotoSeed Archive

In this 200th anniversary year of American poet Walt Whitman’s birth, articles and exhibitions abound, celebrating the continuing relevance of America’s “Bard of Democracy”. But who was largely responsible for initially preserving, and thus memorializing for a larger audience this most important literary voice? A gentleman by the name of Horace Traubel. (1858-1919)

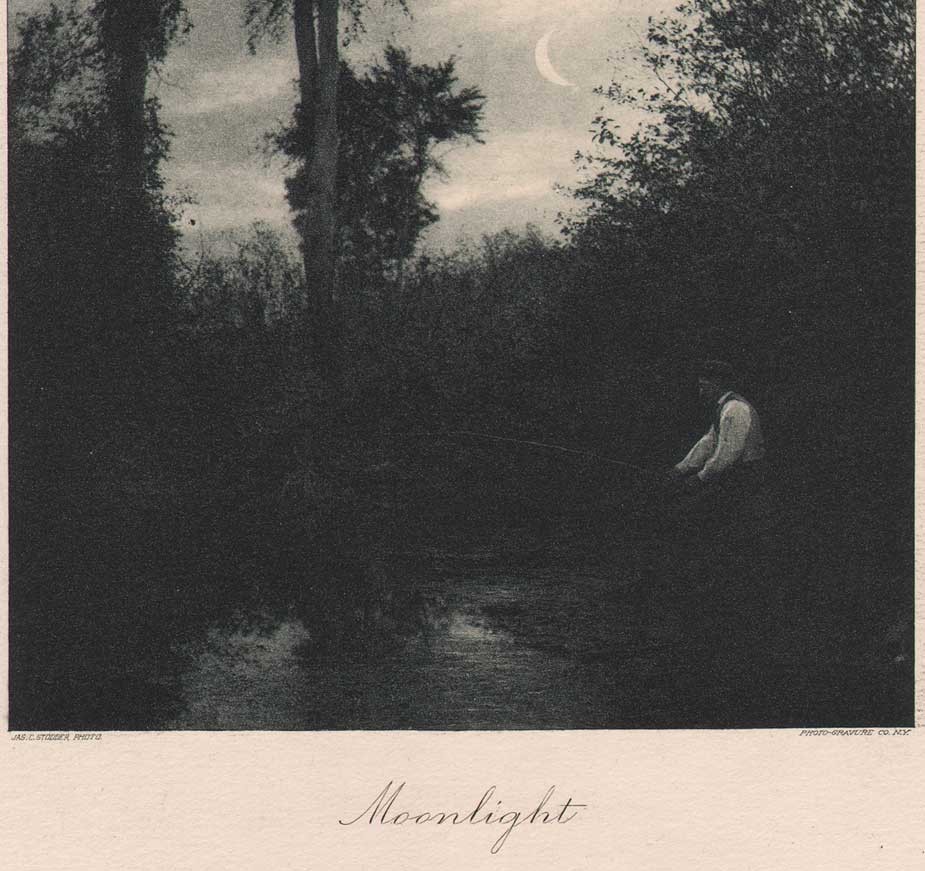

Three years ago I had the good fortune of purchasing a heraldic roundel portrait of Traubel, the one featured above taken by a fellow Philadelphian, pictorialist photographer Allen Drew Cook. (1871-1923)

