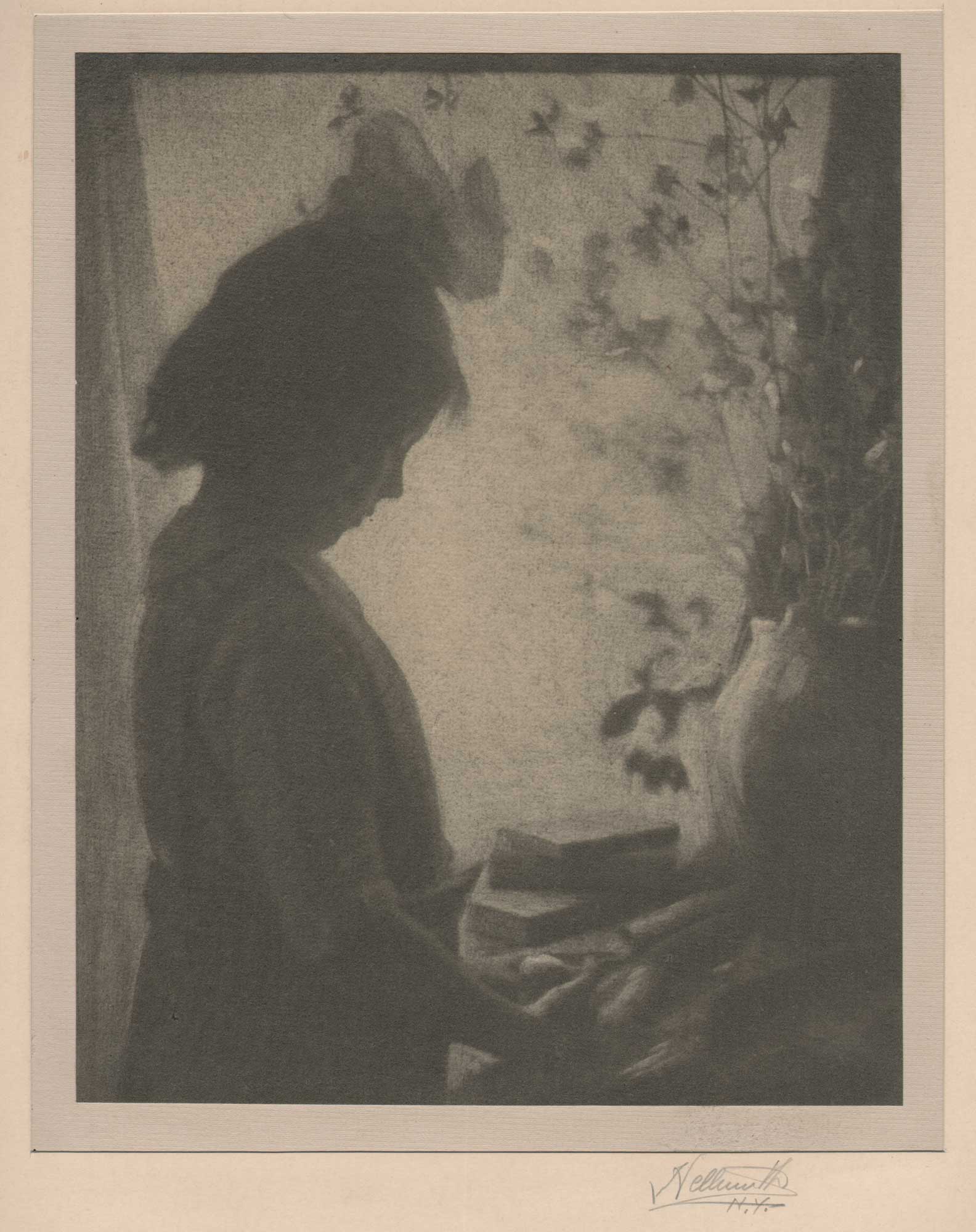

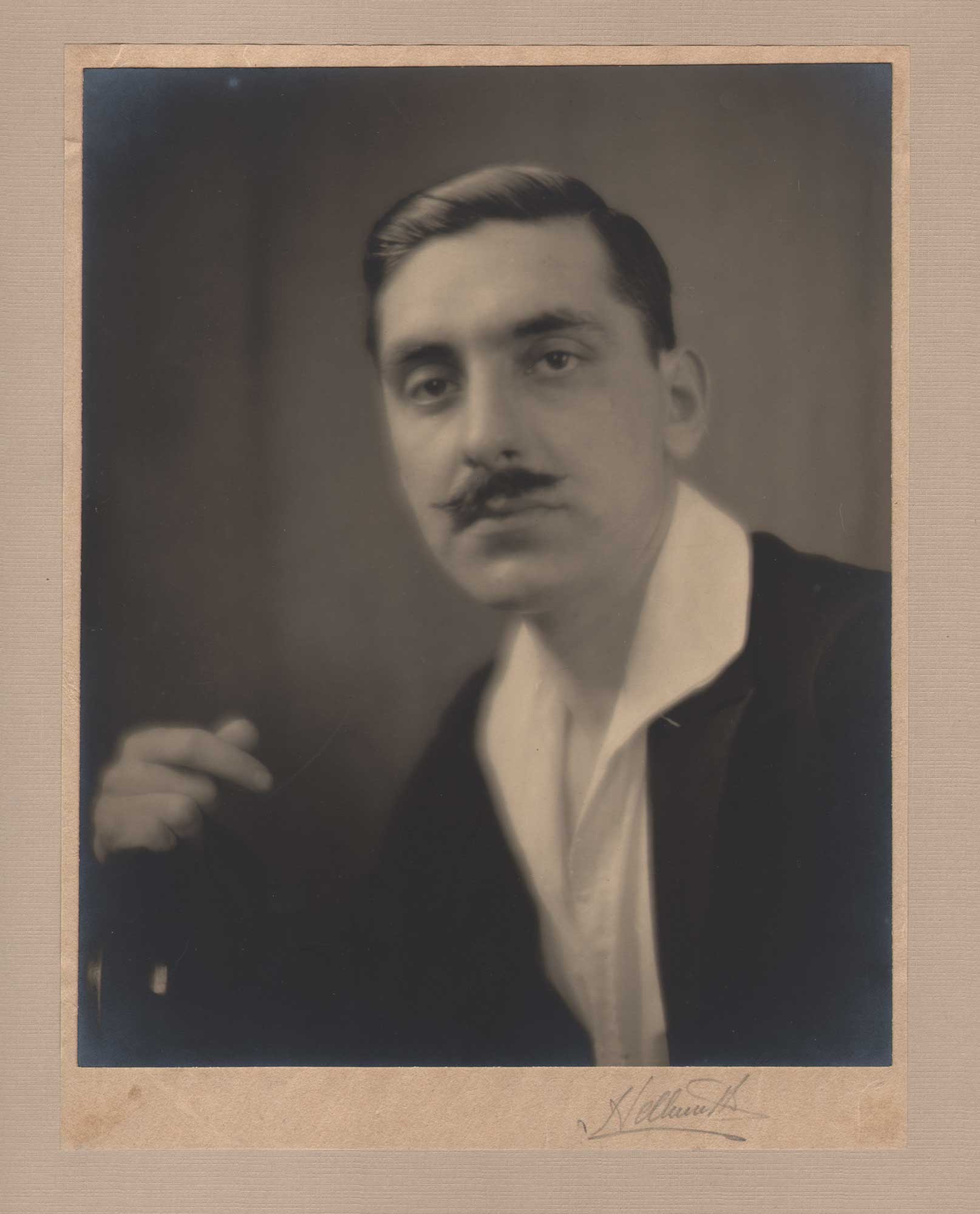

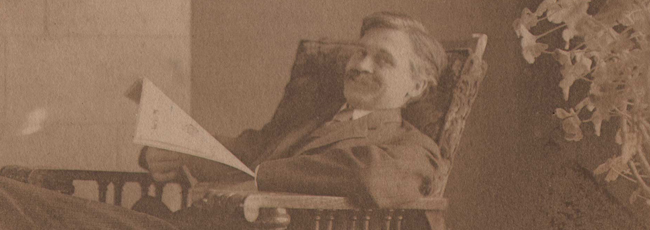

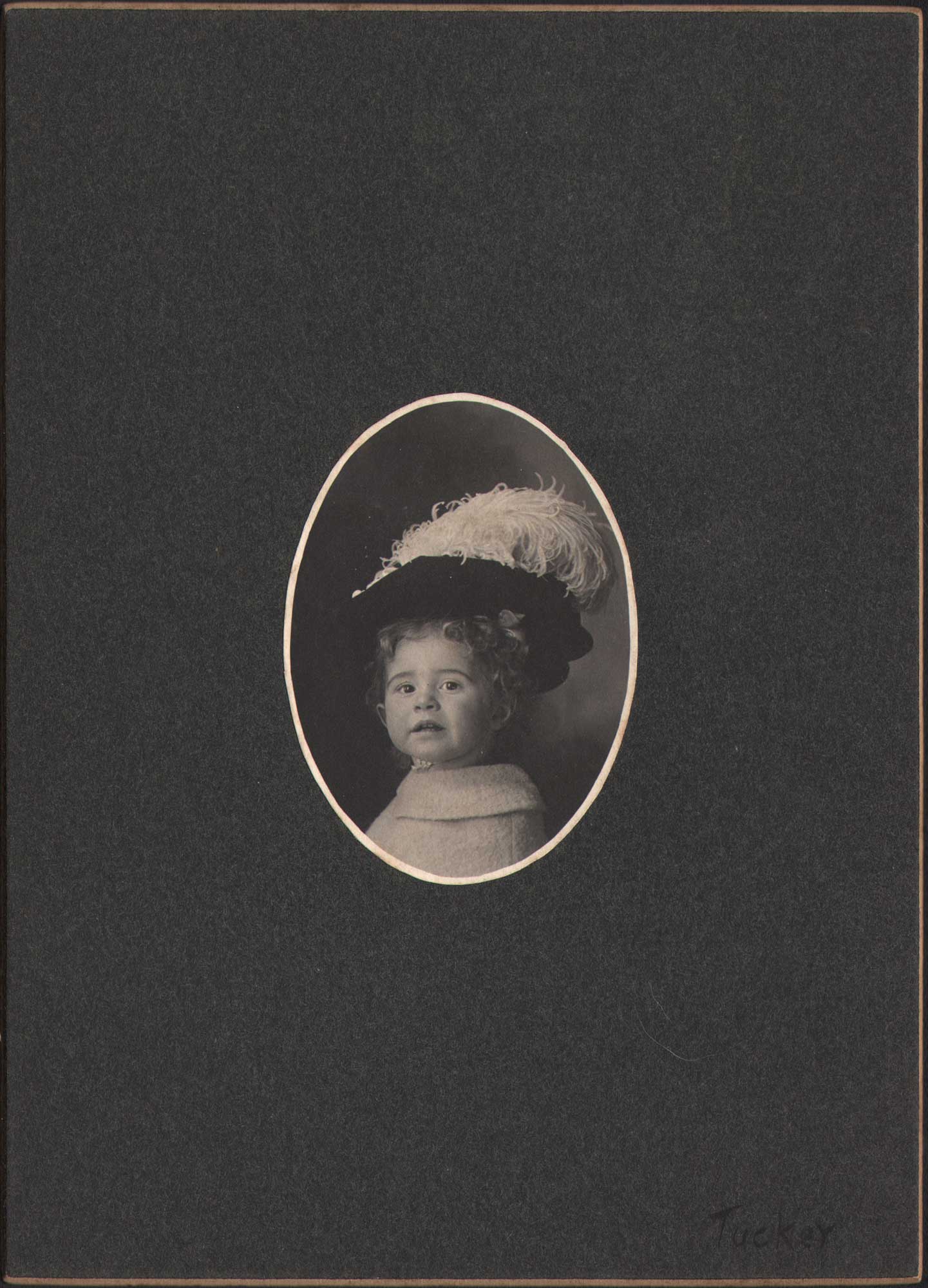

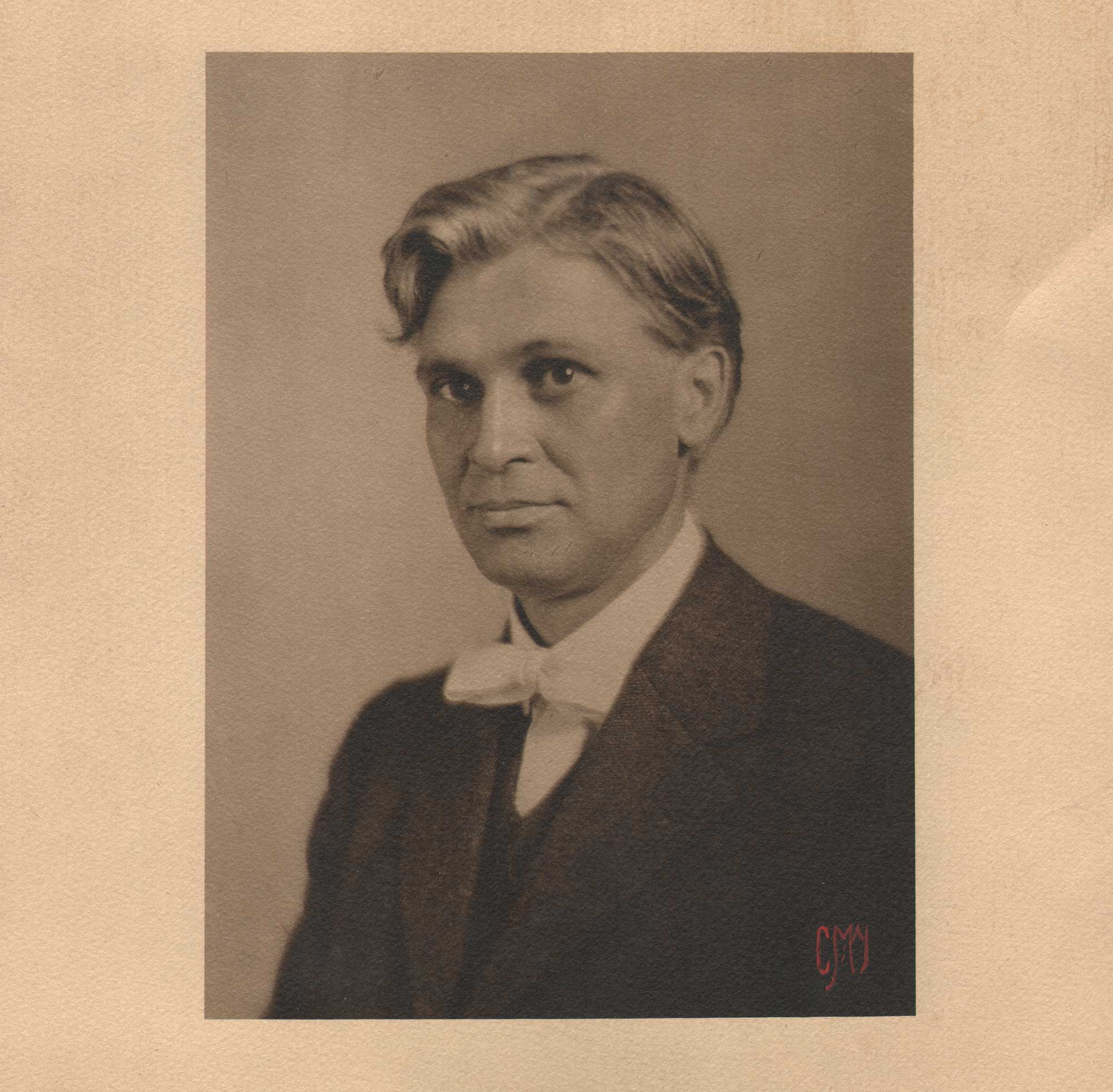

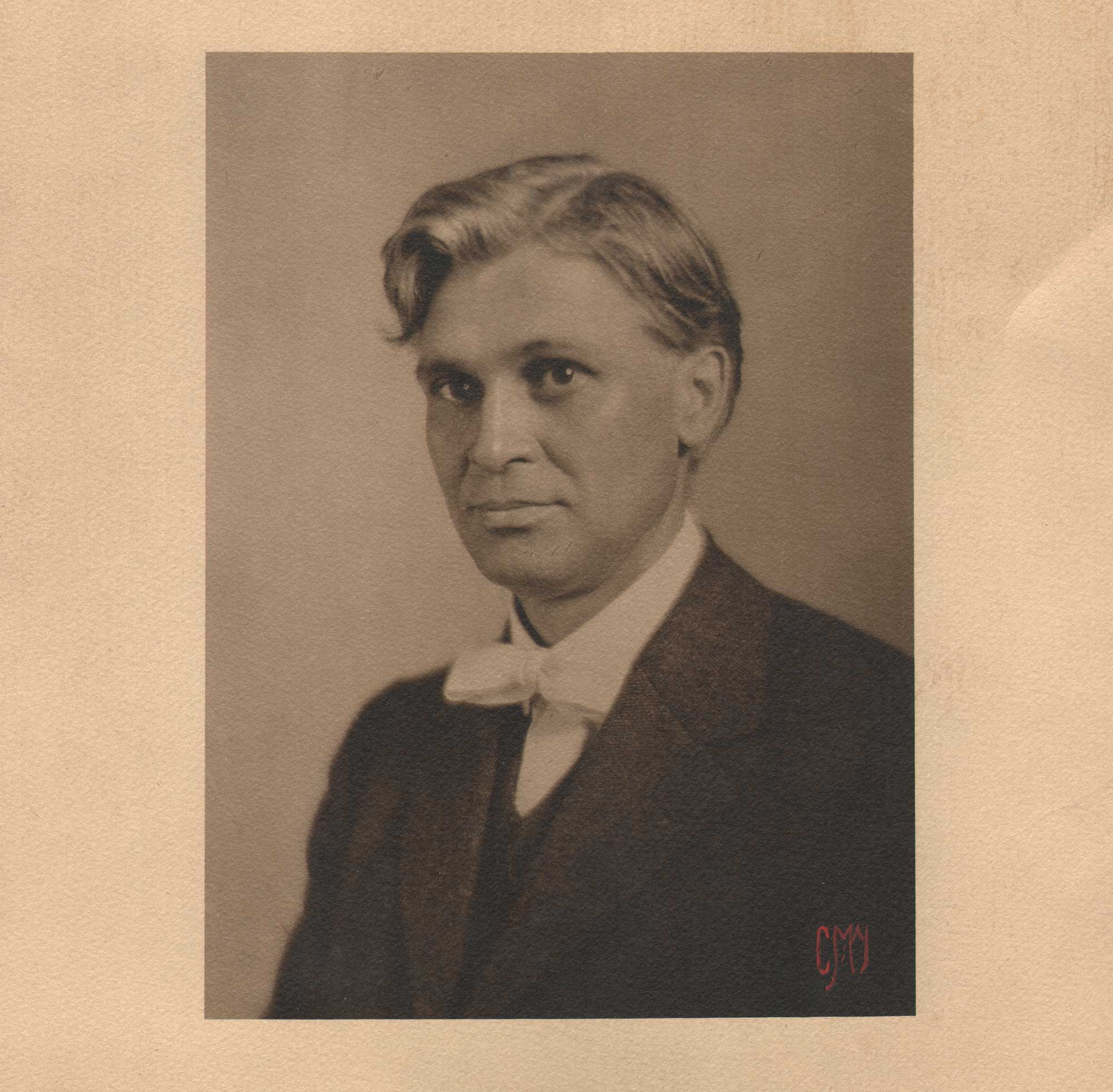

“Portrait of Charles Rollins Tucker”, Chester Moulton Whitney, American: 1873-1949, Bromide print mounted within folder, ca. 1910, 18.9 x 13.9 | 29.6 x 22.7 cm | 31.1 x 47.4 cm-opened. This formal portrait of C.R. Tucker was taken during the time he was teaching physics at Curtis High School on Staten Island. In addition to sharing a love for amateur photography, Whitney and Tucker were good friends and their family socialized together. Several surviving photos show Whitney’s young son playing with Tucker’s daughter Dorothy at the Tucker home in New Dorp. Both natives of MA and public school teachers, the Alden Letter from 1949 mentioned Tucker had spent a week with “Mr. Whitney” at his summer home in Boothbay Harbor, ME in August of that year, the same year Whitney passed. From: PhotoSeed Archive

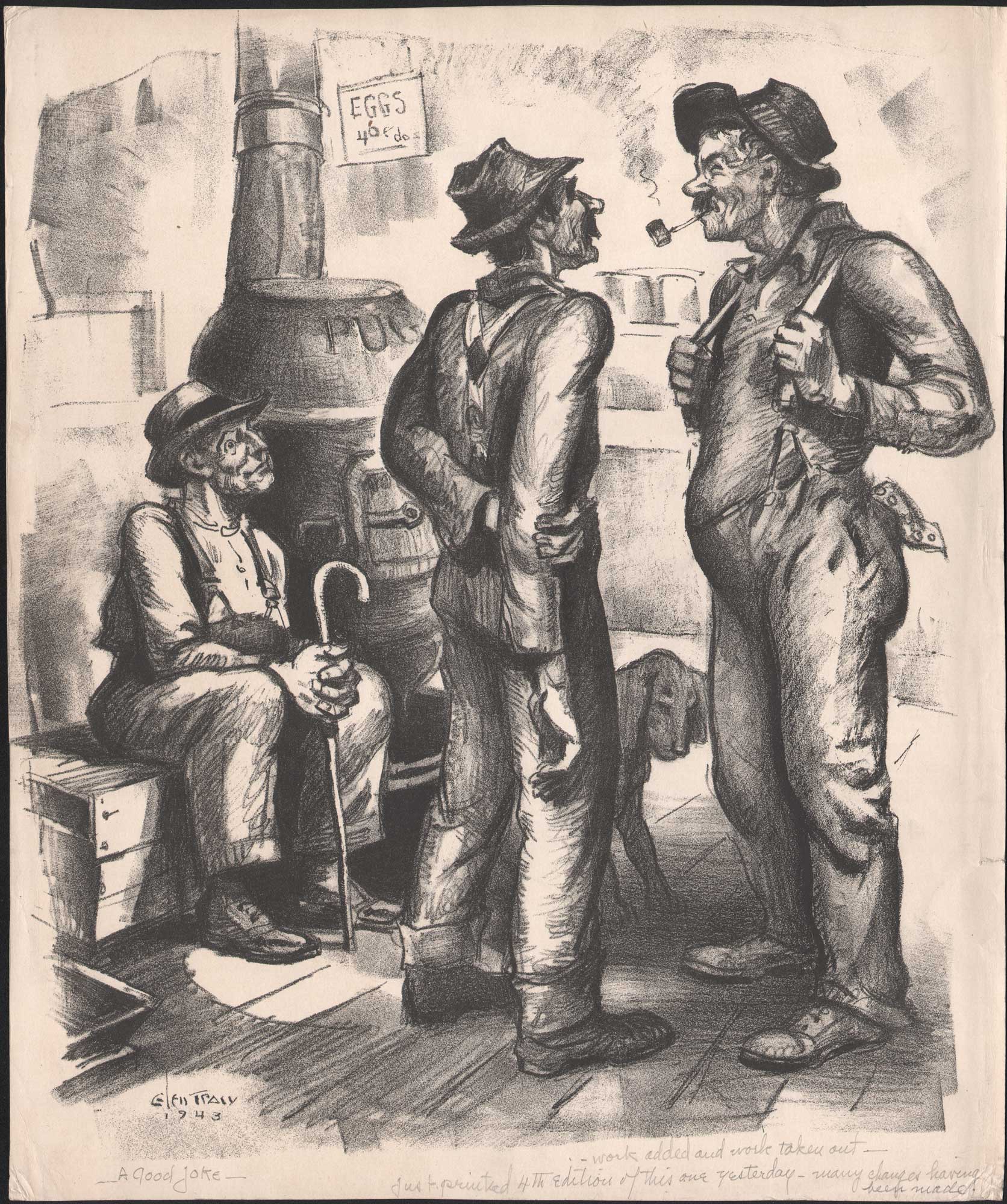

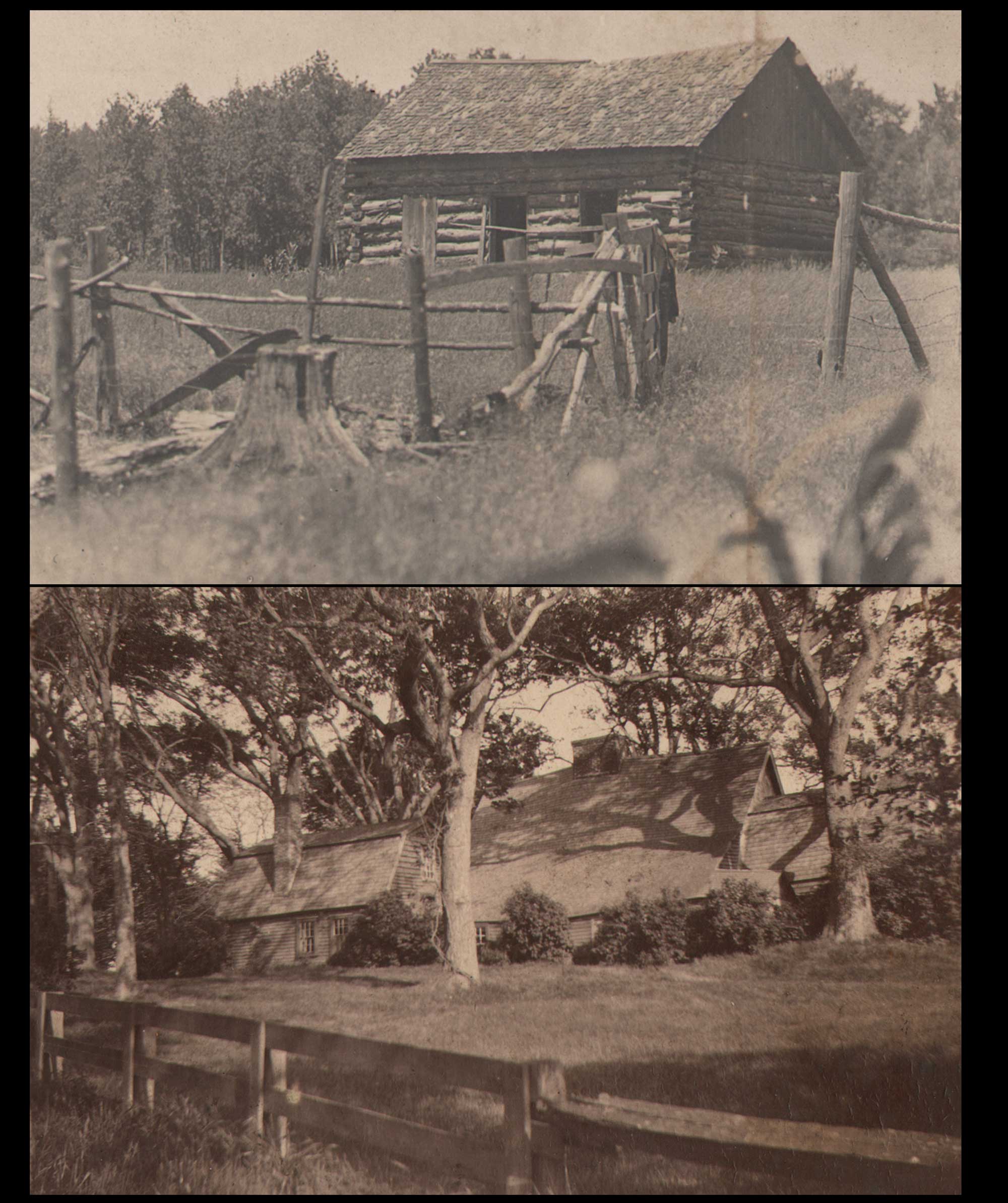

This is the first of a two-part blog post: Revealed: C.R. Tucker: Restless Wanderer with a Camera. It uncovers a life once lost to history: the fascinating story of public school educator and amateur photographer Charles Rollins Tucker, 1868-1956. Our post concludes with an in-depth historical timeline of Tucker’s life. For fifteen years, since acquiring an archive of his work, I’ve been wanting to do a deep-dive into the life of American amateur photographer C.R. Tucker. Perhaps the most important role of this website is to uncover the past lives of anonymous photographers, whose life details have been entirely lost to history. It’s not that he was some lost genius behind the camera, say in the mold of the acknowledged masters of the medium: those have already been, and continue to be, documented and celebrated in the historical canon. In this vein, and to its credit as a medium that continually fascinates by revealing secrets with a bit of digging, Tucker’s photographic life story- began around the time he graduated high school in 1887- can give all of us a relatable way to see how a hobby born 138 years ago can be a life-long journey of exploration rather than a short term dalliance.

