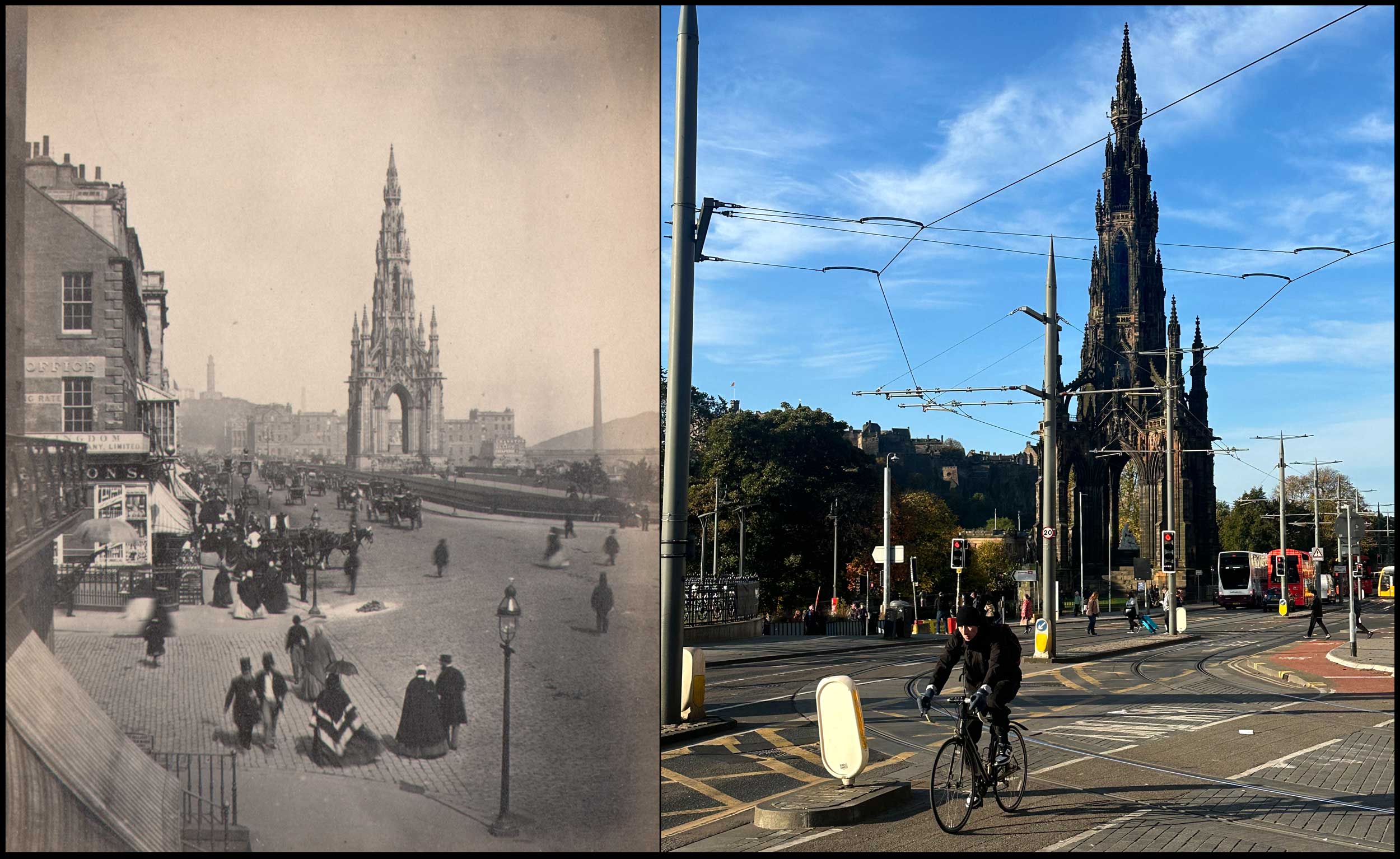

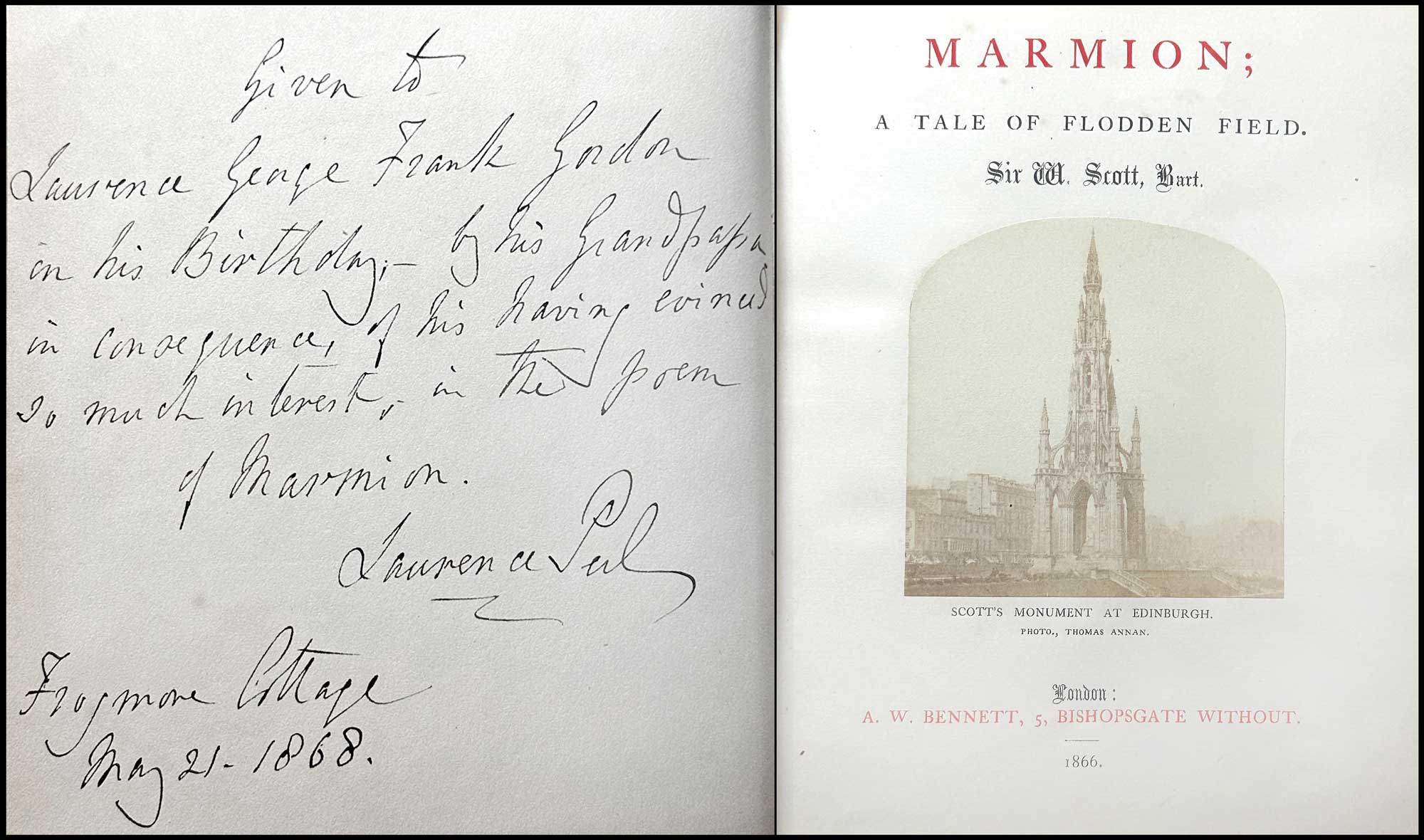

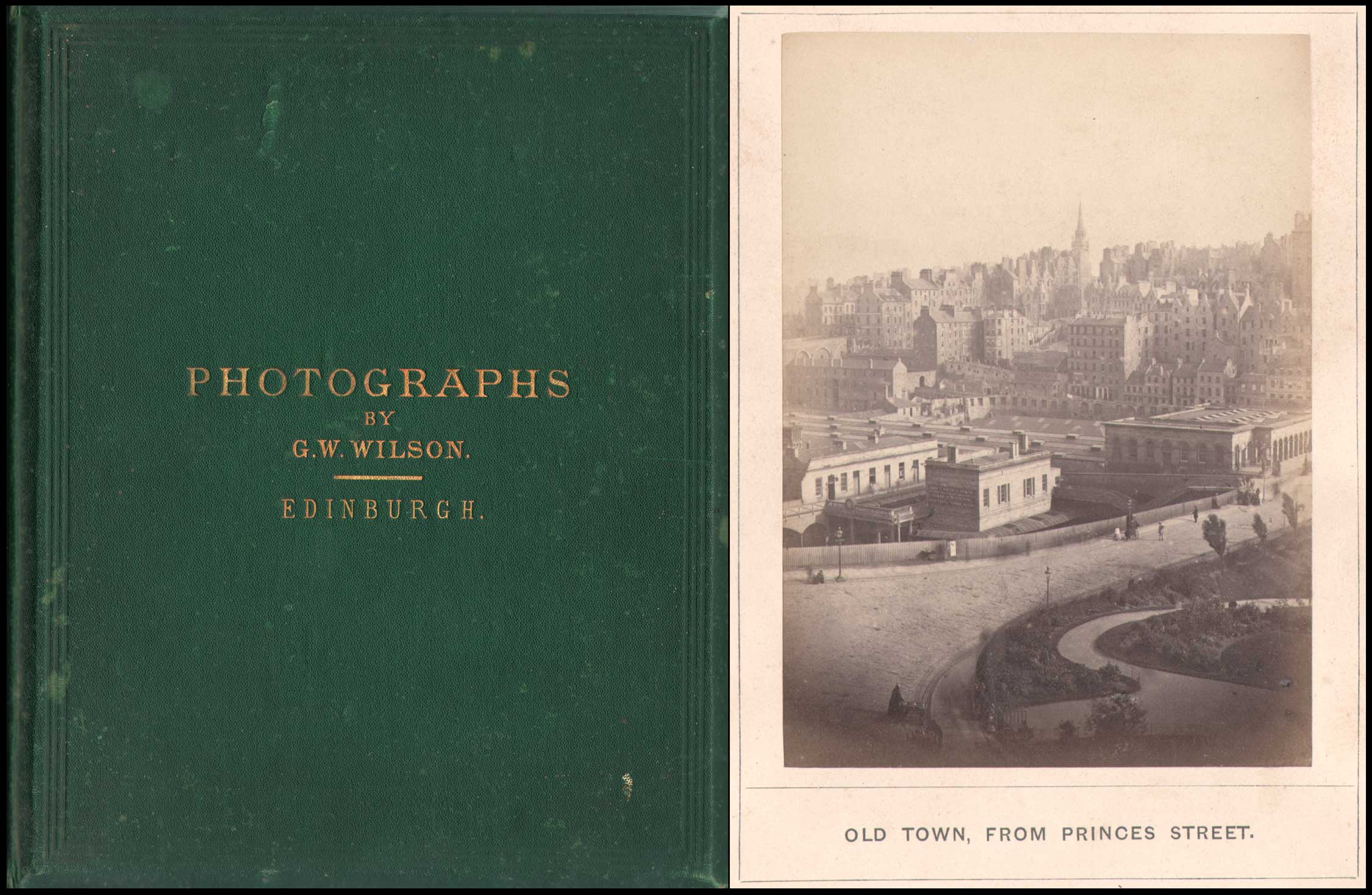

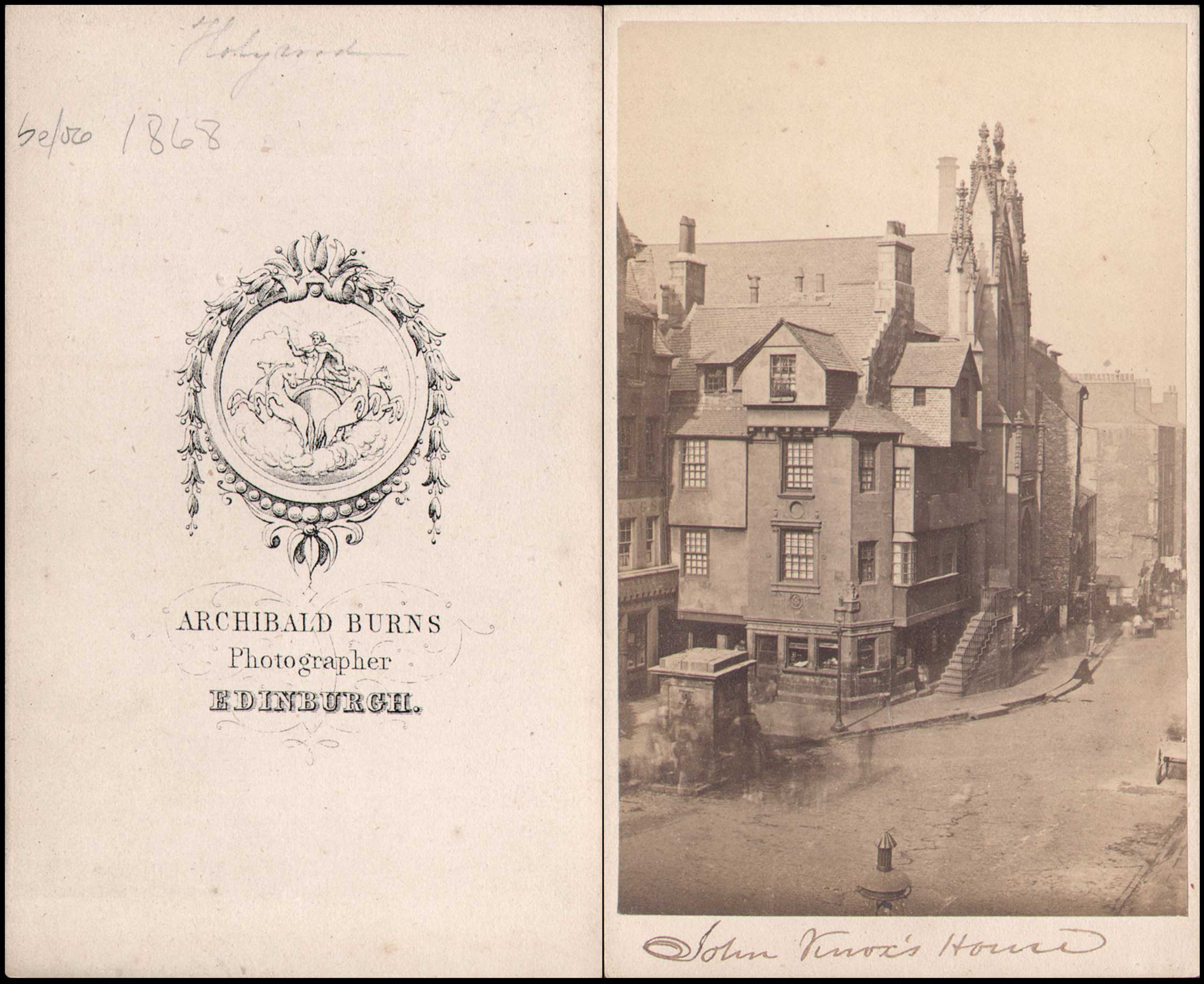

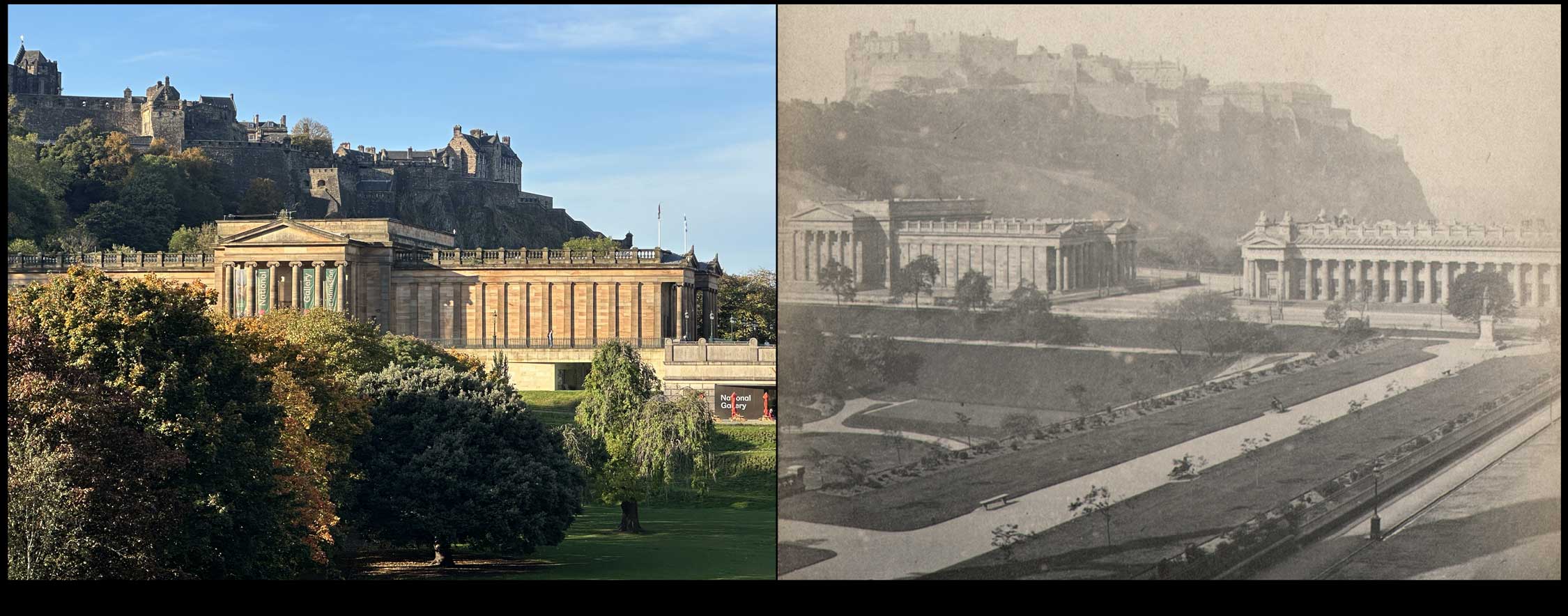

“Coburnesque”, or, in the style of American master pictorialist Alvin Langdon Coburn, (1882-1966) was how the work of now forgotten American photographer Henry Ravell (1864-1930) was described in 1908 by London’s Amateur Photographer & Photographic News.

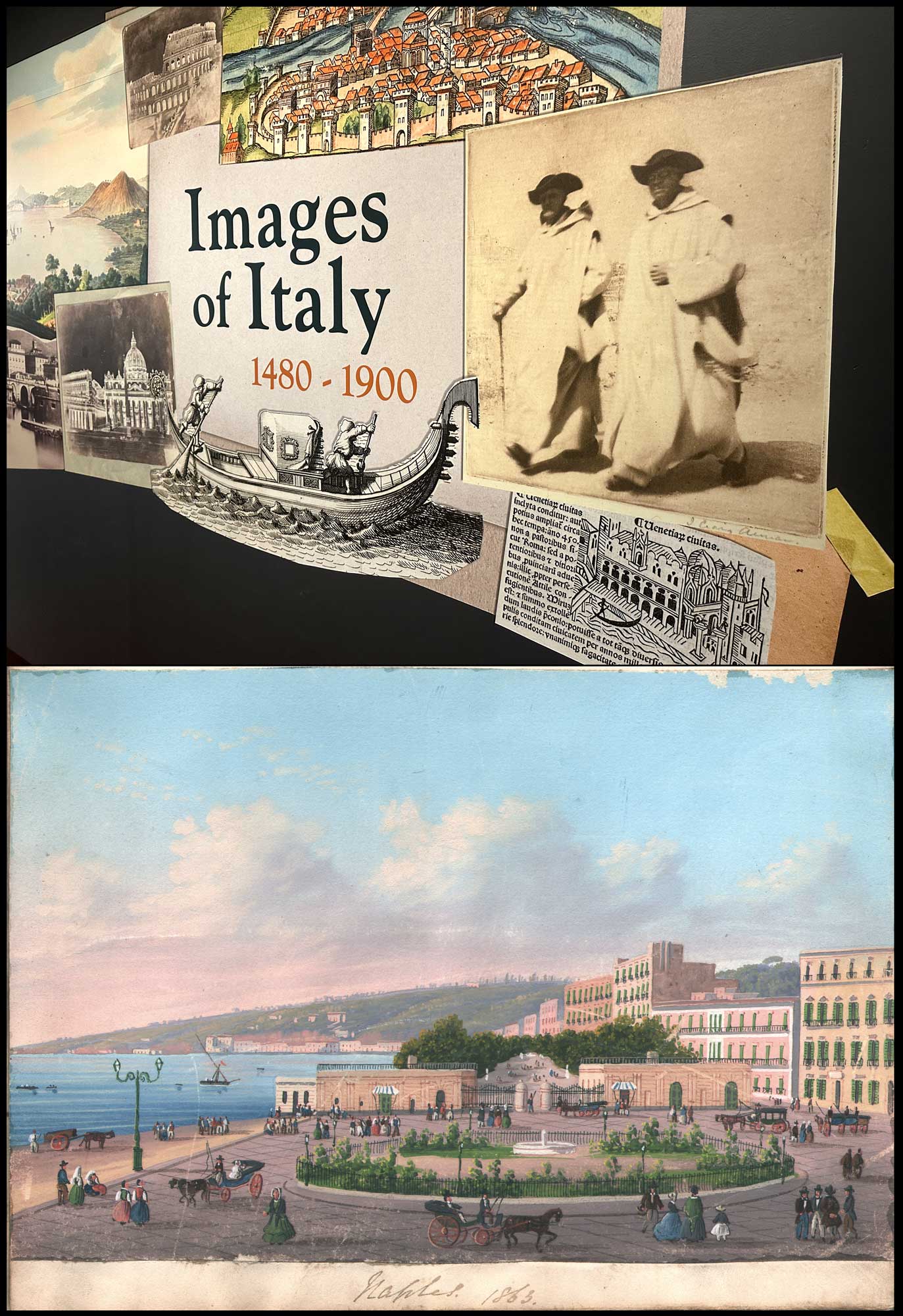

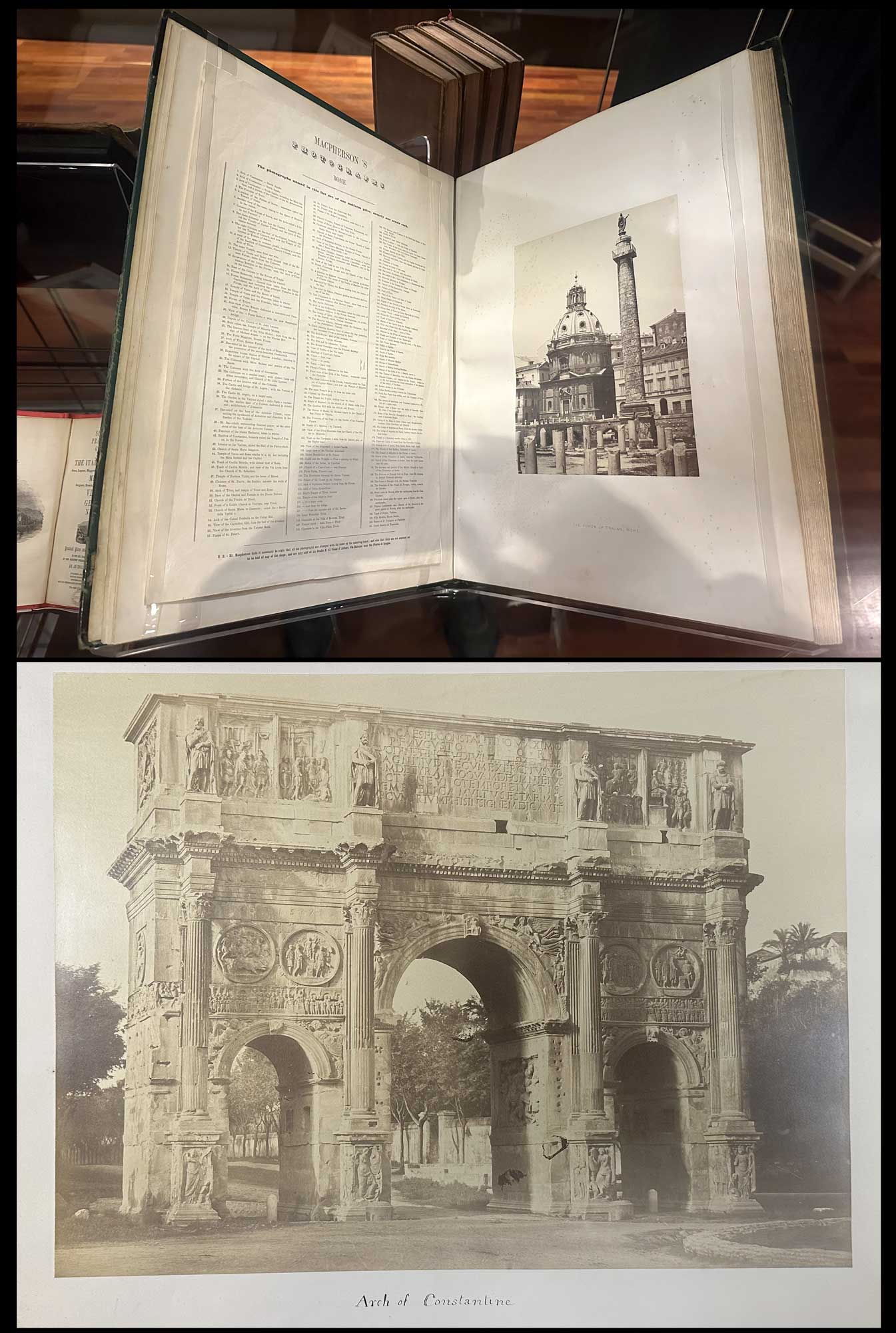

Detail: “A Narrow Street-Guanajuato”: Henry Ravell, American: 1864-1930. Vintage multiple color gum print c. 1907-14. Image: 33.1 x 23.5 presented loose within brown paper folder with overall support dimensions of 39.8 x 58.8 cm. In central Mexico, with the dome of a church framing the skyline at center in background, two native women make their way along one of Guanajuato’s narrow streets. Henry Ravell perfected the gum bichromate process to a very high level. Probably in 1906-07, he began experimenting in multiple color gum. In Germany, around this same time, similar examples were being done by the brothers Theodor (1868-1943) and Oscar Hofmeister, (1871-1937) as well as Heinrich Wilhelm Müller. (1859-1933) From: PhotoSeed Archive

Under the headline “Local Colour.” by journal critic “The Magpie”, a discussion of the merits around Ravell’s new color multiple gum printing process was considered for their large readership. Commenting on a series of his Mexican church photographs published in the May issue of the Century Magazine, “Magpie” writes:

“Who is this Mr. Ravell, and what is his wonderful colour process, which is not “on the negative”? Multiple-gum, one may surmise- and one may also venture to guess that Mr. “de Forest” (Lockwood de Forest- editor) has, notwithstanding this flourish of trumpets, nothing very much to tell us. The Ravell photographs, illustrating “Some Mexican Churches,” are Coburnesque, and the pictures are, in their very Yankee style, fine and strong- which is more than can be said for those in our English monthlies. Couldn’t Mr. Ravell be induced to send some examples of his work to the R.P.S. or Salon? We badly need some new American exhibitors.” (June 16, p. 600)

A reassessment of Ravell’s output is long overdue in elevating him back to his rightful position as one of the more important practitioners of pictorialism in the early 20th Century canon of American artistic photographers.