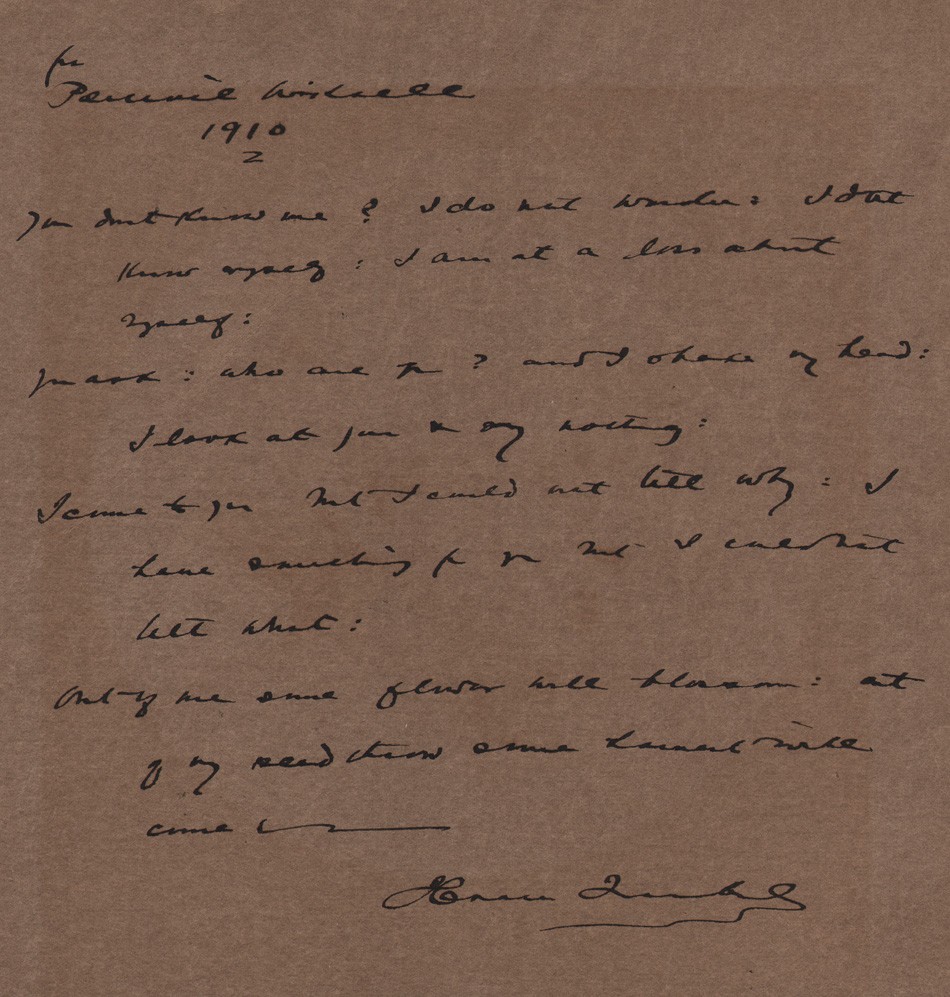

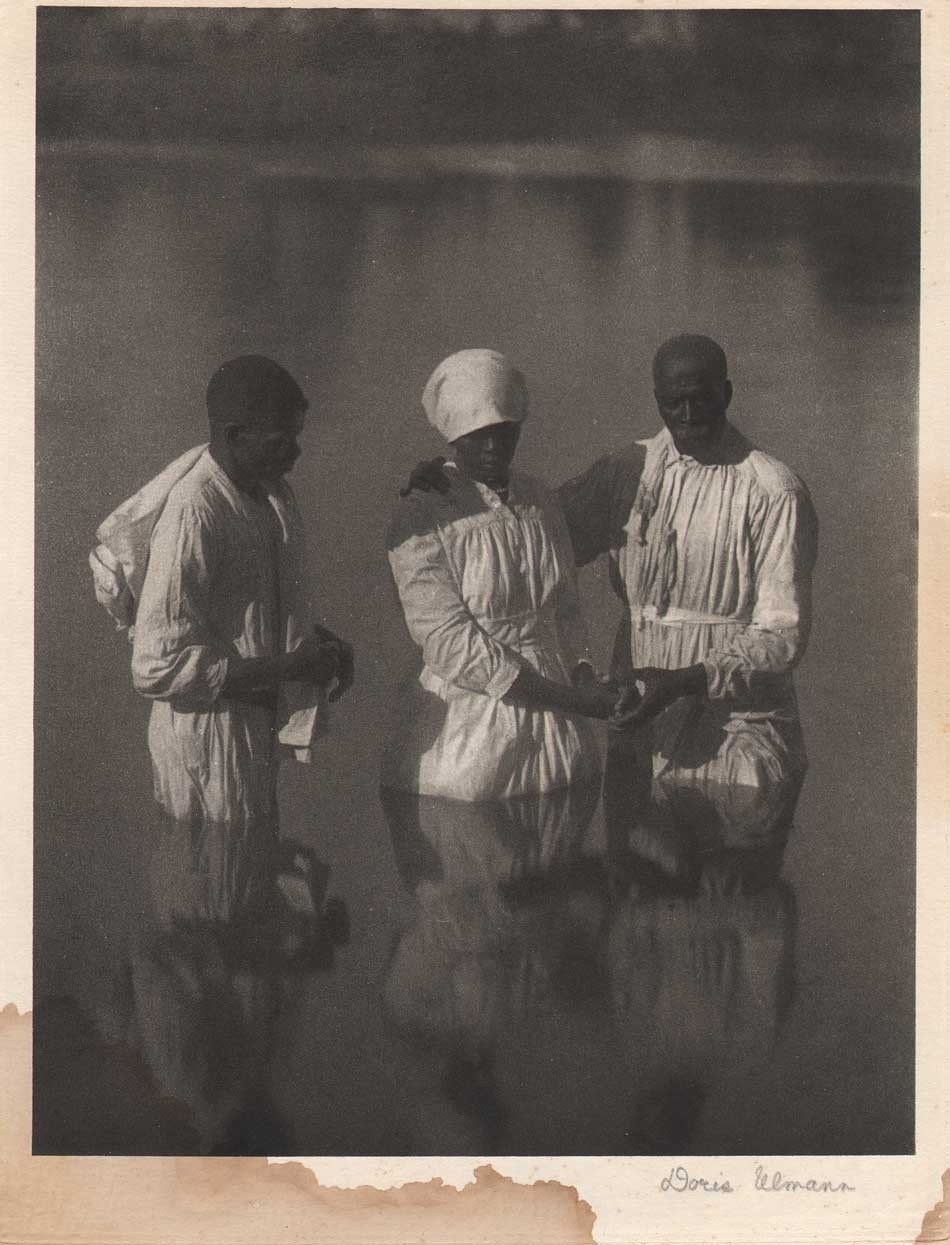

Lines addressed to Gustave Percival Wiksell (1863-1940) from the Horace Traubel poem “I Just Give You What I’ve Got” (from “Optimos”- 1910) in hand of author on inside front cover to folder containing photograph “Horace Traubel: Roundel Portrait”. Wiksell was a Boston dentist who served as president of the Walt Whitman Fellowship from 1903-1919. “You don’t know me? I do not wonder: I dont know myself: I am at a loss about myself: You ask: who are you? and I shake my head : I look at you and say nothing: I come to you but I could not tell why: I have something for you but I could not tell what: Out of me some flower will blossom out of my seedthrow some harvest will come. – Horace Traubel”. Writing in the Mickle Street Review No. 16, (2004) U.S. scholar Michael Robertson’s article “The Gospel According To Horace: Horace Traubel And The Walt Whitman Fellowship” outlines Traubel’s and Wiksell’s relationship: “However, Traubel’s letters to Wiksell move beyond comradeship into physically explicit expressions of desire. “I dream of . . . the little bed in your paradise and the two arms of a brother that accept me in their divine partnership,”(114) Traubel wrote shortly before traveling to Boston. After his visit, he wrote longingly, “I sit here and write you a letter. It is not a pen that is writing. It is the lips that you have kissed. It is the body that you have traversed over and over with your consecrating palm. Do you not feel that body? Do you not feel the return?”(115) These and other letters leave little doubt that the two men had a sexual love affair, an affair that seems to have been remarkably guilt-free. Wiksell’s letters to Traubel refer to his own wife and child and mix heavy-breathing passion with cheery greetings to “Annie and Gertrude,”(116) Traubel’s wife and daughter.”(114-“I dream of”: Traubel to Wiksell, 3 Jan. 1904, WC.; 115-“I sit here”: Traubel to Wiksell, 12 May 1904, WC.; 116-“Annie and Gertrude”: Wiksell to Traubel, 30 Dec. 1901, TC.) From: PhotoSeed Archive