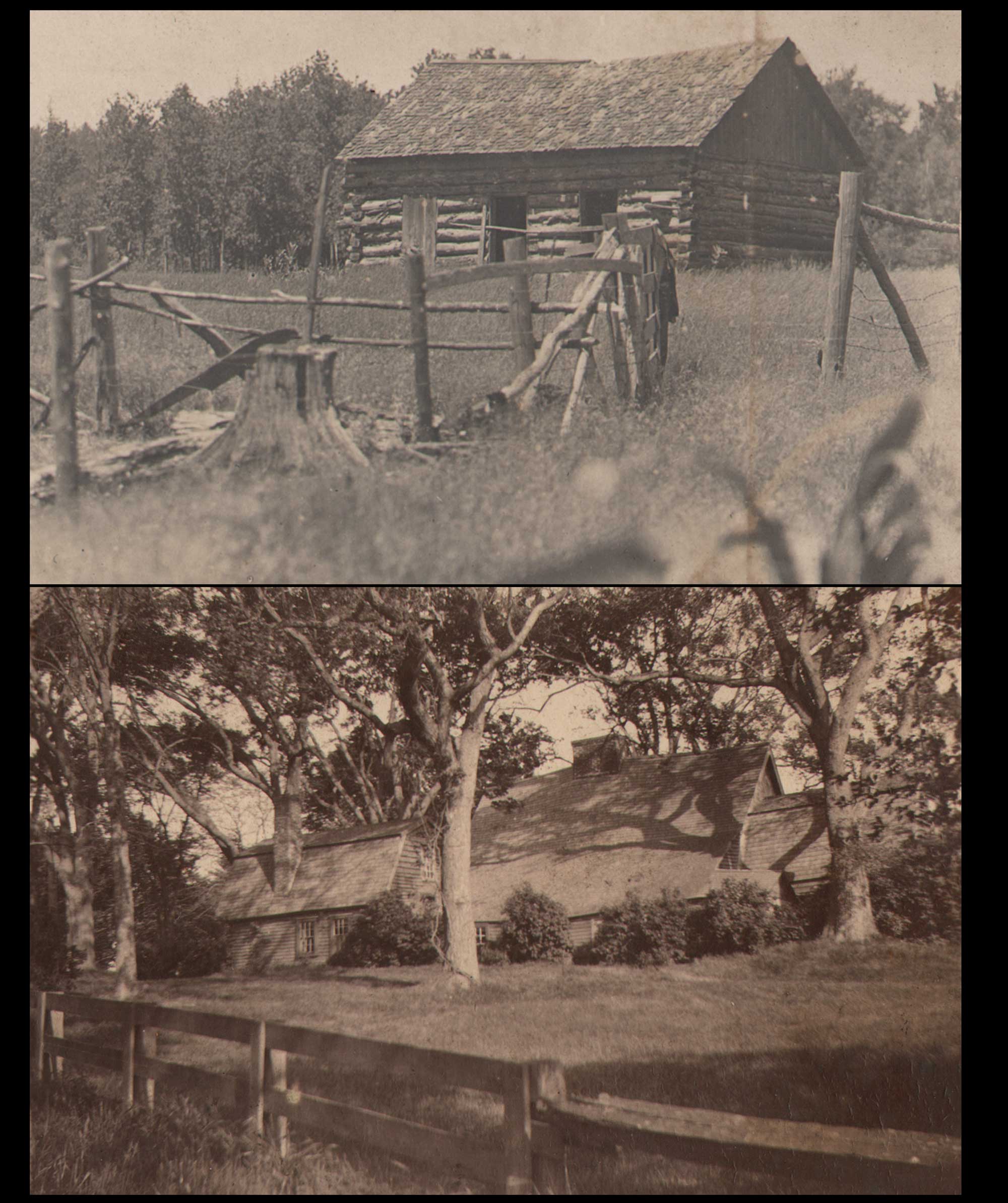

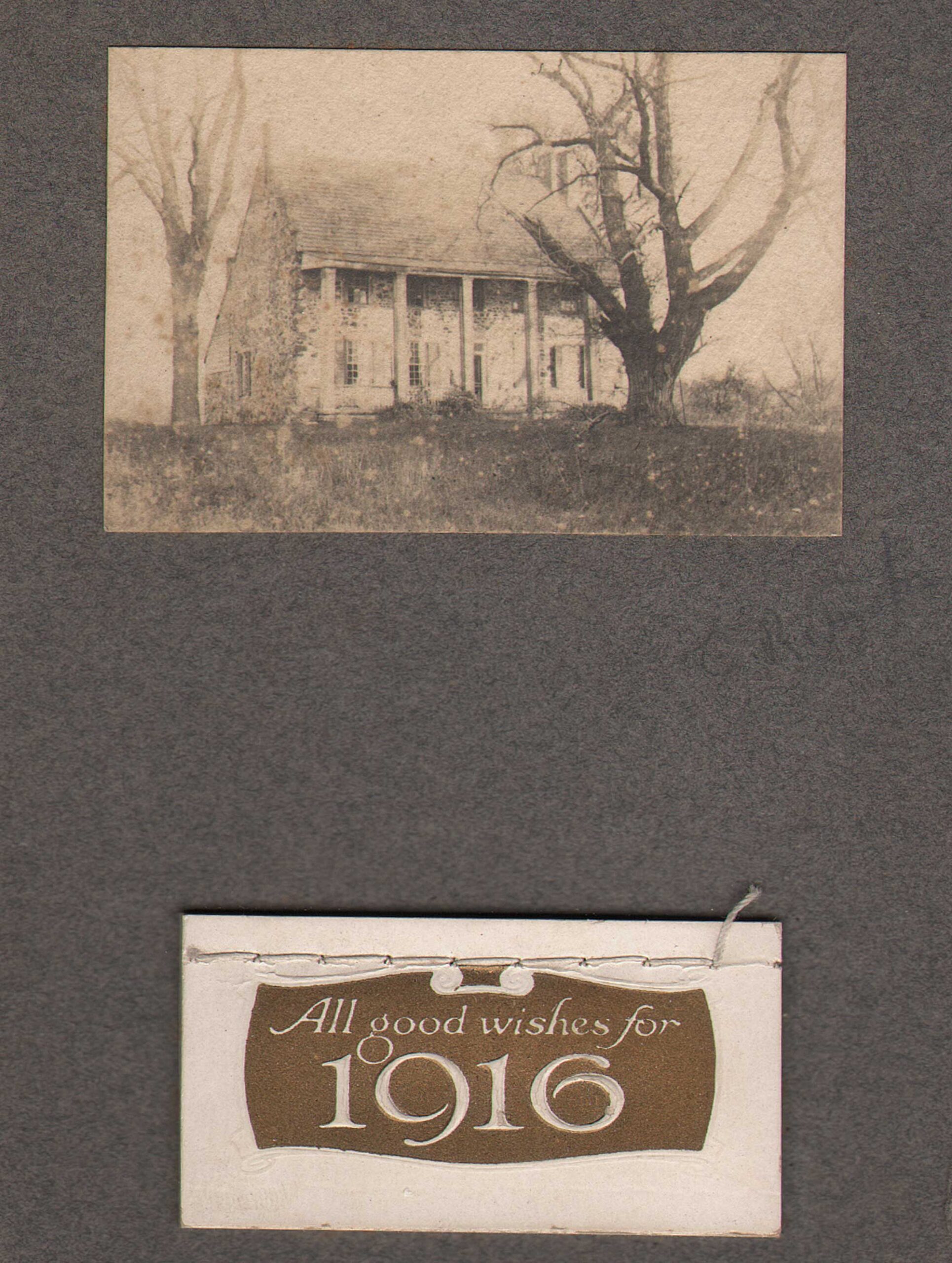

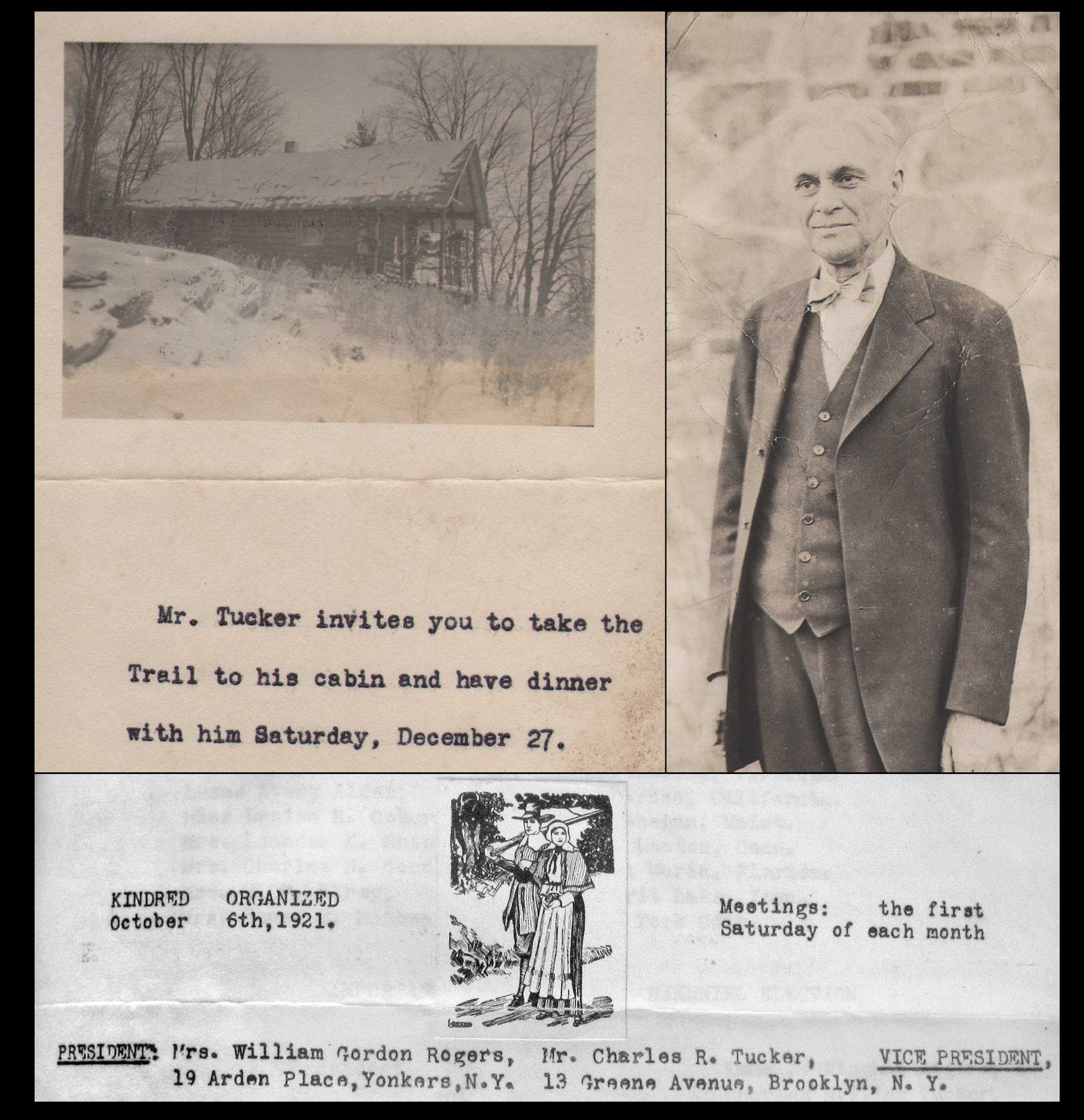

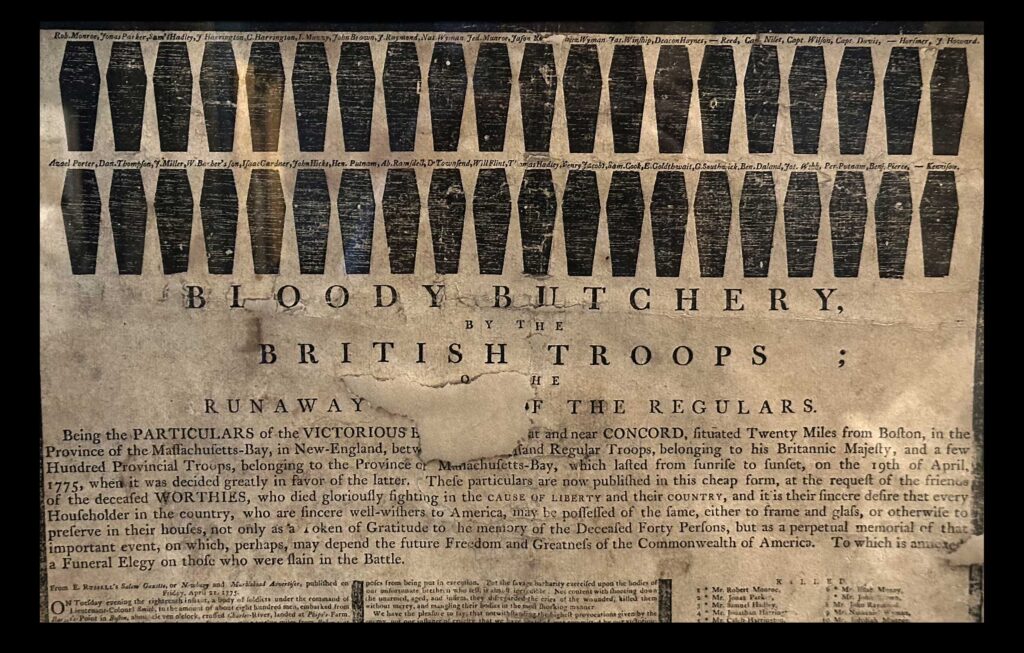

New & Old. Top: “My Old Log House in WI”, ca. 1908, gelatin silver rppc post card, photo credit to C.R. Tucker’s mother Myra Tucker on verso, 8.3 x 13.4 cm. Amateur photographer C.R. Tucker lived in this Wisconsin log cabin for five years, from about 1873-1878 before going back to New England at 10 years of age to complete his schooling. Bottom: “Fairbanks House”, C.R. Tucker, American: 1868-1956, albumen print on card, ca. 1885-1890, 8.8 x 10.9 | 10.0 x 15.1 cm. Dating to 1641, this is the oldest surviving timber-frame house still standing in North America. From: PhotoSeed Archive

The fact that so much photographic history has been lost, an area I expound upon in the second part of this post, makes the rare opportunity to examine but one of these early lives in greater detail based on the remains of that photographic record- water staining, mildew and the effects of improper storage on some of these images seen here being besides the point- an anomaly I wanted to celebrate.

What drove my interest further in discovering and piecing together C.R. Tucker’s life story was that his own career of someone who made his living- not in photography- but as a public school educator for about 45 years- is a realistic example of what dedicated amateurs faced in the early years of the medium, particularly during the Pictorial era of artistic photography.

“Stoughton, MA High School Students”, 1887, silver albumen print- 11.0 x 19.4 | 20.4 x 25.4 cm on card mount.This group photograph, thought to have been taken by C.R. Tucker, (American: 1868-1956) includes several classes, as the 1887 graduating class was only 15 students. Based on a guess, this archive thinks Charles Tucker is shown in the front row, third from left. Another possibility? The student seated on a chair leaning against the tree to the left of the teacher standing at back row right. In September, 1887, Tucker would matriculate at Tufts College, in the “Philosophical course”. From: PhotoSeed Archive

This main hurdle of course, was cost. Beyond the simplified “you press the button, we do the rest” mantra, which of course revolutionized the massive participation in making photography a popular hobby, required a good bit of money. Think: home dark rooms, a more expensive plate camera, mounting supplies, postage fees for entering competitions, subscriptions to photographic magazines, etc. etc. And this of course did not include the most valuable component: the cost of someone’s free time to be deliberate and open to learning about photographic process and technique needing plenty of time to perfect and master.

“Moving Jumbo into Barnum Museum, 1889” (title assigned by Tufts University Archives- see variant: ID: tufts: UA136.002.DO.00823 ): Attributed photographer: Charles Rollins Tucker, American, 1868-1956, 1889: mounted brown-toned gelatin silver print on cabinet card: 8.3 x 11.0 cm | 10.8 x 13.2 cm. This rare photograph taken on April, 3 1889 shows the famed circus elephant Jumbo, (died 1885) once owned by circus showman P.T. Barnum. The taxidermied pachyderm was in the process of being moved inside the brand new Barnum Museum of Natural History on the Tufts College campus in Medford, MA, where it was placed on display. From: PhotoSeed Archive.

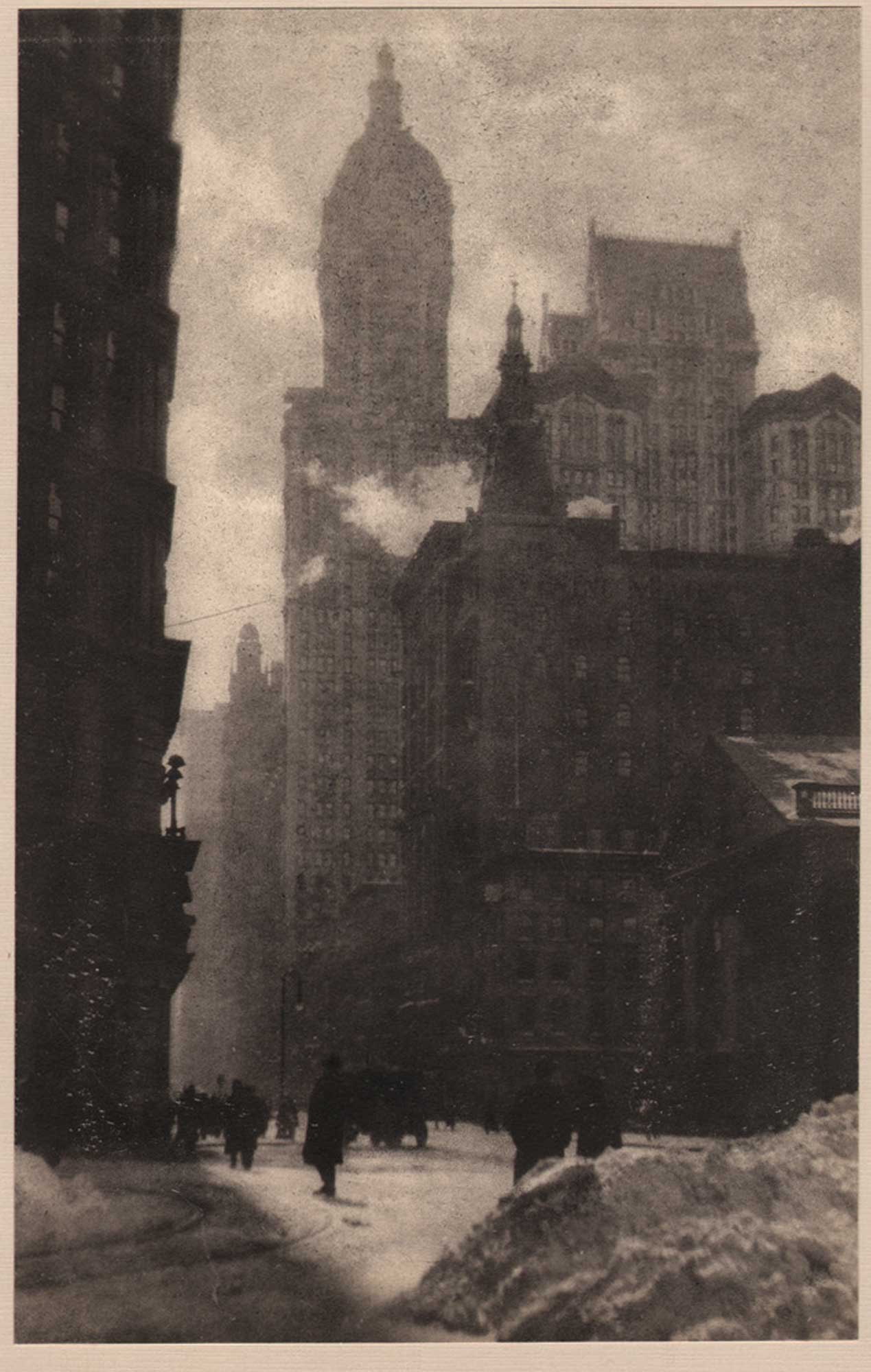

Fortunately, C.R. Tucker had the perfect mind and circumstance to take this all on, and his love for history made him an ideal vessel to create historical documents that are the very definition of photographs themselves. That mind? He was a scientist in practical terms but historian at heart. Born in Canton, MA in 1868, and one of only two to graduate from his small town Massachusetts high school in 1887, he went on to receive both his bachelors and masters degrees from Tufts College outside of Boston. These were entirely complimentary for an advanced amateur photographer for that era: in 1891, a bachelors in the speciality of chemistry and physics and in 1894, a master of arts degree.

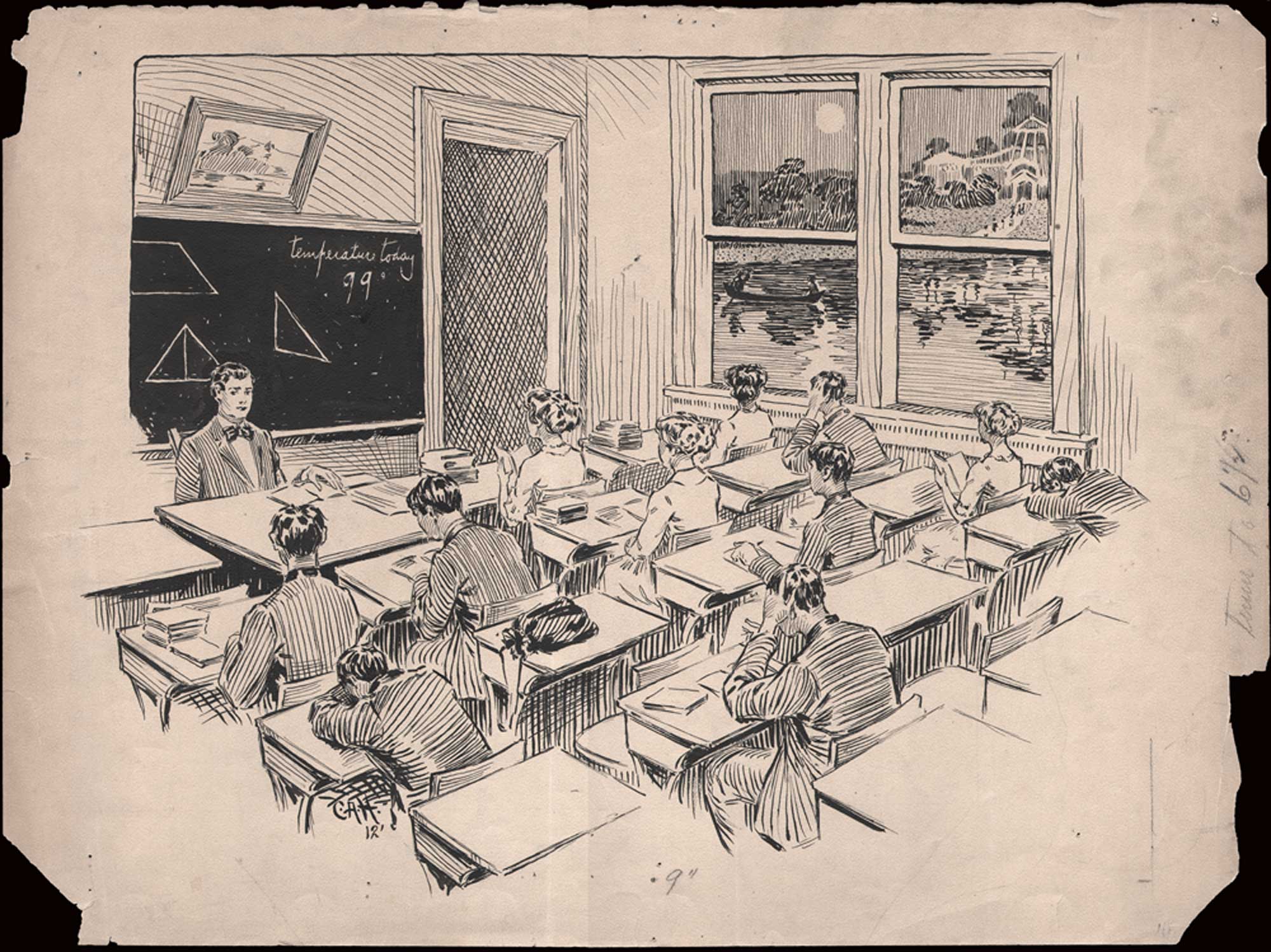

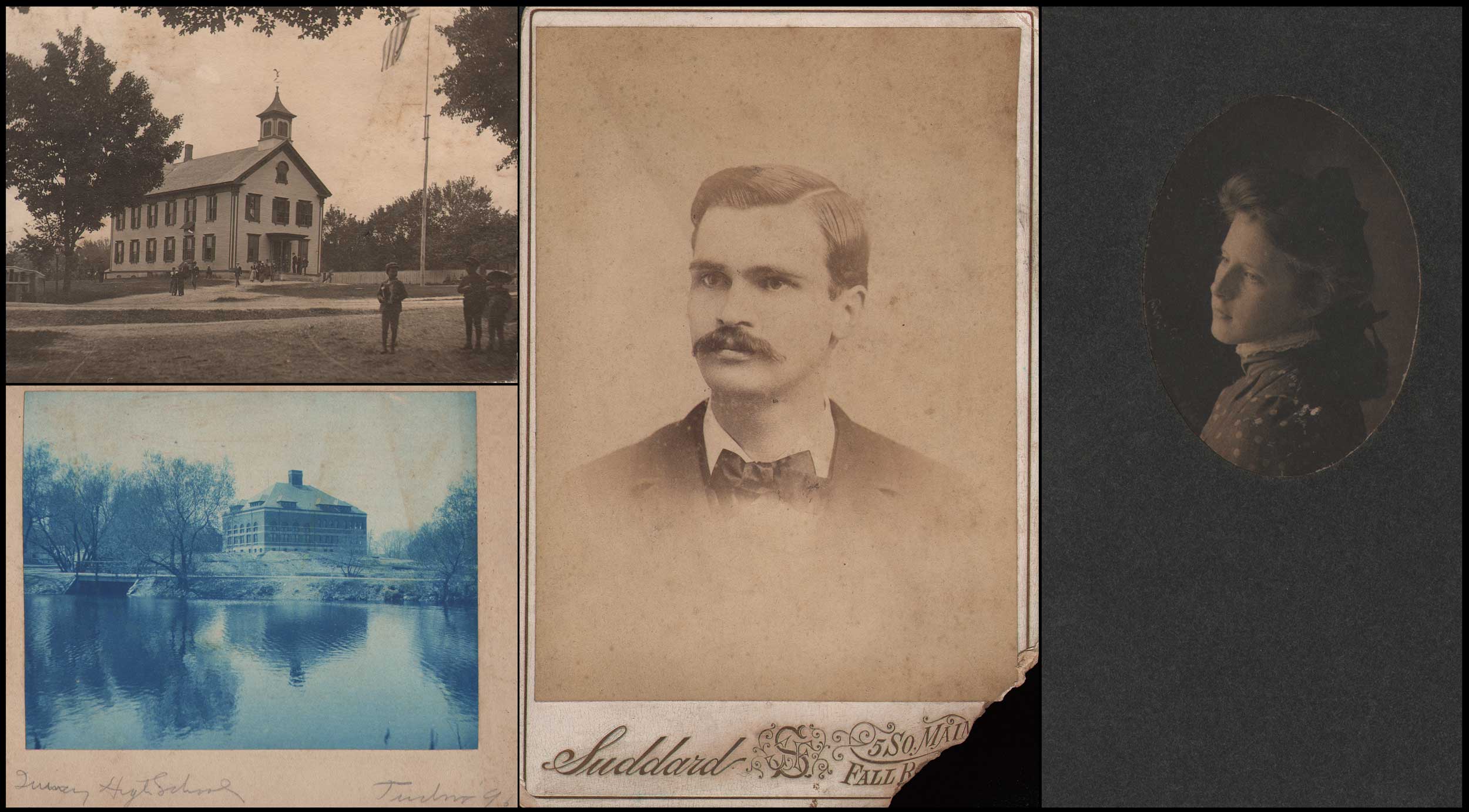

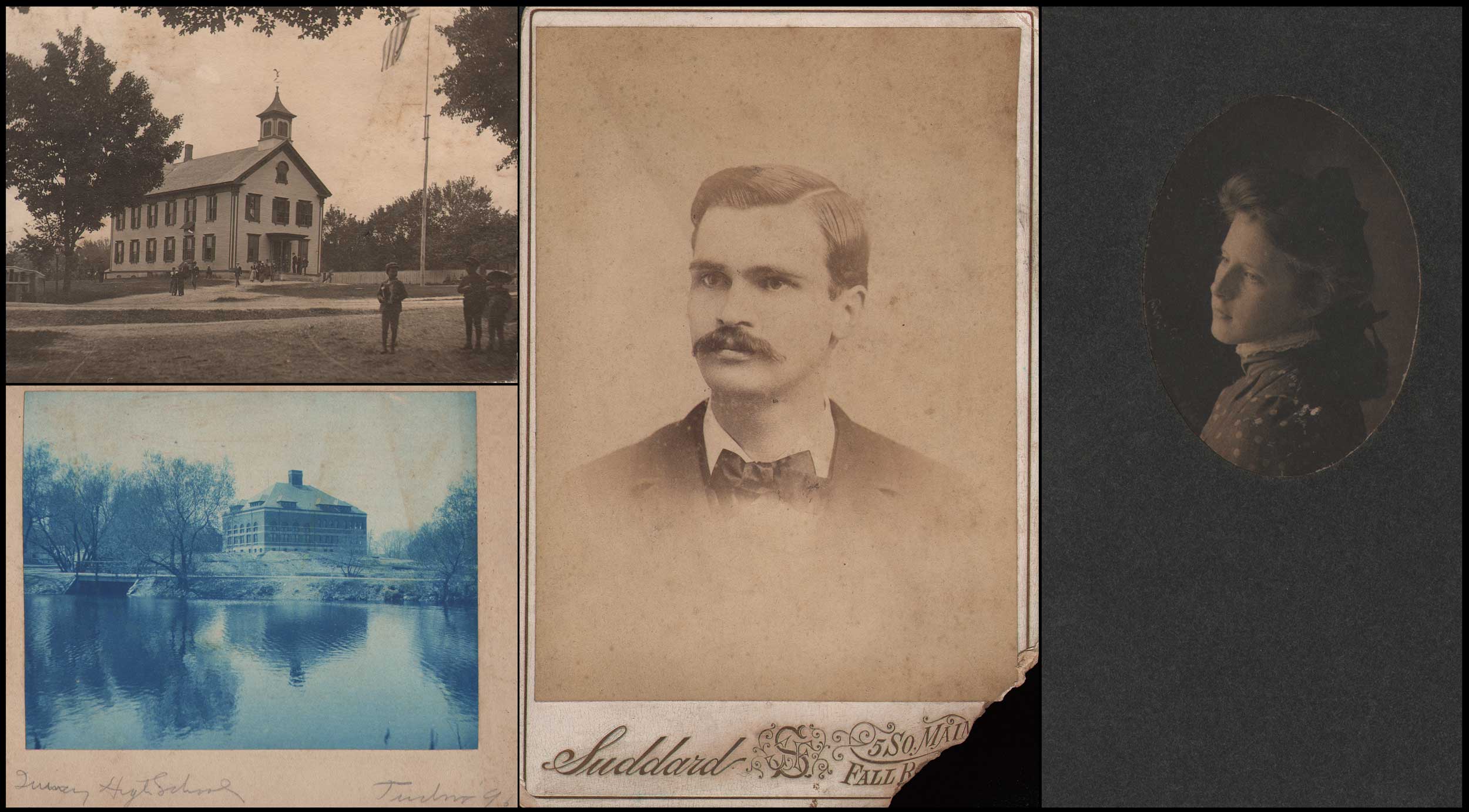

Early School Days: UL: “West Boylston High School”, ca. 1895, mounted gelatin silver print, 7.9 x 10.7 cm. LL: “Quincy High School” 1896, cyanotype print on cabinet card: 9.4 x 11.9 cm | 12.7 x 15.3 cm. Far Right: “Pratt Institute Girl”, ca. 1898-1900, mounted gelatin silver print, 6.9 x 5.0 | 18.1 x 13.1 cm. All: C.R. Tucker, American: 1868-1956. Center: “Cabinet Card of C.R. Tucker”, Studio of J.F. Suddard, Fall River, MA, ca. 1890-1895, mounted albumen print, 13.8 x 9.8 | 16.6 x 10.7 cm. Some of early school assignments for Tucker were as principal at West Boylston High School, submaster at Quincy High School and as an assistant instructor in physics at Pratt Institute, where this mounted student portrait was an early effort at photographing students. All: PhotoSeed Archive

These degrees and his love of people-especially children- would serve him well in a fruitful career as a teacher in public education for the next 45 years.

