That experiment of American Democracy, culminating in our annual celebration today of the Fourth of July holiday, has survived 241 times since that fateful Philadelphia signing, in 1776, of a remarkable document giving notice to the larger world our Declaration of Independence and legal right to self-rule, with benefits.

Detail: “Asbury Park Boardwalk”: Laural J. Jones, American: 2004 digital scan taken from ca. 1938-1945 black and white film negative: A woman who may have become the photographer’s second wife, Edith, sits with a white hat on her lap on a bench at center in this bustling summer boardwalk scene taken at the Fourth Ave. entrance. The 18-hole Asbury Park Obstacle Golf course can be seen directly behind the bench at center and at left. Courtesy: Private Florida Collection

Freedom of expression, and with it speech as it relates to the right of picking up a camera and chronicling daily life in one own’s creative bent without fear or favor are American freedoms held dearly by this website. I long hope our presently divided country can see the worth and value of all her citizens understanding each other and getting along for the betterment of the whole.

Detail: “Fifth Avenue Military Parade”: Laural J. Jones, American: 2004 digital scan taken from ca. 1938-1945 black and white film negative: Possibly taken before World War II, a little girl at far right holds an American flag as US infantry troops march up Fifth Ave. in New York City. The location of the photograph is W. 27th Street. The former La Primadora Havana Cigar shop can be seen at center at 234 Fifth Ave. and a Horn & Hardart automat is in the lower floor retail area next door at 236 Fifth Ave. Courtesy: Private Florida Collection

Not Lost Forever: the work of Laural J. Jones

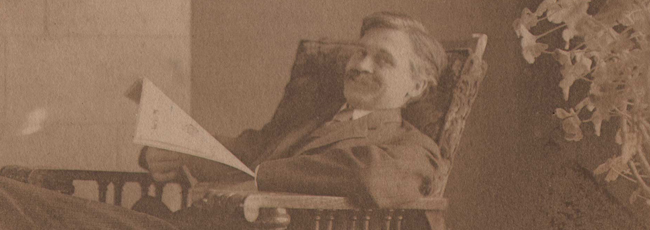

With the blessing of a good friend who owns this documentary work in the form of developed 35mm black & white film negatives, and dating more than 20 years past the offerings of the more typical pictorialist body of work featured on PhotoSeed, I’m taking advantage of America’s national holiday to introduce to the world a gentleman who knew a thing or two about self-expressionistic ideals enshrined in our Constitution, the work of American amateur photographer Laural J.(ohn) Jones. (1897-1980)

Detail: “RMS Queen Elizabeth in New York Harbor”: Laural J. Jones, American: 2004 digital scan taken from ca. 1940-1945 black and white film negative: Although it is unknown when this photograph was taken, onlookers witness the famed 85,000 ton RMS Queen Elizabeth ocean liner in this photo. She initially docked on March 7, 1940 at Pier 90 in quarantine anchorage off Staten Island following a secret voyage to the US from Greenock, Scotland in order to evade German bombers. Courtesy: Private Florida Collection

Reminiscent in some ways to the much larger body of unknown photographs done by Chicago nanny Vivian Maier (1926-2009) after her life’s work was rescued from a storage locker in 2007, Jones work by contrast and fate was preserved in only two shoe boxes. Residing for more than five years in a Florida antique store before being discovered and saved, spooled negatives by Laural Jones along with an assortment of very small printed photographs are believed to have been placed there from an estate sale originating from the photographer’s second wife Edith, who had lived with Laural in the community of Harbour Oaks, south of Daytona Beach.

