Year

2014

12 entries in this year | view all years

Silent Night

Posted December 2014 in Exhibitions, New Additions, Significant Photographs

Detail: "Thru the Back Window": Charles A. Hellmuth: American: vintage 1924 Wellington bromoil print: 32.1 x 24.0 cm | 50.7 x 40.6 cm: from: PhotoSeed Archive

Detail: "Thru the Back Window": Charles A. Hellmuth: American: vintage 1924 Wellington bromoil print: 32.1 x 24.0 cm | 50.7 x 40.6 cm: from: PhotoSeed Archive

Genre meets Genius

Posted November 2014 in Engraving, New Additions, Painters|Photographers, Significant Photographers, Typography

Although long forgotten, amateur photographer John E. Dumont (1856-1944) figures prominently in the early years of American pictorial photography. However, a professional and better known acquaintance of his may change our understanding after my discovery of a small label on the back of a Dumont print made its’ way into the archive.

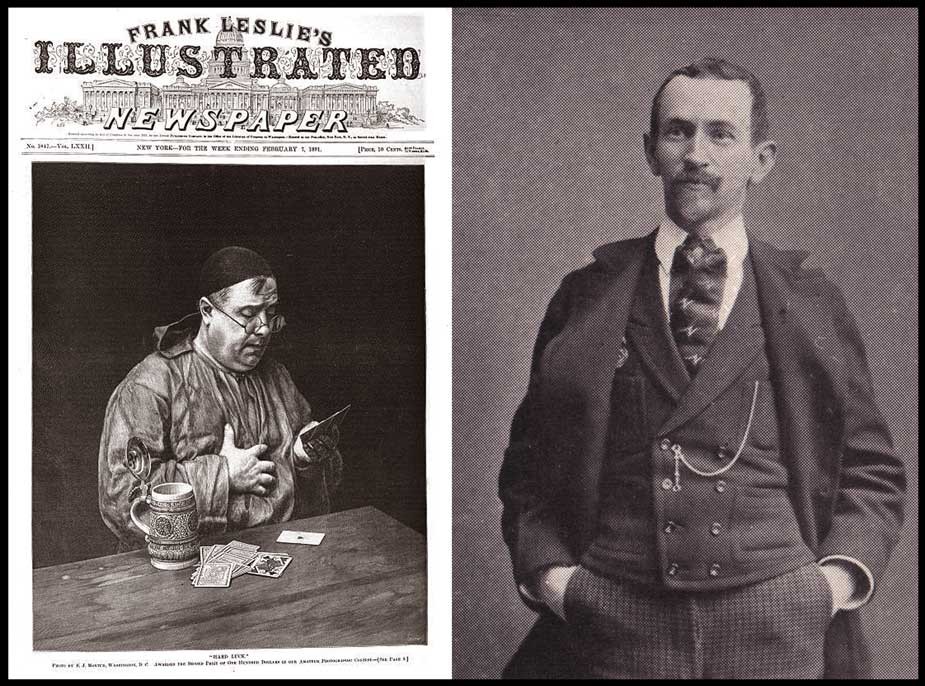

Left: "Hard Luck", showing a monk playing a losing hand of cards, was most likely taken by John E. Dumont in 1890. Shown here as the cover illustration of Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper for Feb. 7, 1891, it is reproduced as a wood engraving from the original photograph, and earned Dumont a second place award and $100.00 in Leslie's Amateur Photographic Contest which closed in January, 1891. Dumont went on to copyright "Hard Luck" in 1892. (original from Pennsylvania State University) Right: Halftone portrait of photographer John E. Dumont of Rochester, New York by unknown photographer. 6.3 x 4.7 cm. Reproduced as part of a series of portraits of "Prominent Amateur Photographers" in the Nov., 1893 issue of the American Amateur Photographer journal. (p. 513) : from: PhotoSeed Archive

Left: "Hard Luck", showing a monk playing a losing hand of cards, was most likely taken by John E. Dumont in 1890. Shown here as the cover illustration of Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper for Feb. 7, 1891, it is reproduced as a wood engraving from the original photograph, and earned Dumont a second place award and $100.00 in Leslie's Amateur Photographic Contest which closed in January, 1891. Dumont went on to copyright "Hard Luck" in 1892. (original from Pennsylvania State University) Right: Halftone portrait of photographer John E. Dumont of Rochester, New York by unknown photographer. 6.3 x 4.7 cm. Reproduced as part of a series of portraits of "Prominent Amateur Photographers" in the Nov., 1893 issue of the American Amateur Photographer journal. (p. 513) : from: PhotoSeed Archive

Established in business beginning in 1881 in Rochester, New York as a wholesale merchandise and grocery broker specializing in items like sugars, teas, and coffees, Dumont took up photography in 1884 and was soon entering and winning awards in photographic salons around the world.

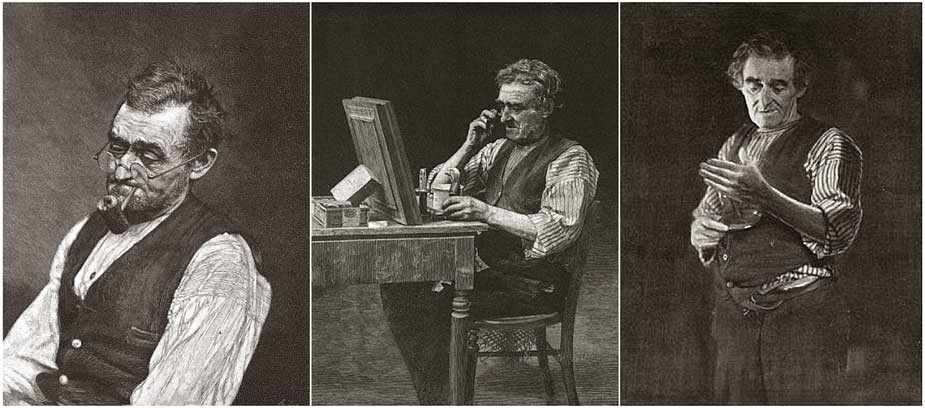

Taken in 1887, photographer John E. Dumont of Rochester, New York made this series of genre portrait photographs of a gentleman he described as "an old man who used to peddle oranges around the streets and offices in this city". Left: "A Quite Pipe": woodcut engraved from a copyright photograph from Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper Amateur Photographic Contest: published Jan., 17, 1891. Middle: "The Old Shaver": woodcut engraved from a copyright photograph from Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper Amateur Photographic Contest: published Jan., 24, 1891. Right: "The Toiler's Good-Night" : woodcut engraved from a copyright photograph illustrating a poem from Leslie's Illustrated Weekly: published Dec., 14, 1893: originals from Pennsylvania State University

Taken in 1887, photographer John E. Dumont of Rochester, New York made this series of genre portrait photographs of a gentleman he described as "an old man who used to peddle oranges around the streets and offices in this city". Left: "A Quite Pipe": woodcut engraved from a copyright photograph from Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper Amateur Photographic Contest: published Jan., 17, 1891. Middle: "The Old Shaver": woodcut engraved from a copyright photograph from Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper Amateur Photographic Contest: published Jan., 24, 1891. Right: "The Toiler's Good-Night" : woodcut engraved from a copyright photograph illustrating a poem from Leslie's Illustrated Weekly: published Dec., 14, 1893: originals from Pennsylvania State University

Specializing in genre scenes, his photographs were published frequently, reaching a high point when his well known study of a monk playing a losing hand of cards titled Hard Luck was published as the cover illustration (converted to a wood engraving) for Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper in early 1891, the same year he won a grand diploma at the groundbreaking Vienna Salon of Photographic Art, the highest accolade awarded for the very few American entrants whose work was even accepted, including the now venerable Alfred Stieglitz, who had only come back to America from Europe the year before.

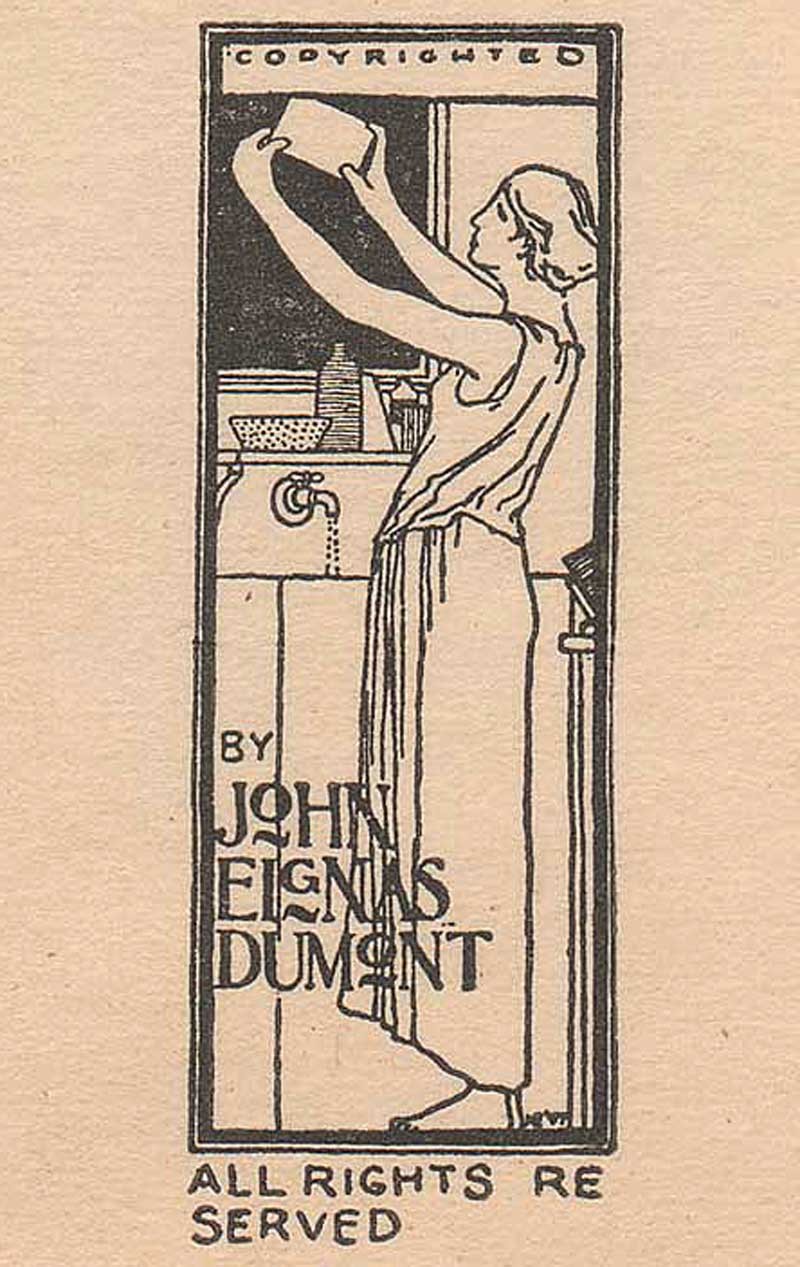

Artist: Harvey Ellis, American: 1897: medium: wood engraving: subject: copyright label for amateur American photographer John Eignas Dumont. Plate intended to represent "the genius of photography surrounded by the accessories of the "dark room." Design: 3.4 x 1.3 cm | Label: 7.0 x 4.5 cm. Label is a variant of an ex libris bookplate Ellis designed for Dumont. from: PhotoSeed Archive