Through many fits and starts since acquiring the “C.R. Tucker Trove” of photographs, I’ve been able to piece together a truly fascinating life: a quintessentially American life at that- glued together by the love of his family and fueled by his own expansive, inquisitive mind.

Beginnings, Wanderings & Jumbo the Elephant

C.R. Tucker’s father George was a farmer and his mother Myra a homemaker. Although its assumed the Tucker family did not possess generational wealth based on the occupation of his father, pastures back then seemed greener in the American West, literally: especially for a farmer. With this in mind, when Charles was only four years old, he and his family traveled in a “prairie schooner”, better known as a covered wagon, in search of fortune to Missouri. That dream got detoured however, and the family pivoted north, to the state of Wisconsin. There, Charles found himself living in a log cabin for five years in the mid 1870s. Miraculously, a photograph of that log cabin survives to this day, and can be seen with this post. How many family’s in the 21st century can say their forebears grew up in a log cabin along with an actual picture to prove it?!

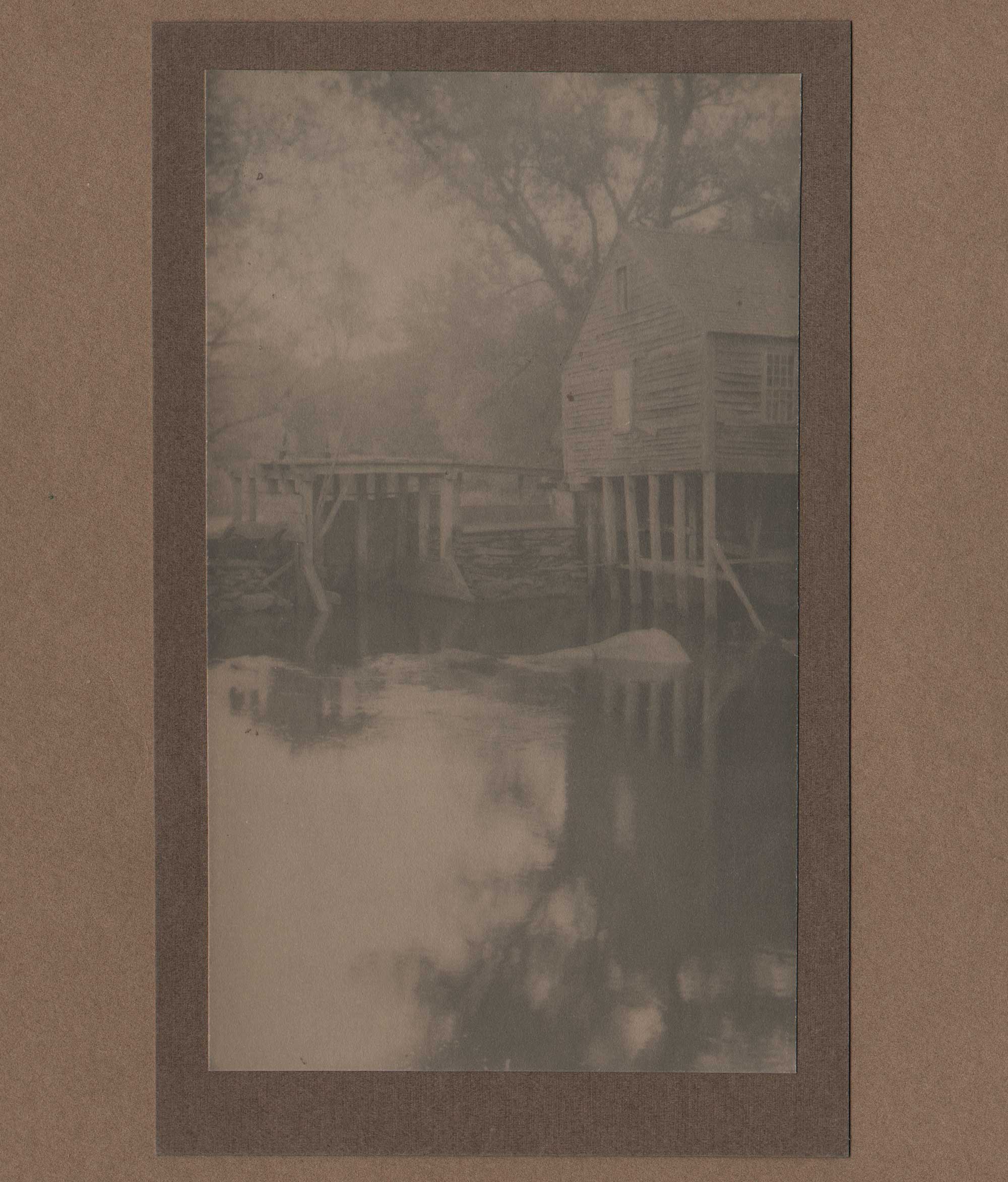

“Country Lane”, ca. 1905-1910: printed 1916, mounted bromide print, C.R. Tucker, American 1869-1956. 23.1 x 29.3 | 35.5 x 43.2 cm. Tucker enjoyed landscape photography, and this view of a dirt road with river or pond at left and buildings obscured in background may have been taken on Staten Island, N.Y., a locale where farms and open space were the norm versus the heavy populated landscape it is in the 21st Century. This mounted print is from a series of photographs bearing the artists signature and date 1916 at lower right corner that are believed to be from earlier negatives. The uniformity of the brown cardstock mounts indicates they were intended as exhibition prints. From: PhotoSeed Archive

Personal history obviously made quite an impression on Charles. In keeping with the idea of “home”, an early cabinet card believed taken by him in the late 1880’s, when he was still in high school or early in college, shows the oldest known American home- then or now- in existence: the Fairbanks House in Dedham, MA. Even then, as an impressionable newcomer to photography, he must have known of its significance, one worthy of his early efforts behind the camera. In contrast to his old childhood log cabin, the Fairbanks house, dating to 1641, is the oldest surviving timber-frame house in North America.

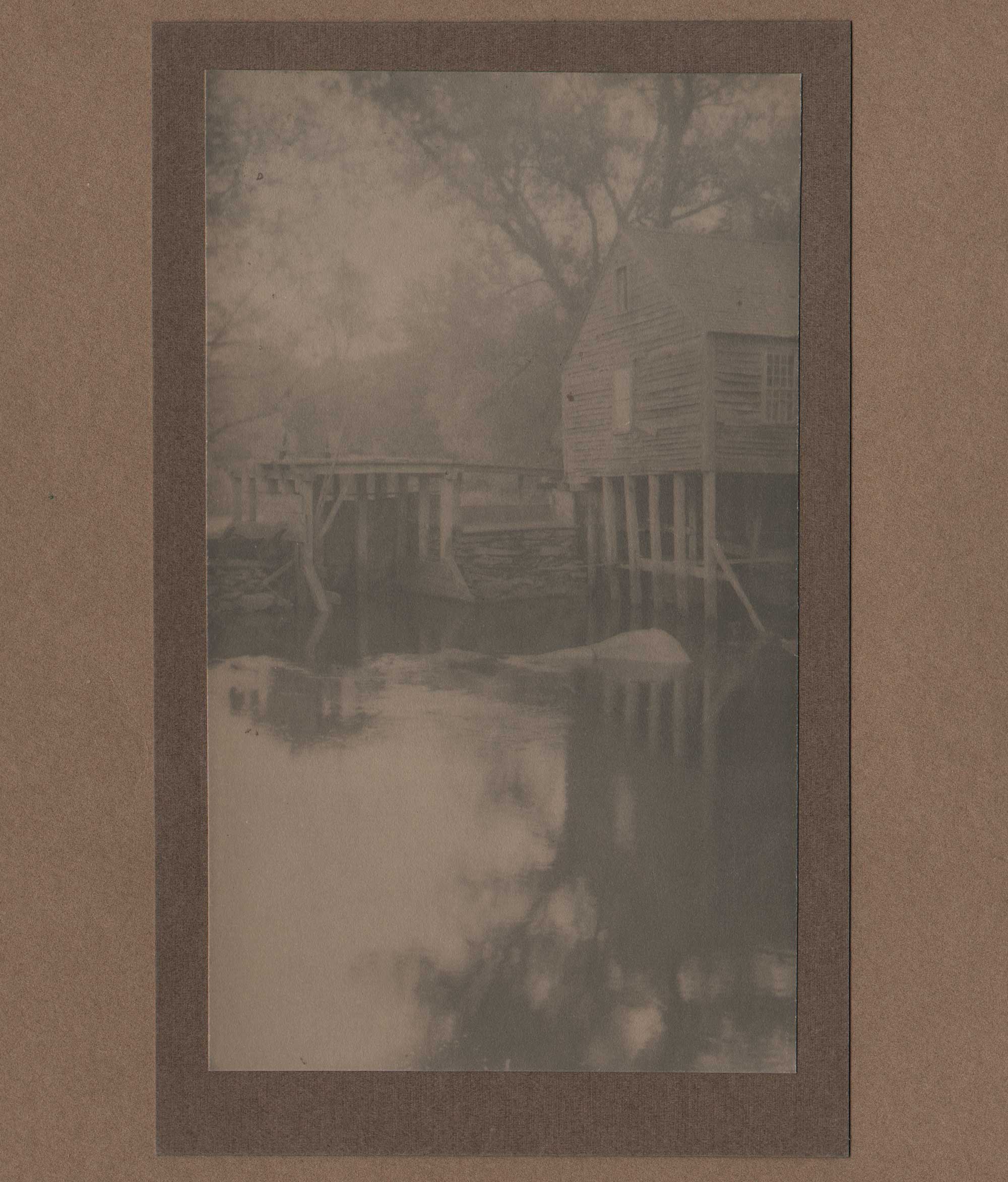

“The Old Mill”, ca. 1906, mounted platinum print, C.R. Tucker, American 1869-1956. 16.4 x 9.7 | 18.6 x 11.4 | 29.3 x 22.9 cm. This is a variant, with orientation reversed, of a bucolic waterscape study titled “The Mill” by the artist & published in the June, 1906 issue of the Photo-Era. At the time, Tucker was a member of The Postal Photographic Club of the United States. The location of the photo is the Old Mill on Crescent Street in West Bridgewater, MA. A later photograph of this mill, now believed lost and taken around 1915 can be seen here. From: PhotoSeed Archive

In the Spring of his sophomore year at Tufts, April, 3, 1889, an opportunity featuring a different kind of home crossed paths with Tucker’s amateur photography skills. This took the form of the the newly built Barnum Museum of Natural History on campus. For the future secretary of the brand new Tufts Camera Club, Charles Tucker got to record history in photographing a unique specimen of the circus impresario Barnum: his former colossus, the now stuffed Jumbo the Elephant. Mounted on a platform before being moved and placed on exhibit inside the new museum, Several of Tucker’s photographs, including the one with this post, were quickly turned into crude woodcuts: used to illustrate an article written by Tufts graduate and Boston Daily Globe reporter Julien C. Edgerly for the April 4, 1889 edition. In March, 2015, I used this original brown-toned, gelatin silver print of Jumbo mounted as a cabinet card to illustrate a news story on how Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus was going to retire their performing pachyderms. Alas, other than a small photo not held by this archive of the artist’s dorm room, no other currently identified photographs taken by the college student-in the capacity of his camera club membership or otherwise- are known to survive.

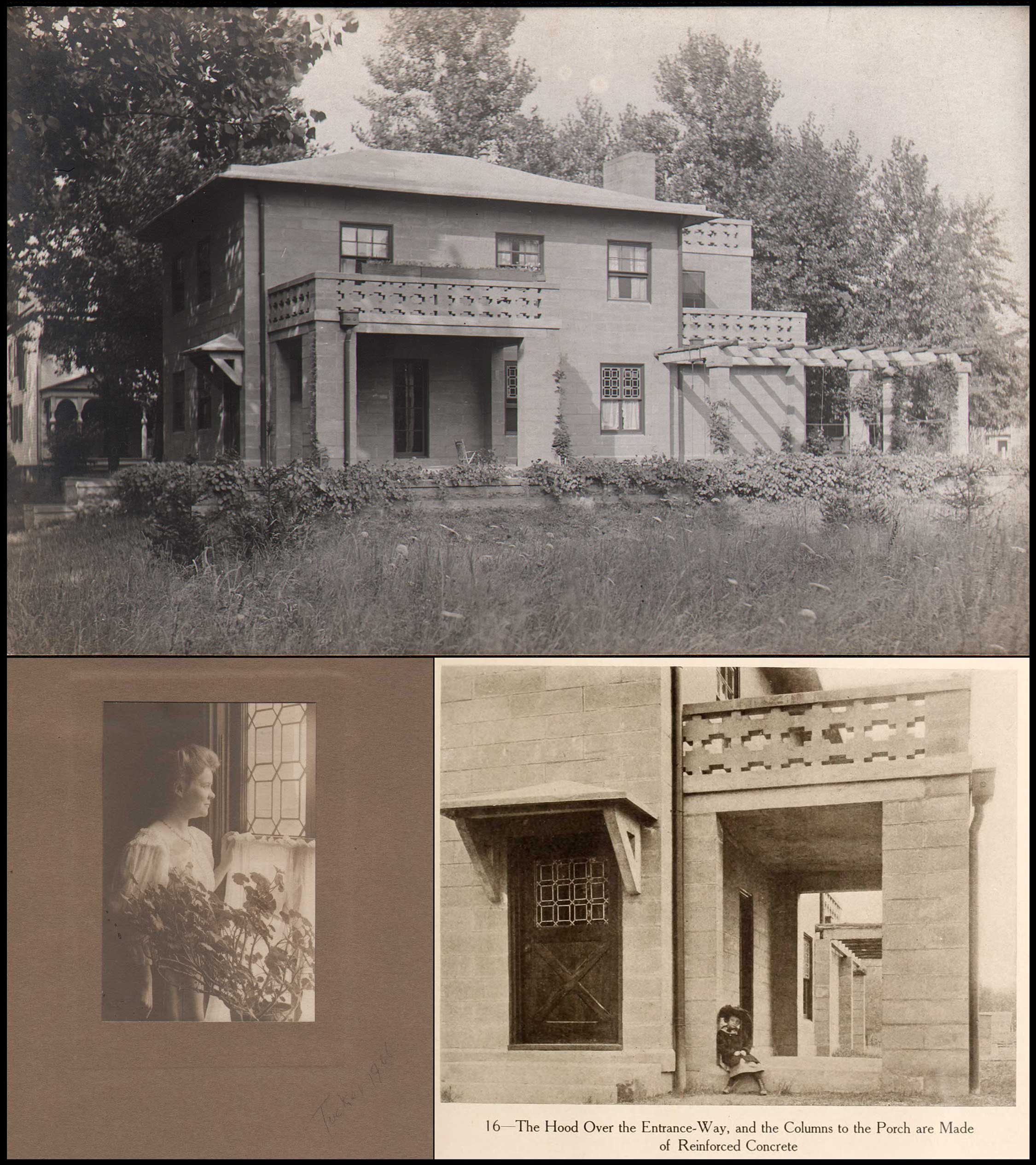

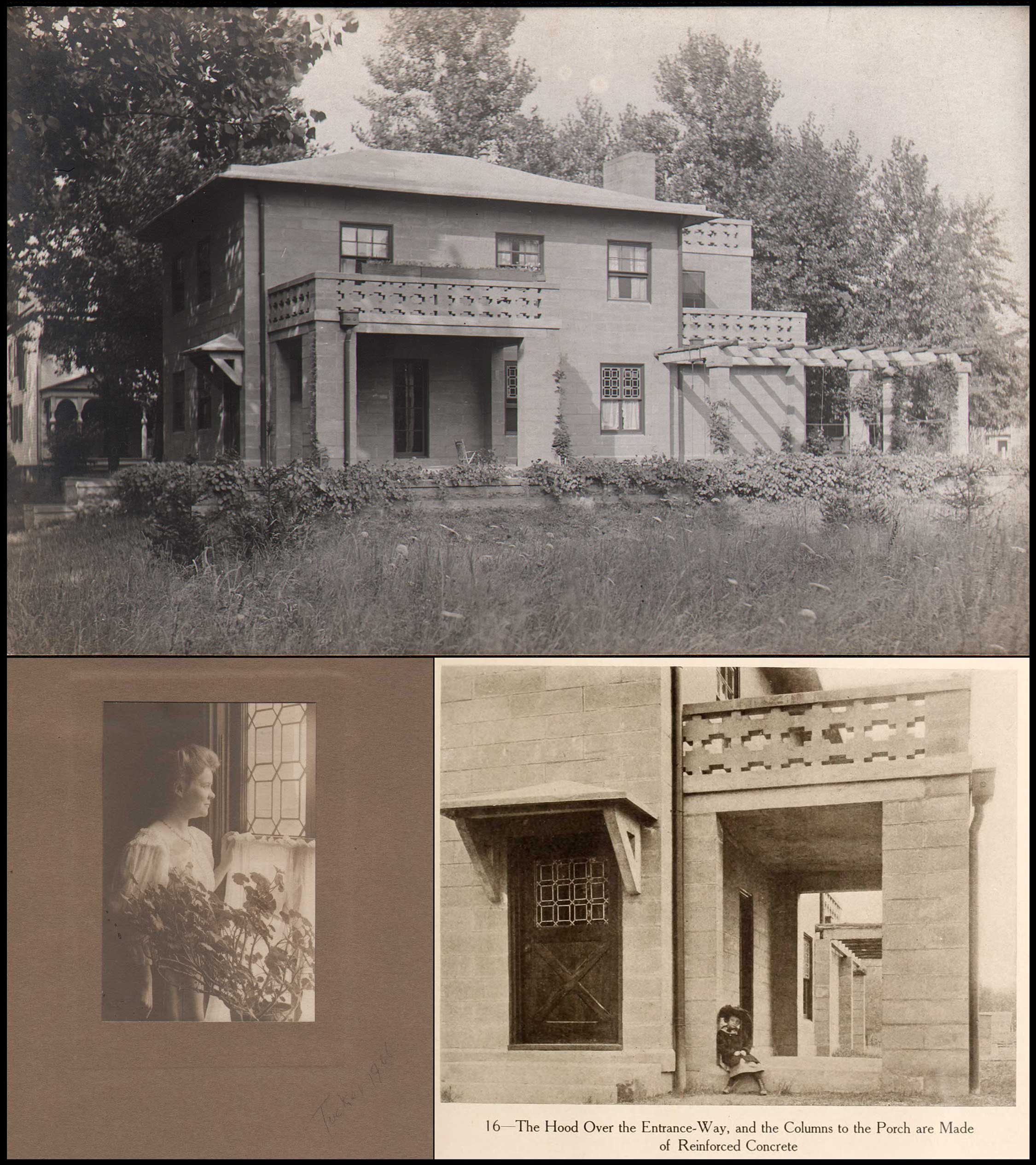

Top: First home owned by Tucker Family: “90 Third St. New Dorp, Staten Island”, ca. 1910, probably C.R. Tucker, American, 1868-1956, unmailed, divided back CYKO gelatin silver rppc, 8.6 x 13.7 cm, from: PhotoSeed Archive. LL: “The Window”, 1906, mounted platinum print, C.R. Tucker, American, 1868-1956, 9.9 x 6.6 | 31.4 x 16.5 cm. From: PhotoSeed Archive. LR: “Dorothy Tucker seated on Veranda”, 1906, halftone published as illustration: “Some Modern Concrete Country Houses” in August, 1906 American Homes and Gardens magazine. The artist’s wife, Mary Carruthers Tucker, peers out the first floor dining room window the same year the family moved in, the concrete home’s second owners. Built ca. 1904-05, the revolutionary structure, now demolished, was designed by important American architect Robert Waterman Gardner, who pioneered reinforced concrete in residential construction.

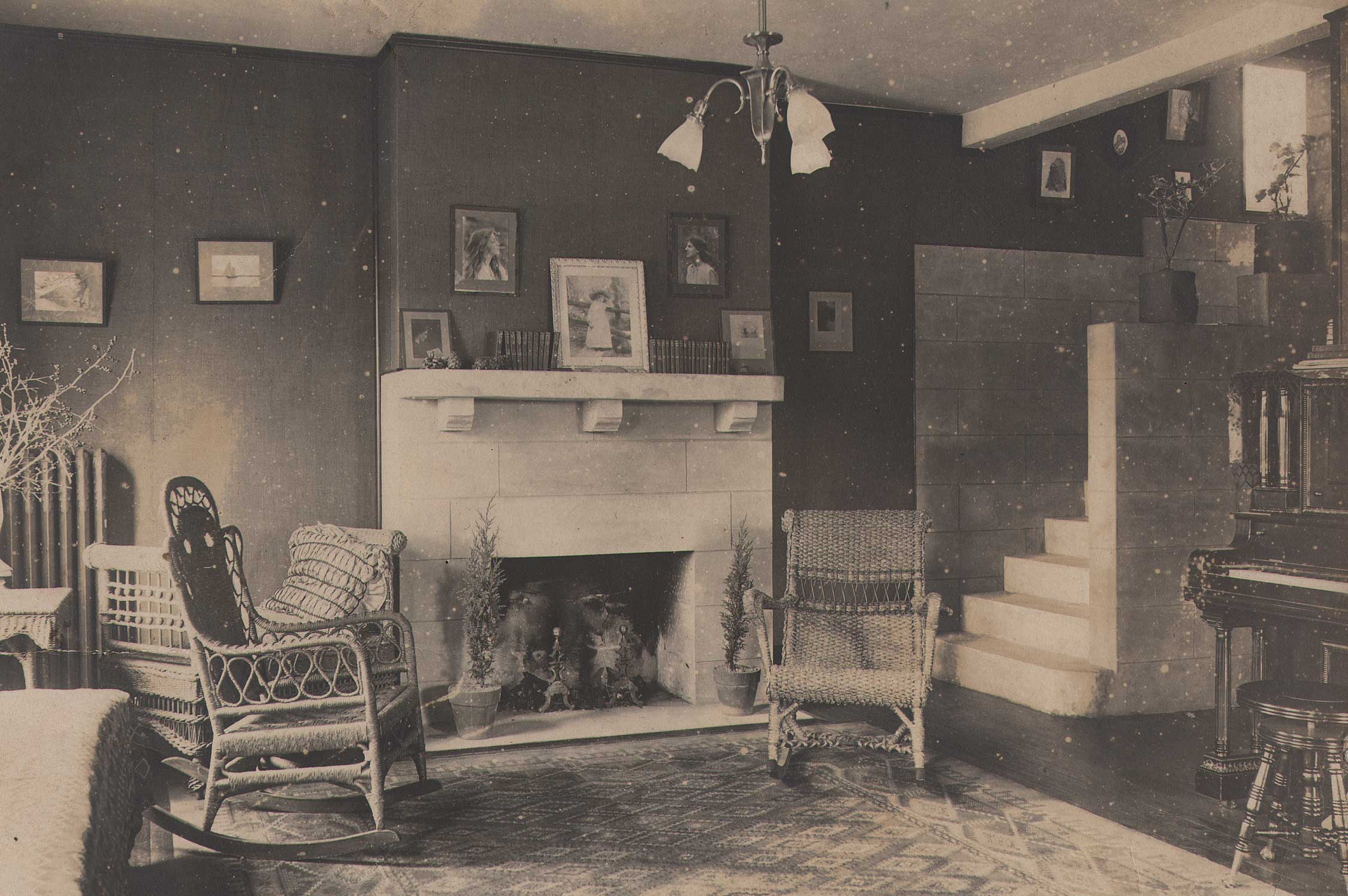

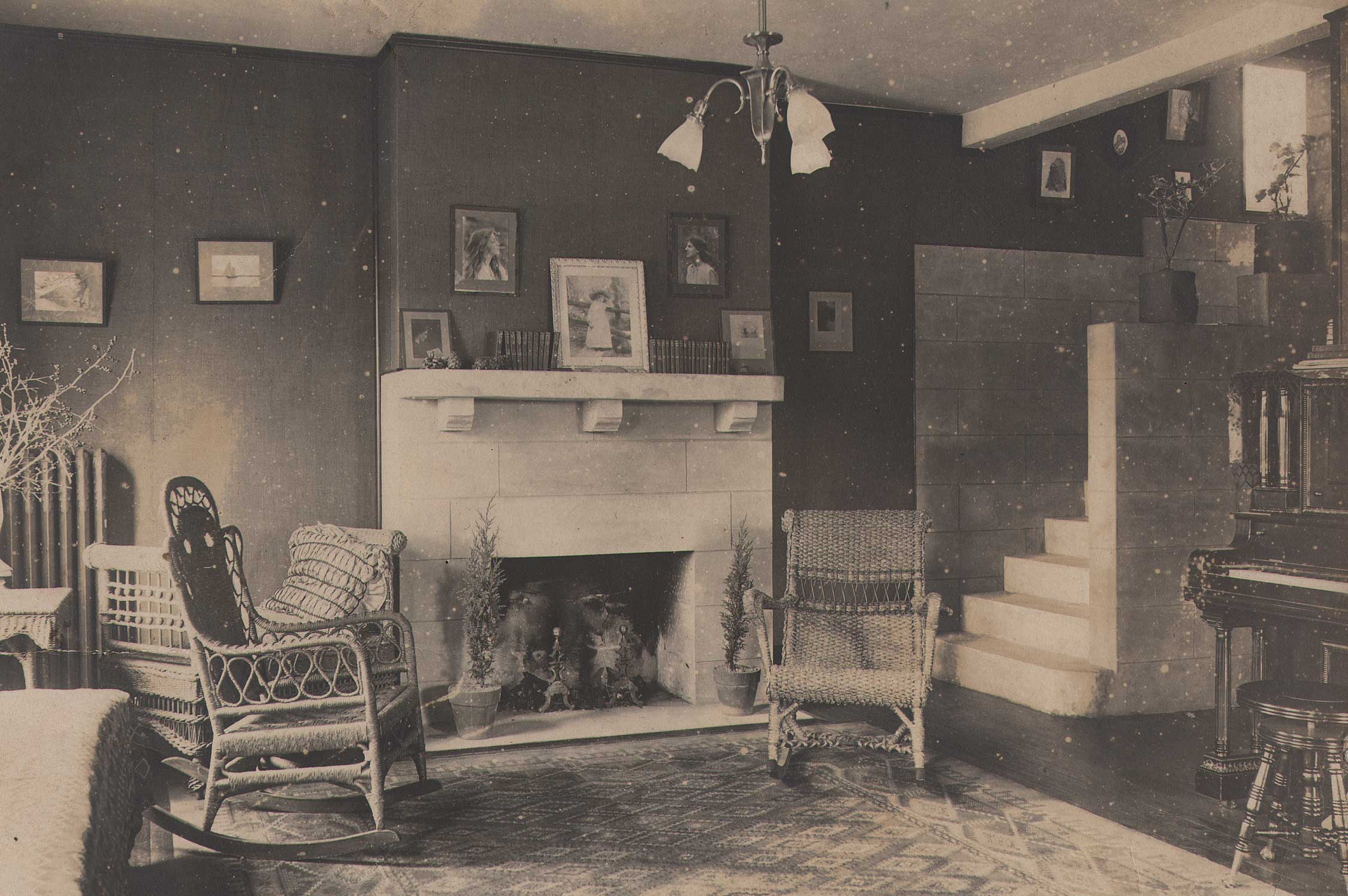

The artist’s work adorns the walls: “Living Room: 90 Third St. New Dorp, Staten Island”, ca. 1906-10, unmounted gelatin silver print, shown slightly cropped, C.R. Tucker, American, 1868-1956, 20.0 x 20.0 cm. This interior study shows the decorated Tucker family living room of their revolutionary concrete home. Photographs by the artist are on far wall, including original prints now held by this archive. Far left: “Cathedral Ledge and Echo Lake, North Conway, NH”; center, perched on fireplace mantle: framed photo of artist’s daughter Dorothy; either side of this on wall: framed profile portraits of Curtis High School students; far right, perched on mantle: “At Point O’ Woods Long Island”, from 1899. From: PhotoSeed Archive

But what of another future home, this time for the family residence of an older C.R. Tucker? A futuristic one of course, the perfect manifestation for someone who then made his living as a high school physics teacher. A revolutionary structure built ca. 1904-05, this abode was built entirely of concrete, owned by Tucker and his wife Mary as its second owners when purchased with the aid of a mortgage in 1906.