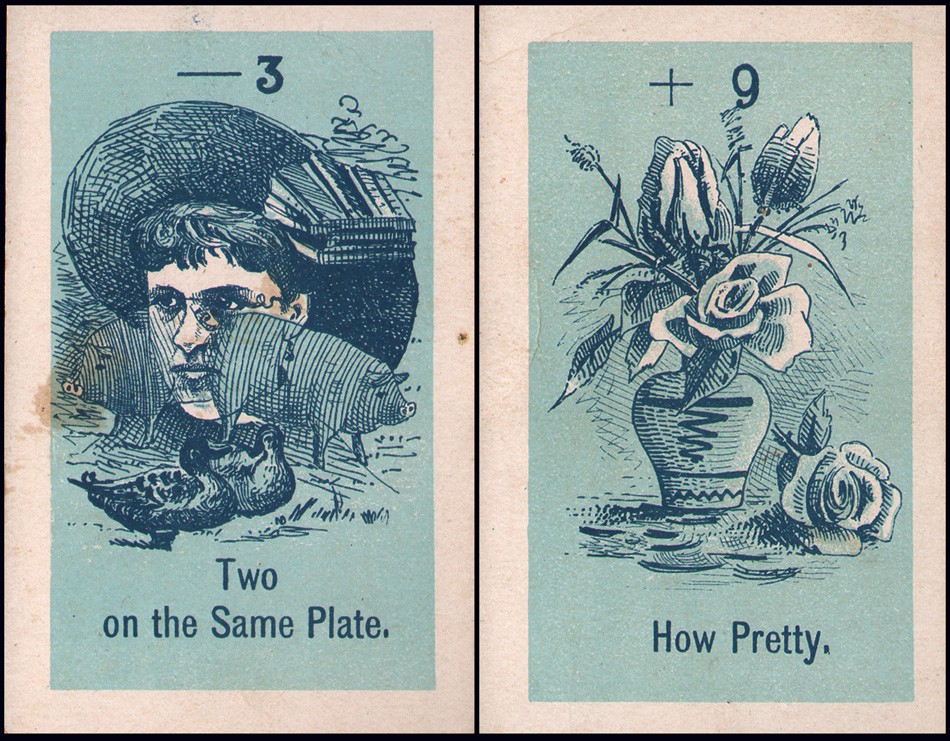

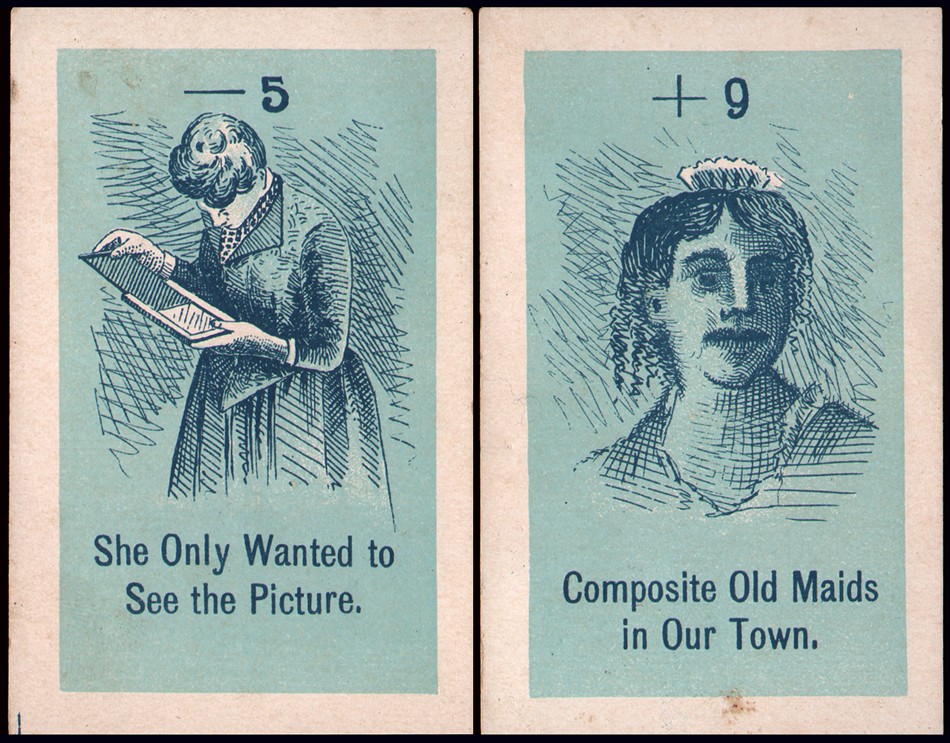

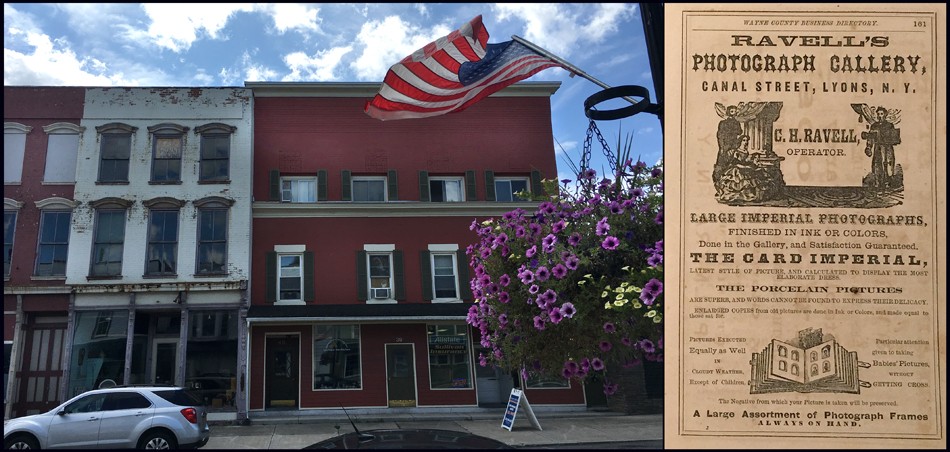

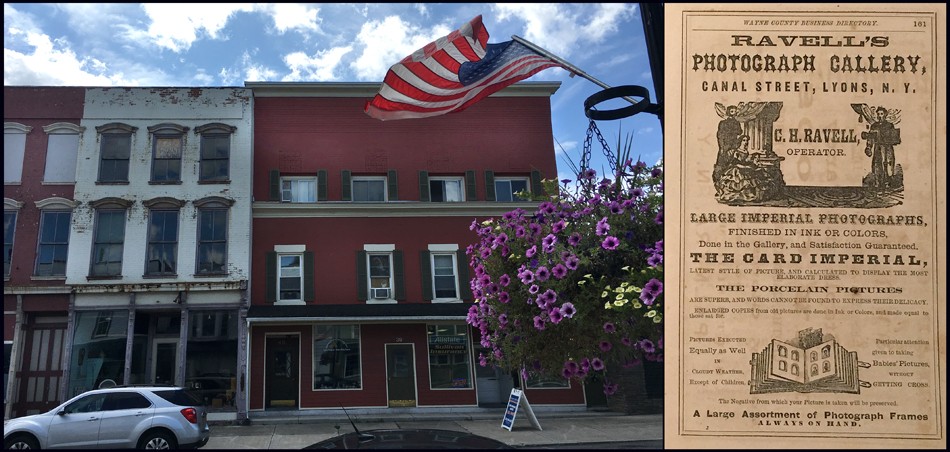

Left: Henry Ravell was only a toddler when his father Charles Henry Ravell (1833-1917) opened a skylight photographic studio on the third floor of this brick building painted red located on Canal Street in Lyons, New York around 1865-66. Shown here in the summer of 2019, the entrance was at the present day 36 Canal street (on the far right of the photo-presently an insurance office) but was numbered #30 Canal before the turn of the 20th Century. It was here that Henry was “brought up in photography from childhood and became an expert in all processes before he was twelve years old”. Right: A full-page advertisement for “Ravell’s Photograph Gallery” operated by C.H. Ravell at the Canal street building appeared in the 1867-68 Wayne County (New York) Business Directory. At the time, Charles Ravell would have been using the wet-plate process, and the ad highlights “Large Imperial Photographs finished in Ink or Colors”… “Pictures Executed Equally as Well in Cloudy Weather Except of Children”… “Particular attention given to taking Babies’ Pictures, without Getting Cross”. Left: David Spencer for PhotoSeed Archive; Right: courtesy Museum of Wayne County History.

Undoubtedly, “Magpie” would have been pleased to know Henry Ravell sprung from fine English photographic stock. His father Charles Henry Ravell (1833-1917) emigrated to the U.S. from Boston, England and was known to have been active as a Daguerreotypist as early as 1857, (1.) his trade shingle set up early in the New York state village of Chittenango. By 1860, U.S. Census records show he had moved to Wolcott, New York, where he was a commercial photographer. Surviving cdv photographs from here bearing his C.H. Ravell back-stamp reveal some of his clients were young men heading off to fight in the American Civil War.

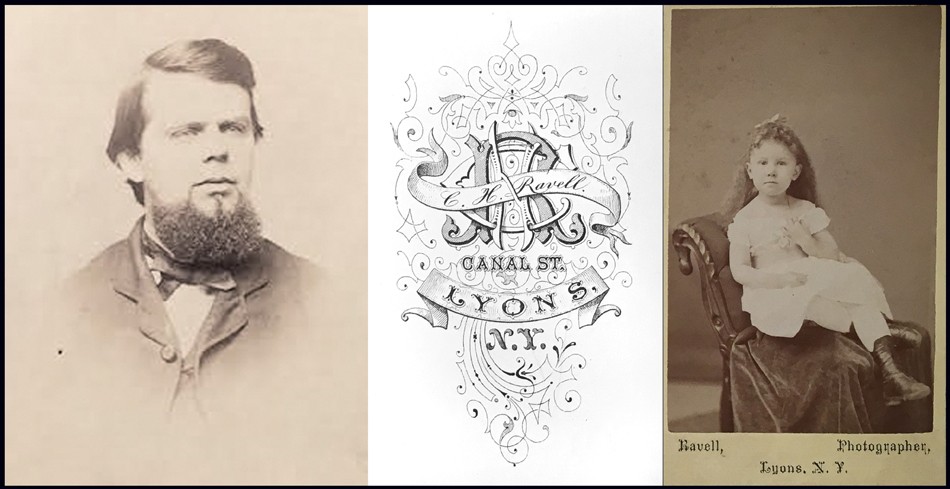

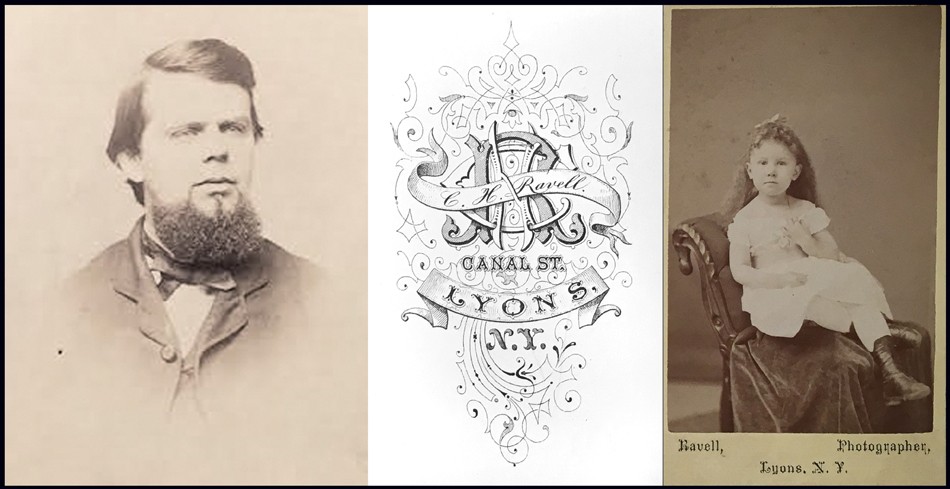

Left: This is the only known portrait of commercial portrait photographer Charles Henry Ravell, father of Henry Ravell. The carte de visite albumen portrait shows him most likely in his early 30’s, after he had settled in Lyons, New York. Born Charles Herring Ravel in Boston, England, he emigrated to the U.S. as a young man, with an early notice of his Daguerreotypist skills from 1857 showing he was living in Chittenango, New York State. By 1860, he had settled in Wolcott, where son Henry was born in early 1864. By 1867 or earlier, he and wife Cornelia Dudley Ravell (1840-1908) and Henry had moved permanently to nearby Lyons. Middle & Right: This elaborate backstamp engraving for C.H. Ravell’s Canal Street skylight studio in Lyons is ca. 1865-80, with the albumen portrait subject (Right) a young girl posing on a commercially available chair. Both: courtesy Museum of Wayne County History