Artist: Harvey Ellis, American: 1897: medium: wood engraving: subject: copyright label for amateur American photographer John Eignas Dumont. Plate intended to represent "the genius of photography surrounded by the accessories of the "dark room." Design: 3.4 x 1.3 cm | Label: 7.0 x 4.5 cm. Label is a variant of an ex libris bookplate Ellis designed for Dumont. from: PhotoSeed Archive

It was therefore a delightful discovery which took place for me recently after a signed Dumont carbon print of The Dice Players exhibited in the Royal Photographic Societies’ annual salon the same year as the Vienna exhibition was acquired for the archive. But what makes it special for the confluence of art photography and evidence a new incarnation of the English Arts & Crafts movement had taken hold after arriving on American shores was a later 1897 copyright label affixed to the rear of the mounted print. A design featuring an Art-Nouveau style woodcut engraving of a woman in a darkroom holding up a glass plate, I soon discovered it was the work of noted American artist, architect and designer Harvey Ellis. (1852-1904)

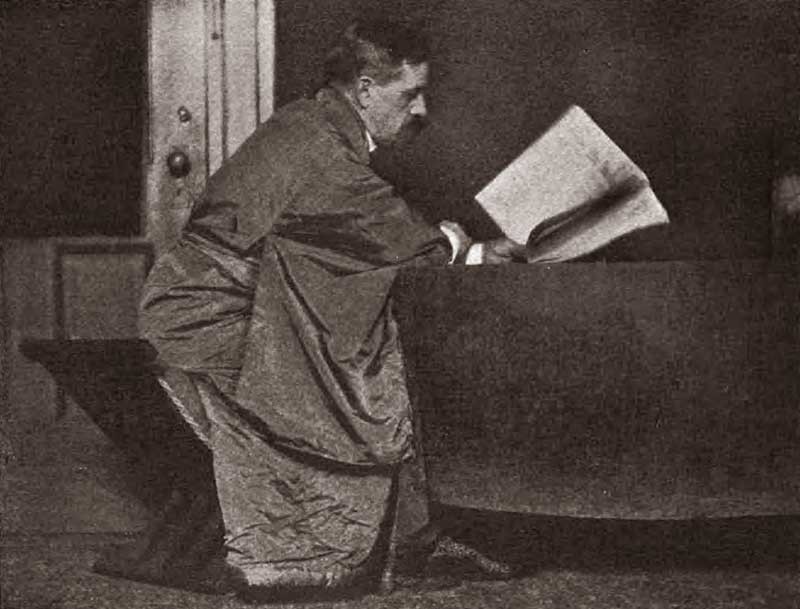

Photographic portrait of American artist, architect and designer Harvey Ellis. (1852-1904) unknown photographer: reproduced as halftone and published in the Dec., 1908 issue of The Architectural Review illustrating article on Ellis by Claude Bragdon titled Harvey Ellis: A Portrait Sketch: p. 173. Original from The University of Michigan

Photographic portrait of American artist, architect and designer Harvey Ellis. (1852-1904) unknown photographer: reproduced as halftone and published in the Dec., 1908 issue of The Architectural Review illustrating article on Ellis by Claude Bragdon titled Harvey Ellis: A Portrait Sketch: p. 173. Original from The University of Michigan

Never heard of him? Today, Ellis seems only to be remembered for the brief work he did in the last months of his life in 1903 for among other things, designing mission-style furniture and interior renderings of Craftsman homes in the Syracuse, New York-based architecture department for his American employer, Gustav Stickley, (1858-1942) the leader of the nascent American Arts and Crafts movement. But this is far from a full portrait of Ellis. A contemporary- architect, author, and theater designer Claude Bragdon- (1866-1946) gave a fuller account of Harvey Ellis in a posthumous outline for the December, 1908 issue of The Architectural Review. A few excerpts:

HARVEY ELLIS was a genius. This is a statement which may excite only incredulity in the minds of the many who never heard his name or knew him only by his published drawings, but it will have the instant concurrence of the few who knew well the man himself. There is the genius which achieves, and the genius which inspires others to achievement. Had it not been for the evil fairy (alcohol-editor) which presided at his birth and ruled his destiny, Harvey Ellis might have been numbered among the former; that is, he might have been a prominent, instead of an obscure, figure in that aesthetic awakening of America, now going on, of which he was among the pioneers; but even so he exercised an influence more potent than some whose names are better remembered. (p. 173)

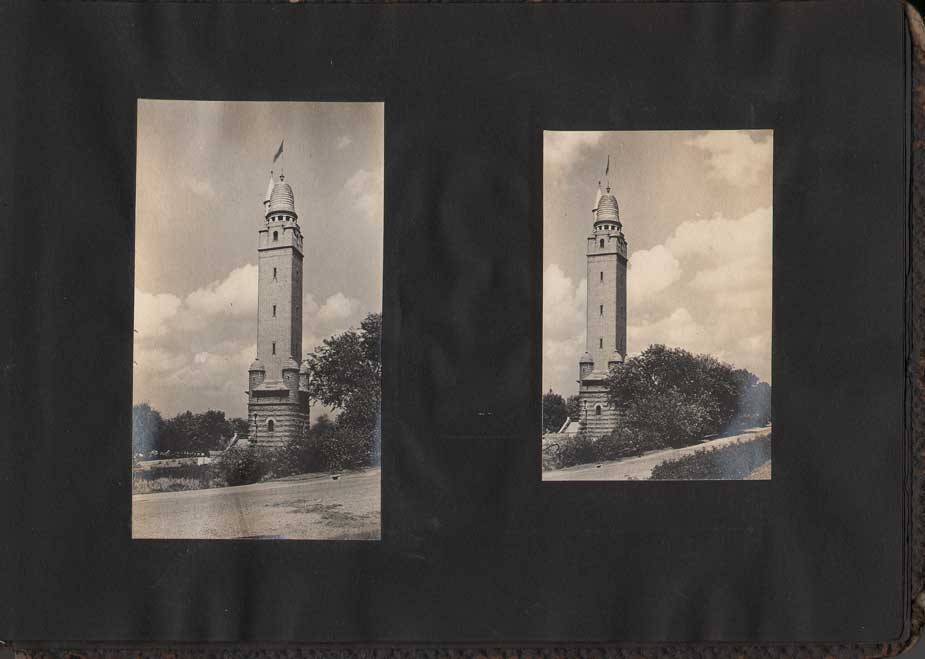

Although many designs by Harvey Ellis were never realized in the physical form, there are notable exceptions. The Compton Hill Water Tower in Reservoir Park, St. Louis, MO, is one landmark still standing. Topping out at 179 feet, (55 m) the structure was designed by Ellis in 1896 or 97 while employed by the St. Louis architectural firm of George R. Mann and Edmond J. Eckel, and built in 1898 in the French Romanesque style of rusticated limestone and buff brick and finished in terra cotta. The tower was decommissioned in 1929 and placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1972. Photographer: Leo Kraft, American: ca. 1915: gelatin silver prints pasted in album: left: 12.1 x 6.9 cm | right: 9.8 x 6.3 cm : support: 17.6 x 25.2 cm. from: PhotoSeed Archive

Although many designs by Harvey Ellis were never realized in the physical form, there are notable exceptions. The Compton Hill Water Tower in Reservoir Park, St. Louis, MO, is one landmark still standing. Topping out at 179 feet, (55 m) the structure was designed by Ellis in 1896 or 97 while employed by the St. Louis architectural firm of George R. Mann and Edmond J. Eckel, and built in 1898 in the French Romanesque style of rusticated limestone and buff brick and finished in terra cotta. The tower was decommissioned in 1929 and placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1972. Photographer: Leo Kraft, American: ca. 1915: gelatin silver prints pasted in album: left: 12.1 x 6.9 cm | right: 9.8 x 6.3 cm : support: 17.6 x 25.2 cm. from: PhotoSeed Archive

… “There’s one type of mind,” Harvey remarked, “which would discover a symbol of the Trinity in three angles of a rail fence; and another which would criticize the detail of the Great White Throne itself.” Symmetry (the love of which is a sure index of the Classic mind) was his particular abhorrence. “Not symmetry, but balance,” he used to say. (p. 175)

Transient, and an unconventional architect and designer for his day, Ellis moved about the country working for firms in Minneapolis and St. Louis before returning to his native Rochester in 1893. It was sometime after this period that he most likely encountered and made the friendship of Dumont. In 1897, both became founding members of the Rochester Arts and Crafts Society, with Ellis serving as first president. That year, Dumont commissioned Ellis to design an ex libris book plate for him which was reworked slightly and reduced in size for use as a photographic copyright label-an example of which I found affixed to the verso of The Dice Players.