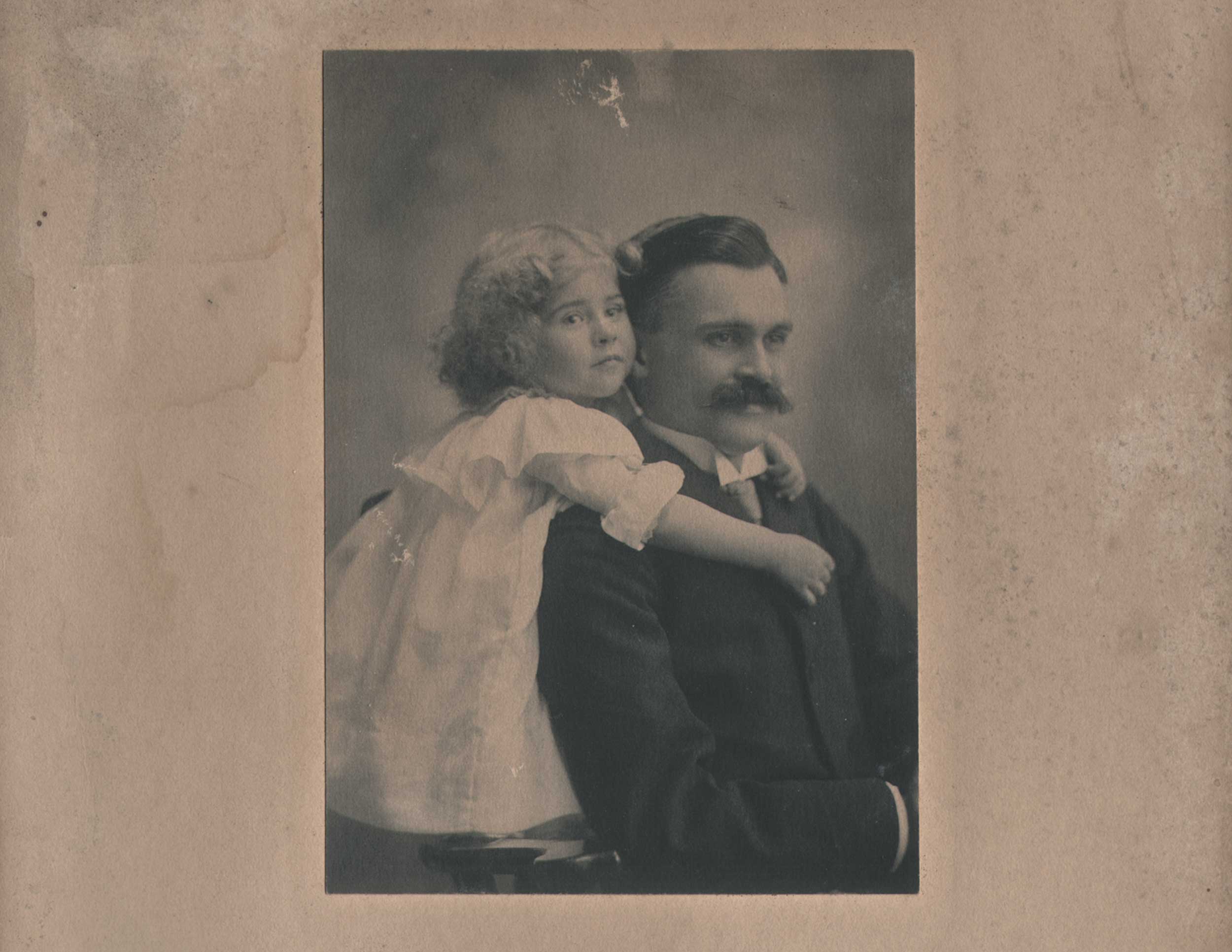

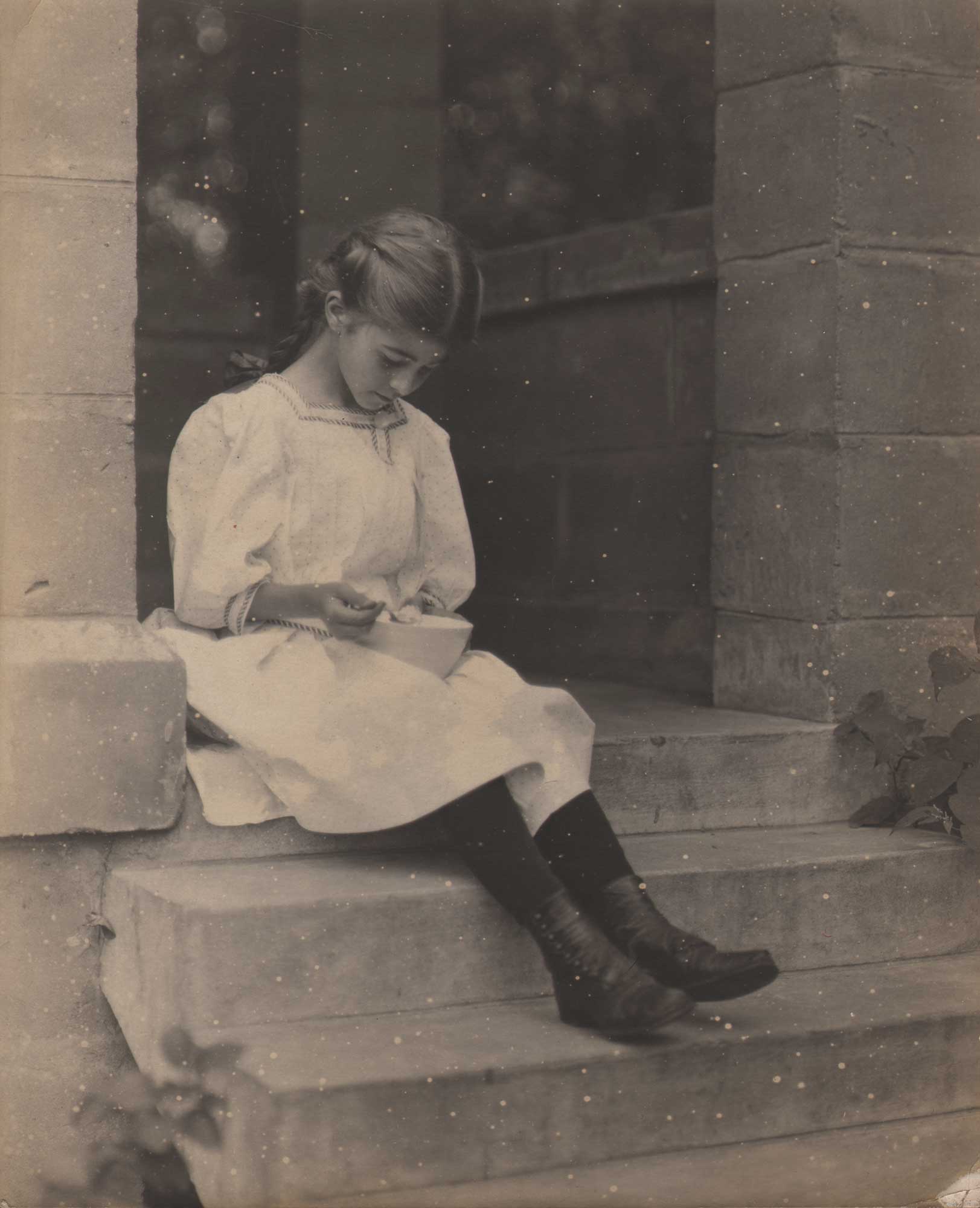

Designed by the important American architect Robert Waterman Gardner, who pioneered using reinforced concrete in residential construction, the home brought me down more than one rabbit hole in my research. Recently, with the evidence of several interior photographs of the home I purchased included with the Tucker “trove”, a wonderful discovery was made. This was an August, 1906 article (begins: p. 88) showcasing the residence in American Homes and Gardens magazine. Delightfully, who would show up in several of the uncredited halftone photographs published with this article? Tucker’s daughter Dorothy, a little over six years old, sitting by herself, unidentified, perched on the edge of the ground level veranda.

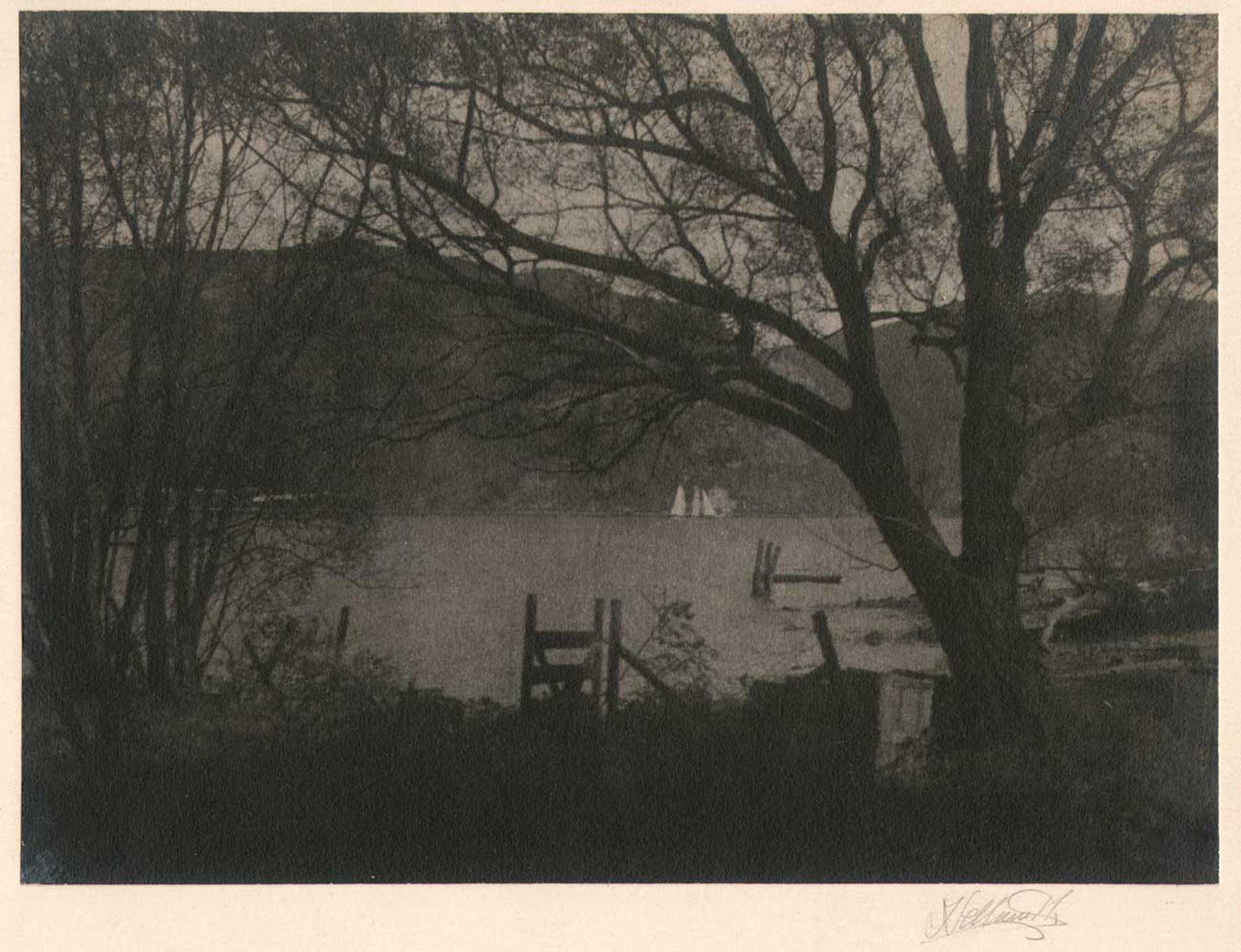

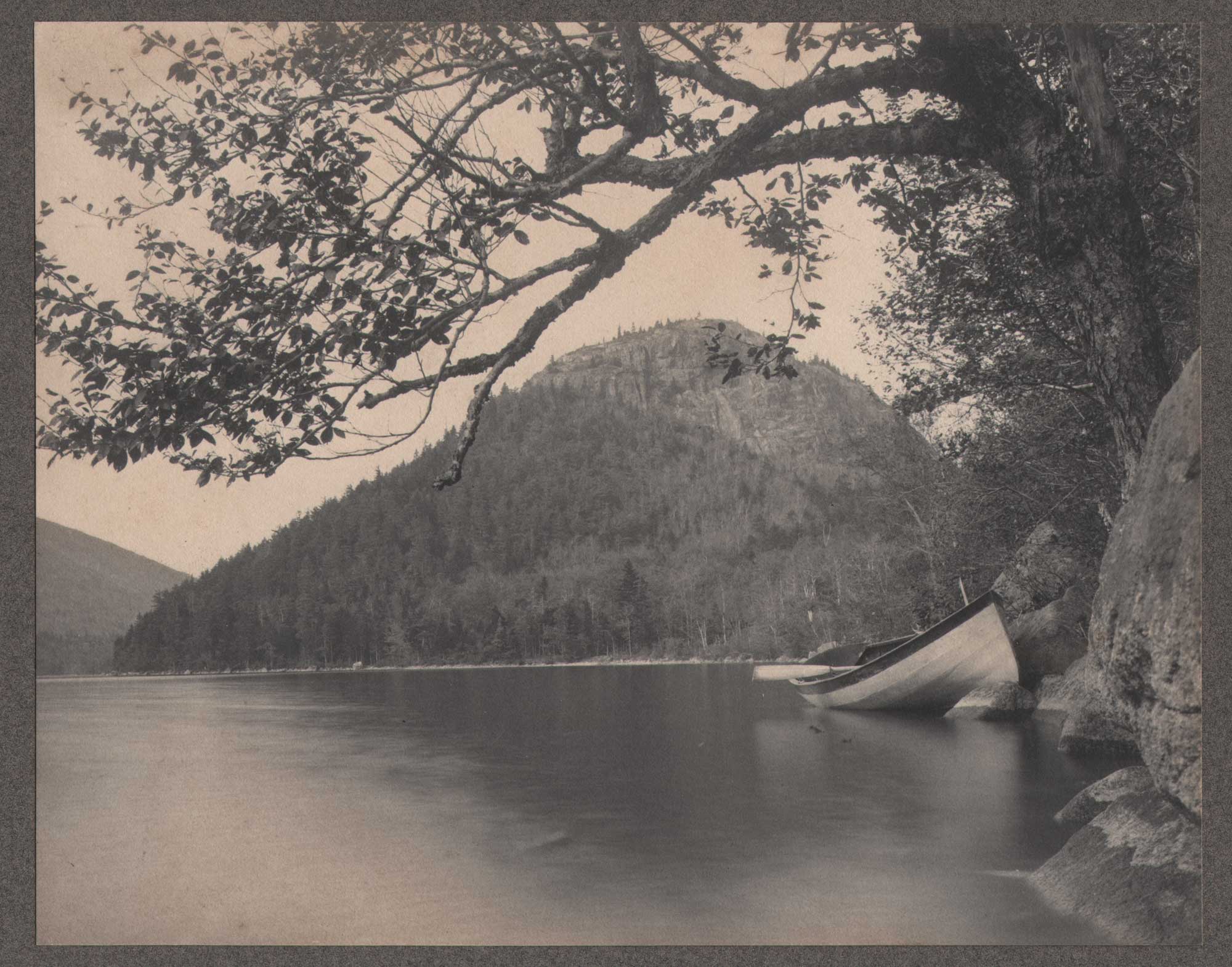

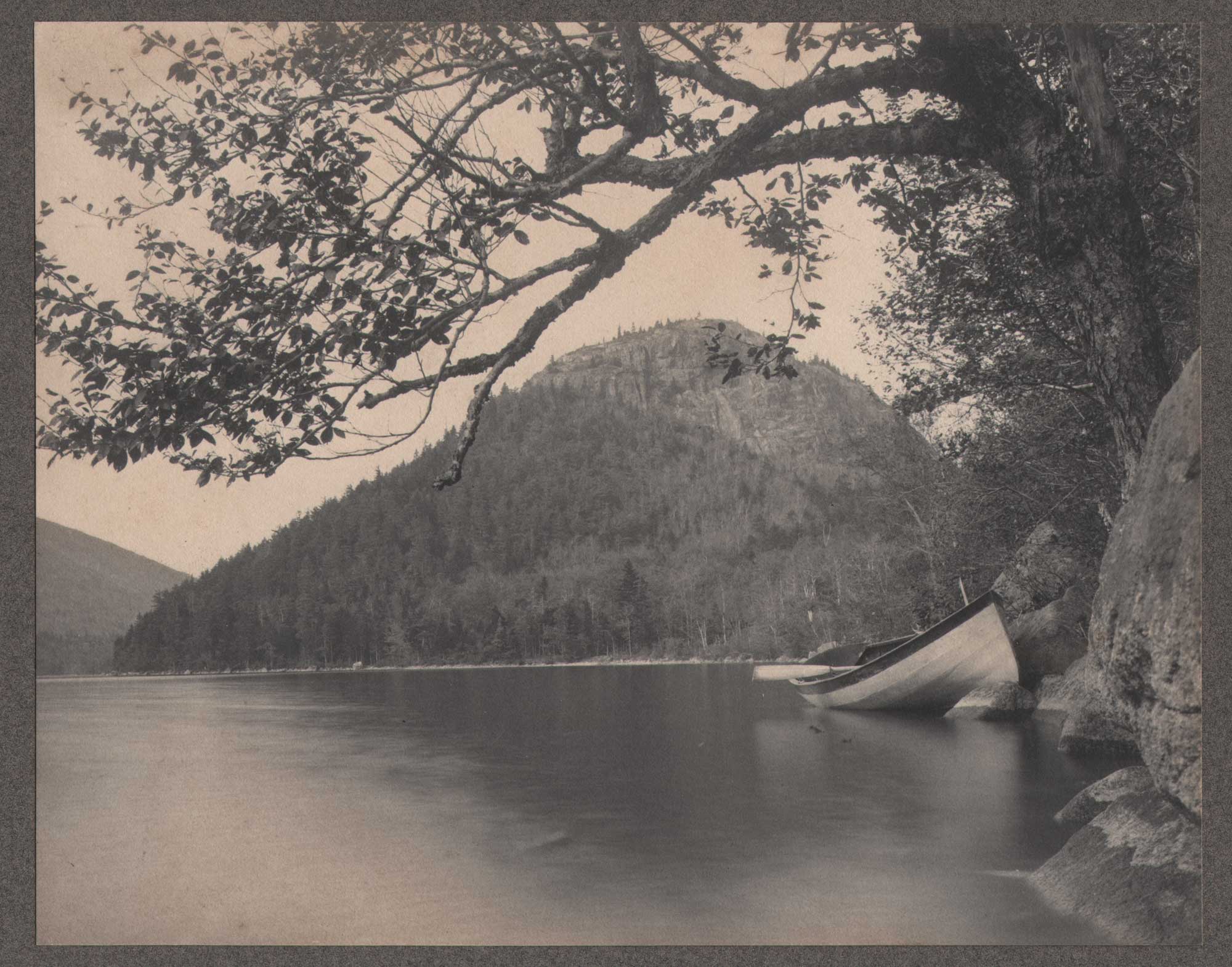

“Cathedral Ledge and Echo Lake, North Conway, NH”, ca. 1900-05, tipped platinum print to card mount, C.R. Tucker, American, 1868-1956, 15.2 x 19.1 | 25.3 x 30.4 cm. A large rowboat with protruding oar frames this serene lakeside study. This archive is fairly confident the view shows the rock outcropping of Cathedral Ledge overlooking Echo Lake in New Hampshire. A framed example, perhaps this print, hung on the dining room wall of the artist’s concrete Staten Island home- seen in previous photo above. From: PhotoSeed Archive

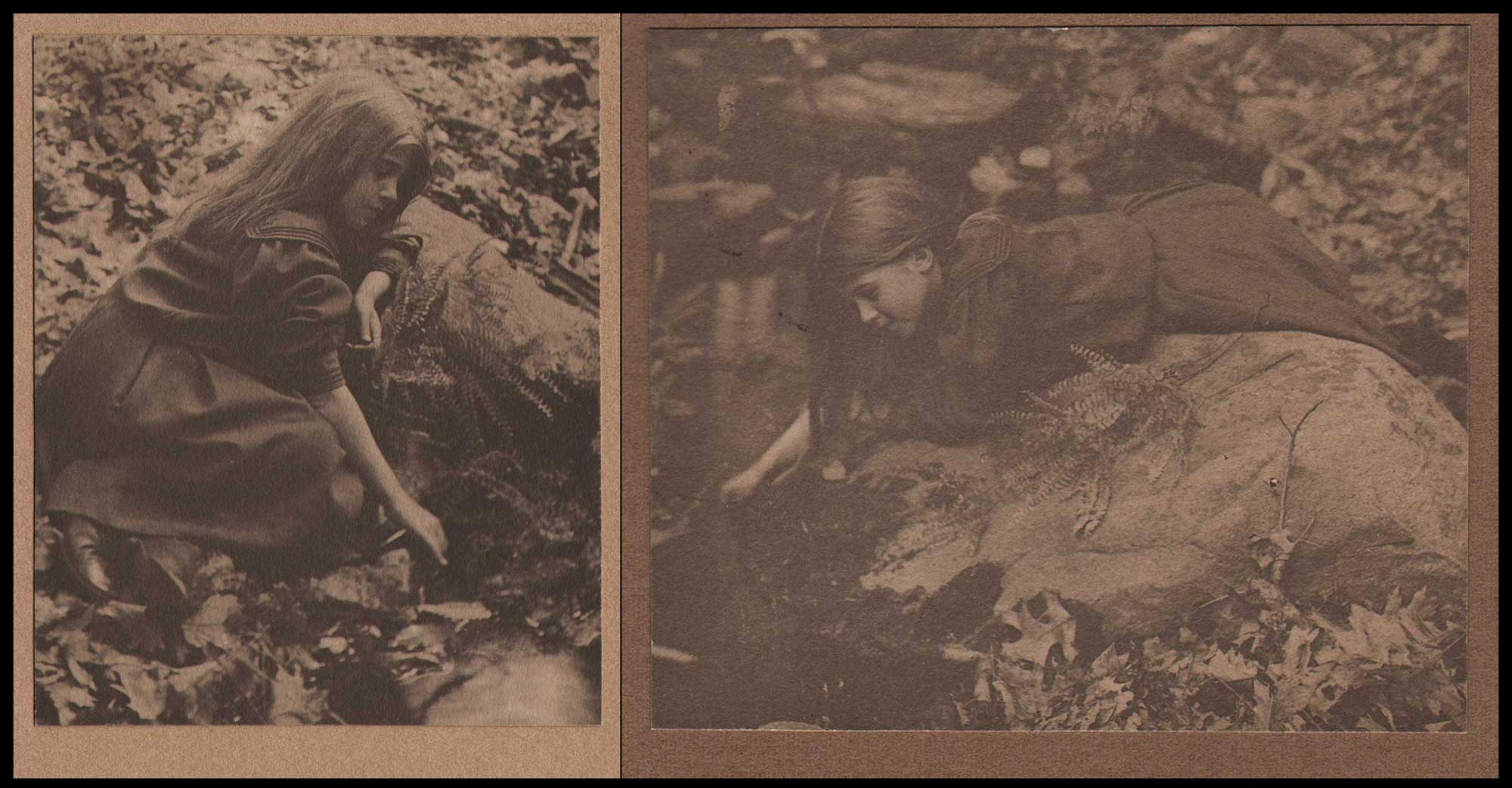

Left: “Curtis High School Girl”; Right: “Girl with Braids”, both ca. 1905-1910: printed 1916, mounted bromide prints, C.R. Tucker, American 1869-1956. Left: 27.2 x 21.3 | 43.2 x 35.5 cm, Right: 26.7 x 17.6 | 43.2 x 28.4 cm. These prints are from a series of photographs bearing the artists signature and date 1916 at lower right corner, and are believed to be from earlier negatives. The uniformity of the brown cardstock mounts indicates they were intended as exhibition prints. Another extant unmounted print of “Curtis High School Girl” seen here includes the name Eloise Poulin (?) crossed out-perhaps the name of the subject. This particular portrait was displayed with others over the fireplace mantle of the artist’s New Dorp home: From: PhotoSeed Archive

Located in the New Dorp area of Staten Island, N.Y. but unfortunately now demolished, the magazine lay claim at the time of publication that it was “the first building of this character to be constructed in New York City.” Historians of early concrete homes will find new things to ponder, and the article and published floor plans gave me further insight into the location and backdrop for many of the Dorothy and Tucker family photographs included in the larger archive.