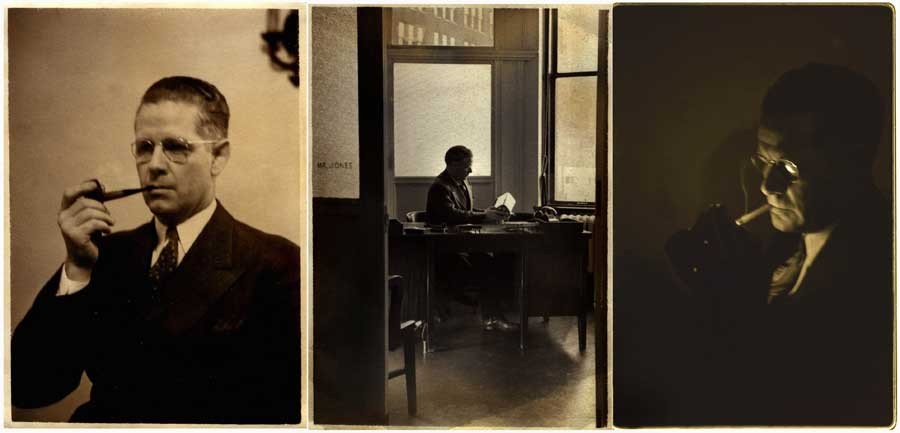

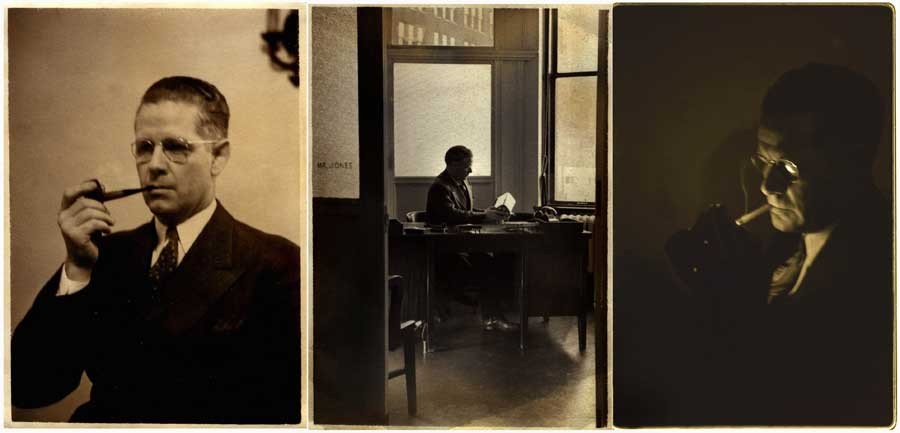

“Self-Portraits of Laural J. Jones: 1897-1980”: Laural J. Jones, American: 2004 digital scans taken from ca. 1938-1953: black and white film negatives: The photographer is seen here in a series of self portraits with the center view taken at his office in New York City, where he was employed as the secretary of purchasing for Bell Bakeries, Inc. Courtesy: Private Florida Collection

Since all that remains are negatives, and with sparse details of his life slowly emerging from US Census and other web resources and records only recently, the Michigan-born Jones is known to have owned the then-new Leica camera sometime around 1938, around the time he is believed to have commenced his early interest in photography. In one surviving photograph stamped 1942 that is an obvious self-portrait, the photographer is nattily dressed and smoking a pipe while he inspects a copy of Popular Photography magazine.