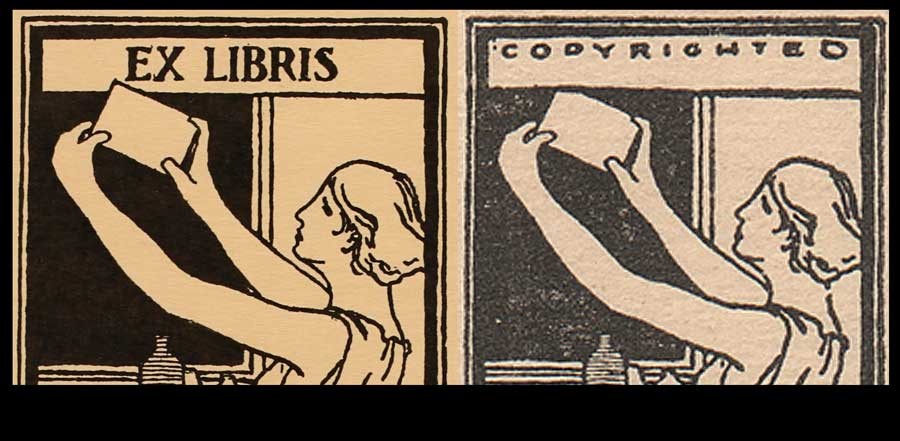

Details: Harvey Ellis: 1897: wood engraving: Ex Libris bookplate and Copyright label for American amateur photographer John Eignas Dumont : Left: bookplate: 9.4 x 4.1 cm: Jensen Tusch Collection- Frederikshavn Kunstmuseum & Exlibrissamling- Denmark: Right: copyright label: 3.4 x 1.3 cm | 7.0 x 4.5 cm : from: PhotoSeed Archive

Details: Harvey Ellis: 1897: wood engraving: Ex Libris bookplate and Copyright label for American amateur photographer John Eignas Dumont : Left: bookplate: 9.4 x 4.1 cm: Jensen Tusch Collection- Frederikshavn Kunstmuseum & Exlibrissamling- Denmark: Right: copyright label: 3.4 x 1.3 cm | 7.0 x 4.5 cm : from: PhotoSeed Archive

In 1899, the original bookplate was described in the pages of the London Journal of the Ex Libris Society:

DUMONT BOOK-PLATES.

By the kindness of a member we are enabled to give an illustration of the book-plate of Mr. John E. Dumont, of Rochester, N.Y., designed by Mr. Harvey Ellis, of the same city. Mr. Dumont is a leading photographer in America, and his works are well known in England. The plate represents the genius of photography surrounded by the accessories of the “dark room.” Mr. Ellis, the designer, is a prominent architect and a water-colour artist of repute. The plate, here given, is graceful in design and execution. (p. 128)

The friendship between Dumont and Ellis extended to 1903. Now serving as president of the Rochester Camera Club, (founded 1889) Dumont was joined by Ellis and future American Photo-Secession member and club member Albert Boursalt while acting as judges for the club’s inaugural photographic exhibition in the newly erected Eastman Building on the campus of the Mechanics Institute. (which became RIT) From March 30 to April 11, over 200 framed photographs were displayed in a building made possible by Rochester philanthropist and Kodak head George Eastman. An account of the exhibition was published, along with the role of Ellis as judge, in the May, 1903 issue of the American Amateur Photographer. An excerpt:

It is stated by Mr. Dumont, who is most familiar with all of the photographic exhibits ever held here, that this of the Rochester Camera Club is by far the best, largest and most meritorious of any ever held in Rochester. Harvey Ellis, whose ability as an art critic is recognized by all, says that there are just as good pictures shown by the local exhibitions as any from out of the city, and that more than one half of the pictures hung are as good as those shown in any of the salons in the country, not excepting New York and Philadelphia, which rank among the highest in merit. (pp. 223-24)

Detail: "The Dice Players": 1891: print ca. 1897 or later: John E. Dumont: carbon print: 29.2 x 25.1 cm (flush mounted to board) : This classic genre photograph by Dumont showing a group of men playing dice (possibly the con game "chuck-a-luck") was first shown in the annual exhibition of the Royal Photographic Society in 1891 and further earned him a gold medal in another contest the same year sponsored by the English journal the Amateur Photographer. From: PhotoSeed Archive

Detail: "The Dice Players": 1891: print ca. 1897 or later: John E. Dumont: carbon print: 29.2 x 25.1 cm (flush mounted to board) : This classic genre photograph by Dumont showing a group of men playing dice (possibly the con game "chuck-a-luck") was first shown in the annual exhibition of the Royal Photographic Society in 1891 and further earned him a gold medal in another contest the same year sponsored by the English journal the Amateur Photographer. From: PhotoSeed Archive

But what immediately followed in the new Eastman Building from April 15-25, 1903: an “Exhibition of Art Craftsmanship”, featuring work from Gustav Stickley’s Craftsman Workshops, (1.) would turn out to be more significant in the overall advancement of the American Arts and Crafts movement compared to the photographic exhibition. A motivating factor perhaps? As it turned out, Harvey Ellis organized the Craftsman show, joining the Stickley firm a month later where he finished a remarkable career.

1. Historical Background: R.I.T. online resource accessed Nov., 2014: “In 1902 the Department of Decorative Arts and Crafts was established at Mechanics Institute under the leadership of Theodore Hanford Pond. An “Exhibition of Art Craftsmanship”, featuring the work of Gustav Stickley’s Craftsman Workshops, was presented in the Mechanics Institute’s Eastman Building, 15-25 April 1903.”

Witching You the Best

Posted October 2014 in New Additions, Significant Photographs

This spooky season. For more on this photograph with a short overview on the pictorial work of Maine resident Bertrand H. Wentworth, proceed here.

Detail: Bertrand H. Wentworth: American: "Witches' Wood" : (34.9 x 27.1 cm) : vintage gelatin silver print: ca. 1915-20. Perhaps showing the photographer himself dressed as a witch, locations used by Wentworth for his photographs were described in the Oct., 1919 issue of The American Magazine of Art: "The sea, the pine woods, winter landscapes, he has made his specialty, and the majority of his themes he has found in the vicinity of his home at Gardiner, Maine." from: PhotoSeed Archive

Detail: Bertrand H. Wentworth: American: "Witches' Wood" : (34.9 x 27.1 cm) : vintage gelatin silver print: ca. 1915-20. Perhaps showing the photographer himself dressed as a witch, locations used by Wentworth for his photographs were described in the Oct., 1919 issue of The American Magazine of Art: "The sea, the pine woods, winter landscapes, he has made his specialty, and the majority of his themes he has found in the vicinity of his home at Gardiner, Maine." from: PhotoSeed ArchiveBeauty, Underwater

Posted October 2014 in History of Photography, New Additions, Scientific Photography, Significant Photographs

With Autumn upon us in the more seasonal regions of the United States, a remembrance, particularly if we are young, of the joys of cooling off in the lakes, ponds, and rivers of our youth.

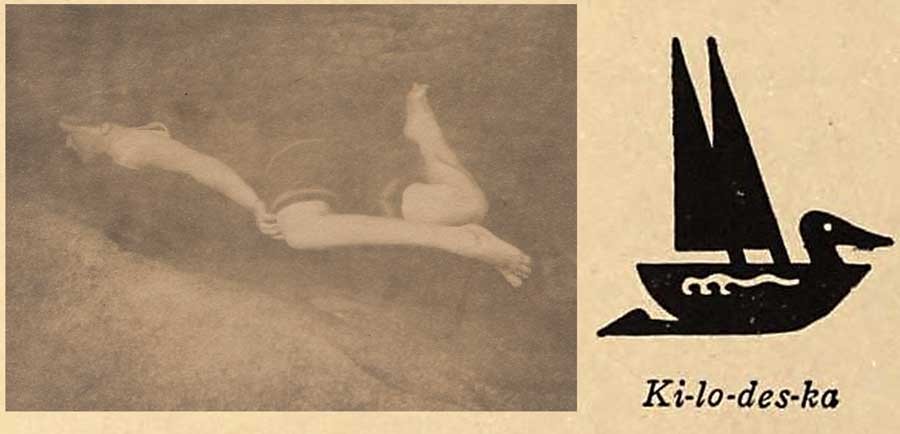

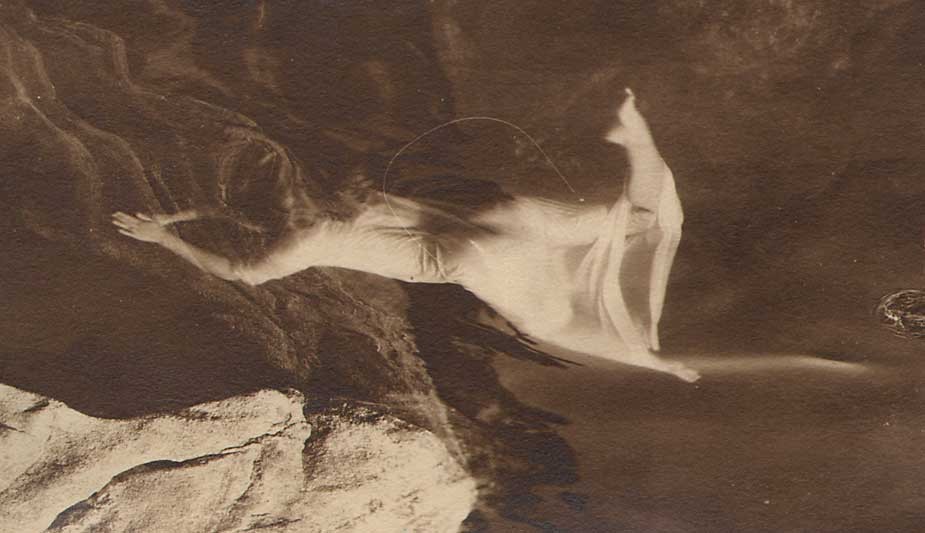

Detail: Gelatin silver print: "Mermaid Study : Ki-lo-des-ka": ca. 1914 or before: by Charlotte Vetter Gulick: image: 7.1 x 9.2 cm: mount: 16.7 x 22.7 cm. Subject shows Katharine "Kitty" Gulick swimming underwater at Camp Wohelo in Maine. from: PhotoSeed Archive

Detail: Gelatin silver print: "Mermaid Study : Ki-lo-des-ka": ca. 1914 or before: by Charlotte Vetter Gulick: image: 7.1 x 9.2 cm: mount: 16.7 x 22.7 cm. Subject shows Katharine "Kitty" Gulick swimming underwater at Camp Wohelo in Maine. from: PhotoSeed Archive

Memories made all the more indelible if we ever had the opportunity to attend summer camp.

So lets go further and think about taking a photograph of someone underwater. Not a photo taken with a camera underwater, a remarkable feat in itself accomplished beginning in 1893 by the Frenchman Louis Boutan, (1.) but from the outside looking in.

Before researching a series of photographs recently acquired for this archive showing a young woman swimming underwater, I would have thought no big deal- perhaps they were rare but could the subject matter actually be unique? After all, they were first published for a mass audience in Everybody’s Magazine in the U.S. in August of 1914, with the author exclaiming them to be “remarkable photographs…taken under conditions not easily duplicated, and have aroused great interest among artists and others who have seen the originals.” (2.)