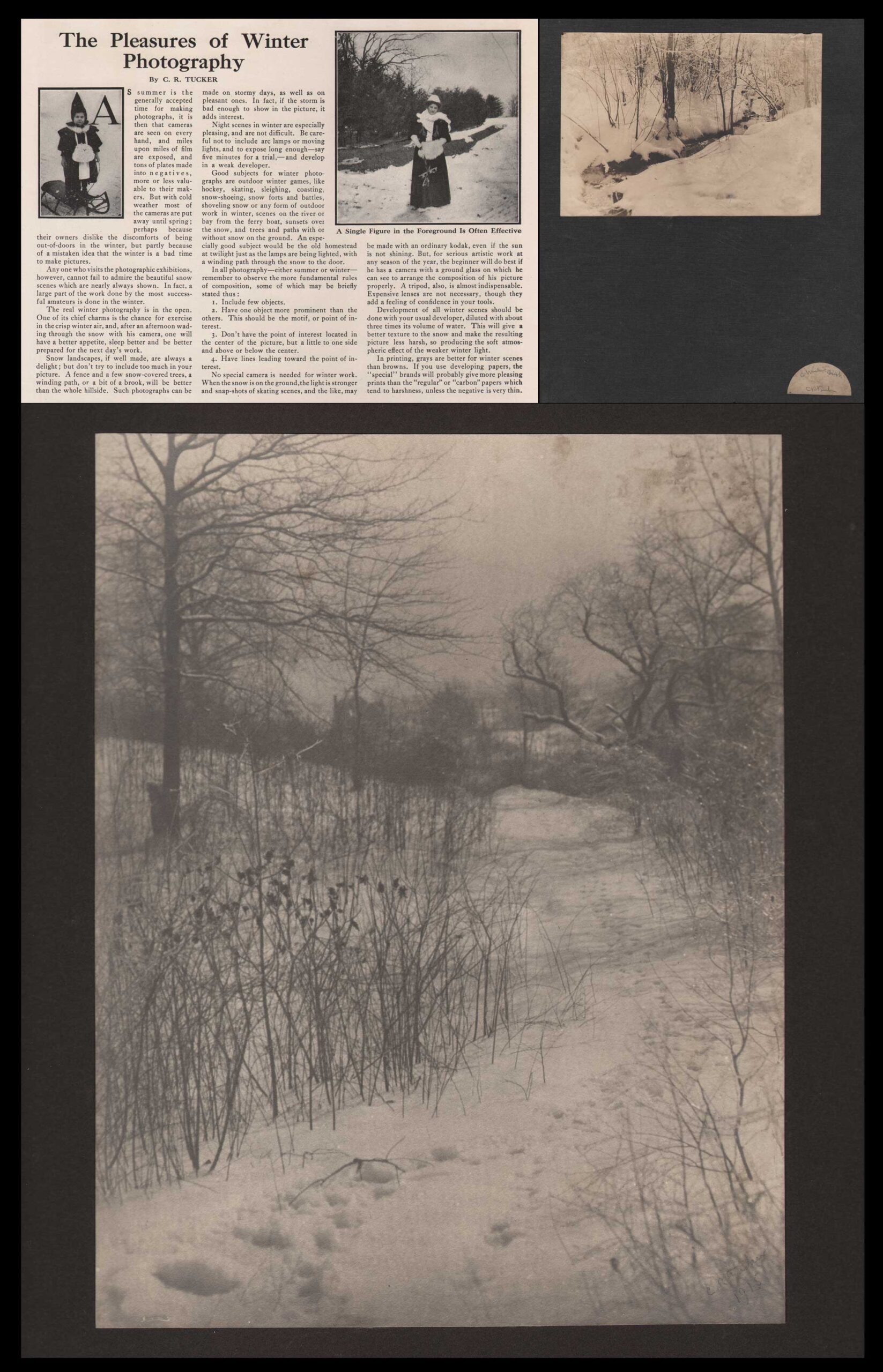

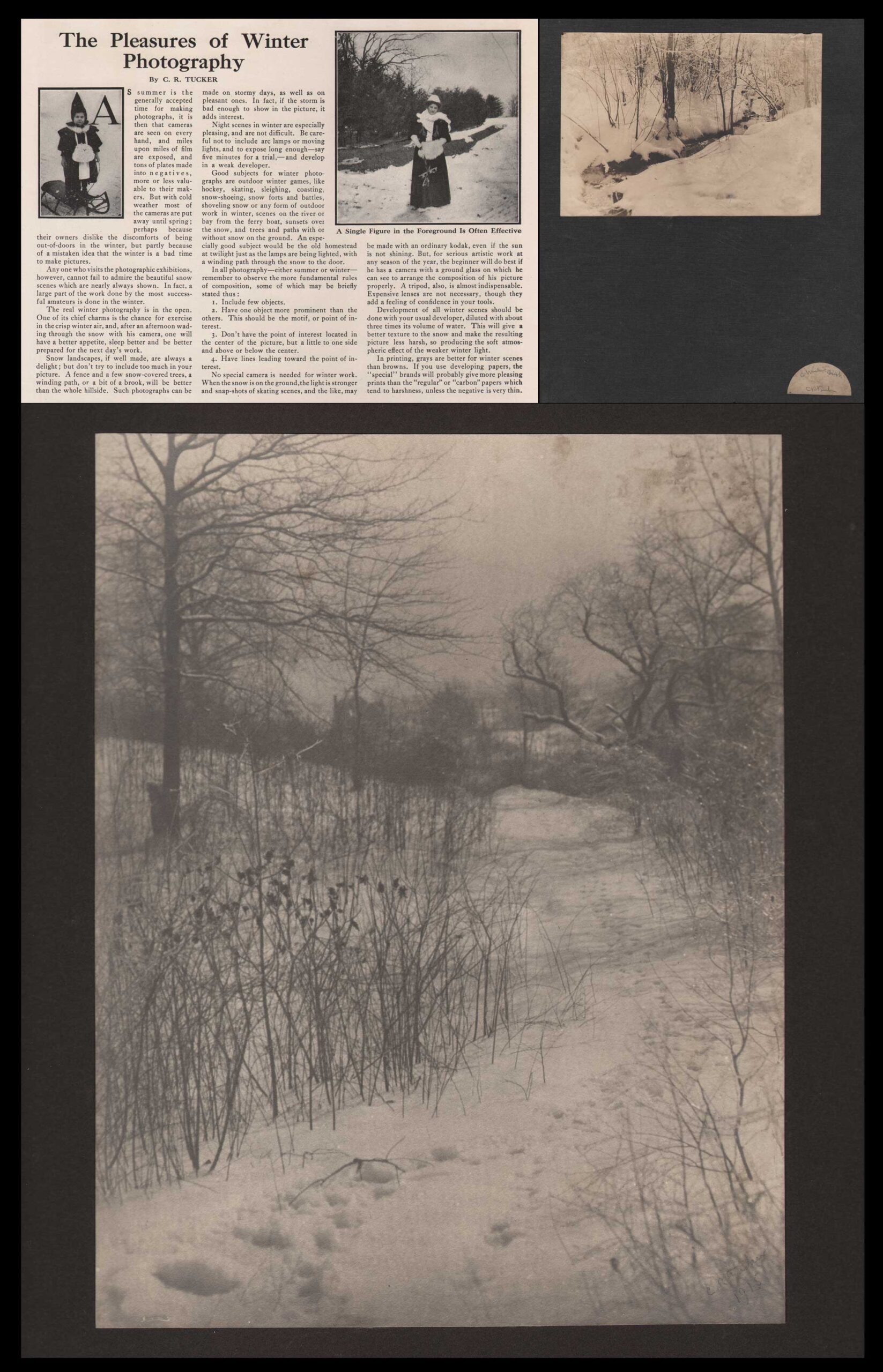

Author and Practitioner: Left: “The Pleasures of Winter Photography by C.R. Tucker”, in: Suburban Life, December, 1907. Excerpt: from first page of article: “Snow landscapes, if well made, are always a delight; but don’t try to include too much in your picture. A fence and a few snow-covered trees, a winding path, or a bit of a brook, will be better than the whole hillside.” Two halftones, believed to show the photographer’s daughter at left and wife Mary, are shown. The four-page spread included at least one other photo by the author. Examples of the aforementioned brook and path: Right: “A Winter Brook”, Bottom: “Snowy Path”, both ca. 1905-10, C.R. Tucker, American 1869-1956. Brook: mounted POP print: 11.8 x 16.8 | 31.0 x 24.5 cm; Path- signed and dated 1915: mounted bromide print, 29.5 x 22.9 | 43.2 x 35.5 cm. From: PhotoSeed Archive

A Public School Teaching Career Informed from the Age of 10

There he matriculated in an old red school house – Seems to have garnered a good deal out of it, too- 1949

…but wherever Charles Tucker is his heart and his camera capture children. Wherever he is he is the sun to which the children, like sunflowers, turn. -The Alden Letter, 1950

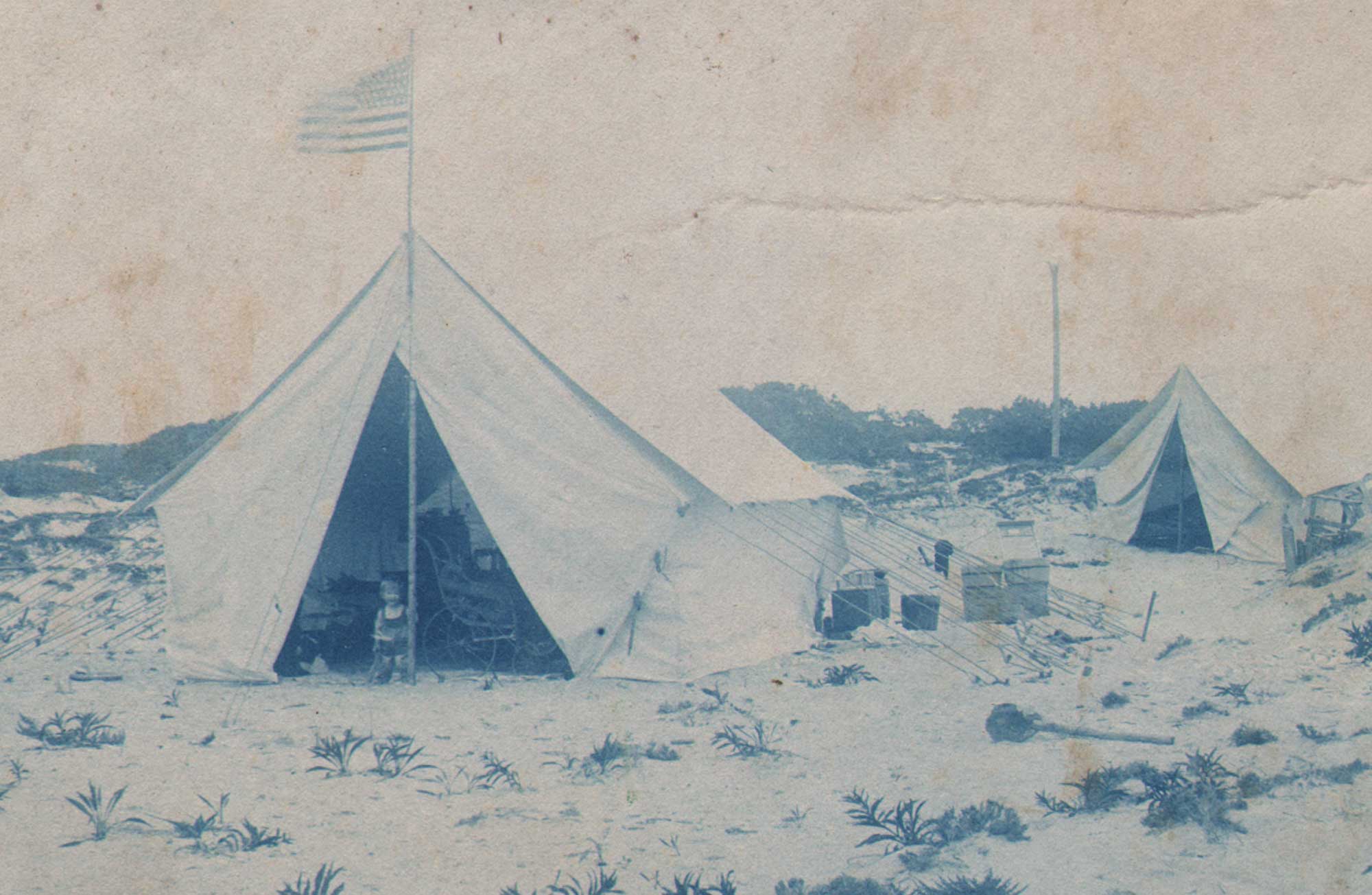

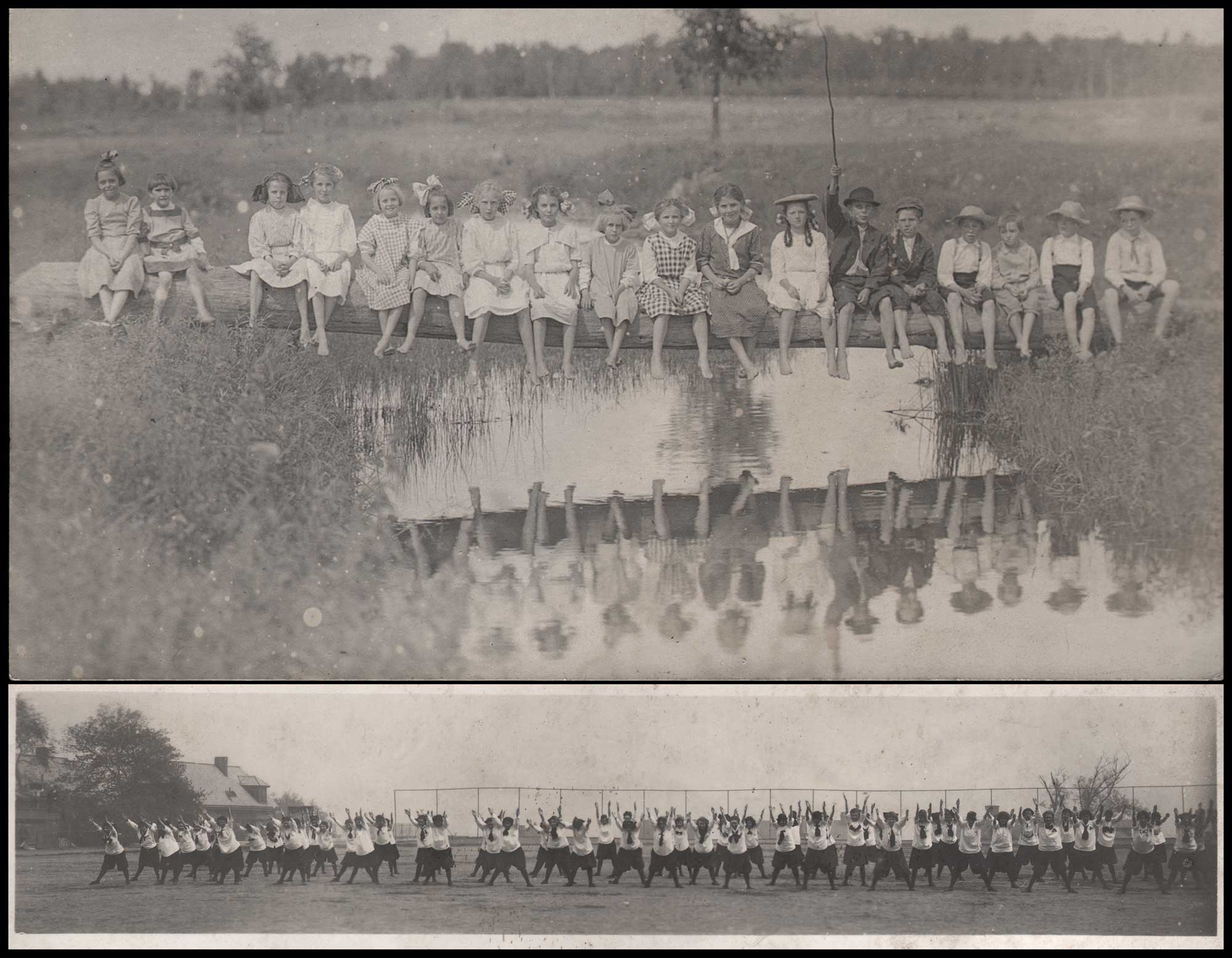

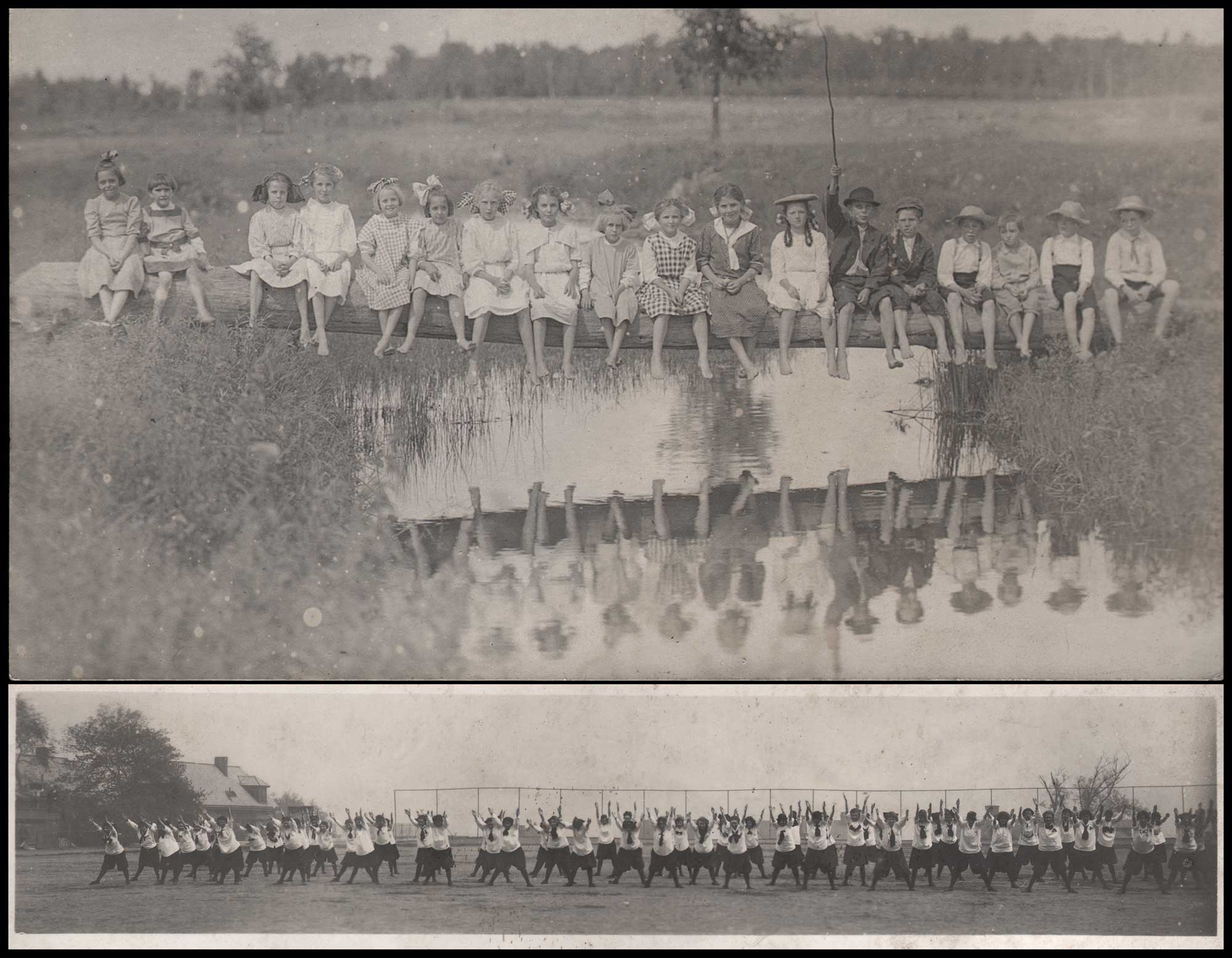

Children & Students- a Favorite Subject: Top: detail: “Sunday School Picnic, Spencer Wisconsin”, 1908, Bottom: “Young Women Exercise at Curtis High School”, ca. 1910, both: unmounted gelatin silver prints, C.R. Tucker, American 1869-1956. Top: 9.8 x 14.0 cm, Bottom: 5.0 x 25.2 | 7.4 x 33.2 cm, Top: water reflections of a group of Sunday school students lined up on a log give this photo an extra dimension: the photographer and his wife traveled to WI during summer months to visit relatives. Bottom: Curtis students wearing “romper” style gym outfits exercise on a field at the Staten Island school. “Bloomers”, “Middy” blouses and loose scarves made up the uniforms. Both: PhotoSeed Archive

Principal of Procter Academy, Provo, Utah, for one year; Principal of West Boylston, MA, High School; Submaster in Quincy, MA High School; Working in the Educational Department at the YMCA (Springfield, MA Training School); Assistant instructor in physics at Pratt Institute, Brooklyn, N.Y.; Physics teacher at Stapleton High School in New Brighton on Staten Island; Physics teacher at the brand-new Curtis High School on Staten Island; long-time professor of physics at Manual Training High School in Brooklyn, N.Y. These teaching assignments made up the bulk of C.R. Tucker’s 45-year public teaching career, and could be looked on as a testament to his being a pragmatist in what surely were the fickle ministrations over the decades of an ever changing series of administrations. But what can be assumed through it all, as evidenced by the above 1950 quote, is that the children and young adults he taught made it all worthwhile for him.

Female Studies: Left: “A Head”, 16.8 x 13.1 cm | 33.2 x 25.5 cm, Right: “Curtis High School Girl”, 18.2 x 21.2 cm, 1909 at left; ca. 1905-10 at right, mounted and unmounted platinum prints, C.R. Tucker, American 1869-1956. The profile portrait at left of an unknown, older female subject retains a portion of its original Postal Camera Club label on verso, indicating author, title and sequence- #1, for August, 1909 club’s portfolio. Right: This pleasing study of an unknown young woman resting before a lake is a warm brown platinum print: the photographer additionally printed it as a bromide print in 1916, probably for exhibition. Both: PhotoSeed Archive

Reportedly warm in personality: a proven public speaker with the capacity for humor in telling a good story, he cuts a dashing figure in surviving photographs. Wearing an ever-present silk cravat but with the contradiction of tousled hair in throwing off the look in several surviving photographs, Tucker at the end of the day was a realist. To wit, in his 1956 obituary, his good friend E. Huling Woodworth, the deputy governor general of the General Society of Mayflower Descendants, quoted Tucker that he went to New York City in the promotion of his teaching career: “simply because they paid me more money”. Around 1920, the amateur photographer seemed to have had enough however. Looking back much later in life, he said: “I tried teaching for 45 years; decided I couldn’t do it, and when they told me they would rather pay me than have me around, I bought a Vermont farm, but I kept on teaching, to try to pay farm expenses; I am now living on the interest of what I lost, trying to be a farmer”.

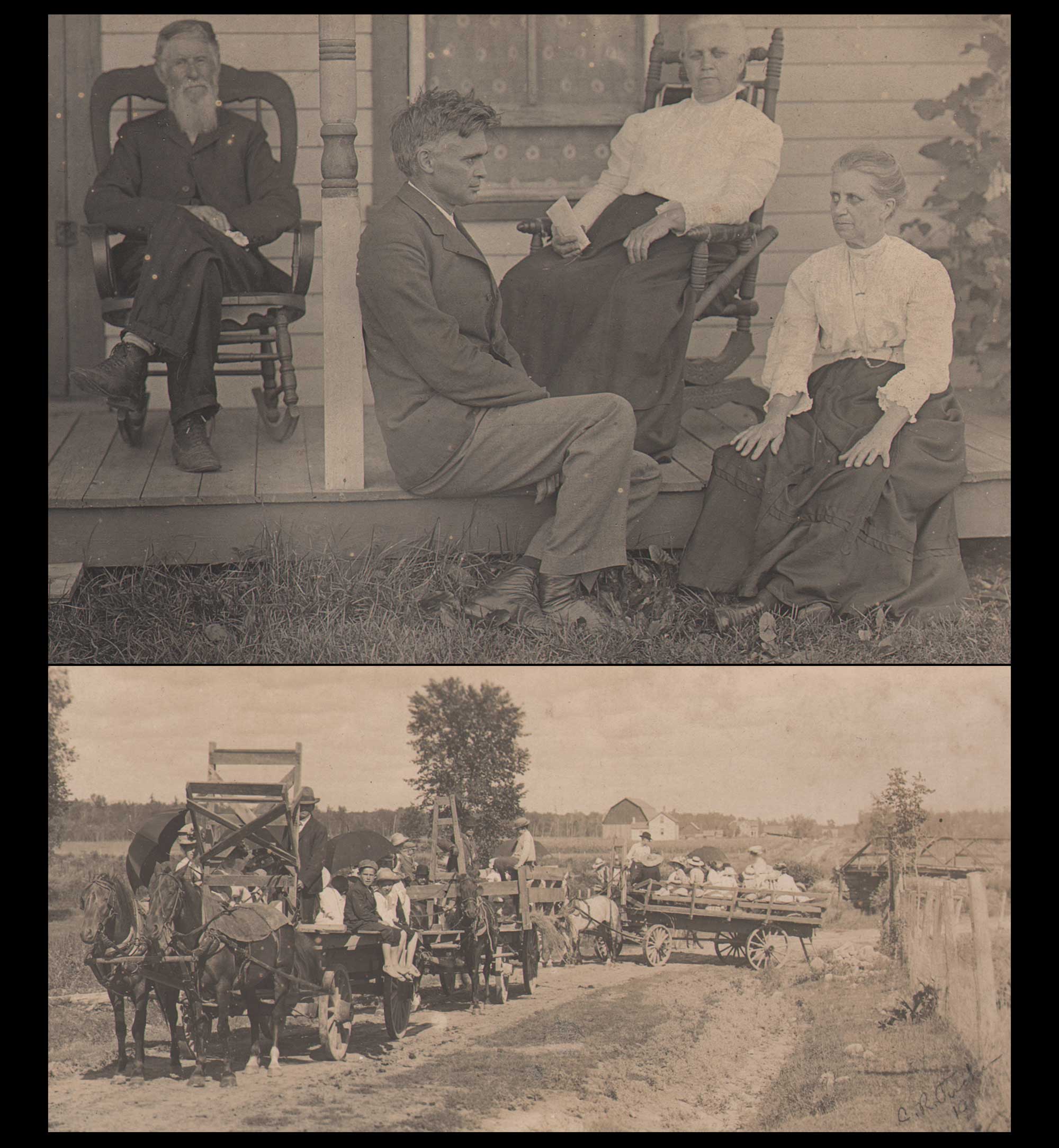

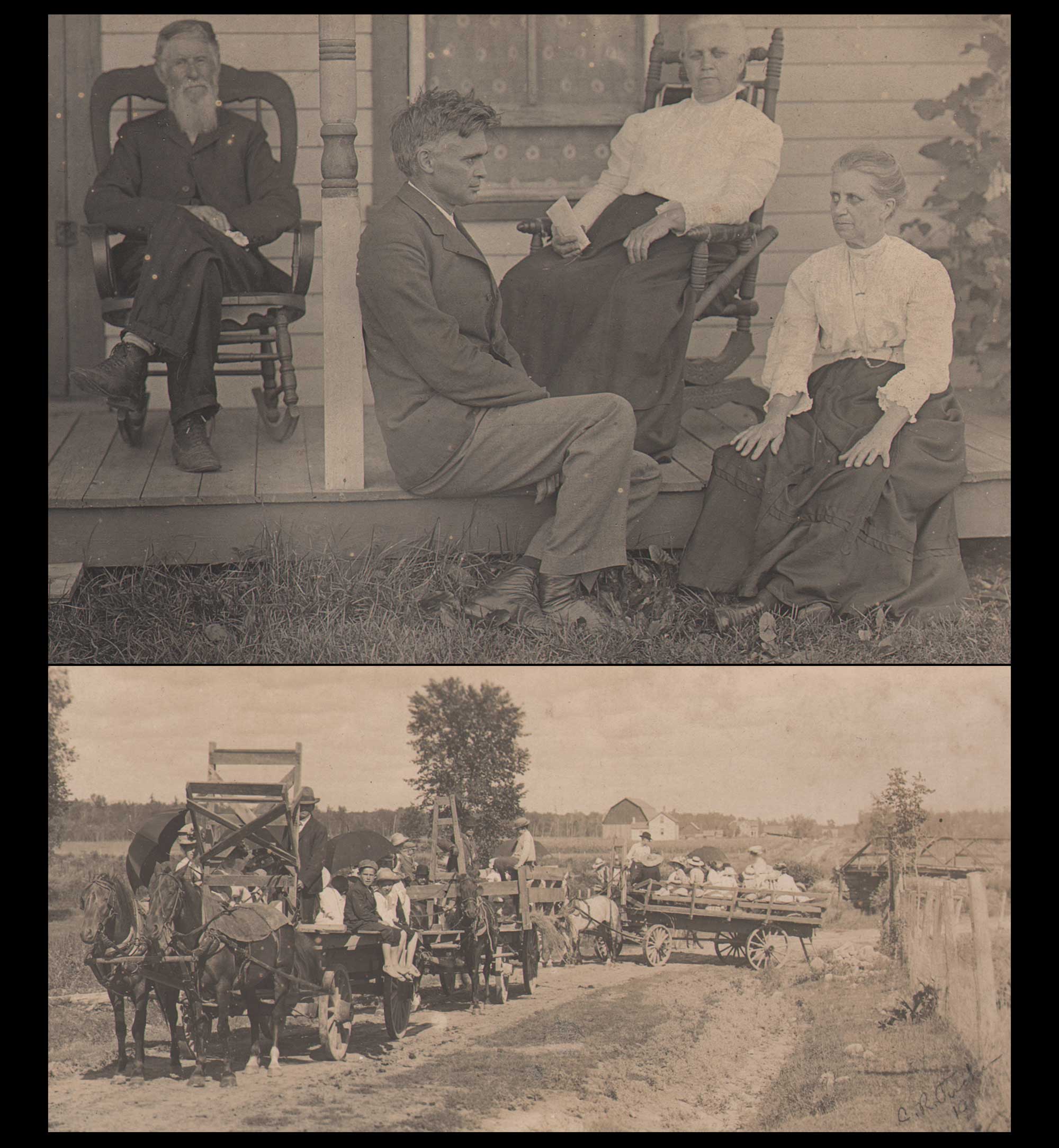

Mother & Son: Top: “Royalton, Wisconsin Family Group”, Bottom: “Wisconsin Sunday School Outing”, 1908 (top) and ca. 1908, printed 1910?, both: rppc gelatin silver postcard & bottom: unmounted gelatin silver print: Top: 8.4 x 13.1 cm, Bottom: 6.6 x 15.7 cm, C.R. Tucker, American 1869-1956. The photographer, seated at center, and mother, Myra F. Tucker: 1848-1927, seated at right, look towards each other. Myra’s sister, Susan A. Talbot Phillips, 1848-1922 sits behind them, along with her husband Sewall A. Phillips: 1839-1912, at far left. Sewall had been a member of the WI State Assembly and worked as a teacher. Bottom: three large horse-drawn wagons ferry a large group of children and adults during what is believed to be a Sunday school outing, possibly in Spencer, WI. The print is signed and dated at lower right corner. Both: PhotoSeed Archive