Born in early January of 1864 in Wolcott, Henry Ravell is known to have embraced photography from a very young age. As a boy, he became his father’s apprentice. Lockwood de Forest, (1850-1932) an important influence on Henry for the rest of his life in the 20th Century and important American painter and furniture designer, wrote in 1908 that Henry:

“was born and brought up in photography from childhood and became an expert in all processes before he was twelve years old.” Through a fascinating confluence of sons starting out in their father’s professions, Henry Ravell graduated to having an interest in art, and he studied water-color painting with the noted American artist and Tonalist Henry Ward Ranger, (1858-1916) probably in his late teens or early 20’s. The artist and student had much in common. Like Charles Henry Ravell, who had established his own Canal Street photo studio in Lyons, N.Y. by 1867, (Wayne County Business Directory) Ranger’s father Ward Valencourt Ranger (1835–1905) had opened his own commercial studio in 1868 in Syracuse, N.Y., 55 miles east of Lyons, almost at the same time. Like Henry Ravell working for his father at an early age, Henry Ranger was also known to have worked in his father’s establishment as a young man.

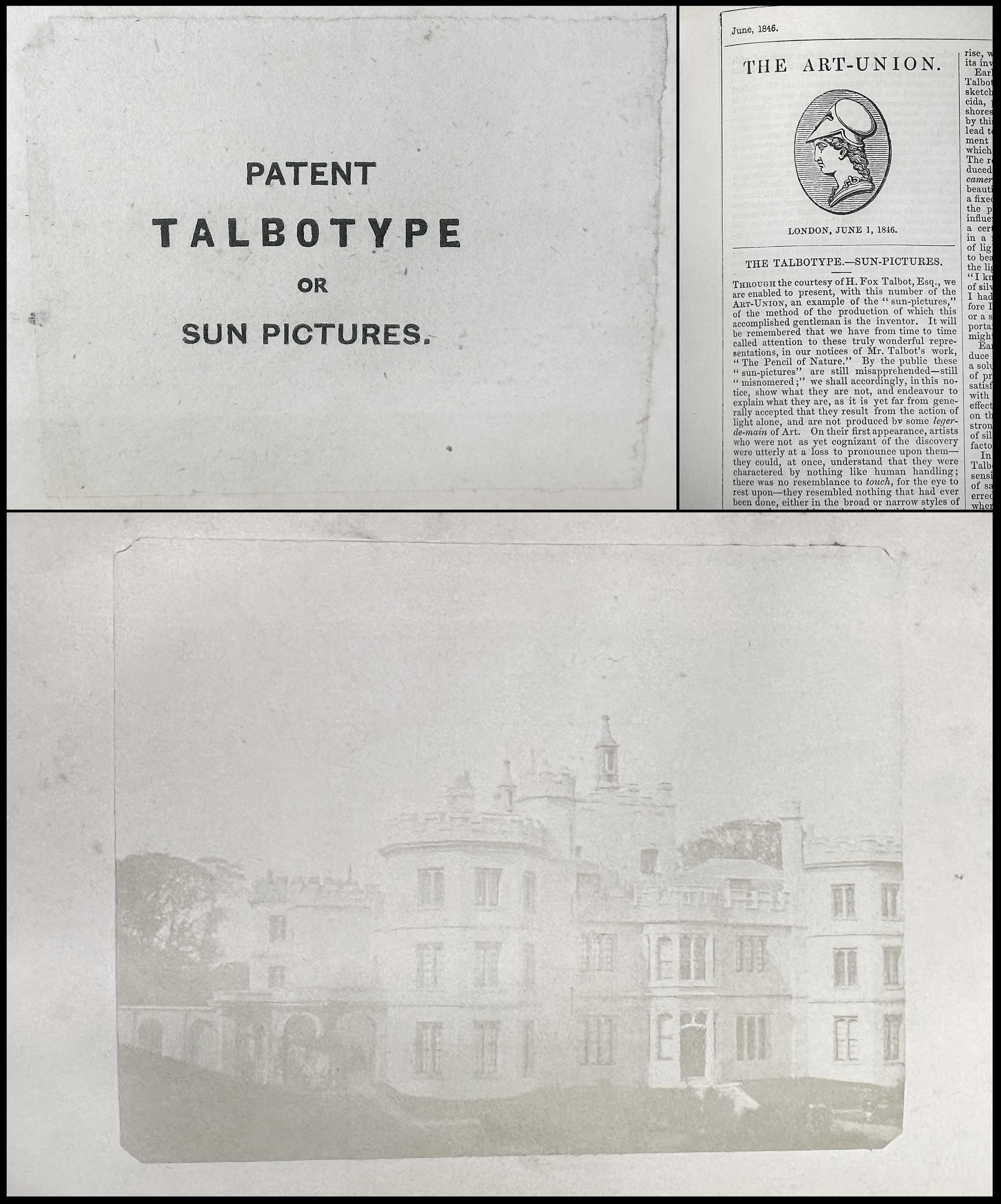

Upper Left: “Negative Outline-Dark Chamber”: woodcut from 1892 volume “Crayon Portraiture: Complete Instructions for making Crayon Portraits on Crayon Paper and on Platinum, Silver, and Bromide Enlargements” by J.A. Barhydt. In the early 1880’s, Henry Ravell worked in a similar capacity as the artist shown here for the Photo-Copying House Ten Eyck & Co. of Auburn, New York. Woodcut shows an enlarged and enhanced crayon portrait being made freehand on the easel at right. A photographic negative from a sitter has been placed inside a large box camera at left while mounted in front of a scrimmed-off window. This provides the light source for the projection within a darkened room while the artist goes over the outline and shadow lines of the projection in a first step. Other variations of crayon portraits began with an artist working in a lighted studio with charcoal and pastels after the initial projected outline on crayon, gelatin, bromide, etc. papers had been chemically fixed. Ten Eyck advertised on cover stationary from 1884: “Fine Portraits in India Ink, Water Colors and Crayon, By the Association of Celebrated Portrait Artists…” (From: Internet Archive) Lower Left: December, 1884 postmarked cover (envelope) from Ten Eyck & Co. Portraits located at 108 Genesee St., Auburn, N.Y. (8.5 x 15.0 cm-right margin perished) Ravell worked at the firm about this time, making a living combining his skill of photography and art. In the late 1880’s to early 1890’s, he became an agent for Ten Eyck after moving to Mexico. From: PhotoSeed Archive. Right: “Crayon-style Portrait” ca. 1890-5: (50.9 x 40.5 cm) enhanced water-color or India inks applied by hand to unknown (bromide?) photographic emulsion fixed onto light grade cardboard matrix. Henry Ravell produced similar crayon-style portraits for Ten Eyck, with this example from an unknown artist featuring Mary Carruthers Tucker (1877-1940) as subject, then living in Provo-City Utah. She was the spouse of C.R. Tucker, whose work is featured at PhotoSeed. From: PhotoSeed Archive

Sometime in the early 1880’s after Henry had finished this “apprenticeship”, he moved to nearby Auburn, New York, about halfway to Syracuse from Lyons, to a job crafting Crayon and Pastel portrait photographic enlargements for Ten Eyck & Co. At the time, this firm is said to have been the largest of its’ type in the world. This gave Henry additional artistic skills, combining his interest in photography and art, an important and influential confluence indeed. He kept at this profession until either 1883, according to Lockwood de Forest, or as late as 1892, in a posthumous biography of Henry by sister Florence.

“Portrait of John Lee Cole”: Henry Ravell, American: 1864-1930. Ca. 1885 Gouache and or Oil? on paper, mounted within period wood frame bearing inscription “John L. Cole to Jason Parker, 1918”. This very rare example of a surviving painting by photographer Henry Ravell is now owned by the Museum of Wayne County History in Lyons, New York. Cole was a 1859 graduate of Yale and grandson of the Rev. John Cole, a founder with John Wesley of the Methodist Church in the U.S.. In 1862 he was admitted to the bar and later became a banker in Lyons for Mirick & Cole. An earlier 1882 notice of Henry’s artistic pursuits was published in The Democrat and Chronicle newspaper of Rochester, New York: “Henry Ravell, of Lyons, was in this city last night, on his return from Medina, (New York-editor) where he disposed of two of his latest paintings for $70.” (November 26) Photo by David Spencer for PhotoSeed Archive- artwork courtesy Museum of Wayne County History, Lyons N.Y.

At this time, Henry is said to have moved to Cuernavava Mexico, south of Mexico City, where he became a far-flung agent for the Ten Eyck & Co. firm, although a certain amount of traveling back and forth to the U.S. and the family home was probably the reality. To wit, the Minnesota State Census for 1895 lists his occupation as “artist”, claiming an American residence while living with his father, mother and younger brother, Charles Ravell Jr. in the city of St. Paul. Here his father finished out his career running a photo studio on Western Ave. from 1890-92.

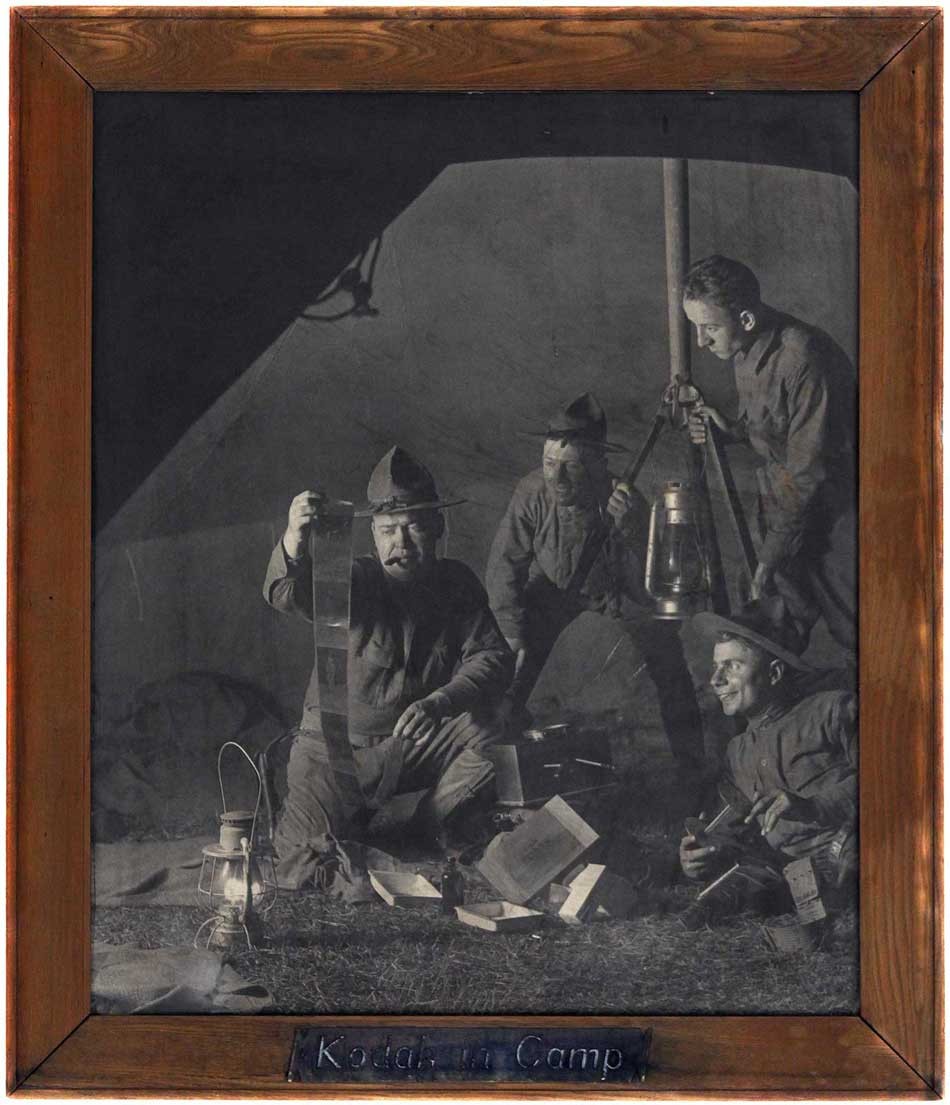

During the mid 1880’s back in Lyons, a fascinating yet presently unsubstantiated account of Henry’s involvement with the development of the first Kodak camera is relevant for background on his future career as a master photographer who became a striver with his own agenda. This event is worthy of historical contemplation in the present from reminisces provided in the aforementioned posthumous biography published in 1940:

“George Eastman of Rochester, New York, was a family friend. During a visit of three or four weeks, Mr. Eastman worked on and developed his famous Kodak, with the help of my father and brother.” “Their workshop was the basement of our former home at 70 Broad Street, Lyons. Mr. Eastman offered my father stock in the Kodak Company, which he often regretted not accepting.” (2.)