Best remembered as the literary executor and biographer extraordinaire of Walt Whitman, Horace Traubel was also a magazine publisher and committed socialist who held the poet’s hand on his deathbed and compiled nearly two million words over the last four years in daily conversations with him, later transcribing and publishing in his lifetime the first three volumes of what would become his nine volume opus: With Walt Whitman in Camden. (completed 1996)

Unlike Whitman, whom The Guardian newspaper notes in an article published this year “was also the 19th century’s most photographed American writer”, (1.) there are only a smattering of photographs featuring Traubel-most being credited to Cook. By and large, Horace Traubel is a figure in American letters most people have never heard of.

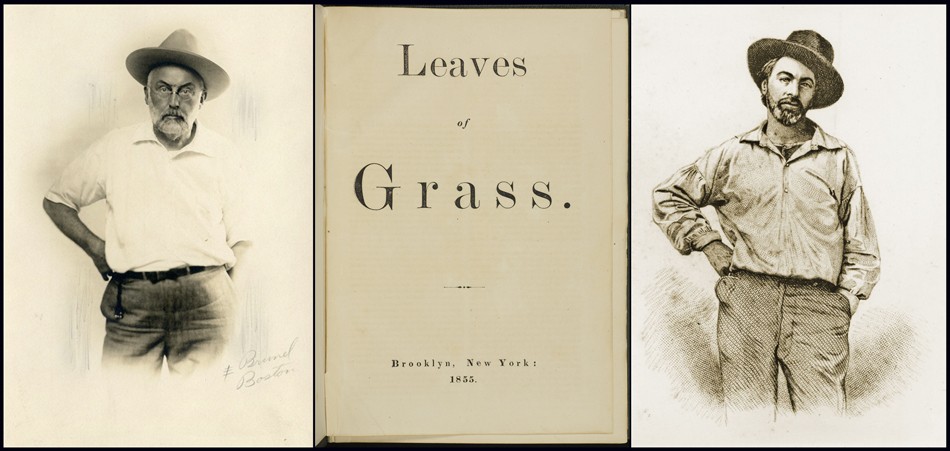

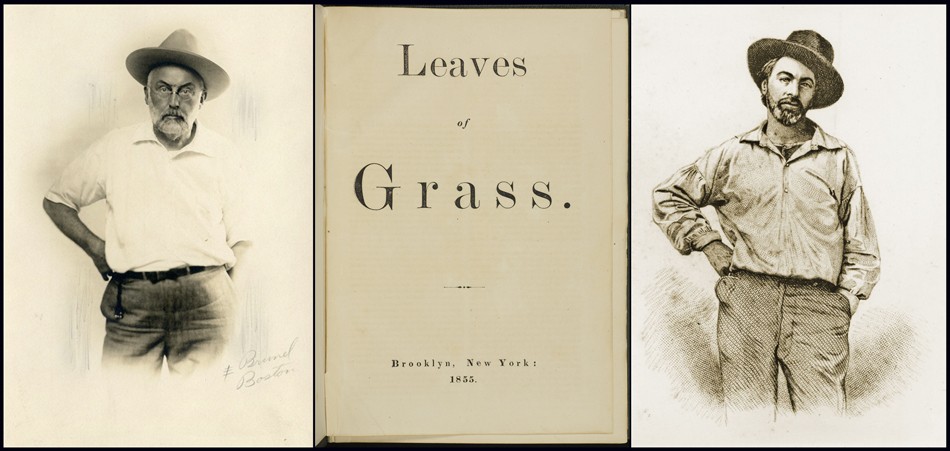

Left: “Gustave Percival Wiksell as Walt Whitman”: Undated gelatin-silver print by Emile Brunel Studio, Boston, ca. 1915-25?: Wearing similar clothing, Wiksell strikes a pose similar to one Whitman made from a lost daguerreotype by Gabriel Harrison later made into a steel engraving by Samuel Hollyer. Boston dentist Gustave Percival Wiksell was an ardent devotee to Walt Whitman and president of the Whitman Fellowship from 1903-19. Photograph © All rights reserved by tackyspoons/flickr. Middle: 1855 first edition title page to Leaves of Grass, Brooklyn, New York. Courtesy The Lilly Library, Indiana University. Right: Original Samuel Hollyer steel engraving of frontispiece portrait of Walt Whitman used for the 1855 and 1856 editions of Leaves of Grass.,Gabriel Harrison’s original 1854 daguerreotype showed the 35-year-old Whitman wearing laborer’s clothing. The Whitman Archive provides the following description of the original sitting: “Of the day the original daguerreotype was taken, Whitman remembered, “I was sauntering along the street: the day was hot: I was dressed just as you see me there. A friend of mine—”Gabriel Harrison (you know him? ah! yes!—”he has always been a good friend!)—”stood at the door of his place looking at the passers-by. He cried out to me at once: ‘Old man!—”old man!—”come here: come right up stairs with me this minute’—”and when he noticed that I hesitated cried still more emphatically: ‘Do come: come: I’m dying for something to do.’ This picture was the result.” Engraving courtesy Bayley Collection: Ohio Wesleyan via Walt Whitman Archive.