No doubt other examples of this activity exist in the form of vintage photographs. Snapshots perhaps-but ones where actual intent existed in order to show the beauty of the human figure swimming underwater? Before or perhaps a decade or two after 1914? Somehow I doubt it. ✻

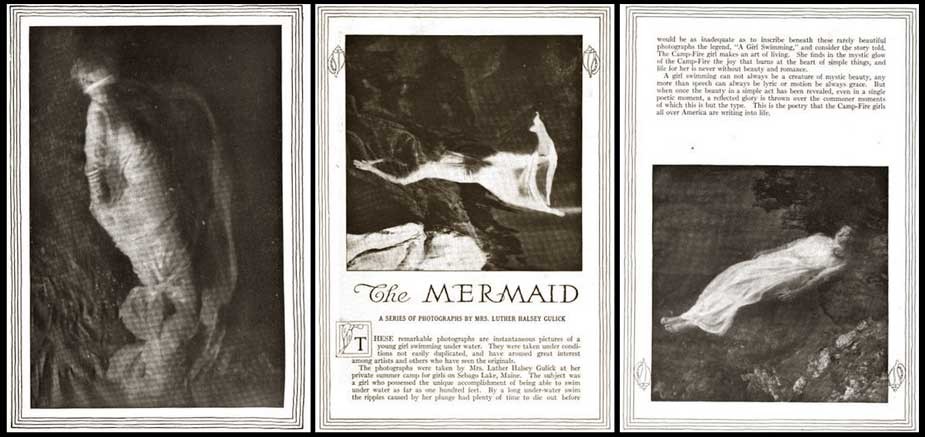

Three individual halftone and letterpress page spreads showing mermaid "Ki-lo-des-ka" (Katharine "Kitty" Gulick) swimming and lying submerged underwater: from: Everybody’s Magazine: New York: August, 1914: pp. 225-232

Three individual halftone and letterpress page spreads showing mermaid "Ki-lo-des-ka" (Katharine "Kitty" Gulick) swimming and lying submerged underwater: from: Everybody’s Magazine: New York: August, 1914: pp. 225-232

With a bit of research, I not only discovered the subject of the “mermaid” doing the swimming in the photos: Katharine “Kitty” Gulick, (1895-1968) but the remarkable story behind the amateur photographer who took them: her mother Charlotte Vetter Gulick. (1865-1928) Taken at Wohelo girls summer camp on the shore of Sebago Lake in Raymond, Maine, a camp founded in 1907 by Gulick and husband Luther Halsey Gulick (1865-1918) that is still going strong today, the following article from Everybody’s explains how these remarkable photos were taken and provides guiding principals behind the Camp Fire Girl movement founded by the photographer herself.

inset: detail: Gelatin silver print: "Mermaid Study : Ki-lo-des-ka" ca. 1914 or before: by Charlotte Vetter Gulick: image: 8.1 x 10.5 cm: mount: 16.8 x 23.2 cm: This was an early effort showing "Kitty" wearing a dark-colored bathing-suit "which was too nearly the tone of the rocks to give definition" before the garment was substituted for "a flowing garment of cheese-cloth" which showed up much better against the darkness of the water.: from: PhotoSeed Archive. Background: Camp Wohelo Indian symbol for "Ki-lo-des-ka" aka: "Water-bird": from 1915 volume by Ethel Rogers: "Sebago-Wohelo Camp Fire Girls"

inset: detail: Gelatin silver print: "Mermaid Study : Ki-lo-des-ka" ca. 1914 or before: by Charlotte Vetter Gulick: image: 8.1 x 10.5 cm: mount: 16.8 x 23.2 cm: This was an early effort showing "Kitty" wearing a dark-colored bathing-suit "which was too nearly the tone of the rocks to give definition" before the garment was substituted for "a flowing garment of cheese-cloth" which showed up much better against the darkness of the water.: from: PhotoSeed Archive. Background: Camp Wohelo Indian symbol for "Ki-lo-des-ka" aka: "Water-bird": from 1915 volume by Ethel Rogers: "Sebago-Wohelo Camp Fire Girls"

Illustrating the article were eight photographs of Wohelo camper “Ki-lo-des-ka”, or “Water-bird”, the aforementioned “Kitty” Gulick, with several of the originals formerly owned by her appearing with this post:

The Mermaid

A SERIES OF PHOTOGRAPHS BY MRS. LUTHER HALSEY GULICK

THESE remarkable photographs are instantaneous pictures of a young girl swimming under water. They were taken under conditions not easily duplicated, and have aroused great interest among artists and others who have seen the originals. The photographs were taken by Mrs. Luther Halsey Gulick at her private summer camp for girls on Sebago Lake, Maine. The subject was a girl who possessed the unique accomplishment of being able to swim under water as far as one hundred feet. By a long under-water swim the ripples caused by her plunge had plenty of time to die out before she passed the rock on which Mrs. Gulick stood with the camera.

The experiments were made on a brilliantly clear day. The water also was extraordinarily clear and the swimmer passed the camera’s field two or three feet below the surface. The final clue to success was found when a flowing garment of cheese-cloth was substituted for the dark-colored bathing-suit, which was too nearly the tone of the rocks to give definition. Both the figure and the draperies, under the equalizing buoyancy of the water, give a rare representation of poise, as they are entirely unaffected by the force of gravity.

How far short this description fails of conveying the art value of the photographs, their rhythm of line and beauty of form and tone, is significantly obvious; for in this margin of appeal to the imagination lies the motive that produced the pictures. They were taken at the birthplace of the Camp-Fire idea of which Mrs. Gulick is one of the chief sponsors.

Detail: Gelatin silver or Bromide print: "Mermaid Swimming" ("Ki-lo-des-ka") ca. 1914 or before: by Charlotte Vetter Gulick: image: 8.7 x 11.2 cm: mount: 16.5 x 22.9 cm: reproduced as opening photo for article "The Mermaid" A SERIES OF PHOTOGRAPHS BY MRS. LUTHER HALSEY GULICK: in Everybody’s Magazine: New York: August, 1914: p. 225: note: hair at center of frame result of negligence from contact-printing from original negative. from: PhotoSeed Archive

Detail: Gelatin silver or Bromide print: "Mermaid Swimming" ("Ki-lo-des-ka") ca. 1914 or before: by Charlotte Vetter Gulick: image: 8.7 x 11.2 cm: mount: 16.5 x 22.9 cm: reproduced as opening photo for article "The Mermaid" A SERIES OF PHOTOGRAPHS BY MRS. LUTHER HALSEY GULICK: in Everybody’s Magazine: New York: August, 1914: p. 225: note: hair at center of frame result of negligence from contact-printing from original negative. from: PhotoSeed Archive

The photographs are a suggestive interpretation of the first law of the Camp-Fire, “Seek beauty;” a revelation of the poetic side of one of the simple, wholesome, normal acts of life. This is the principle, full of possibilities yet undeveloped, upon which the Camp-Fire ceremonial and symbolism are based.

The first ideal of the Camp-Fire girl is the development of a well proportioned physique; a body under perfect control and responsive to every call of the spirit within. Her other ideals include an all-around training in the art of home-keeping in the modern sense, which involves a knowledge of community conditions as well as of the simple processes of home activity. This points to the further ideal of patriotism in the sense of loyalty to country, to church, to humanity, and of service in its broadest meaning.

But to hold forth these aims and say “These are the Camp-Fire” would be as inadequate as to inscribe beneath these rarely beautiful photographs the legend, “A Girl Swimming,” and consider the story told. The Camp-Fire girl makes an art of living. She finds in the mystic glow of the Camp-Fire the joy that burns at the heart of simple things, and life for her is never without beauty and romance.

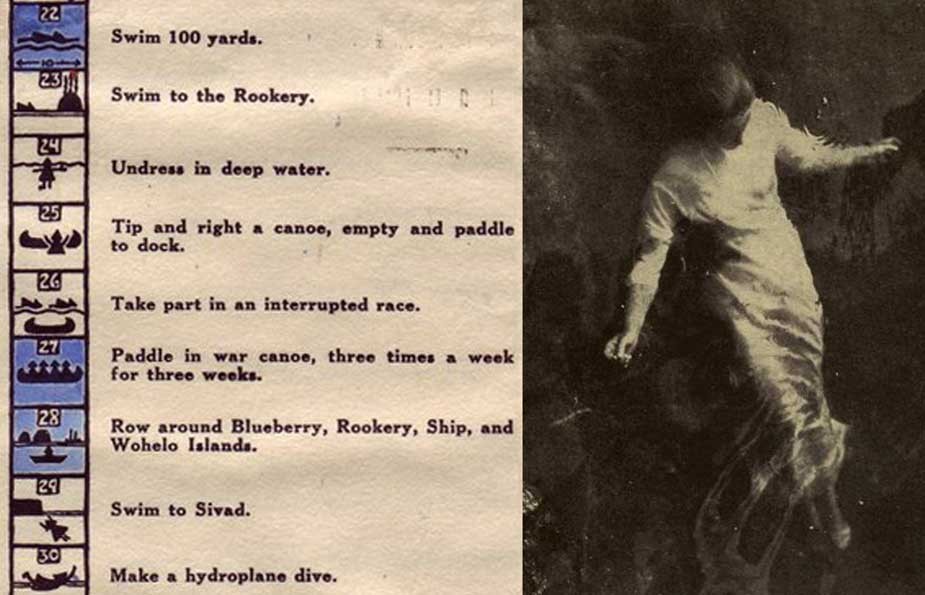

Left: example of Camp Wohelo water-related challenge symbol badges from 1920 Wohelo camp yearbook: courtesy: Gulick Family. Right: detail: full-page halftone: "Ki-lo-des-ka swimming under water" : from 1915 volume by Ethel Rogers: "Sebago-Wohelo Camp Fire Girls"

Left: example of Camp Wohelo water-related challenge symbol badges from 1920 Wohelo camp yearbook: courtesy: Gulick Family. Right: detail: full-page halftone: "Ki-lo-des-ka swimming under water" : from 1915 volume by Ethel Rogers: "Sebago-Wohelo Camp Fire Girls"

A girl swimming can not always be a creature of mystic beauty, any more than speech can always be lyric or motion be always grace. But when once the beauty in a simple act has been revealed, even in a single poetic moment, a reflected glory is thrown over the commoner moments of which this is but the type. This is the poetry that the Camp-Fire girls all over America are writing into life. (3.)

Camp Fire Girls, Basket Ball and More

Born Emma L. Vetter on Dec. 12, 1865 in Oberlin, Ohio to missionary parents, (4.) Charlotte “Lottie” Gulick was educated in Kansas public schools and undertook her secondary education at Washburn College (now Washburn University) in Topeka, Kansas doing college preparatory work. She then matriculated and earned a bachelor of arts degree from Drury College in Springfield, MO. (5.) It was at Drury that she met Luther Halsey Gulick , (1865-1918) whom she married in 1887.