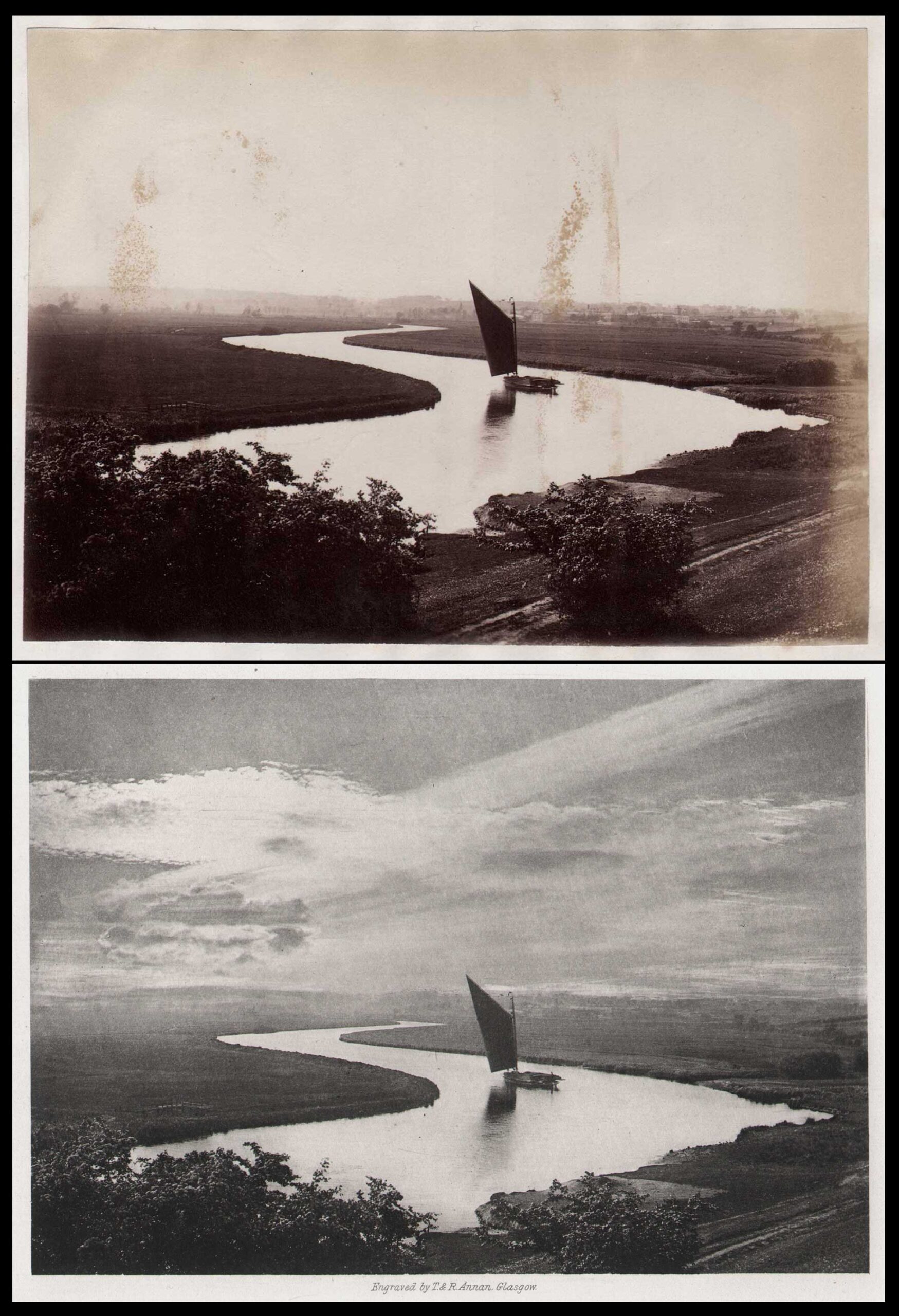

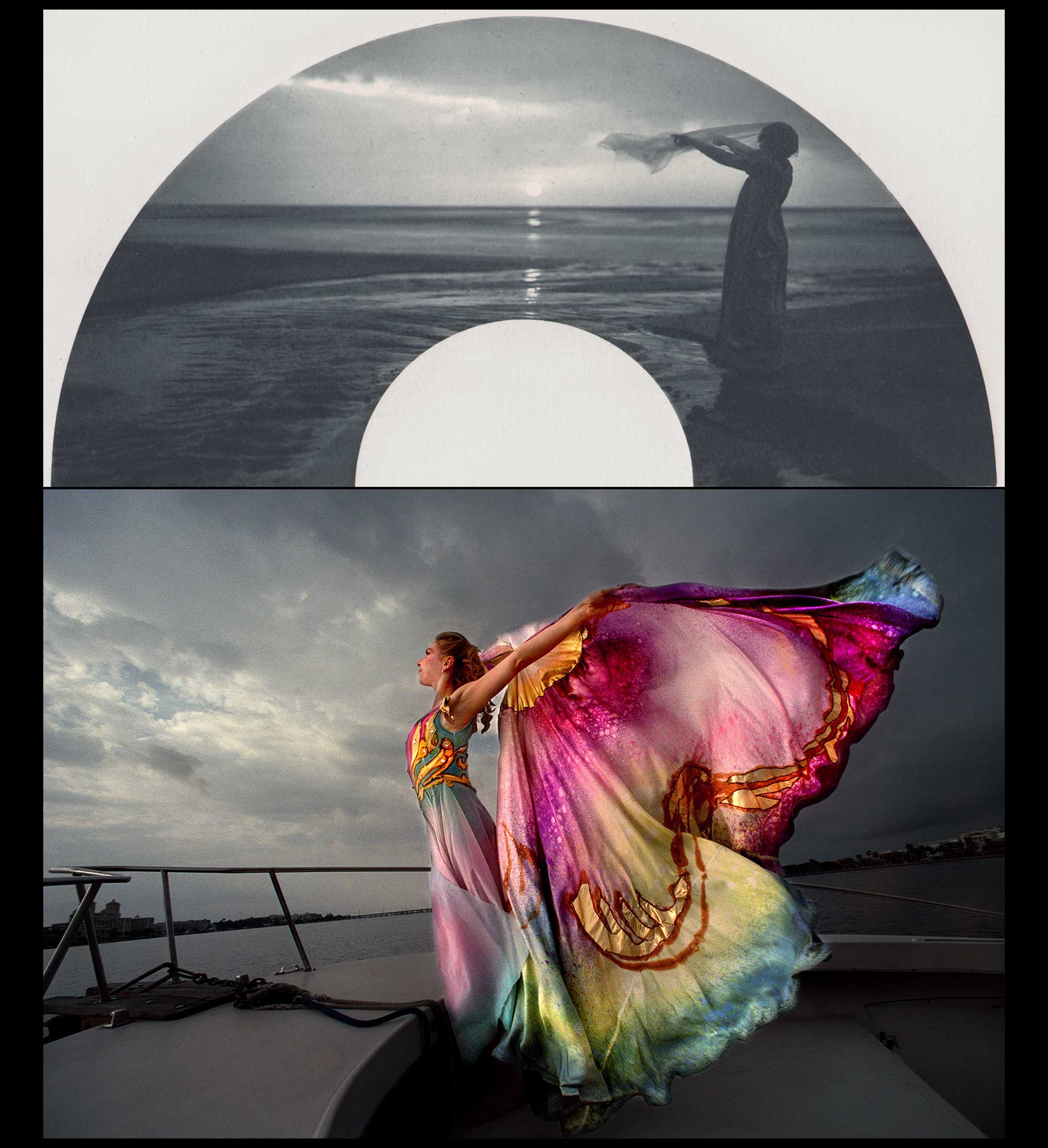

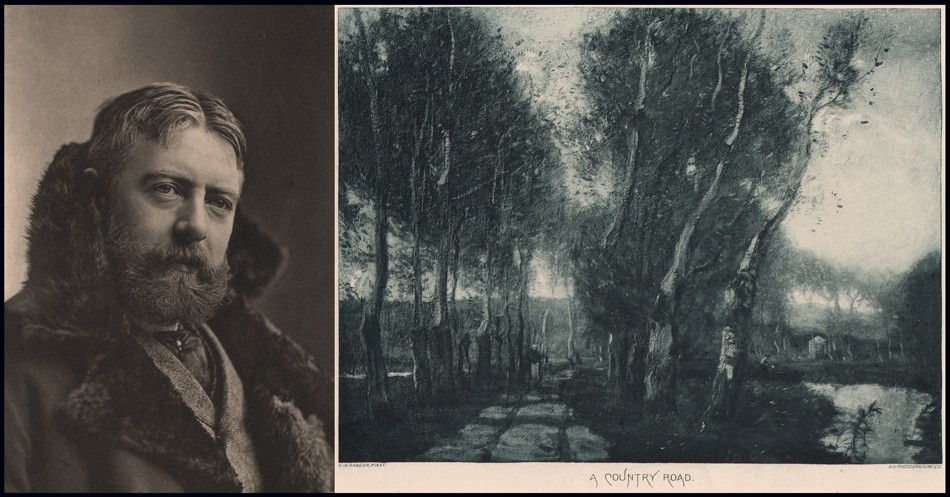

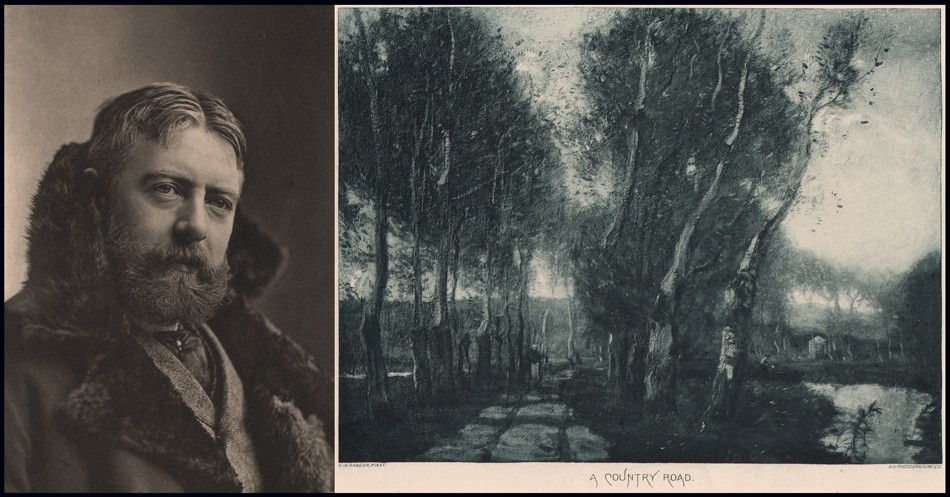

Left: “H.W. Ranger” (Henry Ward Ranger): Napoleon Sarony, American: born Quebec. (1821-1896) Photogravure published in periodical “Sun & Shade”: New York: May, 1894: whole #69: N.Y. Photo-Gravure Co.: 22.4 x 15.2 | 34.9 x 27.6 cm. Like Henry Ravell assisting in his father’s studio, American artist and Tonalist Henry Ward Ranger (1858-1916) worked in his own father’s studio as a young man. Later, Ranger taught Henry water-color painting, probably when Ravell was in his late teens or early 20’s. The “Sun & Shade” periodical noting of Ranger: “His work in Lower Canada won him great repute, and as a water-color painter, before taking to oil-painting, he was undeniably excellent.” Right: “A Country Road”: Henry Ward Ranger, American. (1858-1916) Photogravure published in periodical “Sun & Shade”: New York: May, 1894: whole #69: N.Y. Photo-Gravure Co.: 17.1 x 22.7 | 27.6 x 34.9 cm. Ranger’s bucolic painting style reveals itself in this simple country scene of a roadway lined with trees, probably done in Holland. Scenes like this would have undoubtedly made an impression on Henry the fledgling art student, assuming he had access to reproductions or the originals of his teacher’s work. On Ranger in the periodical: “He is an admirer and follower of the best Dutch school of art, and has made it his pleasure and his duty to pay many visits to Holland, in order to be perfectly au fait with the excellencies of its best masters.” On “A Country Road”: “It is seldom that so simple a subject becomes so important in form and color-so full of air and freedom, and so admirably harmonious in its proportions.” Both from: PhotoSeed Archive

Memories can sometimes be suspect, but several details of Florence’s biography are important and worth following up on, with this website happy to accept the challenge. By tracking down old street addresses, the Ravell family home as published in the 1886-87 Lyons residential directory was actually found to be located as 40 Broad Street. (William Smith, whose occupation was Express Transfer Agent, lived at 70 Broad St. as published in the same directory) Coupled with the knowledge that Lyons street addresses had been renumbered, probably in the early 20th Century, and cross-referencing with a 1904 Sanborn Fire Insurance Company map found online at the Library of Congress, the former and still standing Ravell home built in 1850 revealed itself to be the present day 64 Broad Street. All of this effort, if somehow confirming a claim George Eastman had actually spent time in Lyons was true, could result in a potentially fascinating footnote to the development of one of the most important inventions of the 19th Century- The Kodak No. 1 Camera which debuted in 1888: “By far the most significant event in the history of amateur photography”, according to the Met Museum in New York City.