But concerning the roundel portrait of Traubel, what a difference between it and the staid portraits published during his lifetime! The seller described it thus: “Vintage Risque Photo Handsome Shirtless Man w/ Love Poem c. 1910 Gay Interest”. If you are a collector like me, the proverbial eye roll is something experienced practically every day in the course of searches for new treasure. To wit: if it’s a photo depicting two men together- or for that matter, two women- a seller might add the descriptor of “Gay Interest” to the listing. This is laughable on the face of it, as to my mind there is often a complete disconnect between reality often taking over the minds of sellers intent on rewriting photographic evidence for the sole purpose of making a quick buck.

But not always. Fortunately for me, and unbeknownst to the seller, I had a hunch who the sitter of this portrait was. My offer accepted, I only later determined “gay interest” was only the tip of the iceberg.

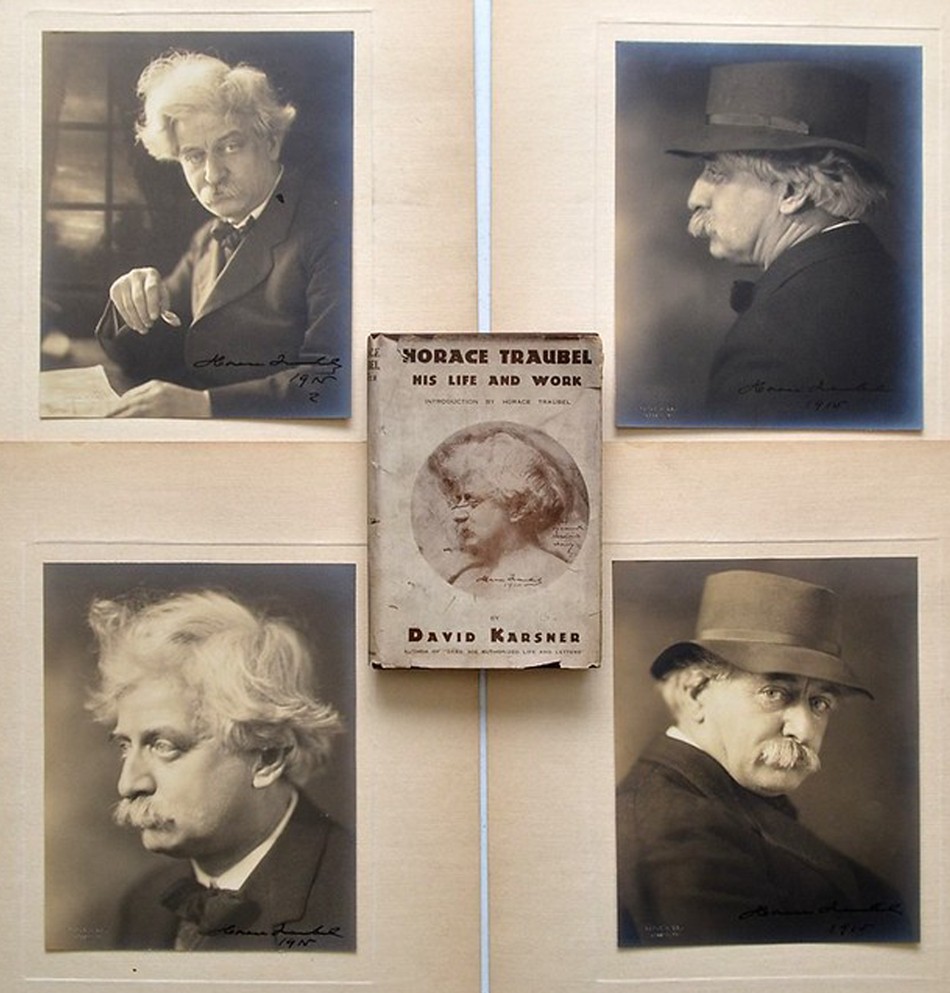

After some sleuthing, I discovered this portrait had seemingly been published only one time in 1919: as the dust-jacket illustration to a limited-edition posthumous work on Traubel written by his biographer David Karsner, a close friend who describes him as part Karl Marx and Jesus of Nazareth, and “in possession of a point of view which issues a labor-conscious ‘warning and challenge.” (2.)