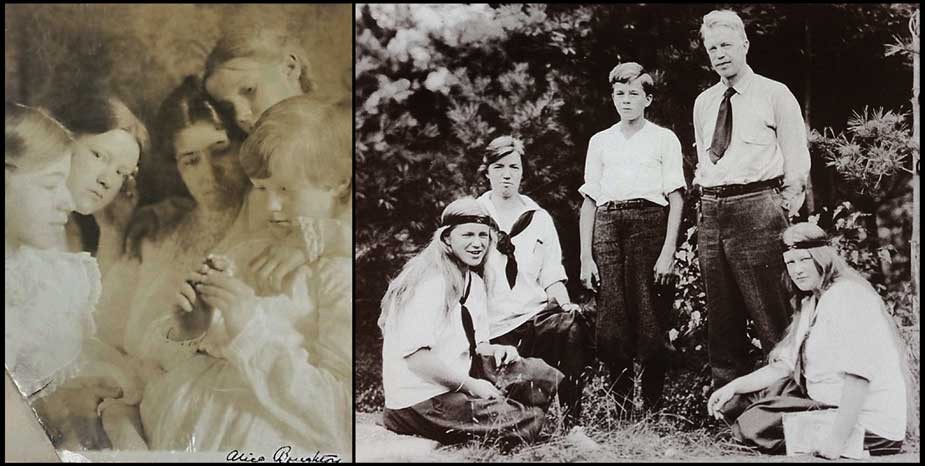

Left: photographer Charlotte Vetter Gulick is at center surrounded by her four daughters. Photograph by Alice Boughton ca. 1900. Katharine (Ki-lo-des-ka) is believed to be at right holding a flower. Reproduced later as an engraving in a New York Times article profiling the new Campfire Girls of America organization: "Girls take up the Boy Scout Idea and Band Together" (March 17, 1912) (private collection) Right: detail: members of the Gulick family from a photograph most likely taken by Charlotte Gulick around 1911. From left to right: Katharine "Kitty" Gulick (Curtis) (1895-1968); Frances "Franta" Gulick(1891-1936); Halsey Gulick; Dr. Luther Halsey Gulick (Timanous-1865-1918); Louise Gulick. (1888-1941): courtesy: Gulick Family

Left: photographer Charlotte Vetter Gulick is at center surrounded by her four daughters. Photograph by Alice Boughton ca. 1900. Katharine (Ki-lo-des-ka) is believed to be at right holding a flower. Reproduced later as an engraving in a New York Times article profiling the new Campfire Girls of America organization: "Girls take up the Boy Scout Idea and Band Together" (March 17, 1912) (private collection) Right: detail: members of the Gulick family from a photograph most likely taken by Charlotte Gulick around 1911. From left to right: Katharine "Kitty" Gulick (Curtis) (1895-1968); Frances "Franta" Gulick(1891-1936); Halsey Gulick; Dr. Luther Halsey Gulick (Timanous-1865-1918); Louise Gulick. (1888-1941): courtesy: Gulick Family

A strong advocate in the promotion of physical eduction as well as an organizer and author in his professional life, Dr. Luther Halsey Gulick also came from a missionary family, his father being missionary physician Luther Halsey Gulick Sr. (1828–1891) Receiving his medical degree from New York University in 1889, Dr. Gulick is perhaps best remembered today for his role in the development of the game of basketball, although this is but an interesting side story of a remarkable life. In 1891, while superintendent of the physical education department at the International YMCA Training School in Springfield, MA., (now Springfield College) he became the catalyst and inspiration for colleague James Naismith to first draw up rules for the new game of “Basket Ball”, with a peach basket nailed above the inside of a gymnasium playing court serving as the goal. His beliefs, as embodied in a poster issued after his death, were in the

”unity of body, mind and spirit, and in an education which includes all three. He devoted his life to establishing this ideal, by emphasizing the social and ethical values of physical exercise, especially through play and recreation.”

While at the YMCA, he was also responsible for designing the triangular logo which represented the YMCA philosophy of Mind, Body and Spirit. (6.)

Summer camp was an activity the Gulicks thrived on and made a lifestyle out of. Beginning in 1887, a year before their first child Louise was born, they established a camp on the shores of the Thames River in Gales Ferry CT. Co-educational, with the couples friends as well as extended Gulick family members acting as counselors to their own children and others, (7.) it operated for 20 years. In order to share what was learned to a larger audience of girls, the couple then established Camp Wohelo on Sebago Lake in 1907. An acronym comprised of the three virtues of work, health, and love, Wohelo was embodied from the start as outlined in 1915 by Charlotte Vetter Gulick:

I believe deeply and earnestly that spiritual health and development is a direct corollary of bodily vigor and control; that the joy that comes from the exercise of efficient muscles has its counterpart in the soul; that to exercise the one is to exercise the other.

Upon that rock has Wohelo been built, and its use of symbols is, perhaps, more than anything else, a working and ever-present declaration of the spiritual values inherent in all the humblest phases of our everyday life in the world. (8.)

Detail: "Mermaid Study : Submerged": Gelatin silver print: ca. 1914 or before: by Charlotte Vetter Gulick: image: 8.4 x 10.8 cm: mount: 16.7 x 22.7 cm. : reproduced as final photo for article "The Mermaid" A SERIES OF PHOTOGRAPHS BY MRS. LUTHER HALSEY GULICK: in Everybody’s Magazine: New York: August, 1914: p. 232: from: PhotoSeed Archive

Detail: "Mermaid Study : Submerged": Gelatin silver print: ca. 1914 or before: by Charlotte Vetter Gulick: image: 8.4 x 10.8 cm: mount: 16.7 x 22.7 cm. : reproduced as final photo for article "The Mermaid" A SERIES OF PHOTOGRAPHS BY MRS. LUTHER HALSEY GULICK: in Everybody’s Magazine: New York: August, 1914: p. 232: from: PhotoSeed Archive

Five years before this philosophy was written, in 1910, Charlotte Gulick, known by her symbolic Indian name at the Wohelo camp as Hiiteni, which translated to “Life, more life”, came up with the idea for the Camp Fire Girls movement. An organization for girls much as the Boy Scouts of America was structured for boys, and coincidentally founded the same year, Camp Fire Girls promoted all the values she and her husband had already been teaching at their earlier camp at Gales Ferry and at Wohelo:

”The idea originated in the mind of Mrs. Gulick, and was at once indorsed by Dr. Gulick, who believes it to be logical and necessary to proper development of girls amid the changing conditions of our National life.” (9.)

Left: detail: photo by "David": title: "Portrait Instantané D'un Plongeur" ("Instant Portrait of a Diver") : photogravure plate XI by Paul Dujardin showing French underwater photography pioneer Louis Marie-Auguste Boutan (1859-1934) holding himself steady underwater: from: 1900 volume "La Photographie Sous-Marine et Les Progres de La Photographie" (The Progress of Underwater Photography) (between pp. 210-211) : Gallica: National Library of France online resource. Right: a modern-day mermaid: Nicole Marino plays the starring role in "The Little Mermaid" at Florida's Weeki Wachee Springs Waterpark. In 1947, former Navy frogman Newton Perry conceived of the idea of using an air hose and perfected "hose breathing" here. Culturally, mermaids are a tourist attraction, and have entered the popular imagination through films like "The Incredible Mr. Limpet" starring Don Knotts. (1964): 1999 photo by David Spencer/The Palm Beach Post

Left: detail: photo by "David": title: "Portrait Instantané D'un Plongeur" ("Instant Portrait of a Diver") : photogravure plate XI by Paul Dujardin showing French underwater photography pioneer Louis Marie-Auguste Boutan (1859-1934) holding himself steady underwater: from: 1900 volume "La Photographie Sous-Marine et Les Progres de La Photographie" (The Progress of Underwater Photography) (between pp. 210-211) : Gallica: National Library of France online resource. Right: a modern-day mermaid: Nicole Marino plays the starring role in "The Little Mermaid" at Florida's Weeki Wachee Springs Waterpark. In 1947, former Navy frogman Newton Perry conceived of the idea of using an air hose and perfected "hose breathing" here. Culturally, mermaids are a tourist attraction, and have entered the popular imagination through films like "The Incredible Mr. Limpet" starring Don Knotts. (1964): 1999 photo by David Spencer/The Palm Beach Post

Today, the history of the Gulick’s shared virtues of work, health and love continue on in the summer operation of their Maine camps. In a promotional 1919 silent film on Wohelo released a year before women in the United States had the Constitutional protection of the right to vote, these changing conditions of America’s National life for young women were on display. Seated in teams of coordinated paddlers in three large over-sized canoes on Lake Sebago, the ideals of resourcefulness in working together shown in the film remains an ideal for young women still valued today.

Detail: "Mermaid Sunbathing " ("Kitty" Gulick) : Gelatin silver print: ca. 1914 or before: by Charlotte Vetter Gulick: image: 7.3 x 10.8 cm: mount: 17.0 x 22.5 cm. : In this photo, a figure study of Katharine "Kitty" Gulick by her mother, "Ki-lo-des-ka" sunbathes next to granite boulders on the Sebago Lake shoreline in Maine.: from: PhotoSeed Archive

Detail: "Mermaid Sunbathing " ("Kitty" Gulick) : Gelatin silver print: ca. 1914 or before: by Charlotte Vetter Gulick: image: 7.3 x 10.8 cm: mount: 17.0 x 22.5 cm. : In this photo, a figure study of Katharine "Kitty" Gulick by her mother, "Ki-lo-des-ka" sunbathes next to granite boulders on the Sebago Lake shoreline in Maine.: from: PhotoSeed Archive

Much like these photos of Ki-lo-des-ka the mermaid, “her yellow hair glinting golden in the sunshine” (10.) reveal beauty to us in the physical form, lines from a poem by Ralph Waldo Emerson cited by the amateur photographer Charlotte Gulick after she mastered the art of water diving at the age of 35 brings forth a desire in the human spirit to symbolically enter the depths as well:

”To vision profounder

Man’s spirit must dive.“ (11.)