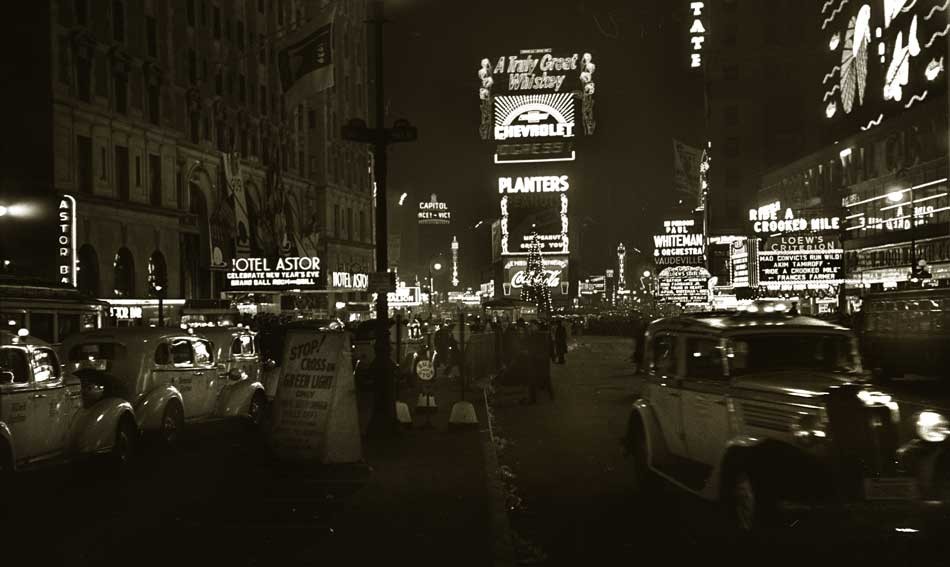

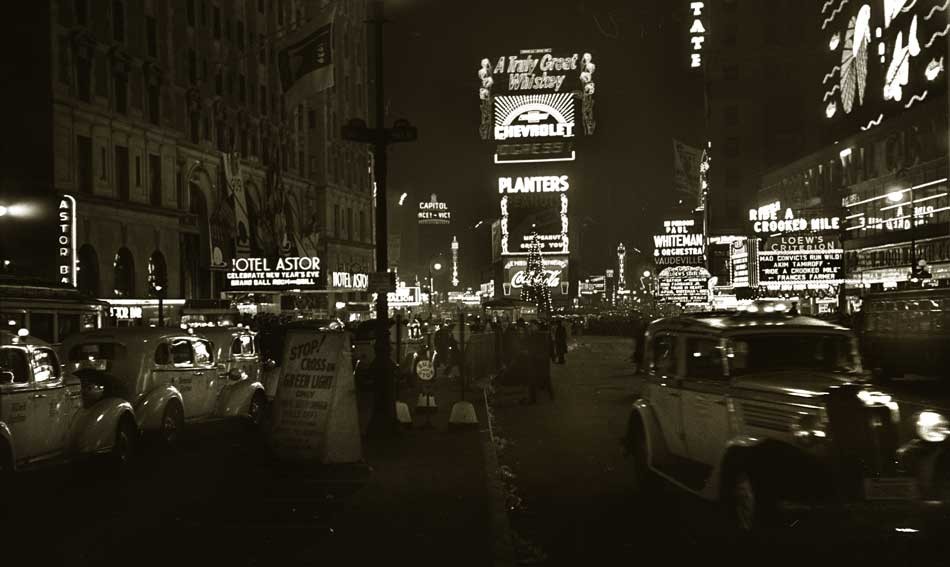

Detail: “1938: Times Square at Night”: Laural J. Jones, American: 2004 digital scans taken from ca. 1938 black and white film negative: In this view showing Times Square at night in New York City taken between Christmas and New Year’s Eve 1938, a large banner for the year 1939 hangs above the entrance to the Hotel Astor at far left which exclaims those to Celebrate New year’s Eve in their Grand Ball Room and Grill. A large lighted Christmas tree is in center background while at far right, the Loew’s Criterion marquee advertises in glowing lights the American movie western “Ride a Crooked Mile” starring Akim Tamiroff and Frances Farmer. Courtesy: Private Florida Collection

Earlier, on Thanksgiving day in 1918, he was first married to the former Ruby A. Armour, (1899-1977) and is listed in a newspaper wedding announcement from the time as being the assistant manager of the Grand Leader Department Store in Battle Creek, with Ruby working there as a clerk. The year of the marriage, the future photographer is described as tall and slender with blue eyes on his World War I draft card, although it appears he was never called up. The couple lived with Laural’s father Mayver Jones, a carpenter for the Advance-Rumely Co., and mother Cora at their home at 129 Somerset Ave. in Battle Creek.

An interesting newspaper account from 1933 showed Laural shared a passion for carpentry like his father, and was also skilled in design. That year he spent several months constructing and designing a custom travel trailer coach in his father’s Someset Ave. carpentry shop meant to “conform with the new stream-line automobiles“. It was: “20 feet in length, maroon color with aluminum top. The interior is divided into two compartments, and is finished throughout in paneled veneer, walnut finish. The forward compartment is furnished with built-in library table, Pullman couch upholstered in brown Spanish leather with chairs to match, and folding typewriter desk, and radio, with an oval rug as floor covering.” The couple also seemed to have the luxery of time and money: they hit the road late that Fall pulling the new coach in route to St. Petersburg, FL, where they spent the Winter.

In 1935, according to his 1980 obituary, Laural moved to New York City from Michigan in order to serve as secretary in charge of purchasing for Bell Bakeries Inc., a large commercial concern with factories throughout the eastern seaboard and beyond. But it’s not clear if Laural’s wife Ruby accompanied him on the new adventure. That’s because 11 years later, the Battle Creek Enquirer newspaper for June 4, 1946 lists the couple receiving a divorce before Battle Creek circuit court Judge Blaine W. Hatch the day before.