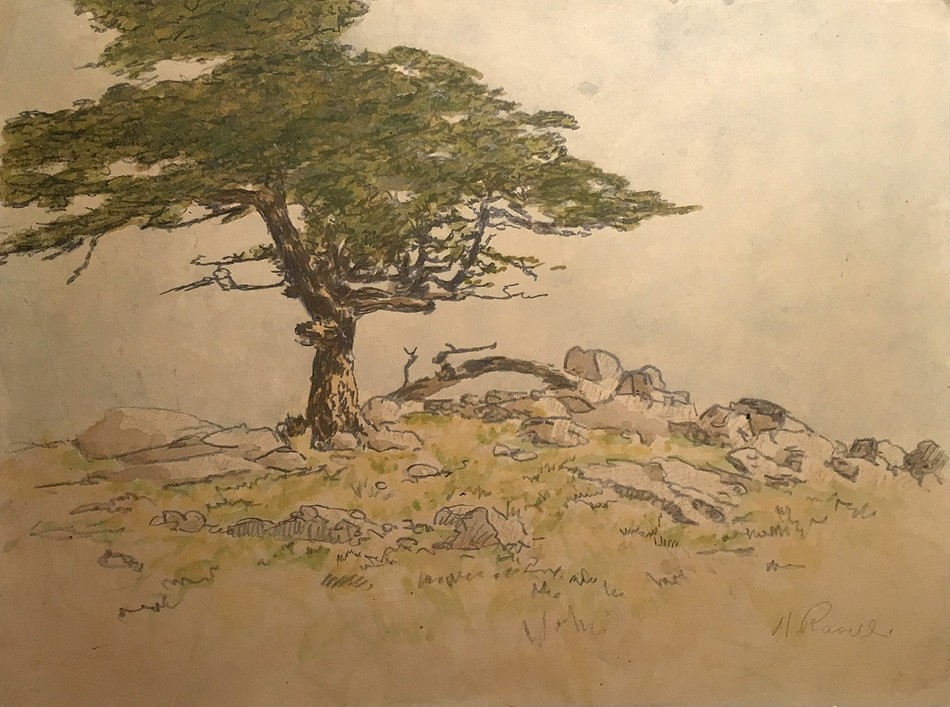

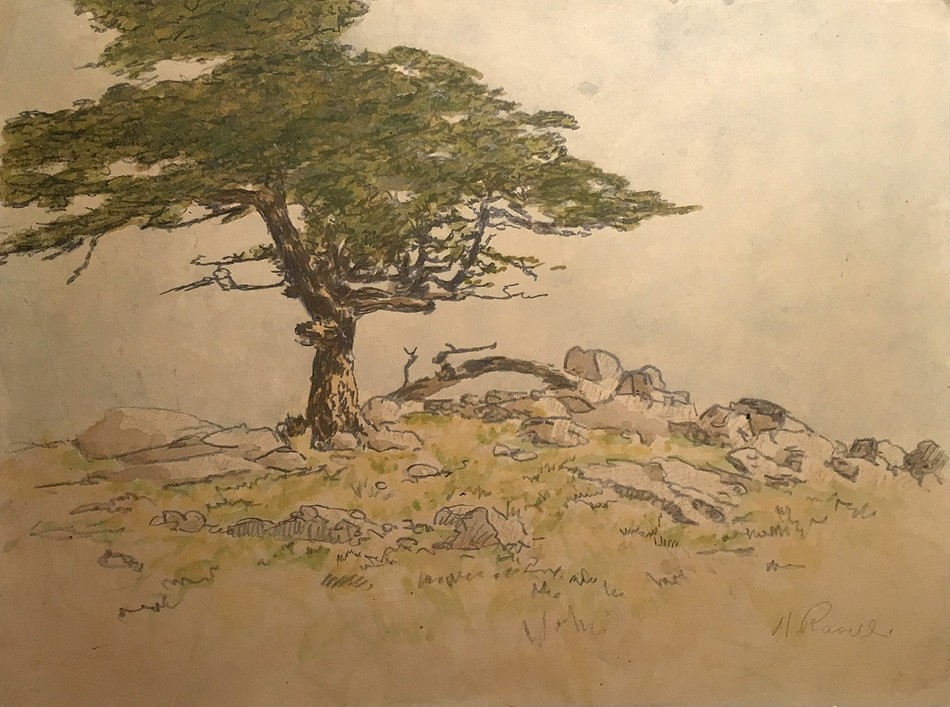

“Cypress Tree -Pebble Beach”: Henry Ravell, American: 1864-1930. Vintage watercolor drawing on paper: ca. 1915-20. (Museum of Wayne County History accession #Pi 176f with verso sticker additionally listing number 148 and $30.00) One of the few known examples of a watercolor drawing by Ravell is this delicate landscape featuring a lone cypress tree springing from a rock outcropping in Pebble Beach on California’s Monterey Peninsula. It may depict the world famous “Lone Cypress”, an approximately 250 year-old Monterey Cypress standing today on a granite hillside off the famed 17-Mile Drive. Courtesy: Museum of Wayne County History, Lyons N.Y.

This panel reveals the artistic styles of two distinct artists signing their work nearly identically. It’s presented with the hope a distinction can be made for a larger audience. The reality at present: nearly every painting returned on web searches is misattributed to being by photographer/artist Henry Ravell. Left Diptych: Top: “Cypress Trees at Pebble Beach”: Henry Ravell, American: 1864-1930. Vintage watercolor drawing on paper: ca. 1915-20. (Museum of Wayne County History accession #Pi 176e with verso sticker additionally listing number 147 and $20.00) This is one of three rare watercolor drawings by Ravell. Showing a stand of cypress trees in Pebble Beach on California’s Monterey Peninsula, the signature of “H.Ravell” in graphite has been enlarged in separate bottom panel. Courtesy: Museum of Wayne County History. Right Diptych: Top: “The Ripers” (The Reapers): Henry Etienne Ravel, American, born Naples Italy to French citizens. (1872-1962) Oil on artists board: ca. 1946: 20.5 x 15.4 presented within wood frame (not shown) 24.5 x 19.4 x 2.0 cm. Two field workers harvest wheat, a small landscape most likely depicting the Italian countryside. Henry Ravel immigrated to America in 1906 and became a naturalized US citizen in 1920. A transportation clerk by trade in the early 1920’s, his paintings- many done in Europe- date from ca. 1930’s-1950’s. Enlarged signature at bottom panel: “H. Ravel”. From: PhotoSeed Archive

The earliest published references to Ravell’s photographic work in the popular press is found around 1905, when Boston’s Photo-Era, writing for their December issue, pronounces him “A new star of the first magnitude”, although noting his two pictures: “Pleasant Valley” and “Viga Canal”, “do not represent him at his best.” This assessment also including listing him on the journal’s noteworthy list of exhibitors whose work had been accepted for the Second American Photographic Salon which ran from 1905-06.

Upper Left: This quote by Henry Ravell’s older sister Florence Ravell Lothrop appeared in The Lyons Republican & Clyde Times on March 21, 1940 stating Henry and their father Charles Henry Ravell had worked with a young George Eastman in developing the world’s first Kodak camera from 1888 in the basement workshop of their Lyons home. Clipping courtesy Museum of Wayne County History. Lower Left: An original Kodak No. 1 camera from 1888 shown with its lens cap and original documents appeared as Lot 0238 and sold by Auction Team Breker of Cologne, Germany on September 30, 2006. The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York states: “By far the most significant event in the history of amateur photography was the introduction of the Kodak #1 camera in 1888. Invented and marketed by George Eastman (1854–1932), a former bank clerk from Rochester, New York, the Kodak was a simple box camera that came loaded with a 100-exposure roll of film”. Courtesy Auction Team Breker. Far Right: Built in 1850, the former Ravell family home in Lyons, New York was actually located at 64 Broad Street-seen here: not 70 Broad Street as stated in the clipping. The actual address was confirmed by this website using Sanborn fire insurance maps and a Lyons residential street directory from 1886-7. Home exterior courtesy 2018 online real estate sales listing.

Florence Ravell, quoting Lockwood de Forest for her 1940 article on Henry, expanded on her brothers new found respect in the profession, particularly in his mastery of the gum print, which would soon establish him as a major talent:

“Henry Ravell was recognized as one of the leading artists in his profession, both in this country and in Europe where he had exhibited, and has been a contributor to many of the photographic magazines, where a description of his technical processes are given. He succeeded in making a gum print in one printing with results far beyond the finest etchings and very similar in character.”

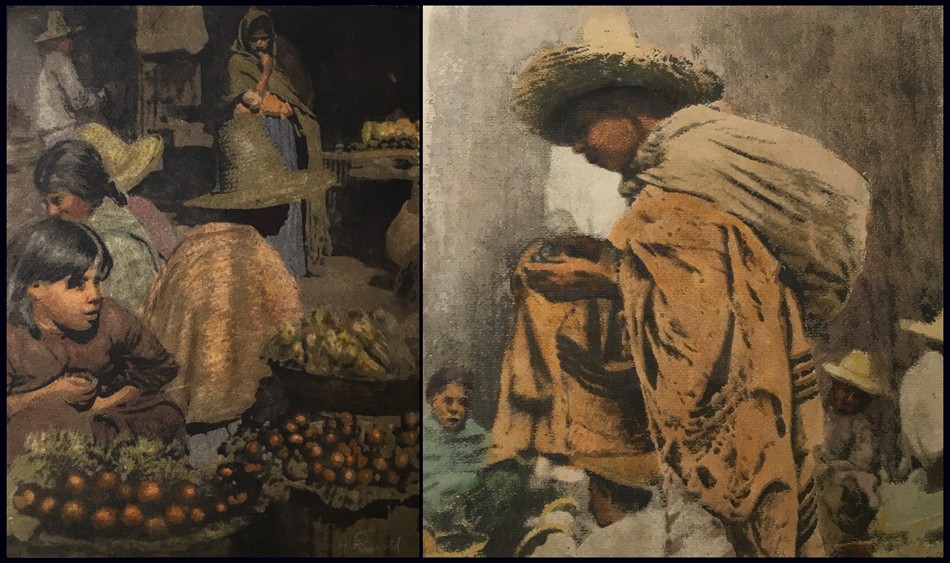

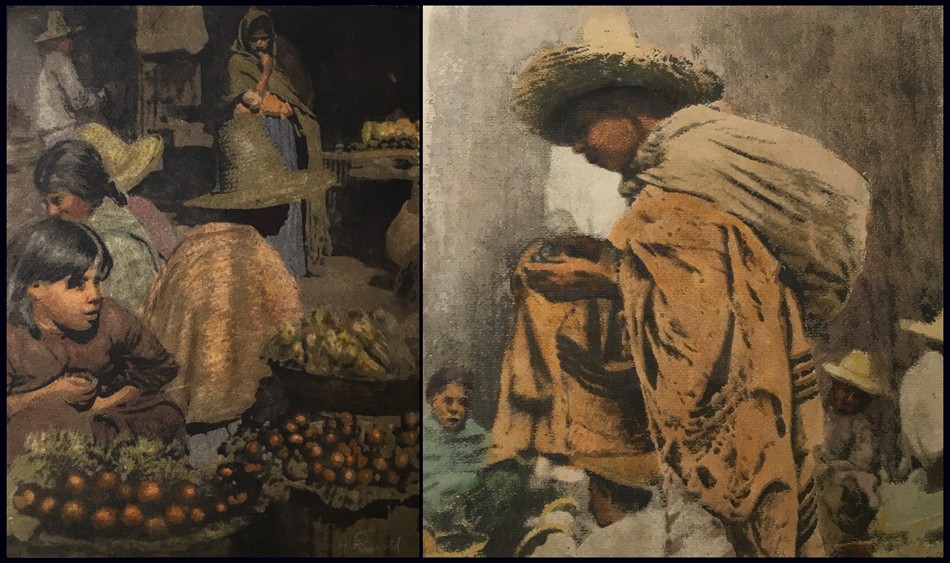

Left: “Mexican Peon”: Henry Ravell, American: 1864-1930. Vintage gum print ca. 1900-15. Alternately titled “A Mexican Peon” as listed in the catalogue of a 1978 retrospective of the artist at the Museum of Wayne County History, although an uncropped variant titled “Mexican Charro” (Mexican Cowboy)- is a more accurate description based on his fancily embroidered sombrero- is held by the California Museum of Photography, Riverside. Right: “Eating Tent-Taxco, Mexico”: Henry Ravell, American: 1864-1930. Vintage gum print ca. 1900-15. These photographs are part of a grouping of 18 singular gum prints featuring Mexican scenes and subjects held in the collection of the Museum of Wayne County History, Lyons N.Y.