Notes:

1. Louis Marie-Auguste Boutan. (1859-1934) Boutan used specially-designed underwater camera housings, publishing his research conducted from 1892-1900 for a large audience in the 1900 volume “La Photographie Sous-Marine et Les Progres de La Photographie”. (The Progress of Underwater Photography)

2. from: The Mermaid: in: Everybody’s Magazine: New York: The Ridgway Company Publishers: August, 1914: p. 225

3. Ibid: pp. 225-232

4. 1870 U.S. Census. Gulick changed her name to Charlotte sometime after 1900 but was known as “Lottie”

5. Gulick background: Margaret R. and Dennis S. O’Leary: Adventures at Wohelo Camp - Summer of 1928: 2011: iUniverse: p. 24

6. 1921 poster of Luther Halsey Gulick: Makers of American Ideals poster issued by the National Child Welfare Association: Springfield College Digital online resource accessed Oct., 2014

7. background: Camp Timanous website accessed Oct., 2014. Owned by the Suitor family since the 1930’s, the camp was originally founded by Luther Halsey Gulick in 1917, whose symbolic Indian name Timanous- was “Guiding Spirit”. In the introduction to the 1915 Sebago-Wohelo Camp Fire Girls volume, Charlotte Gulick states as many as 75 people camped together at Gales Ferry before Wohelo was established.

8. excerpt: Introduction: Mrs. Luther Halsey Gulick: Ethel Rogers: Sebago-Wohelo Camp Fire Girls: Battle Creek, MI: Good Health Publishing Company: 1915: pp. 22-23

9. excerpt: Girls Take up the Boy Scout Idea and Band Together: Edward Marshall: in: The New York Times: March 17, 1912

10. Sebago-Wohelo Camp Fire Girls: p. 94

11. Ibid: p. 22

✻ : and of course I’m happy to be corrected

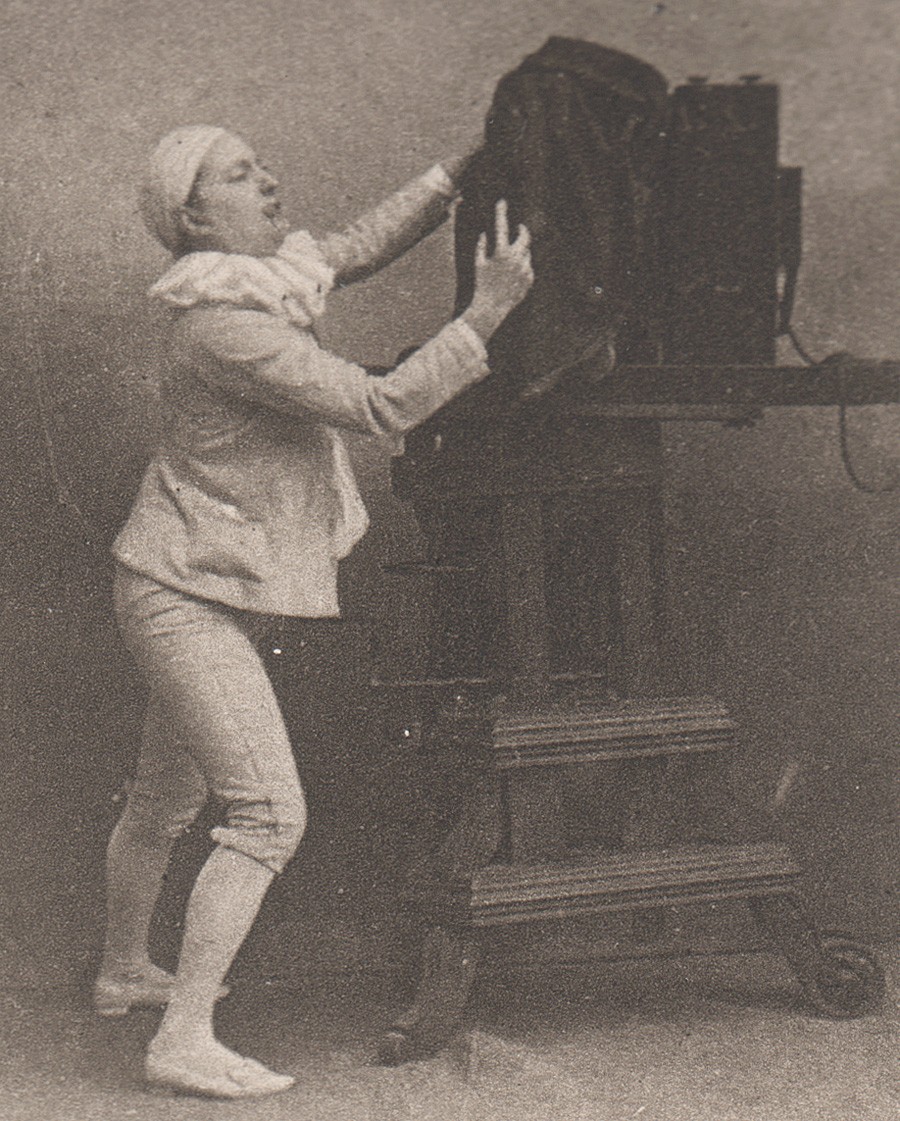

The Permanence of Disruption

Posted August 2014 in History of Photography, Painters|Photographers, Photography, Publishing, Significant Photographers

By all accounts, Scotsman David Octavius Hill, (1802-1870) Secretary of the Royal Scottish Academy of Fine Arts in Edinburgh, was an accomplished landscape painter. Thankfully, for the nascent medium of photography beginning around 1843, he is not remembered for that. Blame the Disruption, if you will.

Detail: 1868: Artist David Octavius Hill with sketchpad at top; Photographer Robert Adamson behind wooden box camera at bottom. : Thomas Annan: vintage carbon copy photograph after D.O. Hill painting: "The Disruption of the Church of Scotland"completed 1866: original: (13.5 x 31.4 cm | 34.4 x 41.4 cm ) : from: PhotoSeed Archive

Detail: 1868: Artist David Octavius Hill with sketchpad at top; Photographer Robert Adamson behind wooden box camera at bottom. : Thomas Annan: vintage carbon copy photograph after D.O. Hill painting: "The Disruption of the Church of Scotland"completed 1866: original: (13.5 x 31.4 cm | 34.4 x 41.4 cm ) : from: PhotoSeed Archive

Disruption with a capitol D? He didn’t know it at the time, but when the freethinking Hill, a devout churchman seen above in detail in his own painting, sketchpad in hand, attended what became known as the Disruption: or, the historical occasion of Scottish religious free will known as the First General Assembly of the Free Church of Scotland signing the Act of Separation and Deed of Demission at Edinburgh’s Tanfield Hall, the artistic potential of photography would soon stake its’ own claim among the arts.

The Scots are Coming

Admittedly, the focus of this website doesn’t claim any great insights into the evolution of early photography, with the exception that certain photographers, those being the team of Hill and fellow Scotsman Robert Adamson, (1821-1848) popularly known as “Hill & Adamson”, are profoundly important to our understanding of artistic developments in relation to photography that came later in the 19th Century. Similar to the concept of how precedent by itself can build a case in the courtroom or in the more democratic court of public opinion, the reach of Hill & Adamson through their artistic achievement, especially in portraiture, impacted greatly the later working methods of many photographers and in particular, the eventual achievement of two fellow Scots who came into their orbit: Thomas Annan and his son James Craig Annan beginning around 1865 and in the early 1890’s.

As for that “Disruption” in relation to Hill’s completion 23 years later of an over-sized painting commemorating the event, the decision to separate from the accepted order gave former Church of Scotland congregations the freedom from central Church control to choose their own ministers, among other religious freedoms. For this alone, photography’s potential was nicely summed up in the London Art-Union journal in late 1869:

To photography Mr. Hill, soon after its discovery, about the year 1843, gave much attention, and we shall not be wrong in assigning him the credit of giving to the process its first artistic impetus; and, in conjunction with his friend, Mr. R. Adamson, of having produced many specimens of the Talbotype as yet unsurpassed for high artistic qualities. (1.)

Example of vintage mounted salt print from calotype negative:(trimmed) : ca. 1845-1855: unknown photographer and location: detail from facade of English or Continental church building: ca. 1845-55: 12.8 x 8.8 | 24.9 x 19.9 cm: from PhotoSeed Archive

Example of vintage mounted salt print from calotype negative:(trimmed) : ca. 1845-1855: unknown photographer and location: detail from facade of English or Continental church building: ca. 1845-55: 12.8 x 8.8 | 24.9 x 19.9 cm: from PhotoSeed Archive

Thank the Calotype

Because the patent restricting Englishman William Henry Fox-Talbot’s 1841 invention of the Calotype process did not apply in Scotland, Hill & Adamson were able to exploit it to full potential. I’ve uploaded an example above, which in viewable form is technically known as a salted paper print from a calotype negative, for comparison. A survivor showing a bit of Gothic architectural detail, it was most likely done between 1845-1855 and found tucked between the pages of this archive’s copy of the aforementioned monthly Art-Union from 1846: the first magazine in history to publish (6000 copies) an example of a Talbotype “Sun Pictures” process calotype.

For a relatively clear understanding of what this early, yet cumbersome two-step process was, former George Eastman House Senior Curator of Photography William R. Stapp wrote in the pages of Image magazine from 1993 on the occasion of a seminal show of original Hill & Adamson calotypes held by the institution:

Calotypes are made on paper. The process requires the photographer to sensitize a sheet of good quality writing paper by brushing it with successive solutions of silver nitrate, potassium iodide, gallic acid, and silver nitrate. After being dried in the dark, the sensitized paper is loaded in the camera; after an exposure of several minutes, the negative is developed by brushing the paper with a solution of gallic acid and silver nitrate, fixed in a bath of sodium thiosulfate (“hypo”) to remove unexposed silver salts, and washed. When dried, this typically dense and contrasty negative is used to make a positive print on so called “salted paper,” which the photographer also has to prepare. This time a sheet of the same good quality writing paper is soaked first in a solution of sodium chloride (ordinary table salt, hence the term “salted paper”), then in a solution of silver nitrate, to produce the halide silver chloride. After it has been dried in the dark, the now light-sensitive salted paper is exposed to the negative in strong sunlight until the image is printed-out on it in deep orange hues. The resulting positive print is fixed in hypo, toned with gold chloride to a rich reddish-brown color, and washed to remove the residual chemistry. In all modern photographic materials, a transparent gelatin emulsion coated on the film or paper support contains the silver particles that form the image. Neither the calotype negative nor the calotype positive has an emulsion of any kind. The image resides literally within the fibers of the paper because the paper itself has been permeated with the photosensitive chemicals. A calotype print consequently incorporates the “tooth” (texture) of both the negative paper and the positive paper in its image. The print has a texture that is both visual and physical, which softens the image and mutes the rendition of detail. (2.)