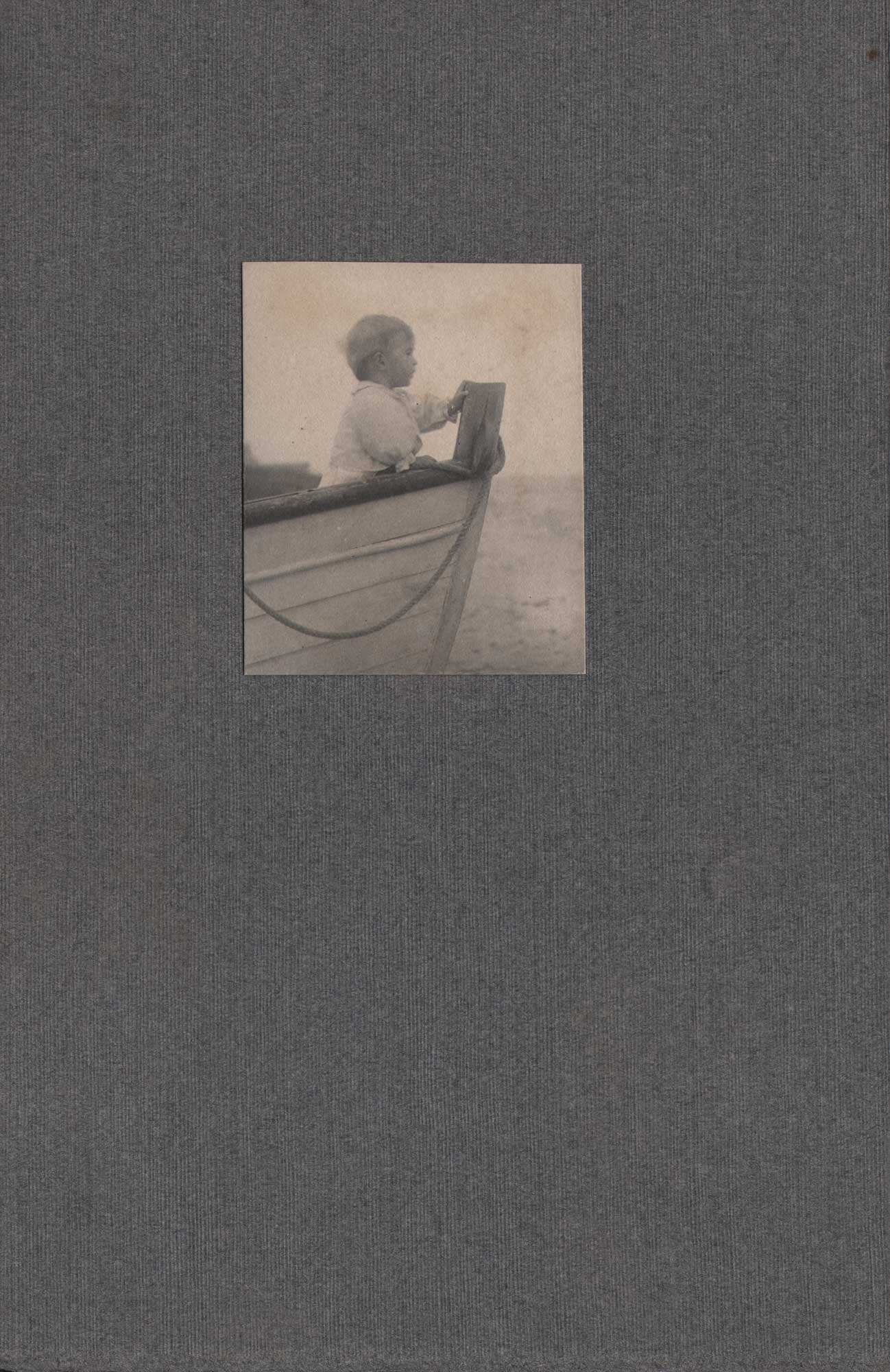

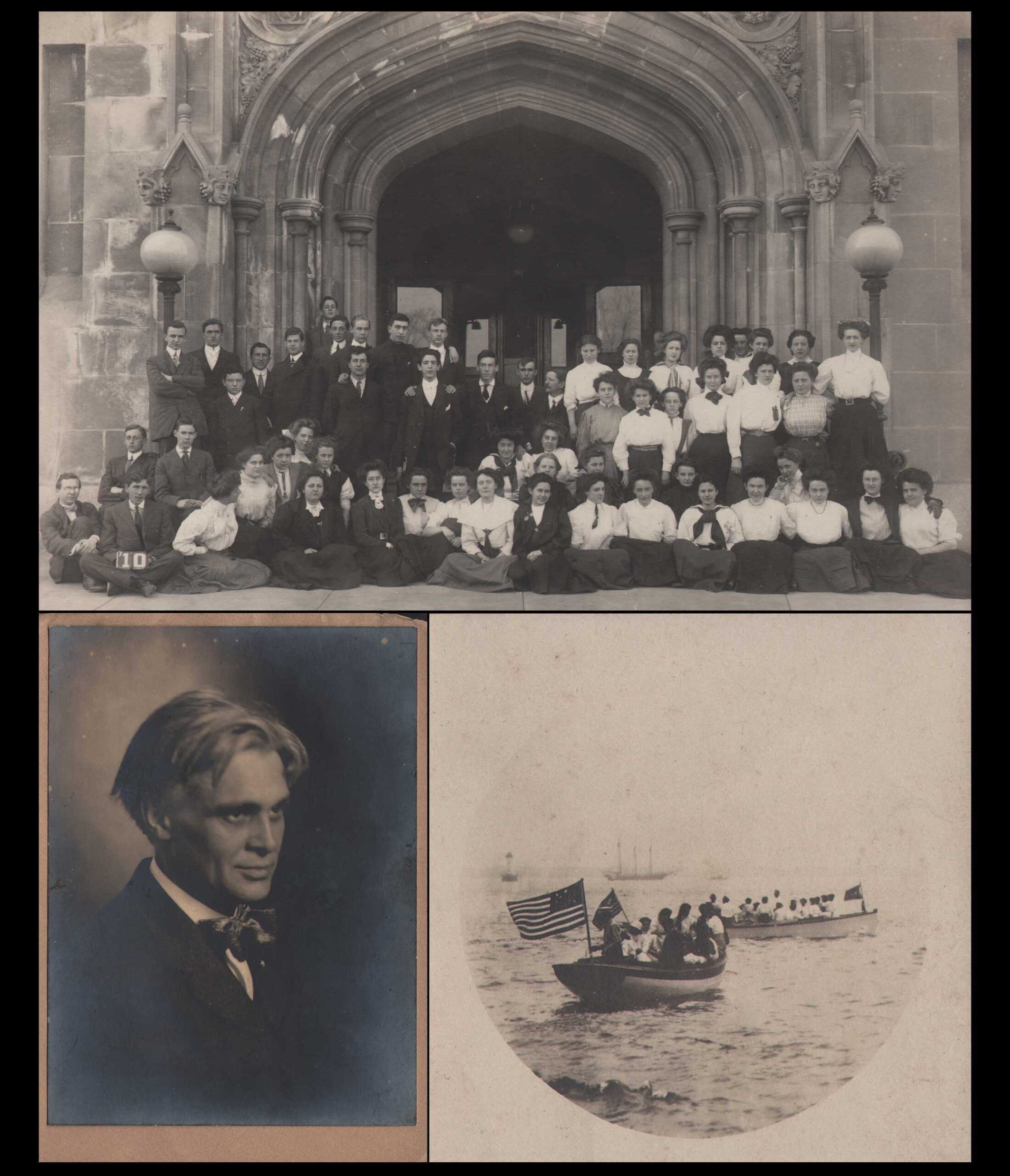

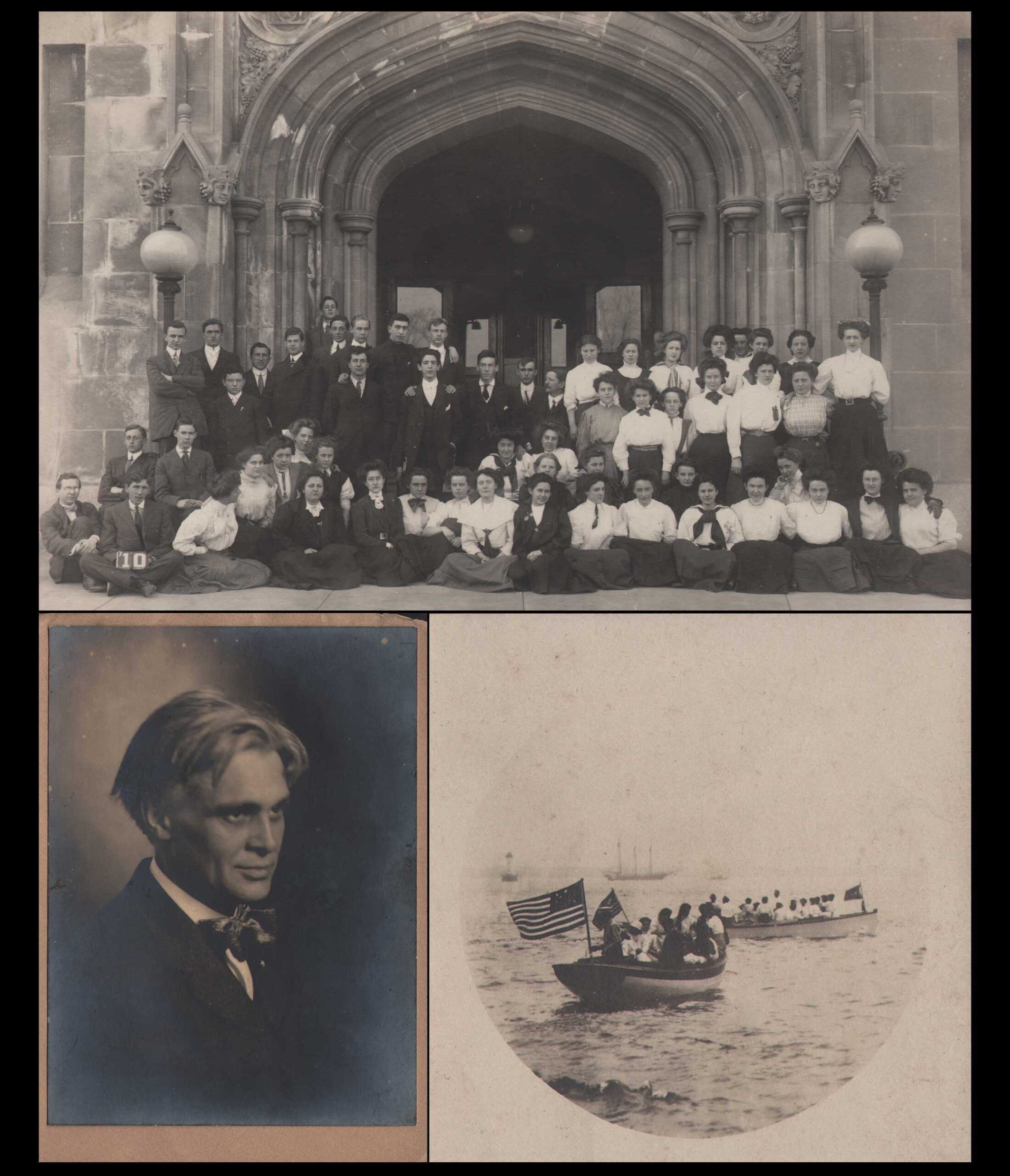

Curtis High School: Top: “Class of 1910: Curtis High School”, Bottom left: “Portrait of Charles Rollins Tucker”, Bottom right: “Around Staten Island”, all: ca. 1910, unmounted and mounted gelatin silver prints, probably C.R. Tucker, American 1869-1956. 18.7 x 24.1 cm, portrait: 13.2 x 9.8 | 14.7 x 10.4 cm, boats: 6.0 cm roundel on 9.3 x 7.2 cm photographic paper. Note student seated in front row at far left holding #10 sign. This signifies these are Curtis High School students, class of 1910. A vibrant community school in the 21st Century, it first opened in 1904, with Tucker teaching here until 1914, when he was put in charge of the Tottenville Annex. A formal, tousled-hair (self-portrait?) portrait shows the artist with his ever-present silk cravat. The dates 1910-1915? are written in unknown hand on mount verso. Small, open steam launches, with boat at foreground flying an American flag, make their way in the waters around Staten Island in a student outing, taken about 1910. All: PhotoSeed Archive

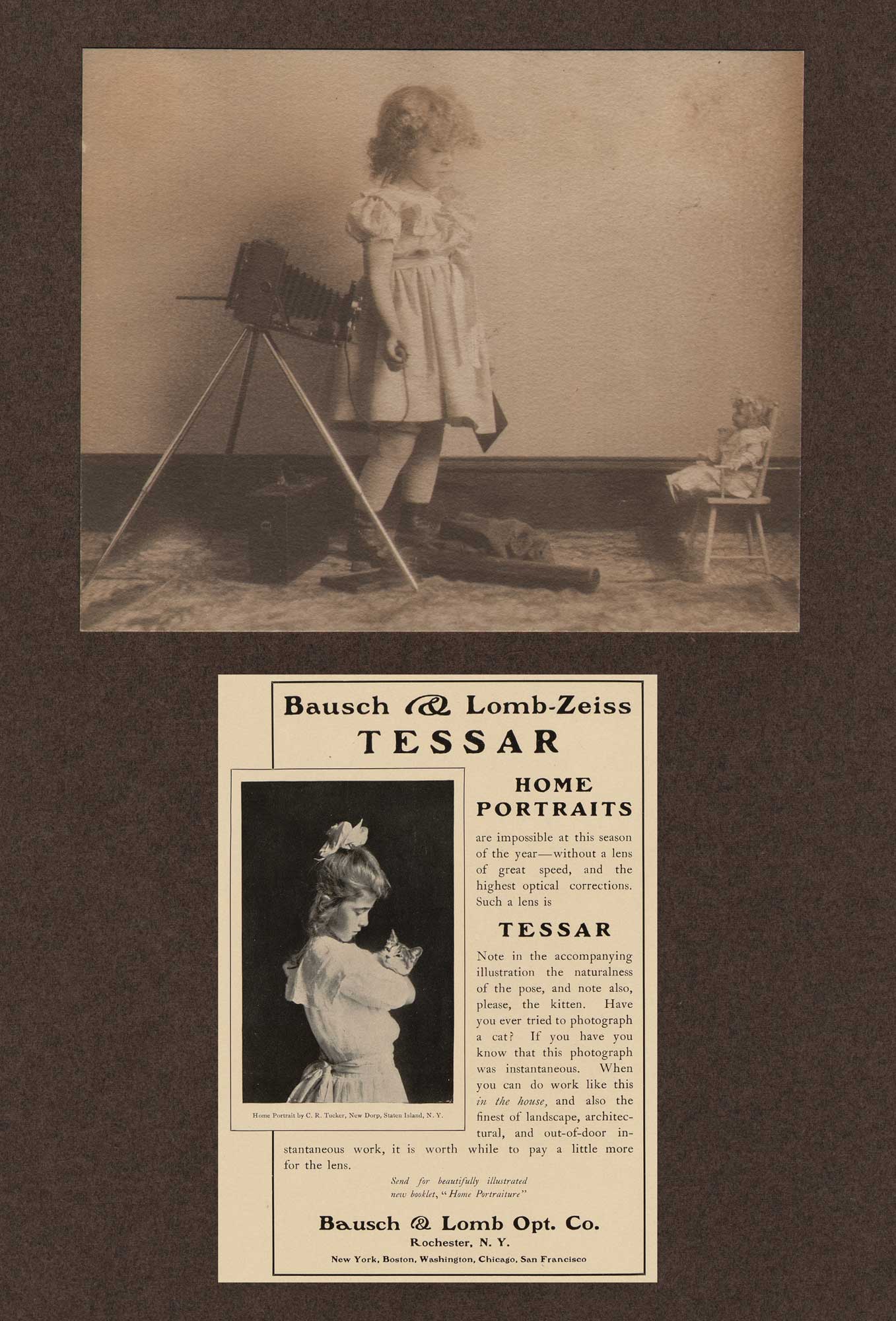

And all the while, the photographic evidence taken in promotion of his hobby, both inside and outside that teaching career, was most important to him. He used his amateur camera to photograph some of his students, even going as far as displaying mounted examples in his own home, and became, in effect, an in-house yearbook style photographer. For Curtis High School especially, Tucker photographed students and teachers alike. He also recorded events, like a class boat trip and sporting scenes: a panoramic showing a a long line of young women exulting in exercise- part of an outdoor gym class.

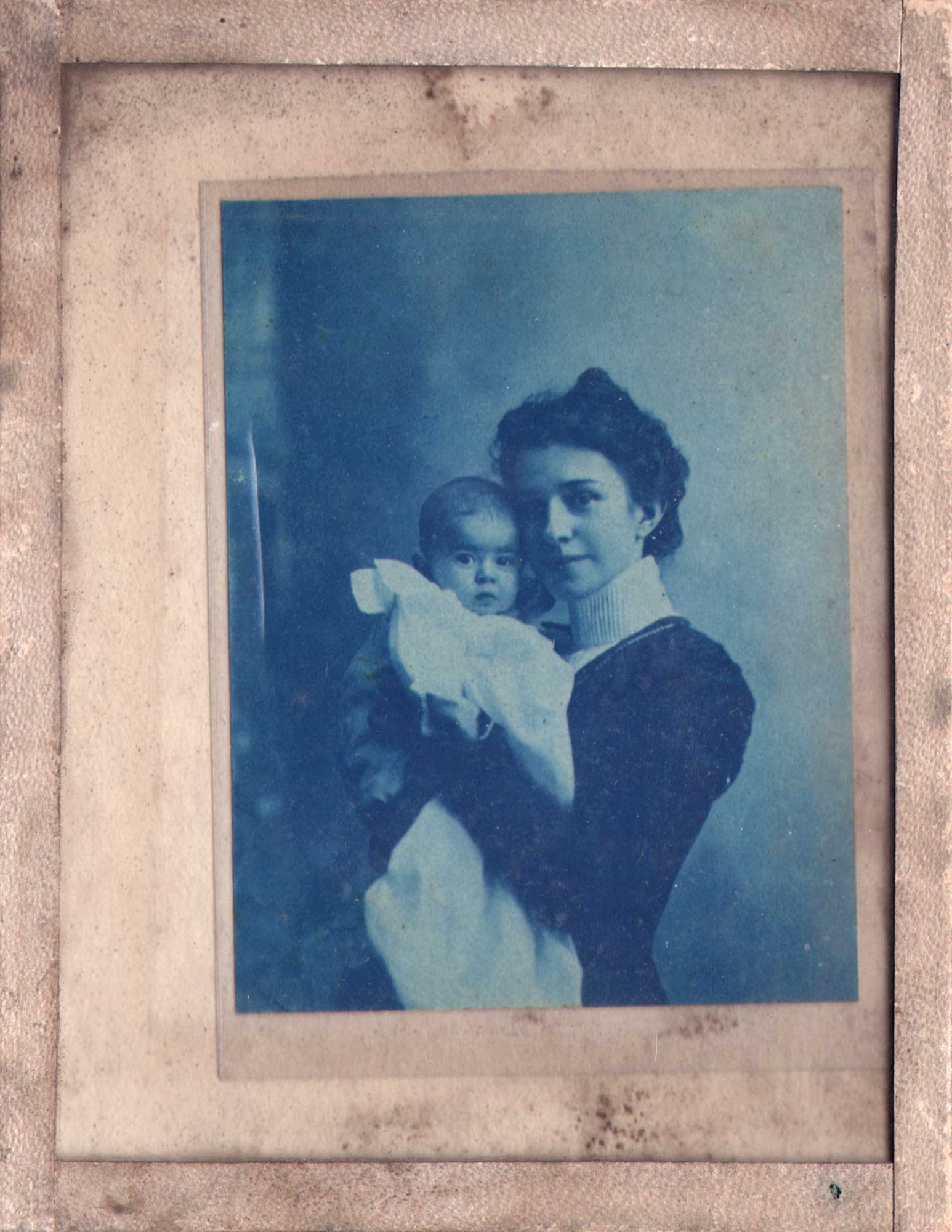

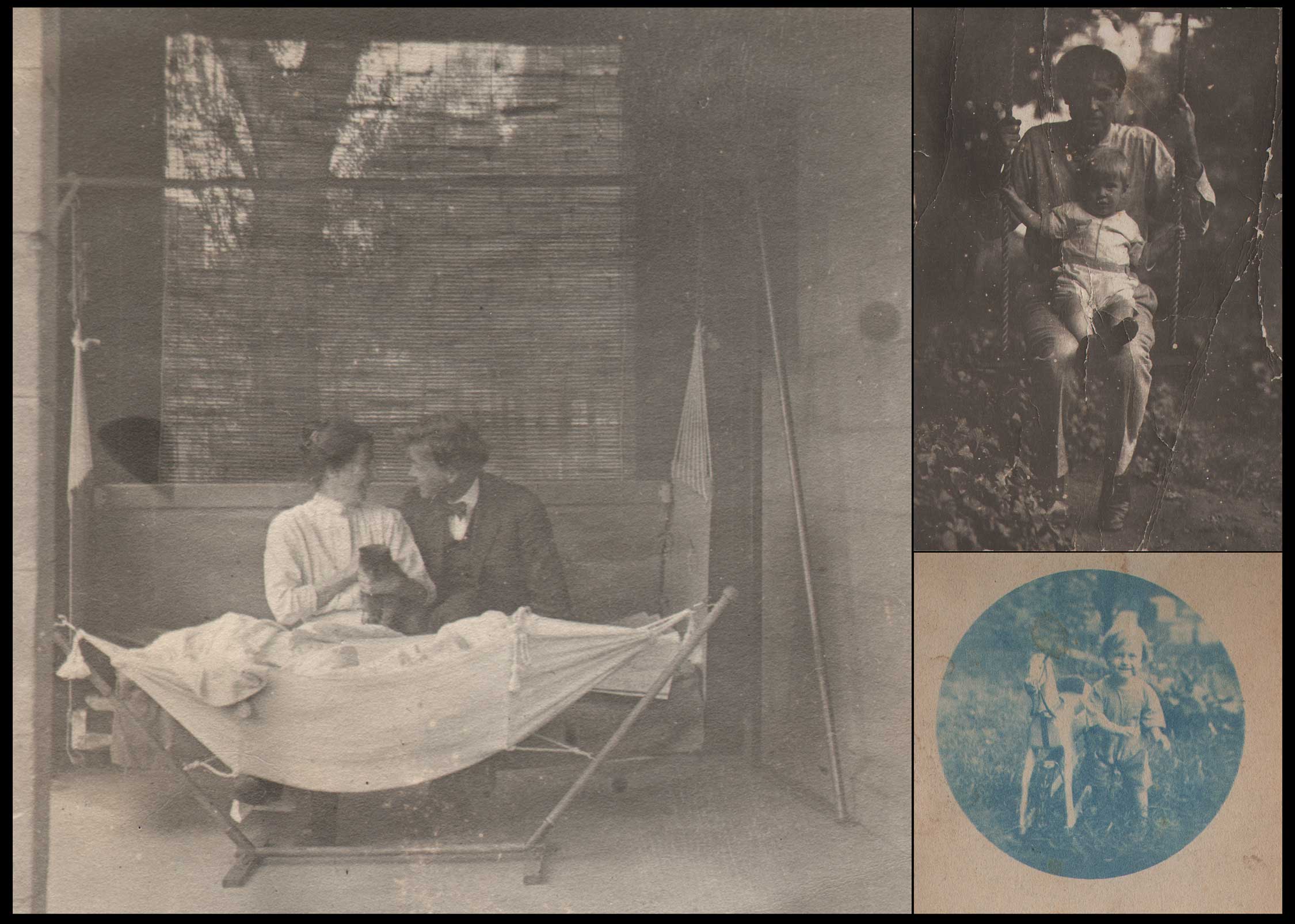

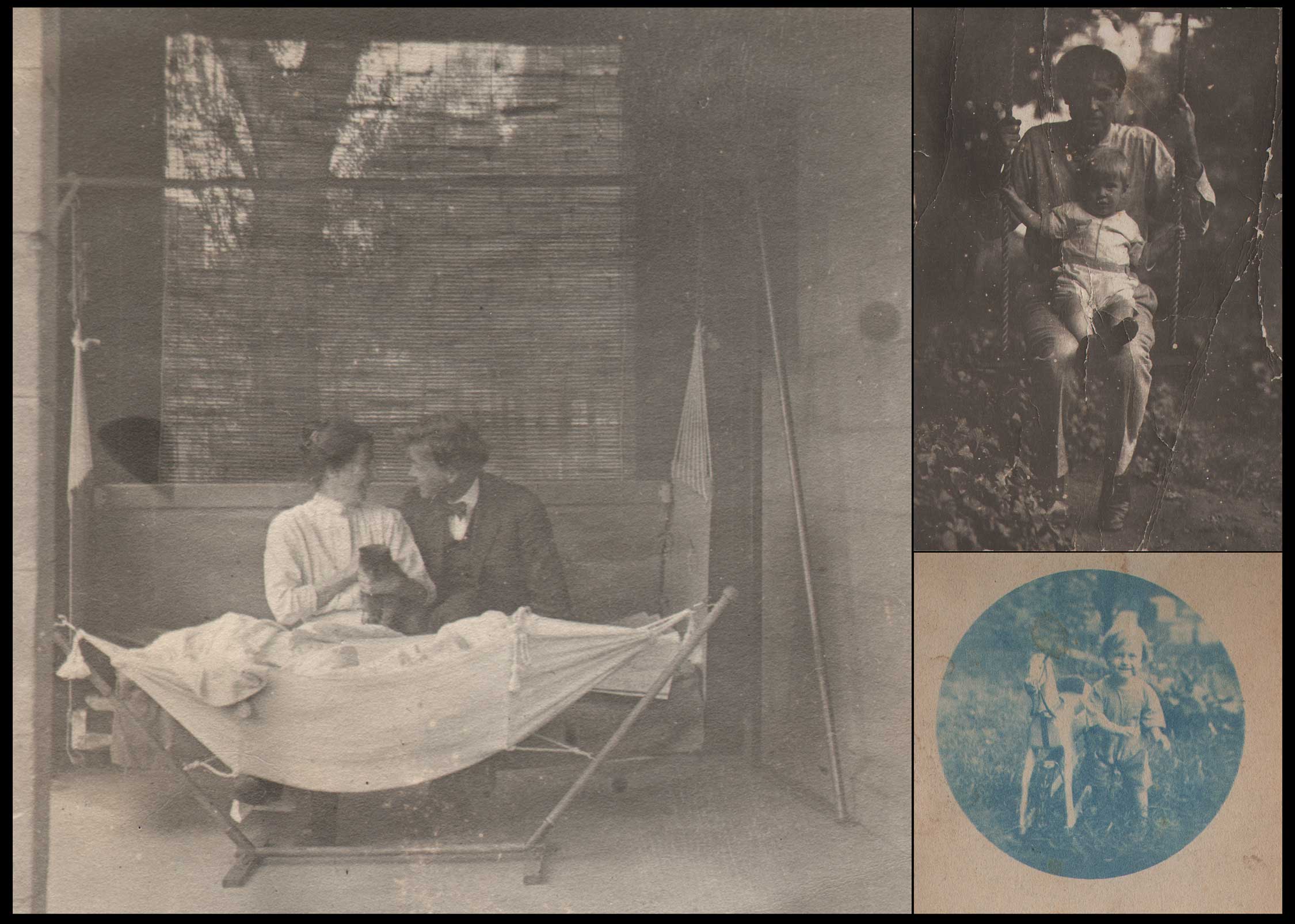

Tucker Family in New Dorp: Left: “Charles, Mary & Robert Tucker on Porch”, Right: “C.R. Tucker with son John Robert on Swing”, bottom right: “”Giggle Jerry!”, porch: 1914, swing: 1914, Jerry: ca. 1915-16; unmounted gelatin silver prints and cyanotype rppc, all: attributed to C.R. Tucker, American 1869-1956, and daughter Dorothy Tucker. L: 13.0 x 13.9 cm, swing: 9.5 x 6.8 cm, Jerry: 6.3 roundel on 13.7 x 8.2 cm card. The Tucker family home at 90 Third St. in the New Dorp section of Staten Island welcomed the second born, John Robert Tucker, 1914-1991, in March, 1914. The newborn lies in a hammock on the porch while the photographer and his wife, holding a cat, fawn over him. At right, Tucker goes for a swing with son John Robert (?) on his lap while his third child, Stephen Jeremiah “Jerry” Tucker, 1915-2001, plays with his rocking horse at bottom right. A second cyanotype rppc of this image gives title as Giggle Jerry! on recto and photo credit to his sister Dorothy on verso. All: PhotoSeed Archive

Preserved decades later by his son Stephen “Jerry” Tucker, and subsequently purchased by this archive many years after his passing, these mounted and unmounted photographs-some printed in platinum- are beautiful pictorialist records of early 20th Century American High School life. Some of the hand-written titles on the versos of just some of these mounted and unmounted photographs: “Curtis High School Girl”; “Curtis High School Girl in Costume of a Play”; “Apple Blossoms”: a genre photograph celebrating Spring featuring a student wearing a long dress ornamented by sunflowers; “Curtis HS Elocution Teacher”, and many others.