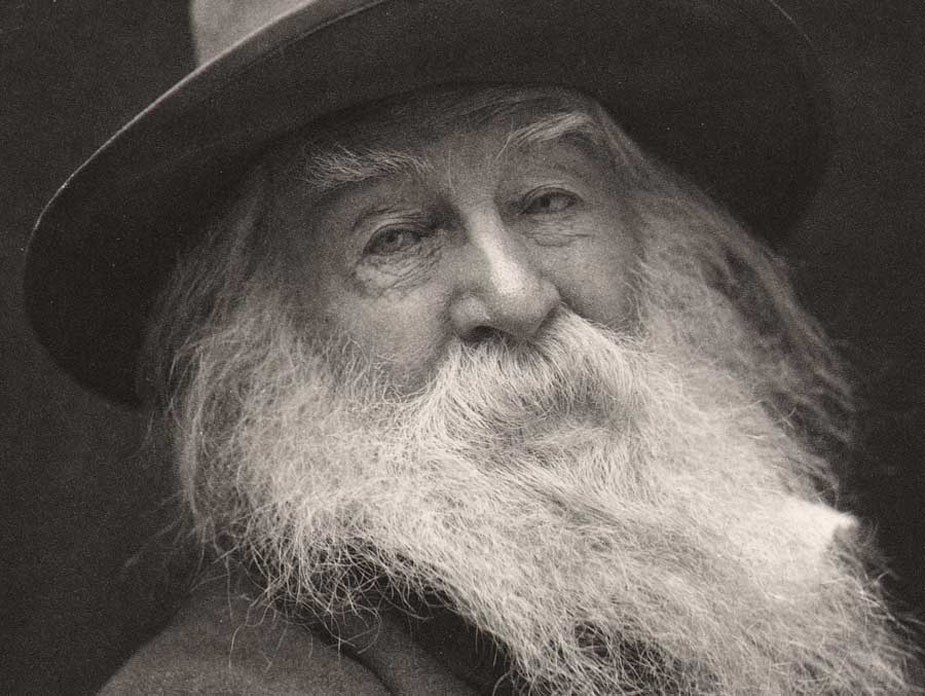

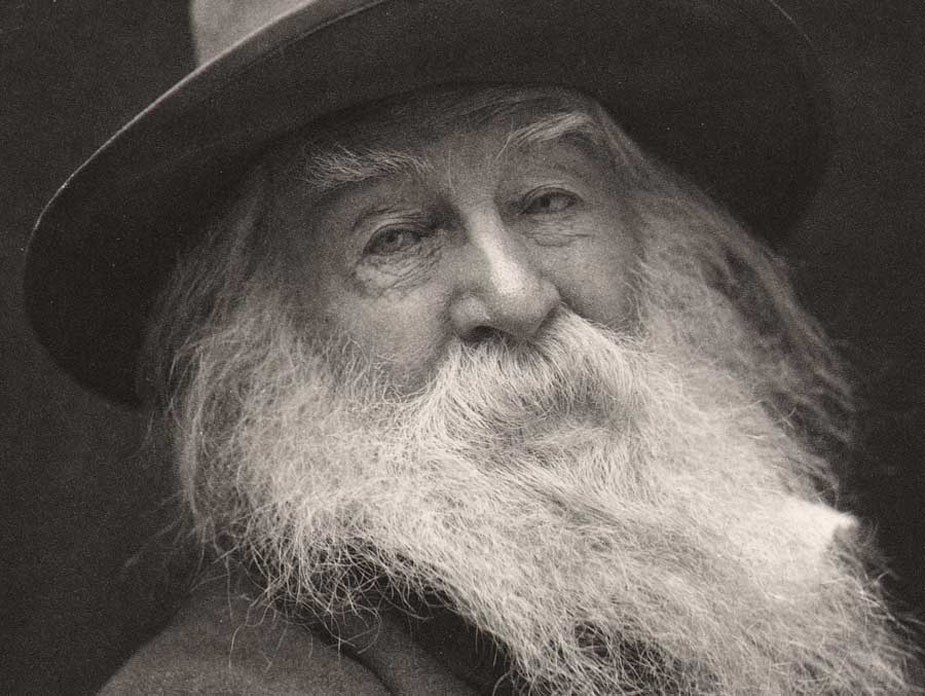

Detail: 1887: Walt Whitman-1819-1892 by George C. Cox: (portrait known as the “Laughing Philosopher”) 23.9 x 18.8 cm | 45.2 x 33.3 cm: vintage large format, hand-pulled photogravure printed circa 1905-10 by the Photographische Gesellschaft in Berlin on Van Gelder Zonen plate paper. From: PhotoSeed Archive

But unlike the aforementioned staid portraits, which always show him wearing a shirt or jacket- this profile view was unusual for the time in which it was made- 1910-bare-shouldered, and thus sans shirt. When I finally made out the signature of the person this particular print was dedicated to-personally inscribed by the sitter on the print surface recto to someone named “Wiksell” in the upper left corner, it all came together. For on the inside cover of the folder in which this portrait appears (when purchased it was framed) Traubel has inscribed several lines- a love poem, if you will, confirming the sellers hunch, “For Percival Wiksell- 1910” :

You don’t know me? I do not wonder: I dont know myself: I am at a loss about myself:

You ask: who are you? and I shake my head : I look at you and say nothing:

I come to you but I could not tell why: I have something for you but I could not tell what:

Out of me some flower will blossom out of my seedthrow some harvest will come. – Horace Traubel

(From Optimos: “I Just Give You What I’ve Got”- 1910)