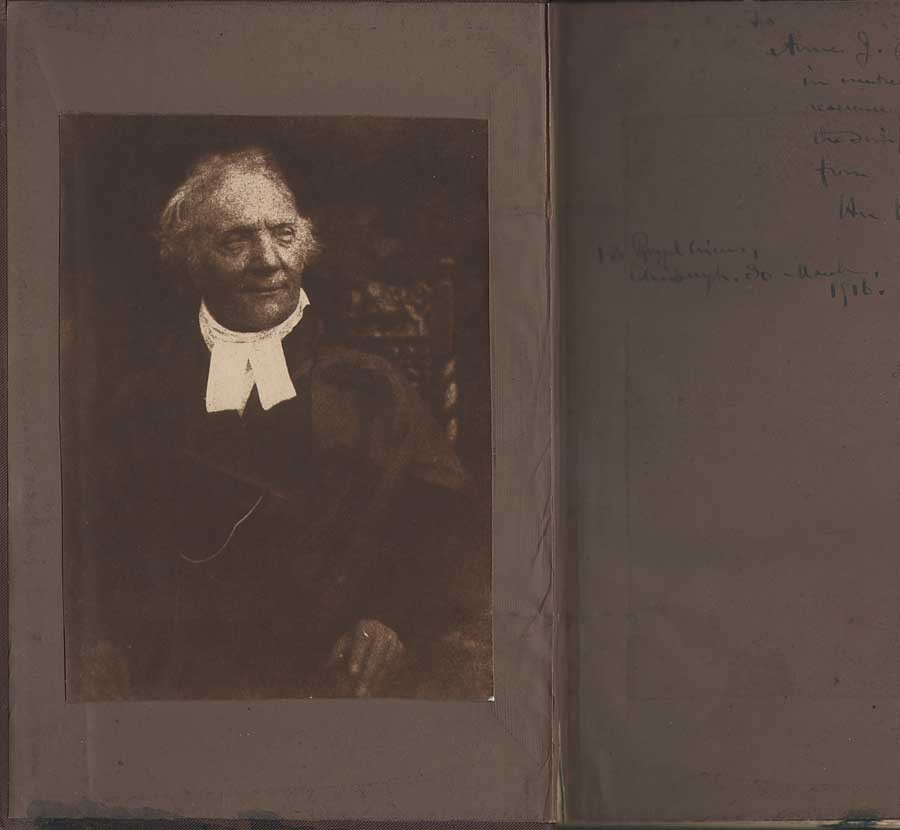

Pasted carbon print: ca. 1916: The Rev. Dr. Thomas Chalmers: (1780-1847) minister, social reformer, leader & first Moderator of the Free Church of Scotland Assembly, Principal of New College, Edinburgh.:15.2 x 11.1 cm: Jesse Bertram: after original ca. 1843 calotype by Hill & Adamson.: shown on opened, inside board cover to volume: "A Selection from the Correspondence of the late Thomas Chalmers, D.D. LL.D." : Edinburgh: Thomas Constable and Co. : 1853: from PhotoSeed Archive

Pasted carbon print: ca. 1916: The Rev. Dr. Thomas Chalmers: (1780-1847) minister, social reformer, leader & first Moderator of the Free Church of Scotland Assembly, Principal of New College, Edinburgh.:15.2 x 11.1 cm: Jesse Bertram: after original ca. 1843 calotype by Hill & Adamson.: shown on opened, inside board cover to volume: "A Selection from the Correspondence of the late Thomas Chalmers, D.D. LL.D." : Edinburgh: Thomas Constable and Co. : 1853: from PhotoSeed Archive

Activism, and a bit of Fate

As fate would have it, one of those involved with the Scottish Free Church movement was Fox-Talbot correspondent Sir David Brewster. A friend of “Disruption” general assembly moderator, the Rev. Dr. Thomas Chalmers, (1780-1847) who was a minister, social reformer and evangelical orator of high renown chiefly responsible for the secession from the established Church, Brewster early on had learned the Calotype process from his friend Talbot. Teaming with Saint Andrews University chemistry professor John Adamson, they in turn taught it to Adamson’s younger brother Robert Adamson in 1842 after he had moved to Edinburgh.

And the rest they say is history. With Brewster also present at the assembly signing with Hill, he in turn suggested the new process to the painter as a way to solve the dilemma of accurately portraying the hundreds of clergy and others present at the “Disruption” for posterity.

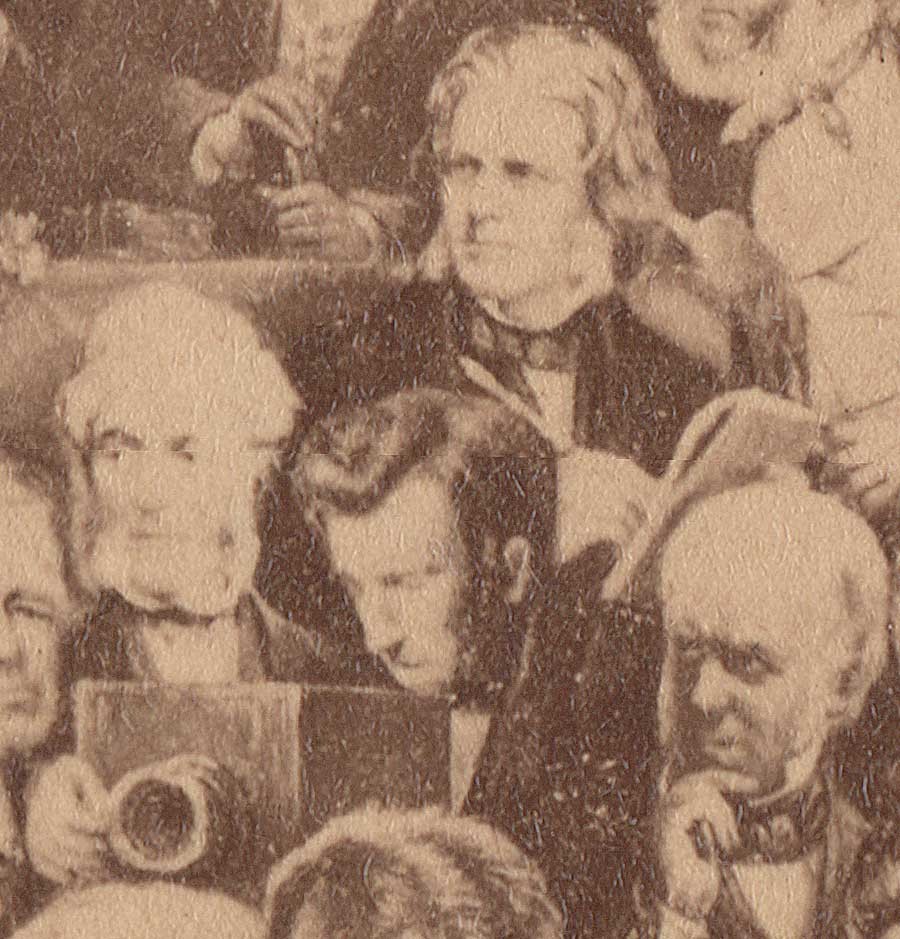

Detail: 1868: far right: Rev. Dr. Thomas Chalmers: Free Church of Scotland moderator along with major figures left to right: Scottish photography pioneer Sir David Brewster, (wearing spectacles looking down at book) Rev. Robert Lorimer, Rev. John Forbes, Dr. David Welsh: undivided Church of Scotland moderator holding a copy of May 18, 1843 church protest that was never answered, Dr. John Fleming, Chalmers. : Thomas Annan: vintage carbon copy photograph after D.O. Hill painting: "The Disruption of the Church of Scotland"completed 1866: original: (13.5 x 31.4 | 34.4 x 41.4 cm ) : from PhotoSeed Archive

Detail: 1868: far right: Rev. Dr. Thomas Chalmers: Free Church of Scotland moderator along with major figures left to right: Scottish photography pioneer Sir David Brewster, (wearing spectacles looking down at book) Rev. Robert Lorimer, Rev. John Forbes, Dr. David Welsh: undivided Church of Scotland moderator holding a copy of May 18, 1843 church protest that was never answered, Dr. John Fleming, Chalmers. : Thomas Annan: vintage carbon copy photograph after D.O. Hill painting: "The Disruption of the Church of Scotland"completed 1866: original: (13.5 x 31.4 | 34.4 x 41.4 cm ) : from PhotoSeed Archive

Twenty-three years later, most likely with the help of Hill’s second wife Amelia Paton, (1820-1904) a sculptress, the Disruption painting, measuring in finished at over 11 feet by 5 feet, was ready for public display. And this is where it gets interesting for the career of Thomas Annan (1829–1887) and much later, his son James Craig Annan. (1864-1946) The decision to copy the painting for a mass audience was never in doubt for Hill, a man well-connected with the Scottish publishing trade who was born into it; his father being a bookseller and publisher. Hill had even learned the art of lithography from an early age, using it in the reproduction of his own work as a landscape painter for 20 years.