Henry perfected the gum bichromate process to a very high level. Probably in 1906-07, he began experimenting in multiple color gum. In Germany, around this same time, similar examples were being done by the brothers Theodor (1868-1943) and Oscar Hofmeister, (1871-1937) as well as Heinrich Wilhelm Müller (1859-1933) (3.) The following quote in the December,1908 issue of Boston’s Photo-Era encapsulates the admiration these gum prints received:

“It will be remembered that last summer Henry Ravell, of Mexico, exhibited in New York and Boston his results in multiple gum-bichromate printing in color. They excited considerable interest at the time, especially among our painters, who were very cordial in their praise of Mr. Ravell’s beautiful work, for it showed, in an eminent degree, the artistic possibilities of the gum-process.” (p. 300)

Left: “Chapel of the Holy Well near Mexico City”: Henry Ravell, American: 1864-1930. Vintage gum print ca. 1900-15. Right: “Church, Mexico”: Henry Ravell, American: 1864-1930. Vintage gum print ca. 1900-15. Museum of Wayne County History accession #Pi 176p with verso sticker additionally listing number 2 and $5.00) Featuring church architecture, these are part of a grouping of 18 singular gum prints of Mexican scenes and subjects held in the collection of the Museum of Wayne County History, Lyons N.Y.

Again writing in 1940, Florence wrote of her younger brother: “but his favorite work was photography, and the gum print process. This process was original with an Austrian who refused to make it known, but Henry experimented until he developed it, and later gave the formula to the world.” The conjecture of this website is the possibility Henry originally gleaned and modified his own multiple gum color process from the earlier work of Austrian photographer Heinrich Kühn. (1866-1944) An 1897 example of a three-color gum print by him can be found in the collection of the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe in Hamburg Germany.

Left: “Mexican Vegetable Seller”: Henry Ravell, American: 1864-1930. Vintage multiple color gum print c. 1907-14. Right: “Mexican Youth”: Henry Ravell, American: 1864-1930. Vintage multiple color gum print c. 1907-14. These are two of the three rare multiple color gum prints by Henry Ravell held in the collection of the Museum of Wayne County History, Lyons N.Y.

In 1908, Henry’s champion Lockwood de Forest gave a fuller explanation of the technical details for this color process, as part of copy included with a series of Mexican Church studies published in the May issue of the Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine:

“Last summer he started experiments in color-printing. His process is simple. Instead of introducing colors on the negatives, as in the lumière process, he is using the colors in the sensitizer of the printing paper. The specimens he has sent me are printed in three or four colors. Each print is finished, recoated all over with the sensitizer with the next color, and again printed. This is done for each color separately, the black print coming last, as in the regular color-printing process.”

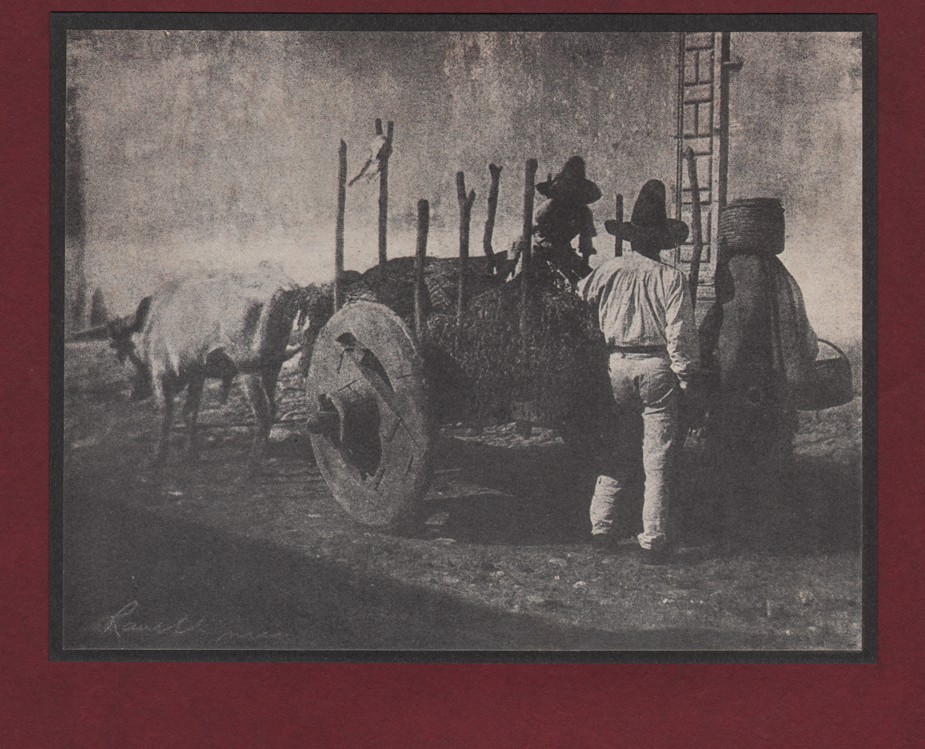

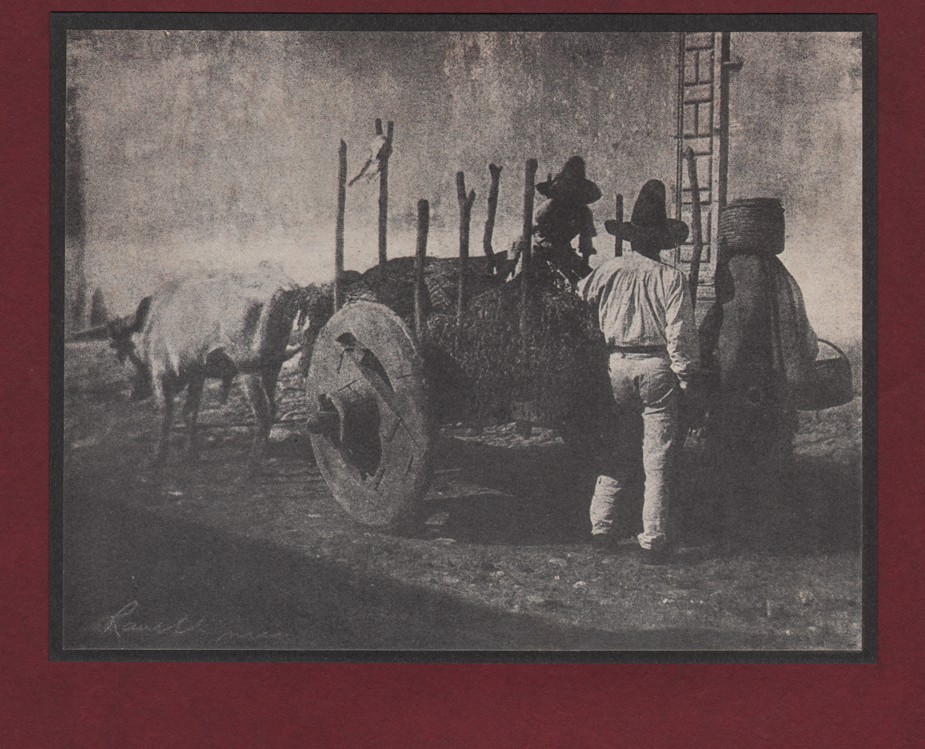

“An Ox Cart” (Mexico): Henry Ravell, American: 1864-1930. 1905: Vintage halftone tipped to mount: 16.6 x 21.4 | 17.4 x 22.2 | 45.0 x 30.5 cm “This mount is Sultan Bokhara and Royal Melton Egyptine Made by the Niagara Paper Mills”. Taken in Mexico ca. 1900-05, this is one of the earliest published examples of a Ravell photograph to appear in the popular press. It was included in the luxury portfolio publication “Art in Photography” issued by the Photo Era Publishing Company of Boston. From: PhotoSeed Archive

Ravell continued to work in Mexico until about 1914, when it is believed he moved back to the Los Angeles area of California in order to escape the Civil War (Mexican Revolution) then engulfing the country. A short biography included in the 1978 volume Pictorial Photography in Britain 1900-1920 gives 1916 as a slightly later date, although it was likely he was traveling back and forth from Mexico to the U.S. several times during this tumultuous time:

“In 1916 an article entitled “Cathedrals of Mexico”, illustrated by his work, was published in Harper’s magazine. About this time he left Mexico, almost as a refugee. His studio in Cuernavaca was destroyed by rebels. He moved to California where he began to photograph near Carmel and settled at Santa Barbara.”

Now that this American born “refugee” was back in his home country for good, he immediately set out photographing the beauty of the southern California coastline, with an emphasis on capturing the numerous entanglements of old cypress trees set against the landscape and Pacific Ocean. Conveniently, and perhaps not coincidentally, Lockwood de Forest had moved permanently to Santa Barbara in 1915 after wintering in the area since 1902, with his professional connections to the world of art giving Henry and his work credibility and entrance to a larger audience. These included retrospective exhibitions of nearly 100 framed works of his Mexican and California subjects at major American institutions. These began in October, 1918 at the Pratt Institute Art Gallery in Brooklyn and continued into 1919 at the Albright Art Gallery in Buffalo, New York followed by shows the same year at the newly opened Cleveland Museum of Art and then at the Chicago Art Institute.

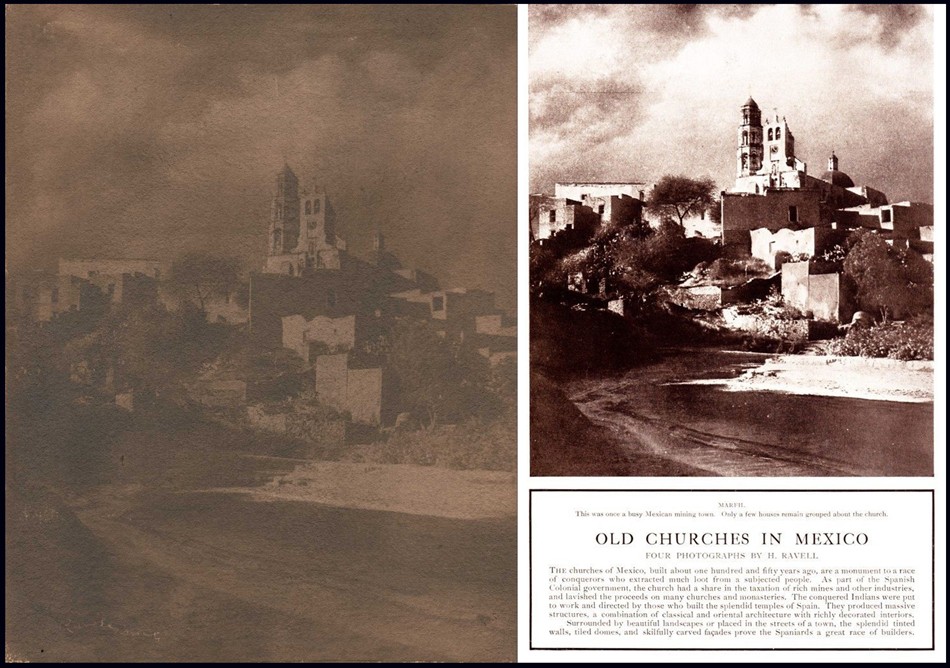

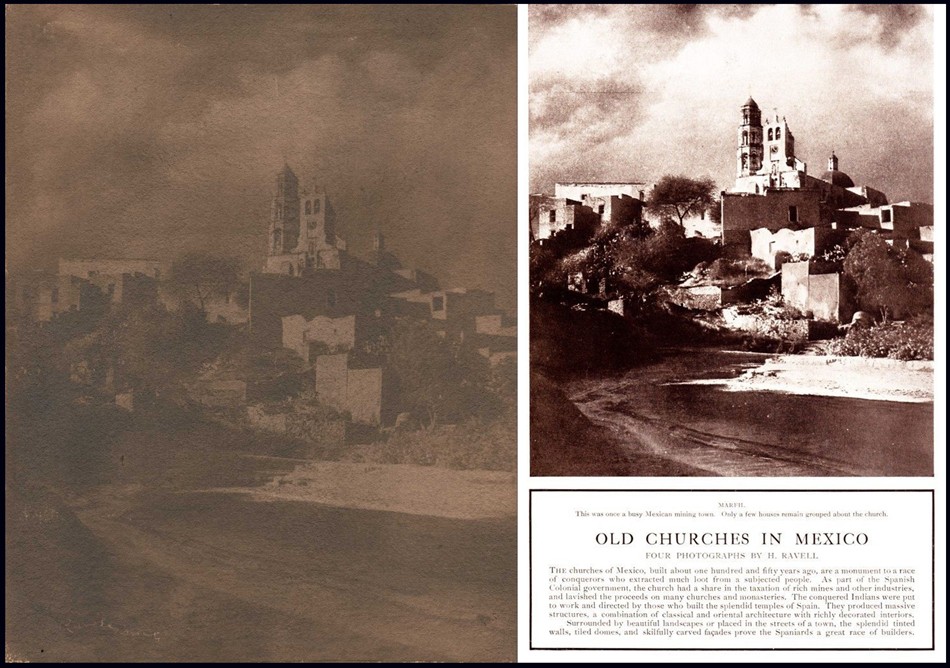

Left: “Marfil: Templo De Marfil De Arriba”: Henry Ravell, American: 1864-1930. Vintage gum print c. 1900-10: 37.4 x 29.0 cm. Still standing today, this church constructed in the Baroque style is located in Marfil, a suburb of the central Mexican city of Guanajuato. The church is colloquially known as “La Iglesia de Arriba”, or the “Church up Top”. From: PhotoSeed Archive Right: Four photographs of Mexican churches by Henry Ravell, including the Templo De Marfil De Arriba photograph, were published in the February, 1914 issue of Century Magazine for a picture spread titled “Old Churches in Mexico”: “The churches of Mexico, built about one hundred and fifty years ago, are a monument to a race of conquerors who extracted much loot from a subjected people. As part of the Spanish Colonial government, the church had a share in the taxation of rich mines and other industries, and lavished the proceeds on many churches and monasteries. The conquered Indians were put to work and directed by those who built the splendid temples of Spain. They produced massive structures, a combination of classical and oriental architecture with richly decorated interiors. Surrounded by beautiful landscapes or placed in the streets of a town, the splendid tinted walls, tiled domes, and skilfully carved facades prove the Spaniards a great race of builders.” From: Internet Archive