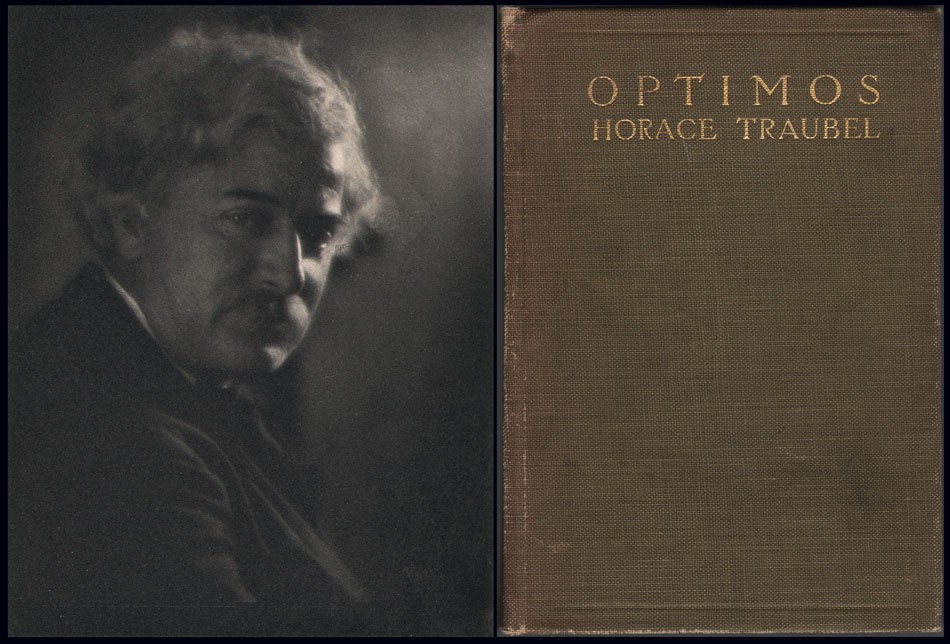

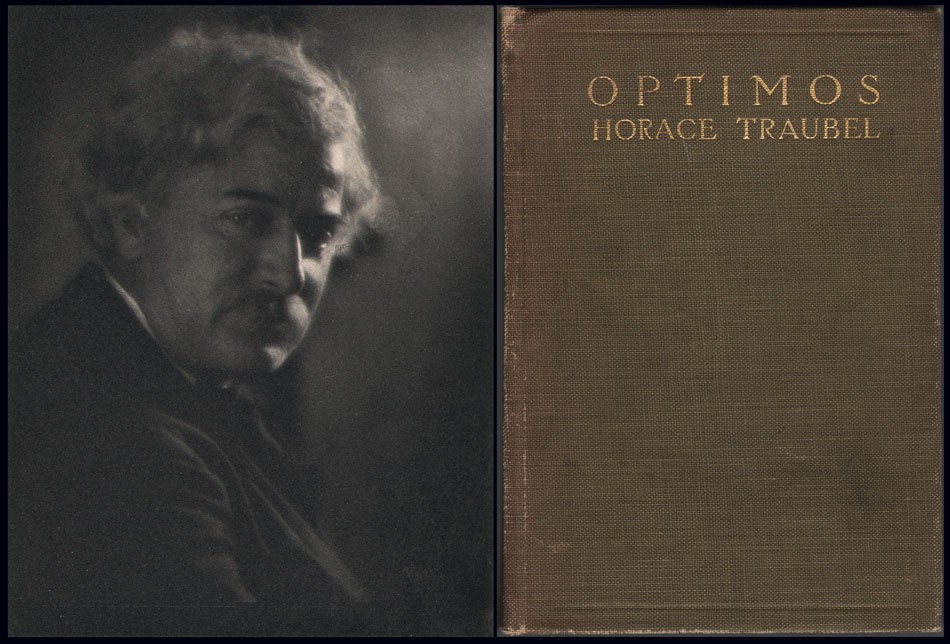

Left: “Frontispiece Portrait of Horace Traubel” (1909) from the book of poetry “Optimos”: Clarence H. White, American: 1910: photogravure: 11.4 x 8.7 | 18.7 x 12.5 cm. From scholar Anne McCauley’s 2017 volume “Clarence H. White and His World: the Art and Craft of Photography, 1895-1925 we learn” : “Reynold’s (Stephen Marion Reynolds (1854-1930) a lawyer who joined the Social Democratic Party in 1900-ed) and Traubel’s recognition of photography as a powerful tool in the class struggle, whether in the form of the dissemination of the fine arts or as a creative means of personal expression if transformed by hand manipulation, caused them to appreciate White’s skills as well as his openness to their political opinions.” (p. 178) Right: Front Cover of “Optimos”, the best-known volume of poetry by Horace Traubel: New York: 1910: B.W. Huebsch (8vo | olive green cloth) From the Walt Whitman Archive online resource, “His own books can be read as socialist refigurings of Whitman’s work, each of his titles subtly adjusting Whitman’s terminology: …Optimos (1910) redefined Whitman’s “kosmos” as an optimized “cheerful whole” (qtd. in Bain 39). And although some in his day declared Traubel as a poet to be Whitman’s successor, there were plenty of critics. Writing in the pages of The Smart Set for July, 1911 under the heading “Novels for Hot Afternoons”, American critic H.L. Mencken, said of “Optimos”: “Horace Traubel fills the three hundred and more pages of his “optimos” (Huebsch) with dishwatery imitations of Walt Whitman, around whom Horace, in Walt’s Camden days, revolved as an humble satellite. All of the faults of the master appear in the disciple. There is the same maudlin affection for the hewer of wood and drawer of water, the same frenzy for repeating banal ideas ad nauseam, the same inability to distinguish between a poem and a stump speech. Old Walt, for all his absurdities, was yet a poet at heart. Whenever he ceased, even for a brief moment, to emit his ethical and sociological rubbish, a strange beauty crept into his lines and his own deep emotion glorified them. But not so with Horace. His strophes have little more poetry in them than so many college yells, and the philosophy they voice is almost as bad as the English in which they are written.” From: PhotoSeed Archive

The recipient, Gustave Percival Wiksell, (1863-1940) was a Boston dentist who served as president of the Walt Whitman Fellowship from 1903-1919. So devoted was this disciple to the master that he went to the length of replicating the now famous pose Whitman took from a now lost 1854 daguerreotype by Gabriel Harrison made into an engraving and used as the frontispiece illustration for the 1855 & 1856 editions of Whitman’s masterpiece Leaves of Grass.