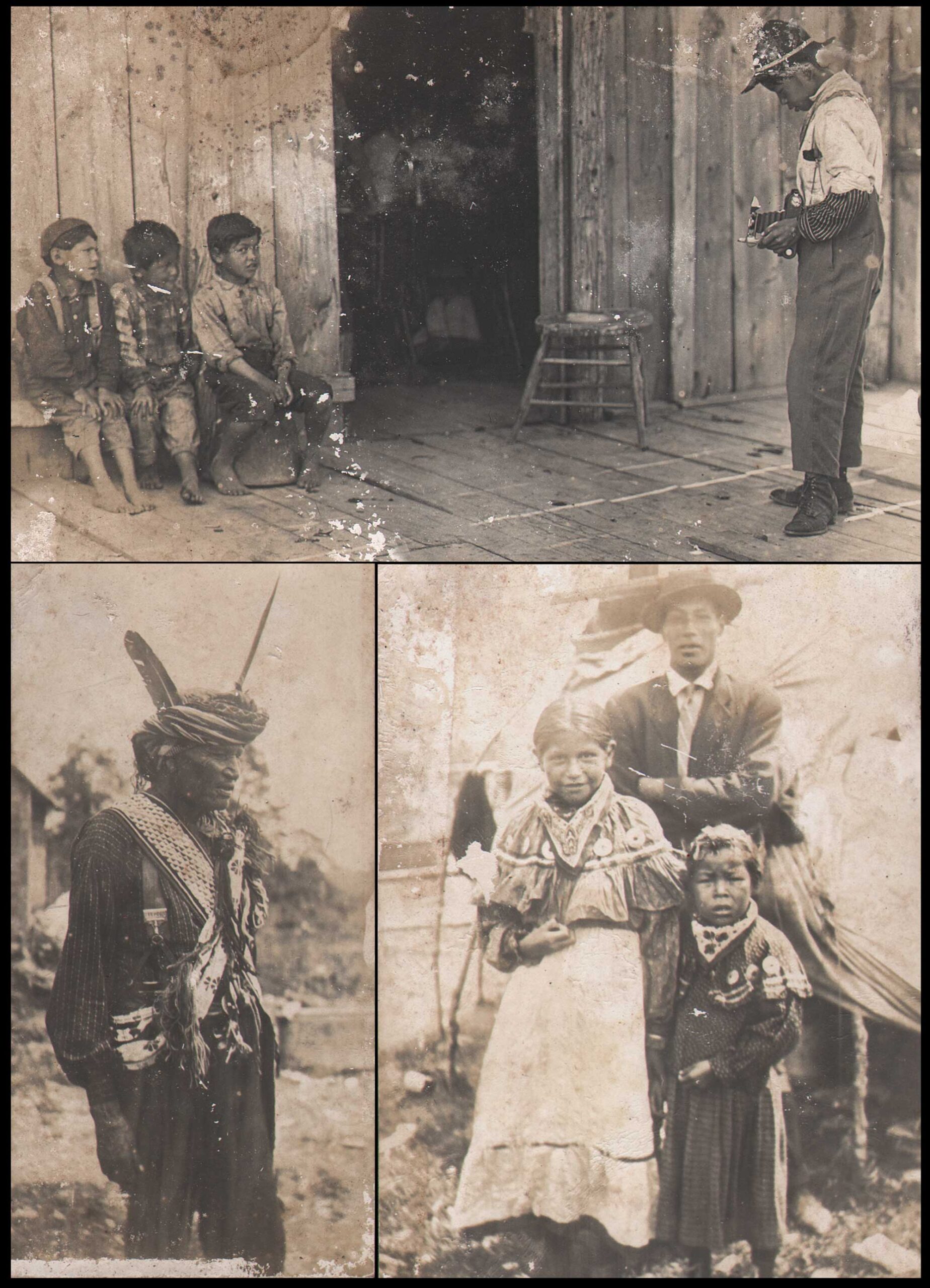

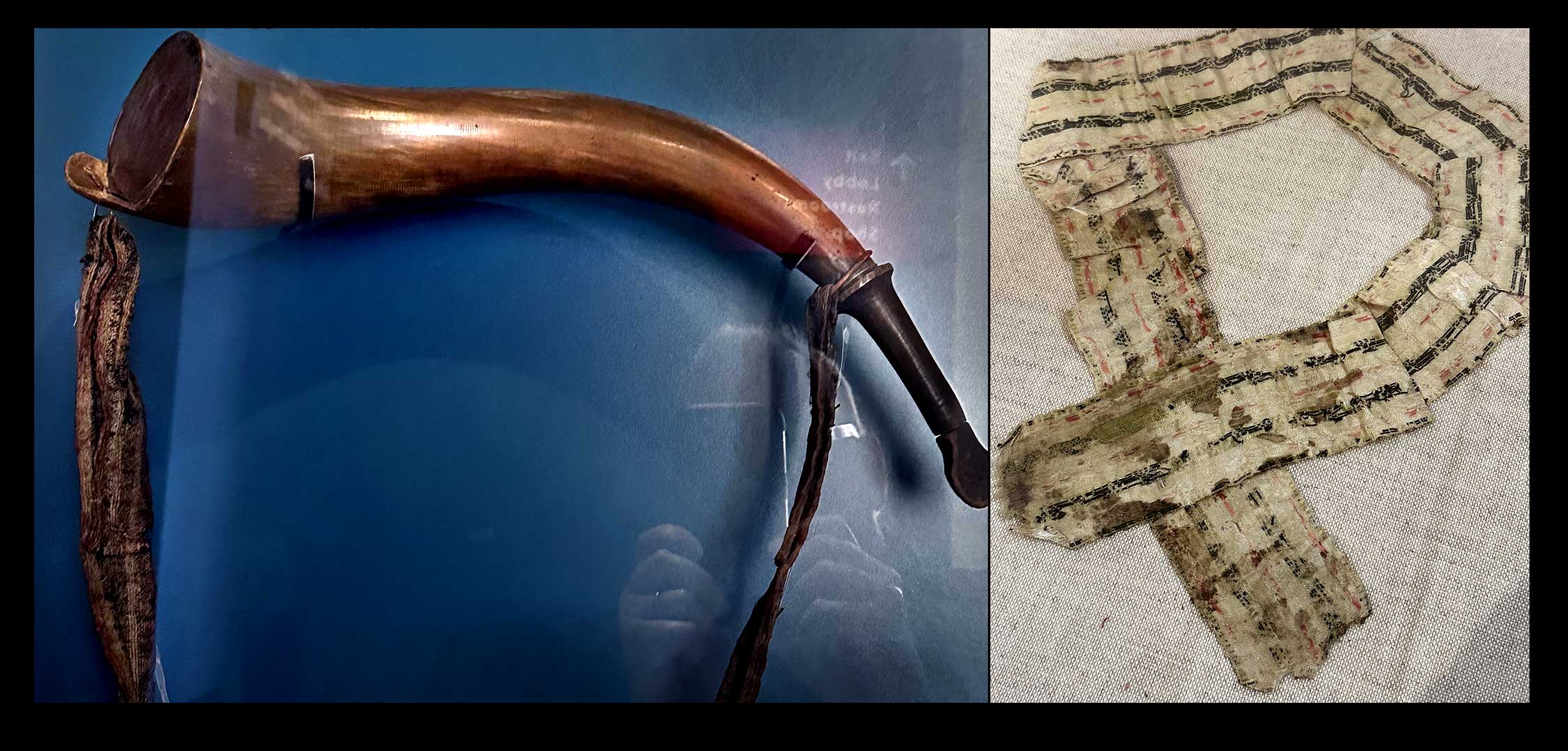

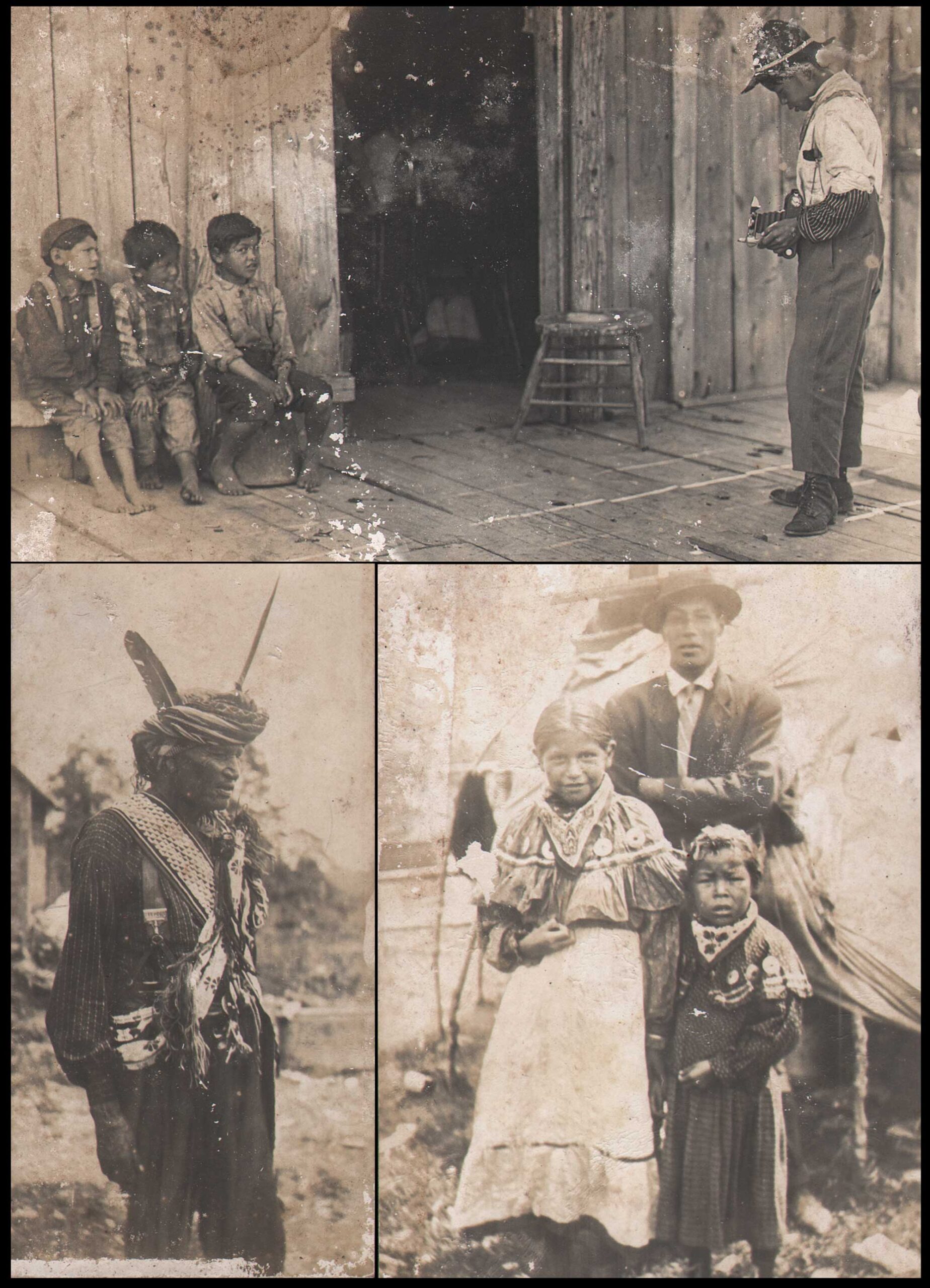

Exploring Native-American Cultures: Top: “Man Photographing Seated Children”, LL: “Native-American Man”, LR: “Native Family Group”, all: ca. 1910-15, unmounted gelatin silver prints, attributed: C.R. Tucker, American 1869-1956. Top-LL-LR: 10.9 x 15.9 cm, 9.9 x 4.9 cm, 10.2 x 6.8 cm. Tucker was known to give public lectures on Pictorial Photography in 1908 and, pertaining to this grouping of photographs in 1916: an illustrated lecture for children described as “A Visit to the Wisconsin Indians”. Although degraded by the elements and digitally cleaned up here, these were found with the larger Tucker archive: photos he is thought to have made during frequent visits to Wisconsin to visit in-laws. Given the sad history of forced assimilation by the US Government by which Native-American children were placed in American Indian boarding schools throughout WI (and the greater US) it cannot be ruled out the top photograph may have been taken at such a school: the subjects in the other photographs not so much because they wear native clothing. Other photographs not shown depict a sweat lodge. All: PhotoSeed Archive

Mayflower Descendant & Later Life

“I had a lot of fun tracing ancestry back to counts and no-accounts, especially the early American families. I found 6 Mayflower ancestors (John Alden was one) 11 Revolutionary ancestors, one Indian, one witch (hanged in Salem, 1692). The Ball and Adams families (whence President Washington and the Adams)”. –Charles Rollins Tucker

In the late 1930’s and through the early 1950’s, Tucker was living in Brooklyn and active as the Vice-President of The Alden Kindred of New York City and Vicinity. As a long-descended related “cousin” of Mayflower passenger John Alden, the Alden Kindred was then, and is still today, an active Mayflower descendant society named after English pilgrims John and Priscilla Mullins Alden. Before the untimely passing of the photographer’s wife Mary in 1940, Tucker and his wife would host chapter meetings in their home. Later, in the pages of the Alden Kindred “Gossip”, a newsletter reporting on the happenings of the society as well as the private accomplishments of its members, the musings regarding “cousin” Tucker were duly reported.

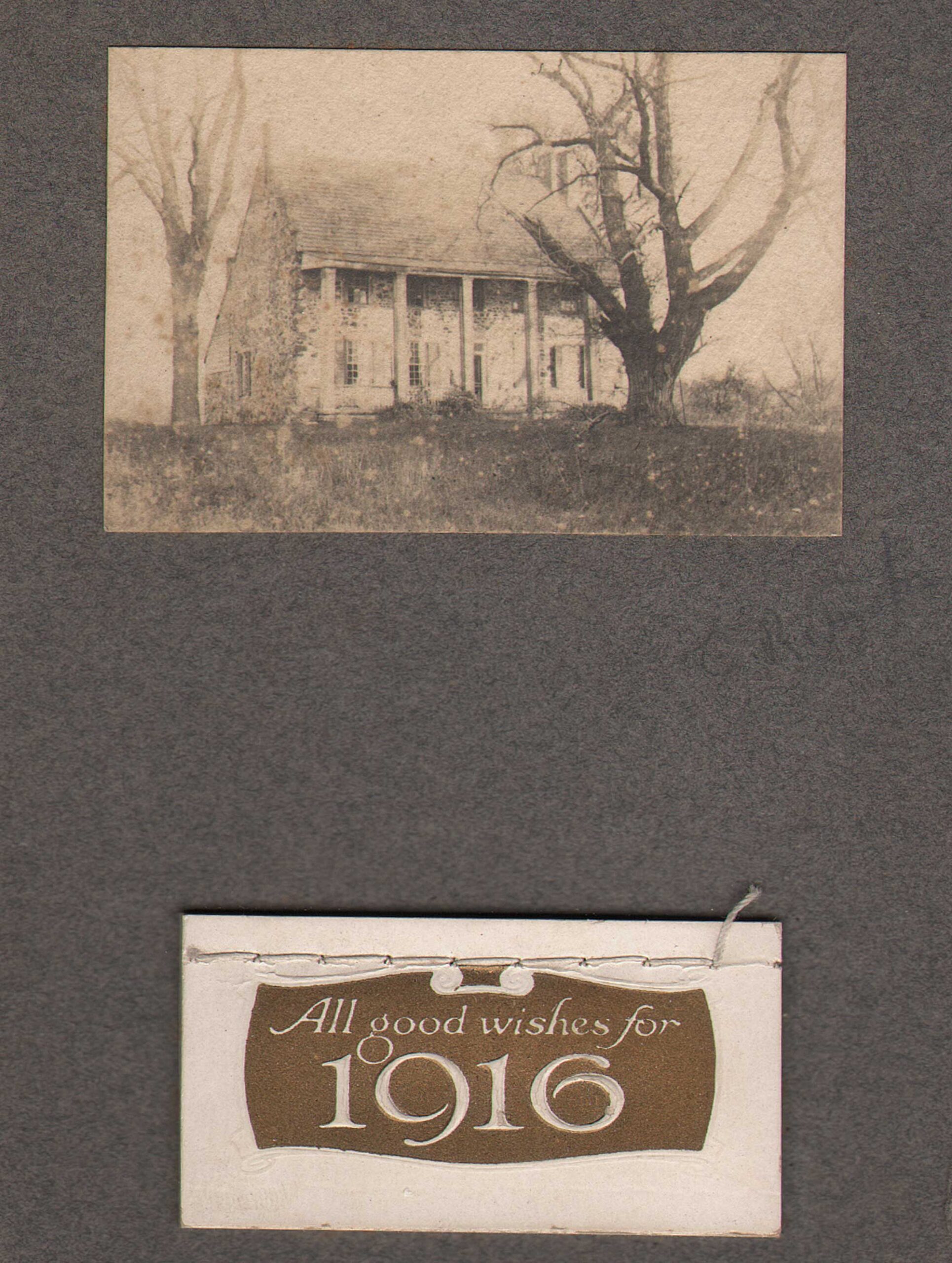

American History Preserved: “Conference House: Tottenville, Staten Island”, ca. 1905-10, mounted platinum print for 1916 calendar, C.R. Tucker, American 1869-1956. 4.4 x 6.7 | 13.9 x 8.8 cm. A Staten Island resident with a passion for American History, it’s not surprising Tucker would photograph one of the oldest buildings on the island. Also known as the Billopp House, it was here on September 11, 1776 that a meeting was held by Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, Edward Rutledge and others with Lord Howe, commander in chief of British forces in America, in an unsuccessful attempt to halt the American Revolution. A landmark and museum today, the home is shown in the early 20th Century when columns supported a long front porch- no longer present. Signed on the mount by the artist, the 1916 calendar may have been a promotion for the South Shore Savings and Loan Association, of which the photographer was president of that year. From: PhotoSeed Archive

Farming Home in Vermont: Top: “Tucker Farmstead, Randolph, Vermont”, LL: “Charles & Mary Tucker with Buckets on Farmstead”, LR: “When the Mists have Rolled Away”, all: 1920’s, unmounted gelatin silver prints, attributed: C.R. Tucker, American 1869-1956. Top-LL-LR: 16.6 x 25.9 cm, 6.7 x 4.8 & 5.7 x 4.2 cm, 6.6 x 8.8 cm. The Tuckers are believed to have purchased this 125-acre farm, (seen at top photo) located in Randolph, VT, before 1920. The Farmhouse at upper right was enlarged, based on another photo, with a large covered porch. Two fun photos show Charles and his wife Mary, probably holding galvanized metal maple sugar buckets, both coming and going. This pleasing scenic view is believed to be from VT and may be a view from the farm- the title written on the print verso most likely referring to the 1874 composition of the same name by composer James Gowdy Clark. Due to his own retirement from public teaching around 1939, the damaging effects of the 1938 hurricane and the passing of his wife in 1940, Tucker sold the farm in the early 1940’s. All: PhotoSeed Archive

Here’s one example, from a 1949 “Gossip” article with the headline: Charles Rollins Tucker, (Expert with the Camera) showing that even at 80 years of age, the photographer was still passionate for a hobby believed to have begun in his high school years:

The Latest Technology: “Manual Training High School Students Show off Radio”, ca. 1930, unmounted gelatin silver print, unknown photographer, but perhaps C.R. Tucker, American 1868-1956. 25.5 x 33.1 | 27.9 x 35.6 cm. The photographer spent many years teaching at this Brooklyn school, from about 1917-1939. Here he stands in third row at far left looking away from the camera. The group may have been a radio club at the school, and the students display at front right an early radio stamped “Duval Energee” above center of large disc. Duval Radio Products Corp. marketed “radio electron tubes and batteries” under the Duval Energee name beginning around 1927. From: PhotoSeed Archive

Now C.R.T’s. color photographs have carried his reputation along the eastern coast from Key West through Maine. He estimates that he has 3,000 slides. He is expert in catching the significant moods of flowering plants and of little children in their own habitat. His slides in Art League exhibits “steal the show”.

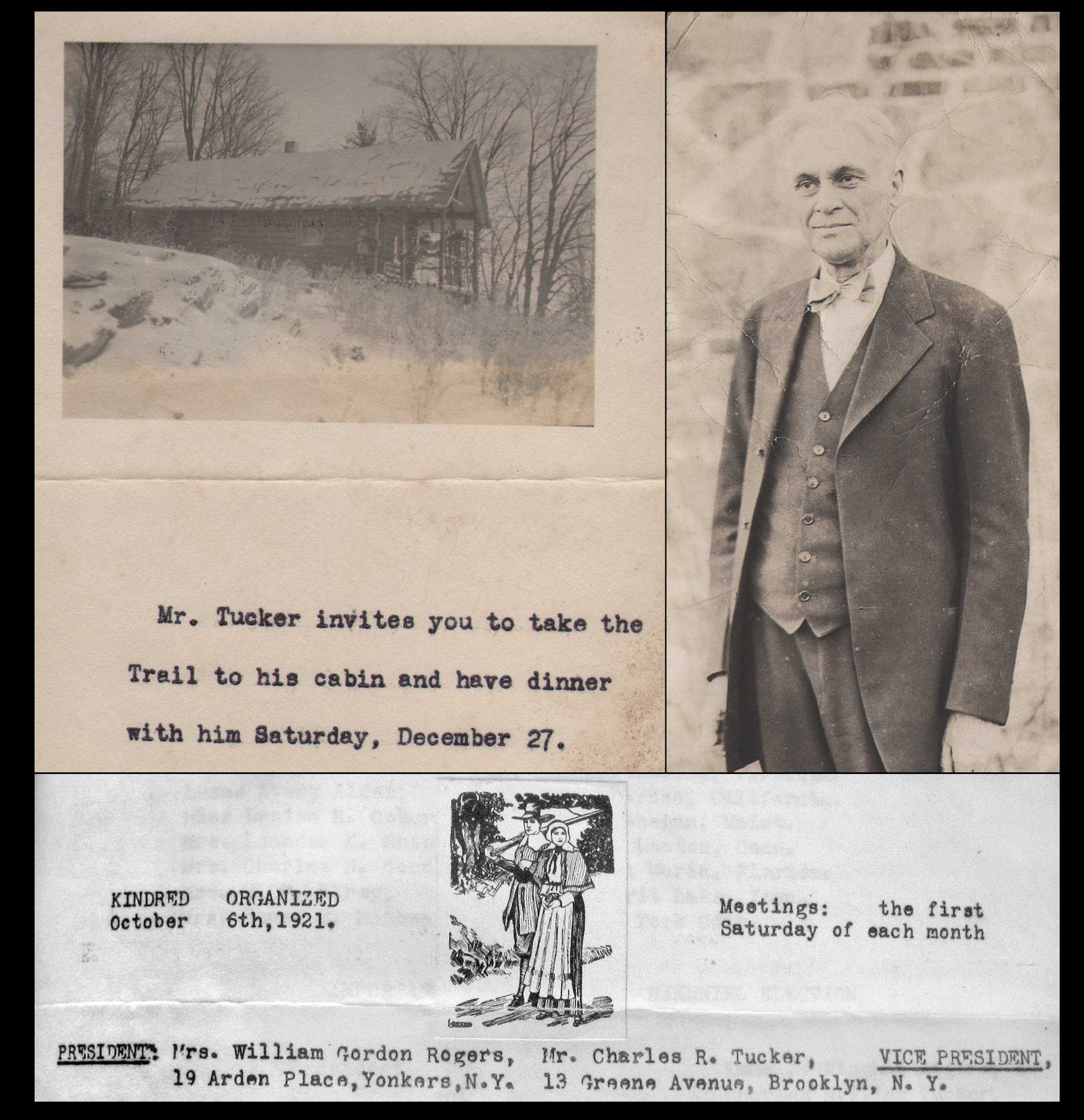

Later Years: Top Left: “C.R. Tucker Dinner Invitation”, ca. 1945-50, Right: “Portrait of C.R. Tucker”, ca. 1935-40, both: POP and gelatin silver print, attributed: C.R. Tucker, American 1868-1956. Bottom: Detail: “Alden Kindred Gossip Newsletter”, Dec. 1934. Invite: 5.6 x 7.9 | 15.2 x 10.0 cm, portrait: 8.6 x 4.5 cm. After retirement and the early passing of his wife, Tucker typically spent the months of May and October in this mountain cabin at Aldenwood in western North Carolina in route to wintering in Mt. Dora, Florida. The owner, E. Huling Woodworth, was a good friend and deputy governor general of the General Society of Mayflower Descendants, whom Tucker met through his role as Vice-President of The Alden Kindred of New York City and Vicinity. The photographer claimed he had “found 6 Mayflower ancestors (John Alden was one) 11 Revolutionary ancestors, one Indian, one witch (hanged in Salem, 1692). The Ball and Adams families (whence President Washington and the Adams)”. Here, a detail of the Gossip, the newsletter of The Alden Kindred, lists him as Vice-President, which he held from around 1933-50. Photos: PhotoSeed Archive, newsletter: Wisconsin Historical Library Archives, Madison, WI.