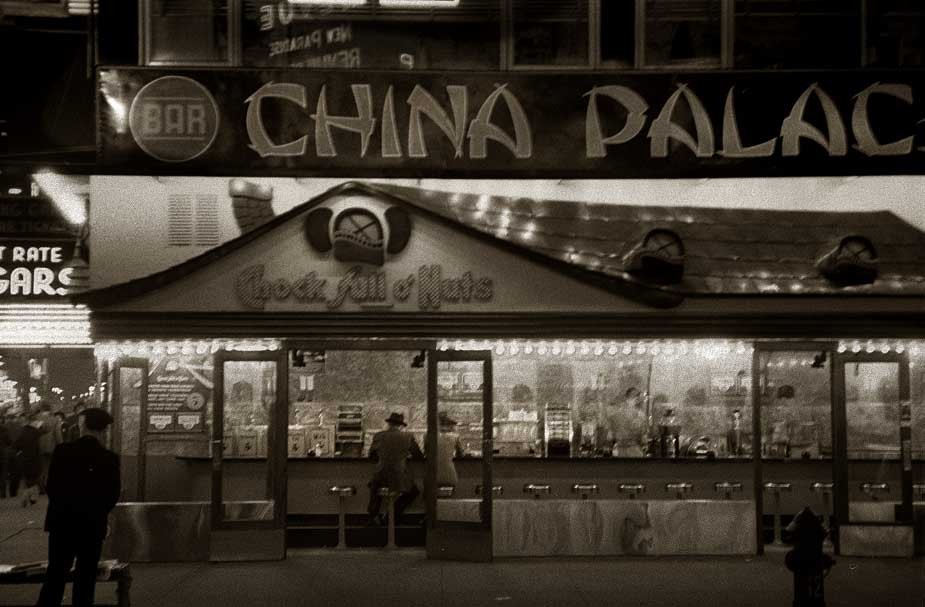

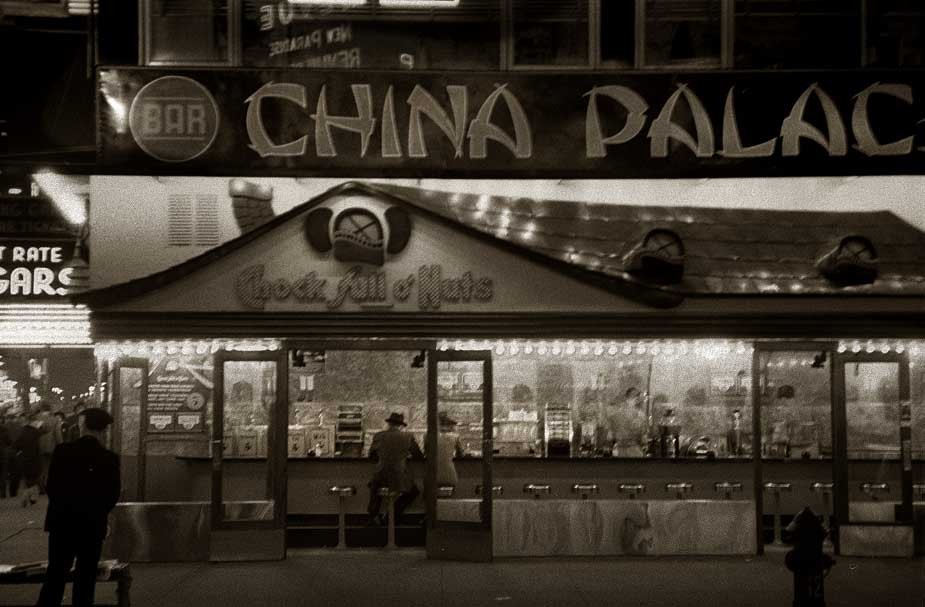

Detail: “Chock Full o’ Nuts at Night”: Laural J. Jones, American: 2004 digital scan taken from ca. 1938-1945 black and white film negative: This nighttime view believed to have been taken in Brooklyn Heights shows the popular post-Depression coffee shop with the large China Palace restaurant behind it. The coffee brand still marketed today featured shops selling a cup of coffee and sandwich for only a nickel. (at the time, there were 18 shops around New York) A police officer looks on at foreground left while a gentleman wearing his hat can be seen seated along a row of stools through the open doorway of the establishment at center. Courtesy: Private Florida Collection

Detail: “Union Rally at Night”: Laural J. Jones, American: 2004 digital scan taken from ca. 1938-1945 black and white film negative: Holding flares and American flags, a nighttime rally of custodians employed by New York City custodians, members of School & Library Employees Local Union 74, takes place at an unknown New York City location. Courtesy: Private Florida Collection

Detail: “Entrance to Luna Park, Coney Island at Night”: Laural J. Jones, American: 2004 digital scan taken from ca. 1938-1945 black and white film negative: Luna Park was an amusement park in Coney Island, Brooklyn, in New York City that first opened in 1903 and was destroyed by fire in 1944. It finally closed in 1946 after a second fire. Courtesy: Private Florida Collection

Taking advantage of city life, while using the Leica 35mm rangefinder to record night scenes a speciality, Laural Jones documented a fascinating and important record of Manhattan and the outer boroughs from the late 1930’s and into the 1940’s, with some of the larger events unfolding before his camera spanning the later years of the American Depression and leading through to the re-ordering of a new world order brought on by World War II. Sadly, the story of preservation as it relates to someones creative and personal artistic endeavors is one consistent with people’s indifference to memories and Photography’s evolving history. But survivors like Laural Jones do show up, thankfully, and in these nine digital offerings, I think you will find plenty to be fascinated with and hopefully inspired by.

David Spencer-

Detail: “Picnic Kiss”: Laural J. Jones, American: 2004 digital scan taken from ca. 1938-1945 black and white film negative. Laying on a blanket shirtless, and with a picnic hamper and two glasses balancing on top at left, the photographer Laural Jones kisses a woman that may be his future spouse Edith at an unknown location. This woman appears in many surviving negatives taken by the photographer, including one of her on the Asbury Park boardwalk at the top of this post. Courtesy: Private Florida Collection