Wiksell’s papers are now in the Library of Congress in Washington and he was known to have eulogized Horace Traubell at his funeral in 1919. More than one Traubel scholar lays out the evidence that Wiksell and he were more than good friends, but I will leave that for your own further inquiries. (further attribution can be found in a cutline with this post)

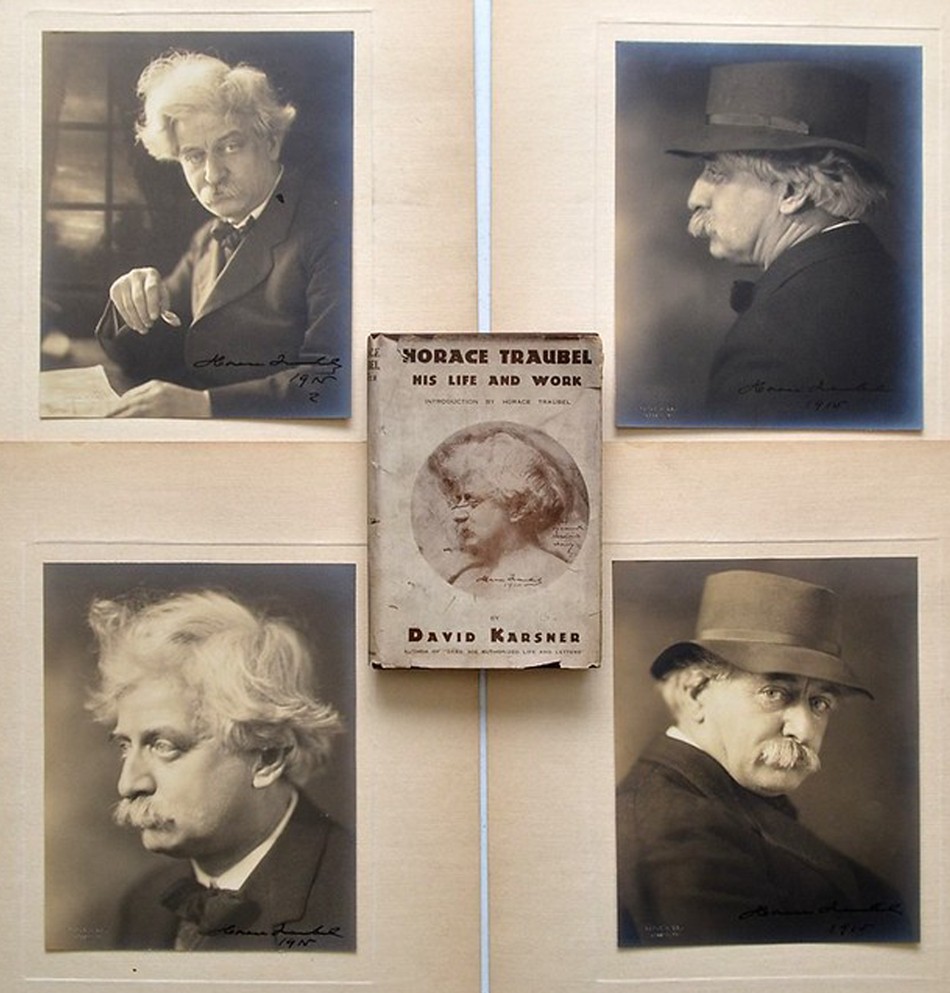

“Ca. 1915 signed and mounted portraits of Horace Traubel” (unknown photographer) surrounding at center: “Horace Traubel: His Life And Work” by David Karsner (New York: Egmont Arens, 1919) with elusive dust-jacket reproducing bare-shouldered 1910 portrait “Horace Traubel: Roundel Portrait”. Commentary on Traubel by Karsner appeared in the online resource Poetrybay in the Fall of 2009: “On the other hand David Karsner, Traubel’s biographer… called him “a poet and prophet of the new democracy.” Traubel, suggests Karsner, is part Karl Marx and part Jesus of Nazareth, and in possession of a point of view which issues a labor-conscious ‘warning and challenge.” From Wikipedia: David Fulton “Dave” Karsner (1889–1941) was an American journalist, writer, and socialist political activist. Karsner is best remembered as a key member of the editorial staff of the New York Call and as an early biographer of Socialist Party of America leader Eugene V. Debs. Photographic grouping courtesy The Library of William F. Gable Auction: Savo Auctioneers, Archbald, PA: January 3, 2015.