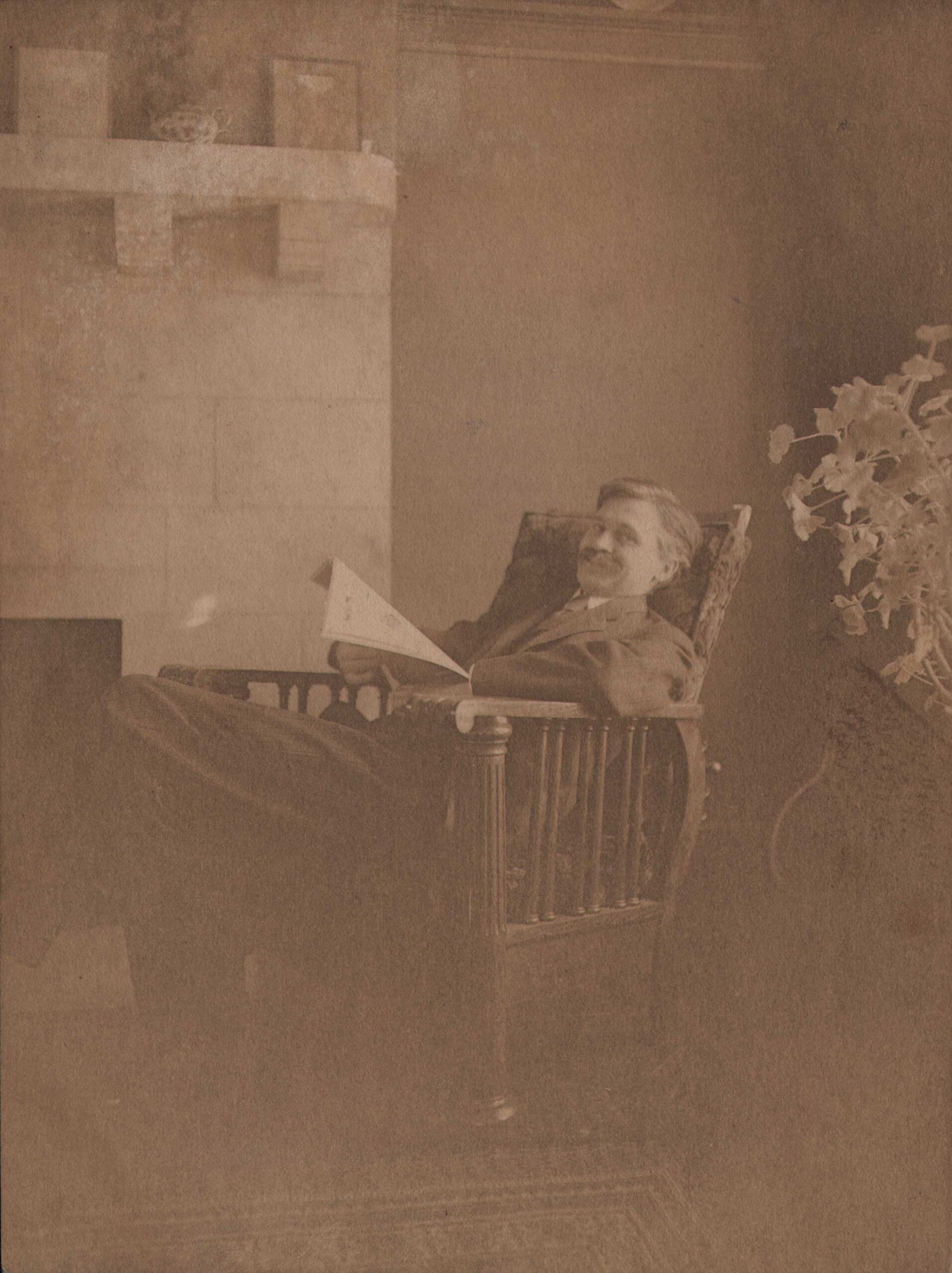

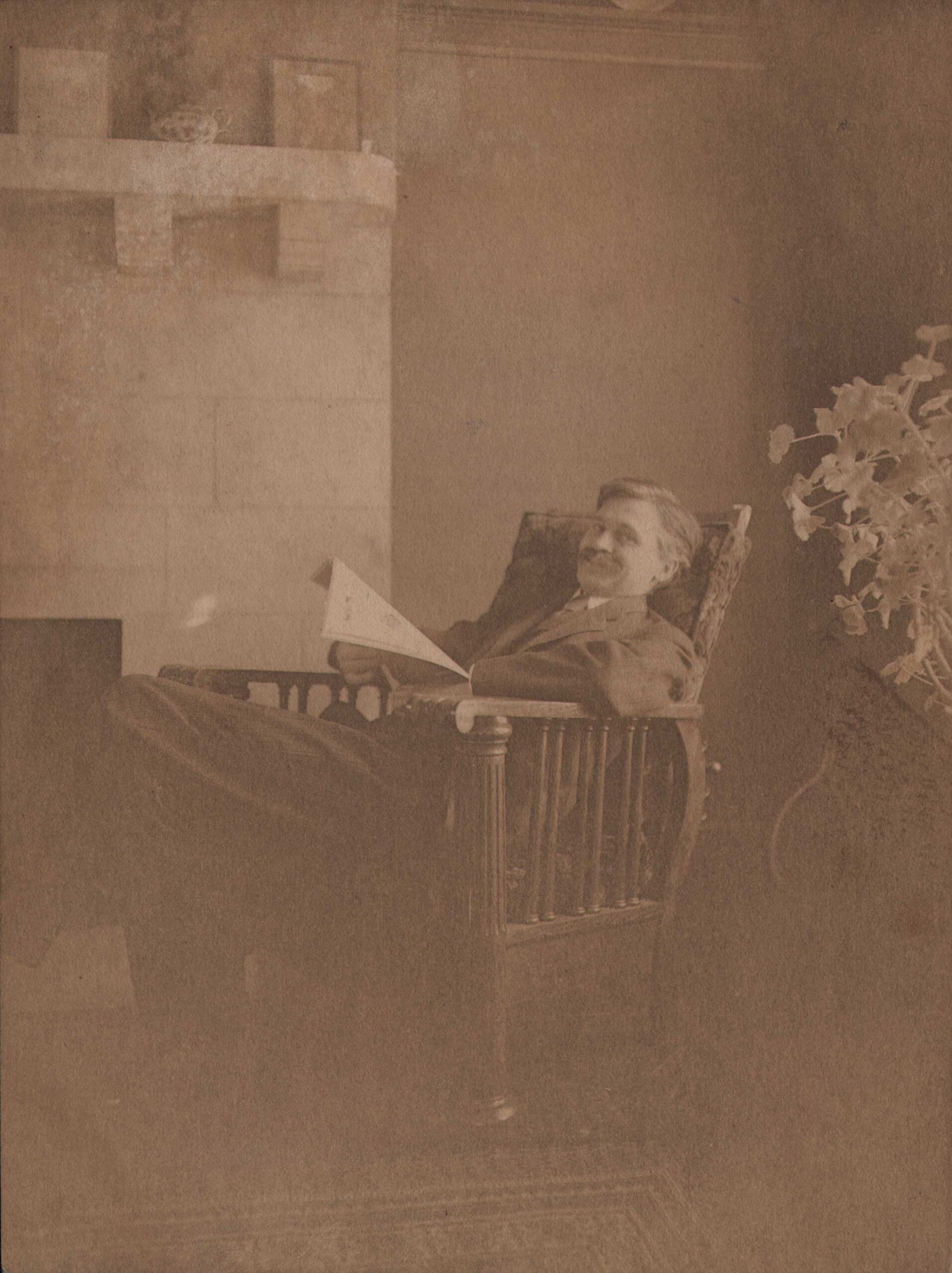

Finis: “Dad in Living Room at New Dorp”, (sic) ca. 1906, unmounted platinum print, C.R. Tucker, American 1868-1956. 19.7 x 14.7 cm. The artist smiles at the viewer while reading from a favorite dining room chair, taken around the same time he and wife Mary and first-born Dorothy moved into their modern Staten Island concrete home in 1906. Charles Rollins Tucker’s life was a series of wanderings- a game of musical chairs in which he wore many hats, made many friends, taught many children, and fortunately for us, made a photographic record throughout. A description in his 1956 obituary seems appropriate with this last photograph of the artist, in the sense he would pass on much later in one of those chairs, albeit figuratively, something his known demeanor of “lovableness and gentle humor” might have allowed him a chance to wink back at us from the future, as he “went to sleep in his chair, in his tiny little home” the last time. From: PhotoSeed Archive

From the same article, the invocation of Shakespeare as poet ultimately defined him, his optimistic view of life made relevant from all its ordinary moments, and here, with photographic evidence for the ages:

Mr. Tucker loves people, but does not need them to keep himself happy and busy.- Shakespere climaxes him as “seeing good in everything”.

Historical Timeline: Charles Rollins Tucker: 1868-1956

1868: Born in Canton, MA on December 18. (source: Tufts College Yearbook) A major discrepancy exists: his headstone indicates 1869, and his 1956 obituary details in the Middleborough Gazette stated he died at 87 years old.

1880: Charles, 11, living with family in Hubbardston, Worcester, MA. His father George is a farmer and mother Myra a housekeeper. (George Lewis Tucker: Jan. 16, 1843-May 19, 1907) (Myra F. Tucker: 1848-1927)

1887: Graduates from Stoughton High School, Stoughton, MA. In his class of 15 students, he was one of only two who graduated. In 1892, his younger brother Lewis L. Tucker, would not graduate.

– Matriculates at Tufts College, Medford, MA in September, in the “Philosophical course”.

1889-90: At Tufts, he is Secretary of the Camera Club in his junior year and member in his senior year; Secretary and treasurer of Reading-Room Association, 1889-90; member of the Sketch Club as a sophomore; member of the tennis club earlier.

1890: He’s the Vice-President of the 1891 Junior class at Tufts; self-quotation listed in yearbook: “He has a lean and hungry look; such men are dangerous. -Shakspere“. As a junior, during the annual Prize Speaking and Reading ceremony at College Hall on June 10, he gives the speech: “Plea for the Old South Church”, by Phillips. First delivered in 1876 by Wendall Phillips, the speech saved the Boston landmark church from destruction, affirmingTucker’s interest in preserving and advocating for American history.

1891: Graduates Tufts with bachelors degree, Ph.B. in chemistry and physics.

– As principal of Somerset, MA High School, he began teaching pupils in 15 subjects, in the one-room school located on Pierce’s Bluff off of South Street.

1892: Principal of Procter Academy, Provo, Utah, for one year.

1894: Receives his Master of Arts from Tufts College.

1895: Principal of West Boylston, MA, High School.

1896: Submaster in Quincy, MA High School.

1897: Working in the Educational Department at the YMCA (Springfield, MA Training School)

1898: In September, becomes an assistant instructor in physics at Pratt Institute, Brooklyn, N.Y.

– Marriage to Mary Carruthers on July 29 in Manhattan, New York.

1899: Daughter Dorothy born in Stoughton, MA on August 27.

1900: US Census: living with wife Mary and daughter Dorothy at 73 Clifton Place in Brooklyn.

– Family moves to 4 Wall Street in New Brighton on Staten Island.

1903: Tucker listed as a teacher in the High School Department at Public School 14 located at Broad and Brook Streets in Stapleton, Borough of Richmond, Staten Island. He most likely had been teaching here before 1903. (source: Directory of Teachers in the Public Schools 1903)

– Becomes a member of the Staten Island Institute of Arts and Sciences as well as the Natural Science Association of Staten Island.

1904: Transfers, from PS 14, to the brand new (George William) Curtis High School, where he continued teaching physics. Opened in February, Curtis was the first high school built on Staten Island. (source: notice: School: Devoted to the Public Schools and Educational Interests”, issue for December 25, 1903)

1905: His name appears on the Curtis High School teaching roster published in The Journal of the Board of Education of the City of New York. His yearly salary in 1905 is $1960.00, with a proposed increase for 1906 to $2042.50. His address continues to be 4 Wall Street in New Brighton.

– Receives an honorable mention in the Photo Era Portrait Competition.

1906: In October, Tucker and his wife take out a mortgage for a revolutionary home made entirely of concrete in New Dorp, Staten Island at 90 Third Street from Eleanor Gardner, believed to be the lender. Built ca. 1904-1905, it was designed by Robert Waterman Gardner, 1866-1937, president of the New York Society of Craftsmen, an architect who pioneered using reinforced concrete in residential construction. The Tucker’s were the second owners of the home after the first, W.J. Steel.

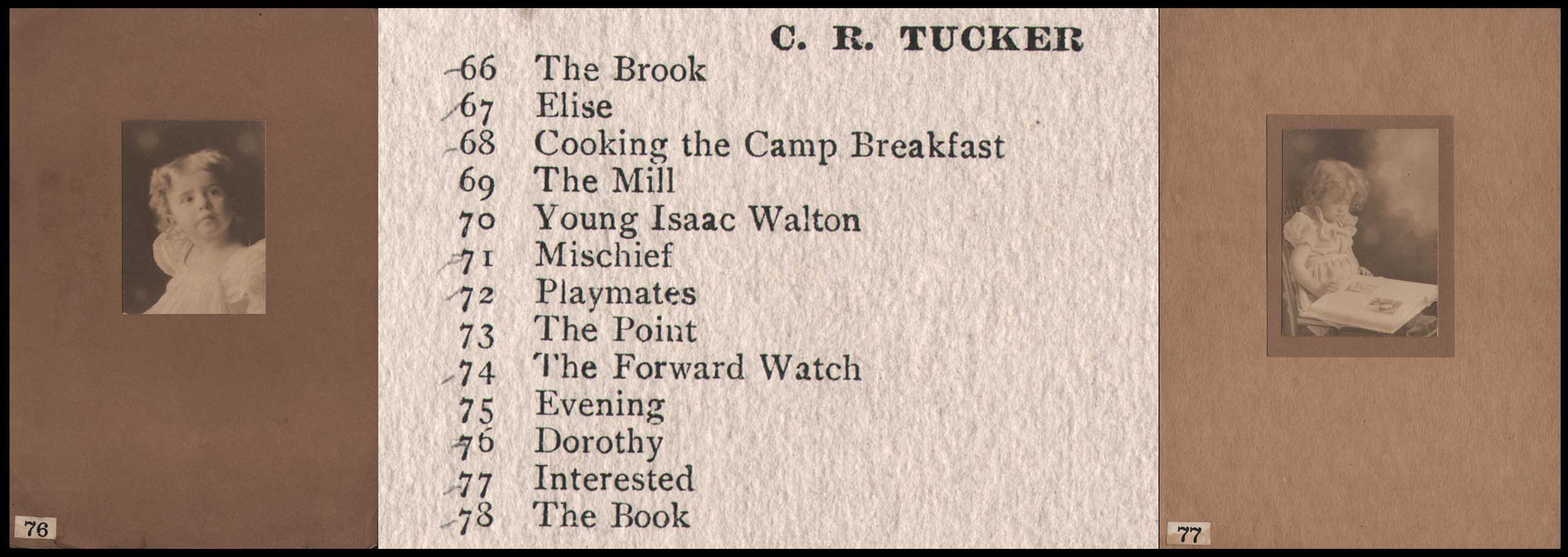

– His photograph “The Mill”, taken in West Bridgewater, MA, is published in the June issue of the Photo-Era. It showed he was a member of The Postal Photographic Club of the United States. The accompanying article outlined the club was founded in early 1885, with membership strictly limited to 40 all residing east of the Ohio River.

1907: In January, a portrait of his daughter Dorothy holding a cat appears as part of an advertisement for Bausch and Lomb-Zeiss Tessar lenses “Home Portraits” in Camera Work XVII.

– Tucker now listed as member of the Postal Camera Club, with a history first dating to 1900 and a roster from around the country, including California. One of his award-winning photographs for the club, “Day Dreams”, held by this archive, was widely discussed and published in 1907.

– Writes article: “The Pleasures of Winter Photography”, for the December issue of Suburban Life Magazine.

1908: Gives a New York City public schools lecture: “Pictorial Photography” in November and December at Public Schools 62 and 63.

1910: American Photography magazine reports C.R. Tucker is a member of: “A New portfolio club has been organized among the advanced workers in the territory east of the Ohio River and north of Washington, D. C.” (other members include: W. H. Zerbe, C. F. Clarke, S. B. Phillips, Miss Katherine Bingham, H. W. Schonewolf and others) “Membership is by election after circulation of samples of work, and only those of marked ability are desired.”

1911: In what was probably a recalibration of the earlier 1910 portfolio club, The Photo Era announces the formation of: The New Postal Photographic Club: C.R. Tucker of New Dorp is a member: “A New pictorial Photographic Album Club has just been started. It has not yet been christened, but a vote is now being taken to determine its title.”

“The album is making its first round and the prints contained therein show most painstaking efforts to put it on a parity with any similar club of the country, and when we take into consideration the active and pictorial workers of this club, we feel justified in predicting its success.”

1914: Tucker’s first son, John Robert Tucker, (1914-1991) is born on March 3 on Staten Island.

– Listed as being in charge of the Tottenville Annex of Curtis High School, and an assistant teacher of physics. Continues to live at 90 Third St., New Dorp, S.I. with the telephone # 922-J Tottenville (Ext. of P.S. 1)

1915: His second son, Stephen Jeremiah “Jerry” Tucker, (1915-2001) is born on April 24th in Vermont.

– At the Tottenville Annex, Tucker heads up the Junior Audubon (Society) Class. An article published by the Macmillan Co. states: “This class has no stated meetings, we are informed by Charles H. Tucker, (sic) the leader, but makes the study of birds a part of the regular work in biology, using the Educational Leaflets as a text-book, and paying especial attention to the economic value of the birds studies.”

1916: The January issue of The Museum Bulletin of the Staten Island Association of Arts and Sciences lists a free illustrated lecture for children by Tucker: “A Visit to the Wisconsin Indians.” A later issue stated 100 people attended.

– While continuing to teach public school, Tucker is listed as President of the South Shore Savings and Loan Association, at No. 11 Sixth Street in New Dorp, Staten Island. The bank commenced business in 1915. The presidency of the bank was taken over by A.J. Grout in 1917, and he assumed that position through at least 1928.

1917: Charles and Mary Tucker sell house at 90 Third St. in April to Dr. Abel Joel and Grace Grout. The home was later purchased in 1922 by the Catholic Diocese for use as Our Lady Queen of Peace Rectory. The present rectory building was built in 1951 and is red brick. It’s assumed the Tucker’s concrete block home was leveled to build the present structure. From the history of the rectory: “Instead, he negotiated with Doctor Grout whose home was situated on Cloister Place and Third Street, but whose property flowed around the corner onto New Dorp Lane. The Grout Home was to become the rectory and the wooded land became the site of the church and school.”

– Dorothy Frances Tucker listed in Tufts College Jumbo Yearbook as matriculated and pursuing her AB degree. Lists being from New Dorp (Staten Island) and graduate of Curtis High School.

– Its believed around this time Tucker joined the faculty of Manual Training High School in Brooklyn, N.Y. as professor of physics, with his 1956 obituary stating he retired from the school about 1939.

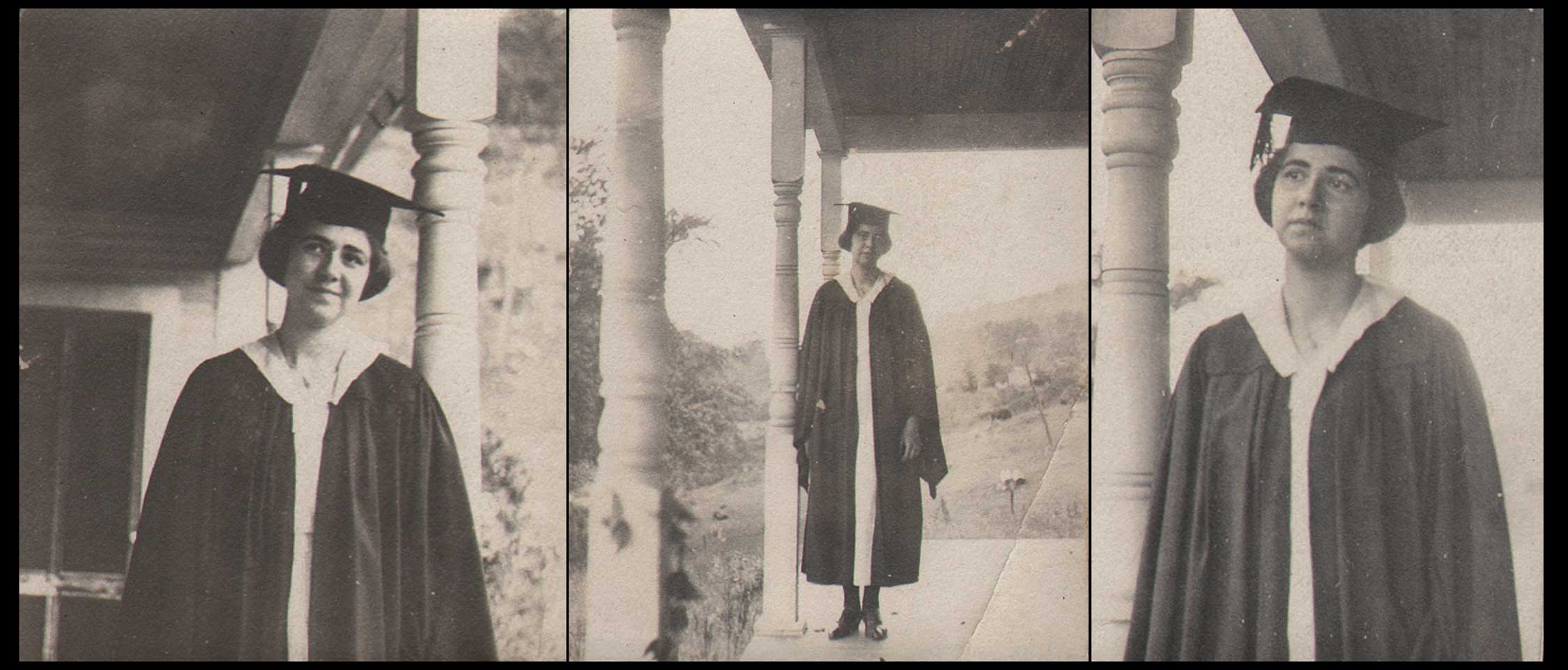

1920: Dorothy receives her Bachelor of Arts degree as a member of the Jackson College for Women at Tufts College on June 21 at the 64th Annual Commencement.

1925: On the New York State Census, Charles occupation is listed as teacher. He lives at 13 Greene Ave. in Brooklyn along with daughter Dorothy, also a teacher, and two younger sons.

1929: Mentioned in Alden Kindred “Gossip” that he was teaching at the Manuel Training High School of Brooklyn, N.Y. At the time, The Gossip was a publication of The Alden Kindred of America, a Mayflower descendant society named after pilgrims John and Priscilla Mullins Alden.

– Additionally mentioned in the “Gossip” this year- pertaining to his photo skills: “The Green Mountain Club has awarded a second prize in a photographic contest to our Cousin C. R. Tucker of Brooklyn and Randolph, Vt. The scene is a delightful section of Lake Mansfield and Nebraska Notch with a cross section of mountain region which is almost impossible to catch with a camera and keep the picture clear in perspective. Both in composition and development very careful thought had been given and the prize was well deserved.”

1932: Writes poem:

Freedom

When the city’s narrow street

Meets the broad highway and gives

Glimpse of space and sky and cloud

Beyond the noisy throngs that crowd,

That is momentary joy.

But when at last my sentence here shall end

Free from this ceaseless shirl of work

and care

(Another waits to better fill my place)

I can forever leave this noisy race,

That will be lasting joy.

1933: Living at 13 Greene Ave. Brooklyn. During this time and much later, Tucker was the Vice-President of The Alden Kindred of New York City and Vicinity.

1934: Charles and Mary Tucker living at 108 South Elliott Place, Brooklyn.

1935: Notice in the Alden Kindred Gossip that Charles Tucker had retired from his teaching job in New York City: “Extra! Extra! Charles Rollins Tucker has retired and does not expect to teach in New York City any longer. The family is moving to Vermont immediately, where their address is “Route 2, Randolph”. Mr. Tucker writes that they will miss the Alden meetings and often think of us on the first Saturday of the month, and shall look eagerly for “GOSSIP”. Bon voyage; bon repose.” (note: his obituary stated he worked until around 1939)

1936: From the “Gossip”: “In August, Mr. and Mrs. Charles Rollins Tucker drove to Ann Arbor, Mich.,via Saratoga, Howes Caverns, Niagara Falls, through Ontario to Detroit, and back by way of Toledo, the Cleveland Fair, Adirondacks, Ticonderoga, Brandon Pass, & c. Son Bob enrolled at the University of Michigan as a senior. The Tuckers will live In Ann Arbor during the Winter, leaving Randolph September 15th. Before going, they were to visit their daughter, Dorothy Tinkham, mother of 2 children, at Rock, Mass.” (Rock Village was located in the town of Middleborough)

1939: Is reported from obituary to have retired from his public school teaching career.

1940: US Census: Tucker living with wife Mary and son Jerry in Randolph, VT

– Mary Carruthers Tucker dies in Boston.

1943: (approx.) Starts Wintering in Mt. Dora, Florida. (one address printed in the Gossip was 916 Grandview Ave.)

1949: The following overview of the life of Tucker appeared in the May issue of The Alden Letter, No. 47:

CHARLES ROLLINS TUCKER, (EXPERT WITH THE CAMERA.)

In the 28 April, 1949 issue of Mount Dora Topic ( Mount Dora, Lake Co., Fla.) Mabel Norris Reese has expressed something of the lovableness and gentle humor which characterize our Alden Kindred official member, Charles Rollins Tucker.

The author quotes from Mr. Tucker: “I tried teaching for 45 years; decided I couldn’t do it, and when they told me they would rather pay me than have me around, I bought a Vermont farm, but I kept on teaching, to try to pay farm expenses; I am now living on the interest of what I lost, trying to be a farmer”.

It was like Charles Tucker to say nothing of the heartbreak when Death took his companionable wife, while they were still Vermonters. Nor is there mention of the 1938 hurricane which crashed through their precious capital, in sugar maple groves.

Nothing of the anxious loneliness while World War II held son, Jerry, for 4 years in the Pacific.

Miss Reese notes that Charles was born in Canton, Mass.; at 4 years, with his family traveled in a prairie schooner to Missouri; shortly afterward moved on to Wisconsin for 5 years in a log cabin; at 10 returned with the rest of the Tuckers to Massachusetts.

There he matriculated in an old red school house – Seems to have garnered a good deal out of it, too- He went to Tufts College and a bachelor degree in 1891. But “not satisfied with being a bachelor, I took another college year to be a Master.”

Charles began teaching pupils in 15 subjects, in a one-room Mass. school; continued teaching as principal of an academy In Utah; went to New York City – “simply because they paid me more money”: stayed there for the rest of his teaching life, as a high school instructor.

As to Charles Tucker’s avocations, he says regarding genealogy: “I had a lot of fun tracing ancestry back to counts and no-accounts, especially the early American families. I found 6 Mayflower ancestors (John Alden was one) 11 Revolutionary ancestors, one Indian, one witch (hanged in Salem, 1692). The Ball and Adams families (whence President Washington and the Adams)”.

Now C.R.T’s. color photographs have carried his reputation along the eastern coast from Key West through Maine. He estimates that he has 3,000 slides.

He is expert in catching the significant moods of flowering plants and of little children in their own habitat. His slides in Art League exhibits “steal the show”.

Mr. Tucker loves people, but does not need them to keep himself happy and busy.- Shakespere climaxes him as “seeing good in everything”.

He spent last October alone in Aldenwood, N.C. a mountain cabin – in a wide spread community of 14 houses, 90 souls and 5 surnames: McCall, Anderson, Devore, Hogshed, Owen. They were 17 miles from a grocery store, 25 miles from a movie – One day the community jammed a mountain schoolhouse to see for the first time an outside world interpreted to them by Chas. Tucker.

For 6 years Mr. Tucker has spent his winters in Florida. Last Dec. 18 he was quietly reading away his 80 anniversary when he heard whispers and stifled giggles: The door flew open, and there a host of children were shouting, “Нарру Birthday, Mr. Tucker!” The head ones were bearing a table radio, which the younglings had “chipped in” to get for their most beloved friend. When Mr. Tucker centers a group of little people, one is minded of a scene in Galilee 2,000 years ago.

Mr. Tucker generally comes back to Middleboro, Mass. in a leisurely trip – This year he is trying to reach Aldenwood, N.C. while the shrubbery, delayed by unseasonable cold spells is in top bloom. Two years ago he and son Jerry took 2300 miles of mountain and valley loveliness into their trailer home of 21 days – Throngs of people have gone along with them.

The children of C.R. and Mrs. Tucker could not but be fine also- S. Jerry, after his 4 years of Pacific war service is with the N.H. Cattle Breeding Ass’n, John Robert is in U.S. Testing Co., Hoboken, N.J., Dorothy, the oldest, retired from Harvard U. library work to be a wife and mother on a Middleboro, Mass. farm. At an annual meeting of Alden Kindred in Duxbury a few years ago we heard this proudest grandfather ever, presenting a lovely first grandbaby as “Miss Priscilla Alden, Barbara Standish” – I think her real name is Barbara Tinkham – and that now other grandchildren have carried on the Alden Standish lines. (pp. 295-7)

1951: Attends 60th reunion of his class at Tufts College, renamed Tufts University in 1955.

1956: Charles Rollins Tucker passes away near Middleboro, Mass., on Monday, May 28.

Obituary: The Alden Letter: No. 132, June, 1956

CHARLES ROLLINS TUCKER, former Vice-President of the Alden Kindred of New York City and Vicinity, went to sleep in his chair, in his tiny little home near Middleboro, Mass., on Monday, May 28 1956, and never woke up. His funeral service was conducted by a Congregational minister the following Thursday, and Burial was in Maplewood Cemetery, Stoughton, Mass. Survivors include a daughter, Mrs. Roland Tinkham of Middleboro, two sons, Jerry Tucker of Susquehanna, Pa. and Robert Tucker of Teaneck, N.J., three grandchildren and at least one great-grandchild. His wife, the late Mary (Carruthers) Tucker, died in 1940.

Mr. Tucker would have been 88 in December and was born at Canton, Mass. He graduated from Tufts College in 1891 and attended the 60th reunion of his class in 1951. He held the degree of Bachelor of Arts and also Master of Arts.

After teaching in Utah some years, he returned East and was in YMCA work for a short time and taught at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, N.Y. He then entered the New York City public school system and served as teacher and principal on Staten Island. But the major portion of his teaching career was as professor of physics at Manual Training High School in Brooklyn, N.Y. He retired about 1939.

For many years, he retained a summer home on a 125-acre farm at Randolph, Vermont, where several of the New York Kindred visited him. He was an ardent hiker and had several times hiked the entire Long Trail of Vermont, from Massachusetts to Canada. After retirement, he gave up the Vermont farm and he and Mrs. Tucker went to live with their daughter at Middleboro. Mrs. Tucker soon died, and Mr. Tucker established a little summer home near his daughter’s house. He spent his winters in Florida, except for one winter sojourn in Phoenix, Arizona, and the last two winters when he stayed in Massachusetts. For several years, in going to and from Florida, he spent the months of May and October at ALDENWOOD, the mountain cabin of the Huling Woodworths in western North Carolina. He took thousands of color photographs and gave slide showings in Florida, Arizona, South Carolina, Georgia, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York, Vermont, New Hampshire, and Massachusetts. Many people have had many hours of enjoyment from his beautiful slides and the sweet whimsicality of his accompanying comments. He will be sorely missed by many.

Alden Letter is indebted to Huling Woodworth, his host at Aldenwood, for the outline of Mr. Tucker’s life quoted above. June 8, ’56. E.A.P. (Eudora Alden Philip-editor) note: E. Huling Woodworth was the deputy governor general of the General Society of Mayflower Descendants who compiled the “Mayflower Register” of descendants. He died in 1964.