Henry Ravell would continue to exhibit his work late into the 1920’s at smaller venues, one example being a tri-colored gum print titled “Mexican Peon Boy” shown at the 1927 Los Angeles Salon and remarked on by Camera Craft, his gum prints deemed “for which he has gained a warranted renown”. Gum printing was indeed so important to the artist that he listed “Gum Printer” as his occupation for the 1920 U.S. Census.

Left: “Pine and Cypress, Pebble Beach”: Henry Ravell, American: 1864-1930. Vintage gum print ca. 1915-20. (Museum of Wayne County History accession #Pi 176a with verso sticker additionally listing number 17 and $3.00) Middle: “Big Splash” (California coastline) Henry Ravell, American: 1864-1930. Vintage gum print ca. 1915-20. (Museum of Wayne County History accession #Pi 176m with verso sticker additionally listing number 122 and $12.00) Right: “Untitled Marine Landscape” (Mexico or California): Henry Ravell, American: 1864-1930. Vintage multiple colored gum print ca. 1907-1920. (Museum of Wayne County History accession #Pi 176n with verso sticker additionally listing number 156 ) All: Courtesy Museum of Wayne County History, Lyons N.Y.

The Albright Art Gallery was an important venue for Ravell’s work, considering the groundbreaking exhibition it previously hosted in November, 1910: the International Exhibition of Pictorial Photography. Organized by the Photo-Secession under the direction of Alfred Stieglitz, it was “the first exhibition held at an American museum that aimed to elevate photography’s stature from a purely scientific pursuit to a visual form of artistic expression.” Even nine years later, in 1919, at a time when museum shows devoted to the work of a singular photographer anywhere in the world were still few and far between and remained so decades later, it’s refreshing in the present to read observations by one curator remarking on Ravell’s 93 framed photographs displayed at the Albright gallery for Academy Notes, the mouthpiece for The Buffalo Fine Arts Academy:

“THE collection of photographs by H. Ravell—which was on view in the gallery during the last week in February and all of March—is very unique and valuable. These photographs are technically known as gum-prints and have all the painter’s quality in their execution. They do not impress one as photographs but rather as work directly from the artist’s brush. The photographs were made by H. Ravell who is now in Santa Barbara. Many of the pictures were taken near Carmel, California, a seashore of much variety where the fantastic cypress trees with their twisted dramatic forms produce wonderful compositions against sea and sky.” …This is but a short description of the remarkable exhibition of photographs shown at the Albright Art Gallery. It was seen by many art lovers and appreciated especially by all of those interested in artistic photography.” (4.)

“Ox Cart- Sunset”: Henry Ravell, American: 1864-1930. Vintage gum print ca. 1900-10. Image: 27.0 x 32.6 cm presented loose within dark brown paper folder with overall support dimensions of 58.8 x 36.7 cm. Wearing a traditional sombrero hat, (Sombrero de charro) the driver of this ox or bullock cart pauses atop a full load of what looks like hay or silage. This Mexican scene may date to around 1905-consistent with a different view by the artist of an ox cart published that year in “Art in Photography” by the the Photo Era Publishing Company of Boston. From: PhotoSeed Archive

A reevaluation of Henry Ravell’s body of work is important to consider in the present given the broad acknowledgement of his talent by major institutions and the popular press for the benefit of many large audiences over 100 years ago. An important pictorialist photographer who was also a painter, Henry Ravell was a striver and apprentice graduate inspired by his father’s steady trade in the New York state village of Lyons who embraced a love for craft and mastery of art. Together, these skills gave him the passion to embrace adventure in capturing the beauty in far-off Mexico and southern California for the ages.

Four original gum prints in the PhotoSeed Archive can be seen here, each listing an expanded biography, timeline and major institutional holdings for the artist.

Afterword | Notes

A conundrum on internet research into Henry Ravell’s artistic output reveals itself quickly. The bottom line is that most every painting on the web attributed to Henry Ravell the photographer is not by him. Instead, through PhotoSeed’s research and purchase of the small painting: “The Ripers”, (The Reapers) the true identity of this artist can now be revealed as Henry Etienne Ravel. (1872-1962) Born in Naples Italy to French citizens, Henry Ravel immigrated to America in 1906 and became a naturalized US citizen in 1920. A transportation clerk by trade in the early 1920’s, his paintings- many done in Europe- date from ca. 1930’s-1950’s. What causes the confusion is that like Henry Ravell the photographer, who signed his photographs “H. Ravell”, Henry Ravel the painter also signed his work similarly, but as “H. Ravel” Numerous examples of his paintings show up on Google searches-unlike the real and quite rare examples of watercolors done by Ravell the photographer. I’ve included links to some of these paintings on the page showing “The Ripers”. As always- buyer beware and do your homework!

1. C. Ravel won a $3.00 premium for “Best Daguerreotypes” during the Annual Fair of the Madison County Agricultural Society held at Morrisville, (N.Y.) on the 15th, 16th and 17th days of September,1857 according to a newspaper account in the Cazenovia Republican. Shout out to the Pioneer American Photographers 1839-1860 website. Langdon’s List of 19th & Early 20th Century Photographers additionally list Ravel working in Manlius, New York in the 1859 N.Y. State Business Directory.

2. See: The Lyons Republican & Clyde Times: Lyons, N.Y. Thursday, March 21, 1940. Article excerpts: HENRY RAVELL: “Resided in Lyons for twenty-eight years, died in Los Angeles California, January 20, 1930. This account was written by his sister, Mrs. Florence Ravell Lothrop, of 721 Fifth Street North, St. Petersburg, Florida.: “Henry had no special training in any school or under any masters except my father, Charles Herring Ravel, who was born in Boston, England, and became one of the first photographers in the United States. His forbears came over with William the Conqueror to England, which accounts for the one “L” in the name. My mother was annoyed because most people called her Mrs. Rav’-el and persuaded my father to add “L”, so the family adopted that spelling of our name.…Henry studied and experimented all his life. His photographic subjects were portraits, landscapes, street scenes, trees, cloud and moonlight effects. His Mexican Cathedrals were especially noteworthy. He used both oils and water colors, but his favorite work was photography, and the gum print process. This process was original with an Austrian who refused to make it known, but Henry experimented until he developed it, and later gave the formula to the world. I remember seeing around his studio, pans of water about three inches deep. The photo-print was put into the water and pigments of paint dropped on it, this gave the effect when completed of a soft beautiful painting. My description to an artist will seem crude but that is as I recall it.…Henry never taught, that is, acted as a teacher in any school, and I do not know what societies he belonged. He exhibited in the Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, Salon about 1907. From the thousands of photographs submitted, three of his were among the 237 accepted. His work was exhibited at the Salmagundi Club, New York City; Thurber’s and Anderson’s Galleries in Chicago, Los Angeles, California, and many, many other places. Fifteen of his photographs are at the Metropolitan Museum, New York City. Seven are Mexican subjects and eight are California trees. These were selected by Forest Lockwood.(sic) After Henry’s death at Los Angeles, California, in 1930, a request came for him to send an exhibit to the Fifth International Photographic Salon of Japan held at Tokyo and Osaka in May, 1931.”

3. In the December, 1908 issue of Boston’s Photo-Era, a short article titled “Gum-Prints In Colors” appeared, linking Ravell’s gum prints as being similar to “a collection of prints by the same process, probably with modifications” to work done by the Hofmeister brothers and Müller. These German works were shown at the offices of The British Journal of Photography in London’s Strand from September 28- October 24, 1907.

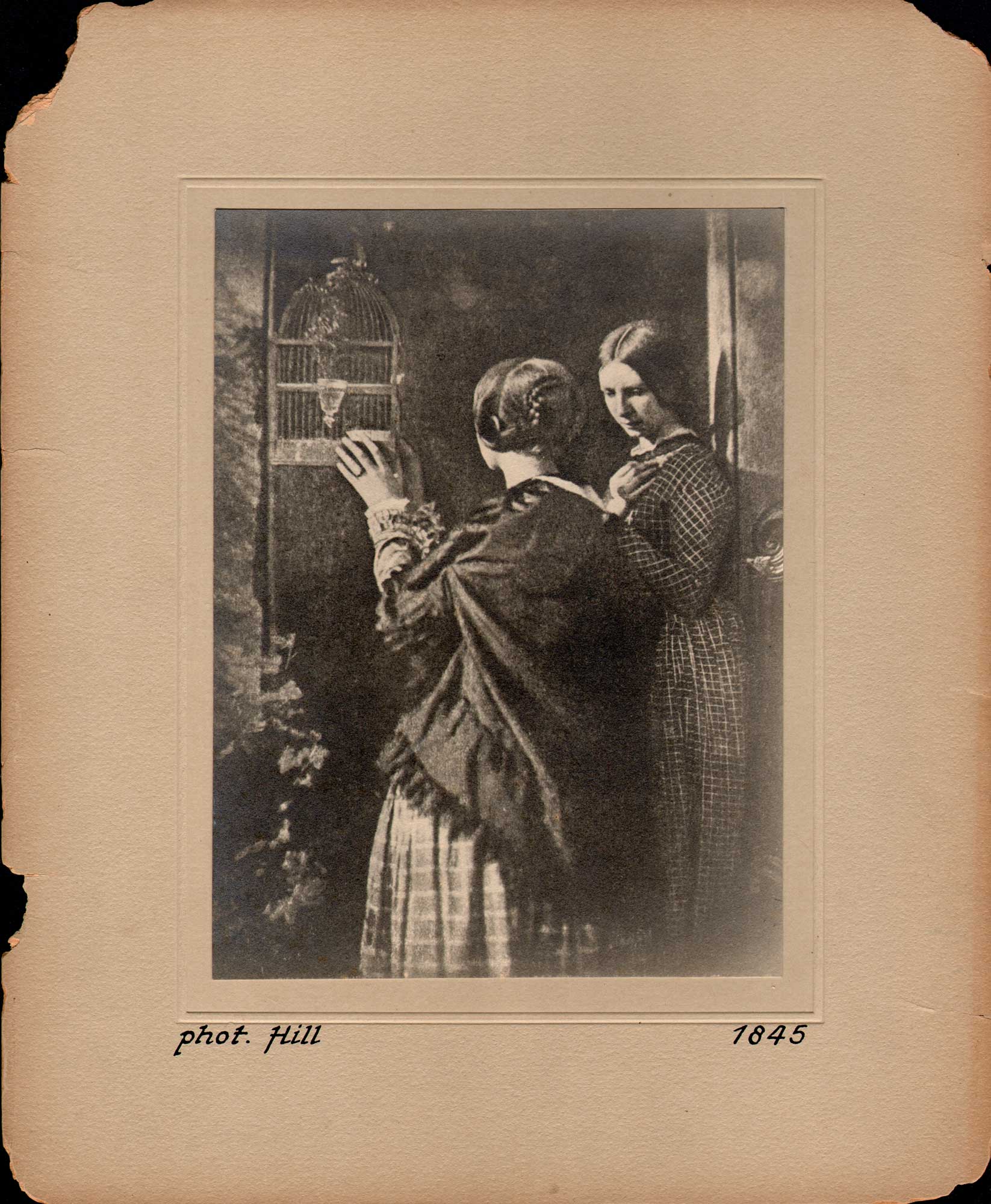

4. See: Academy Notes: The Buffalo Fine Arts Academy: Albright Art Gallery: Buffalo, New York: vol. XIV: Jan.-Oct. 1919, p. 67