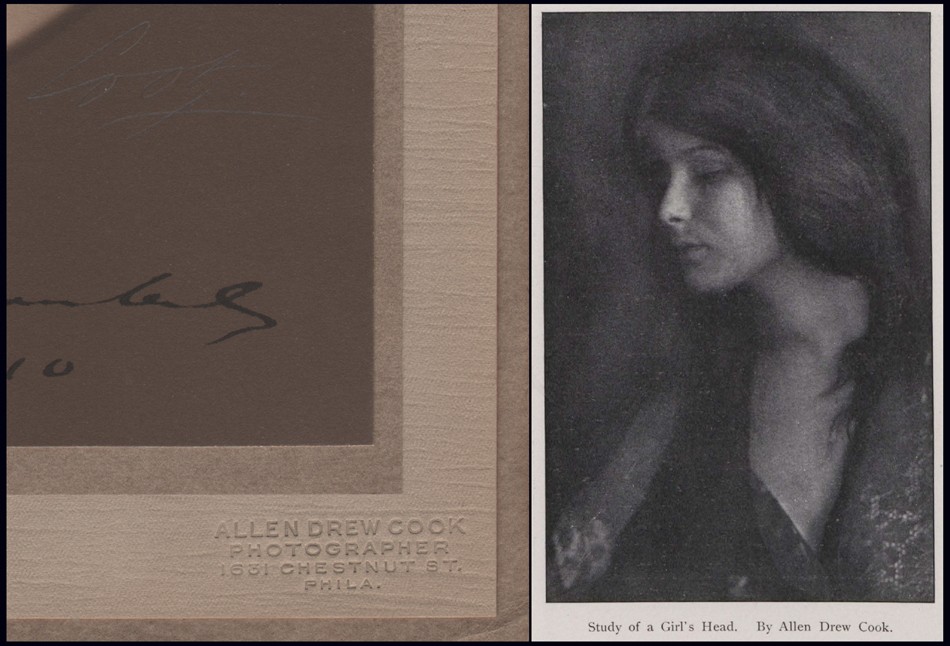

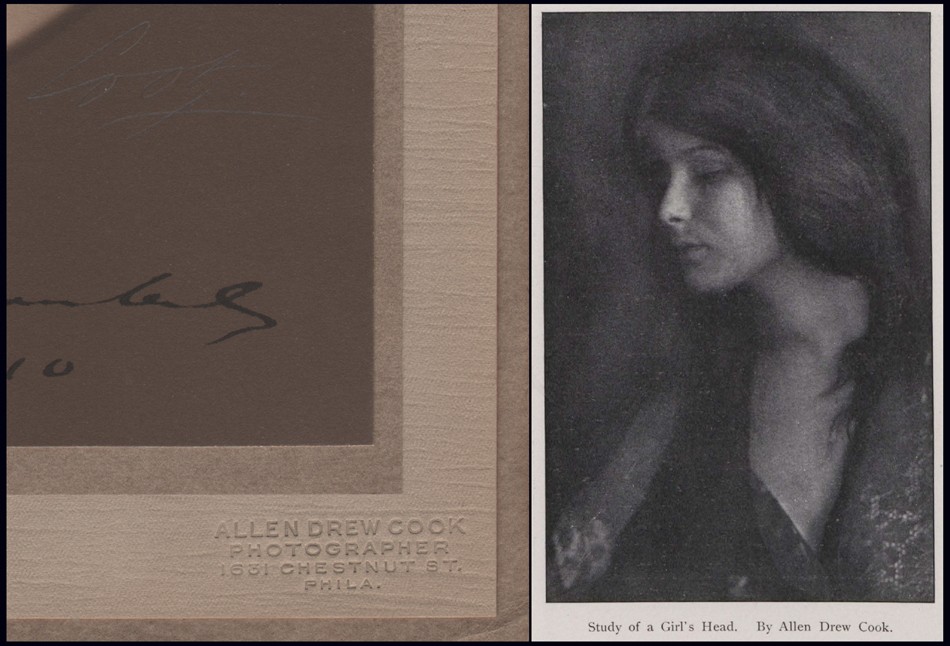

Left: Detail showing blind-stamp for photographer Allen Drew Cook on secondary mount to photograph “Horace Traubel: Roundel Portrait”: Allen Drew Cook, American (1871-1923): 1910: mounted platinum print contained within folder: 17.4” roundel on paper 23.7 x 19.6 cm; supports: 24.8 x 20.6 | 28.4 x 23.9 cm. In upper left of detail is seen graphite signature: “Cook”, underlined outside lower margin of roundel; the blind-stamp additionally lists his address as 1631 Chestnut St. in Philadelphia- the same as for the offices of the The Conservator, a monthly literary magazine edited and published by Horace Traubel beginning in October, 1910. (the magazine, which was started in 1890, previously lists its’ address as 1624 Walnut St. in Philadelphia.) Beginning In 1915 and running into 1916, an advertisement for “Photographic Portraits” by Allen Drew Cook of Eugene Debs, Clarence Darrow, J. William Lloyd and Traubel appeared on the back page of The Conservator. From: PhotoSeed Archive. Right: “Study of a Girl’s Head”, from around 1900, is an early example of a pictorialist photographic portrait entered by Cook in the Third Annual Philadelphia Photographic Salon and reproduced as a halftone in the Salon’s 1900 catalogue. Courtesy: Thomas J. Watson Library Digital Collections – The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Five years ago on July 4th, America’s birthday, I published a post featuring several vintage likenesses of Walt Whitman- “Oh Say Can you See?” and his importance to capturing the enduring spirit of our country. In this, Traubel certainly will never be magically rediscovered as the good gray poet’s literary successor (none other than H.L. Mencken derided his poetry as “dishwatery imitations of Walt Whitman, around whom Horace, in Walt’s Camden days, revolved as an humble satellite.”) (3.) But his ideals as one spreading love as written in the lines at the top of this post-a socialist ideal in the vein of Whitman- are surely honorable and needed in the fractured American present. Instead of cleaved partisan camps and tribes seemingly taking over our national conversation, how about a bit more love comrades? Socialism has nothing to do with that last word, by the way. Instead, let’s celebrate the ideals of our national melting pot, and give all her citizenry power to the truth of her motto: “E Pluribus Unum” – Out of Many, One.

Just what Horace would have wanted.

Notes:

1. Excerpt: The Guardian (online): Julianne McShane: “Walt Whitman: celebrating an extraordinary life in his bicentennial”: June 12, 2019. One hundred thirty photographic portraits of Walt Whitman have been identified to date.

2. Excerpt: Online resource Poetrybay: Fall, 2009: commentary on Traubel by Karsner.

3. Excerpt: Review: “Optimos” : “Novels for Hot Afternoons”: H.L. Mencken: The Smart Set: July, 1911.