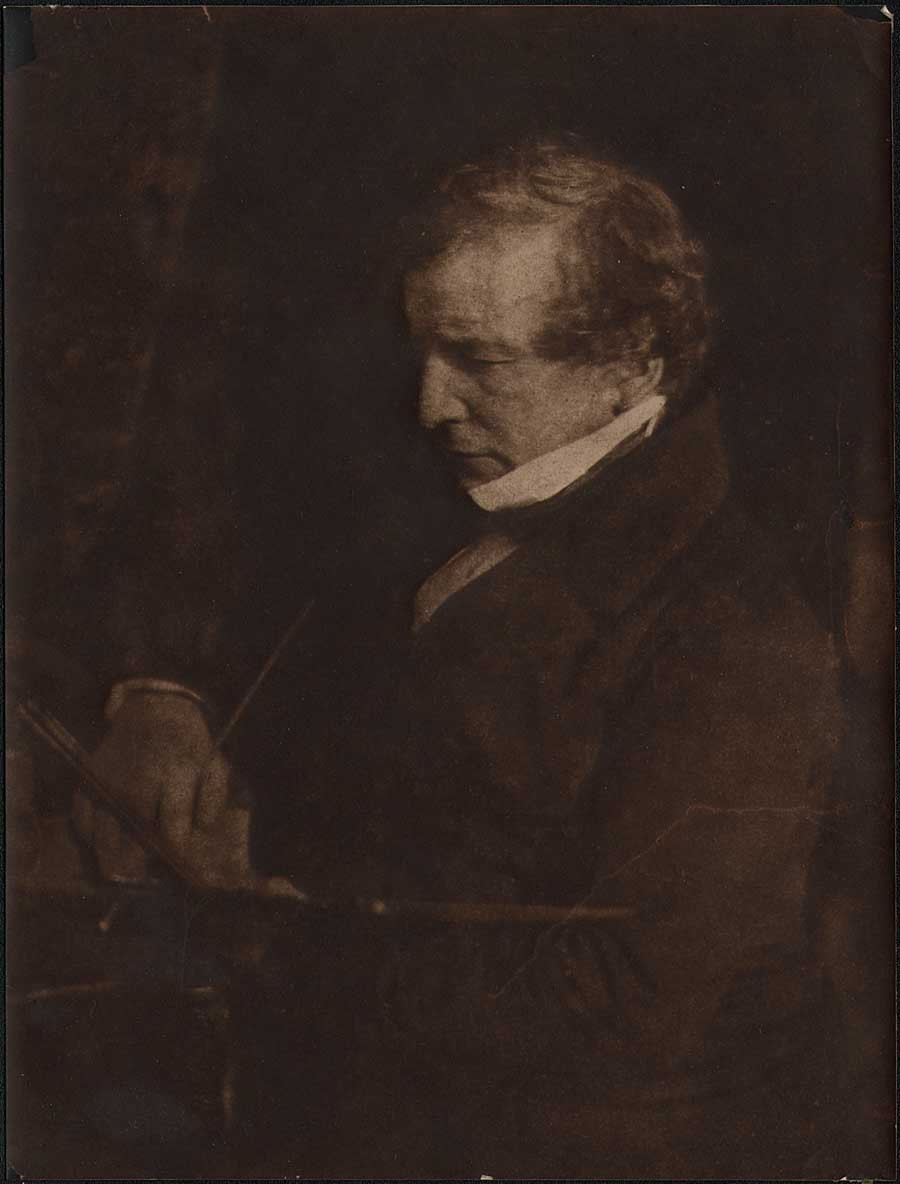

Carbon print: ca. 1879 - 1881 : William Etty, R.A. (English painter: 1787-1849) : Thomas Annan or James Craig Annan: after original 1844 calotype paper negative by Hill & Adamson: 18.5 x 14.0 cm: former collection: Exeter Camera Club: from PhotoSeed Archive

Carbon print: ca. 1879 - 1881 : William Etty, R.A. (English painter: 1787-1849) : Thomas Annan or James Craig Annan: after original 1844 calotype paper negative by Hill & Adamson: 18.5 x 14.0 cm: former collection: Exeter Camera Club: from PhotoSeed Archive

In 1865, shortly before his masterwork was finished, Hill made the acquaintance of Annan by reputation through his brother Alexander’s art gallery in Edinburgh. Annan’s copy paintings had been displayed there, for he had already made a name for himself in this line of work as early as 1862, producing fine copies of artwork for the Glasgow Art Union. These Art Unions “were lotteries connected with the major art exhibitions; the successful subscribers won paintings, and every subscriber received an engraving.” (3)

A commission resulted between Hill and Annan to copy Hill’s Disruption masterwork, a canvas that unfortunately- as opposed to the hundreds of Hill & Adamson calotypes used for reference works in its’ creation and now considered masterpieces of the photographic art-did not equate it to a masterpiece itself. Annan employed for this task an improved permanent carbon photographic process, using Joseph Wilson Swan’s 1864 patent carbon tissue to reproduce copies of the “Disruption” after purchasing the Scottish rights from him in 1866. (4.)

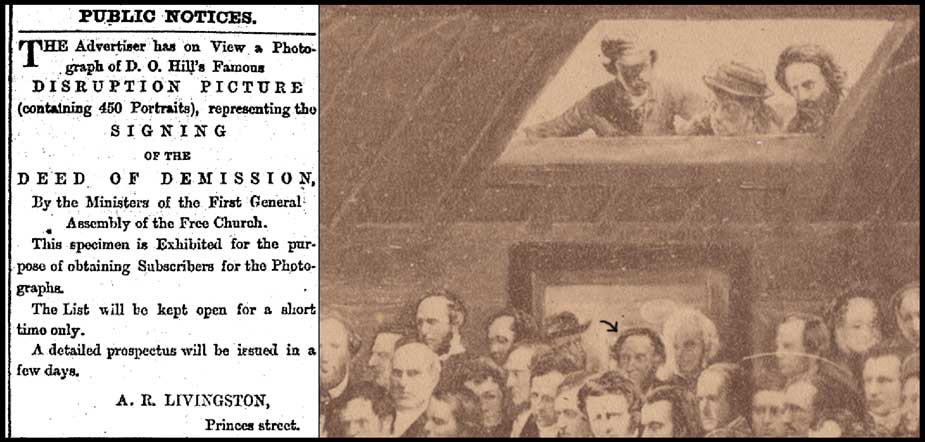

Left: 1868: advertisement: New Zealand bookseller A.R. Livingston's solicitation for Thomas Annan carbon photo of "Disruption Picture" completed 1866 by D.O. Hill: published in Otago Daily Times. Right: 1868: Detail: black arrow pointing to Thomas Annan standing in doorway painted as part of "Disruption" painting (another account states Annan is at left of this figure wearing hat) : Thomas Annan: vintage carbon copy photograph after D.O. Hill painting: "The Disruption of the Church of Scotland"completed 1866: original: (13.5 x 31.4 | 34.4 x 41.4 cm ) : from PhotoSeed Archive

Left: 1868: advertisement: New Zealand bookseller A.R. Livingston's solicitation for Thomas Annan carbon photo of "Disruption Picture" completed 1866 by D.O. Hill: published in Otago Daily Times. Right: 1868: Detail: black arrow pointing to Thomas Annan standing in doorway painted as part of "Disruption" painting (another account states Annan is at left of this figure wearing hat) : Thomas Annan: vintage carbon copy photograph after D.O. Hill painting: "The Disruption of the Church of Scotland"completed 1866: original: (13.5 x 31.4 | 34.4 x 41.4 cm ) : from PhotoSeed Archive

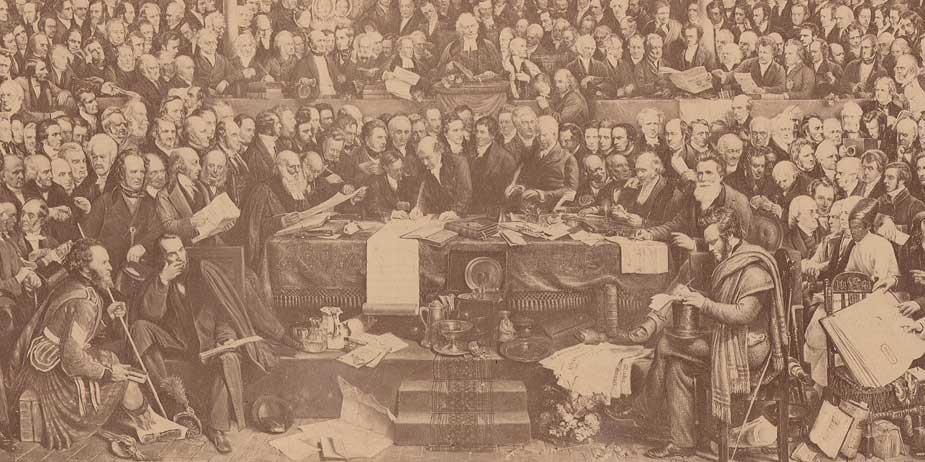

In addition to several detail photos of the painting included with this post, a mounted carbon copy photograph by Annan published in 1868 for the 25th anniversary of the signing of the Act of Separation and Deed of Demission can be seen in our archive here. For those adventurous enough to decipher names and titles of some of those making up the sea of faces in the painting, partly seen below, a fascinating, yet tricky key to some of the major figures can be found here. This was published as part of the 1943 centenary volume The Disruption Picture: A Memorial of the First General Assembly of the Free Church of Scotland by Donald MacKinnon. (5.)

Detail: 1868: At center of table, the Rev. Dr. Patrick MacFarlan (1781-1849) of Greenock is first to sign the "Deed of Demission", "resigning the highest living in the Church of Scotland at the time", said to be £ 1000.00 annually, which commemorated the establishment of the Free Church of Scotland: Thomas Annan: vintage carbon copy photograph after D.O. Hill painting: "The Disruption of the Church of Scotland"completed 1866: original: (13.5 x 31.4 cm | 34.4 x 41.4 cm ) : from PhotoSeed Archive

Detail: 1868: At center of table, the Rev. Dr. Patrick MacFarlan (1781-1849) of Greenock is first to sign the "Deed of Demission", "resigning the highest living in the Church of Scotland at the time", said to be £ 1000.00 annually, which commemorated the establishment of the Free Church of Scotland: Thomas Annan: vintage carbon copy photograph after D.O. Hill painting: "The Disruption of the Church of Scotland"completed 1866: original: (13.5 x 31.4 cm | 34.4 x 41.4 cm ) : from PhotoSeed Archive

Thomas Annan, Documentarian

With Hill’s work complete, Thomas Annan’s professional career was starting to hit full stride, especially after his success with the Disruption commission. In 1868, the same year a version of this carbon photo was published, (6.) Annan undertook a new commission from the City of Glasgow Improvements Trust that when first published as a series of around 35 albumen prints in 1872, became known as The Old Closes & Streets of Glasgow. As previously outlined in my essay written in 2006 for the Luminous Lint website, Annan’s photographs taken between 1868-1871 are among the earliest done specifically for a record of slum housing conditions prior to urban renewal and as such are an important milestone in the history of documentary photography. (7)

1868: vintage hand-pulled photogravure: "Close No. 193 High Street": Thomas Annan: from: "The Old Closes & Streets of Glasgow" - photographs taken for the City of Glasgow Improvements Trust : 22.2 x 18.1 | 38.0 x 28.5 cm: 1900: gravure from original collodion glass plate by James Craig Annan: Glasgow: plate #9 from James MacLehose & Sons limited edition of 100: from PhotoSeed Archive

1868: vintage hand-pulled photogravure: "Close No. 193 High Street": Thomas Annan: from: "The Old Closes & Streets of Glasgow" - photographs taken for the City of Glasgow Improvements Trust : 22.2 x 18.1 | 38.0 x 28.5 cm: 1900: gravure from original collodion glass plate by James Craig Annan: Glasgow: plate #9 from James MacLehose & Sons limited edition of 100: from PhotoSeed Archive

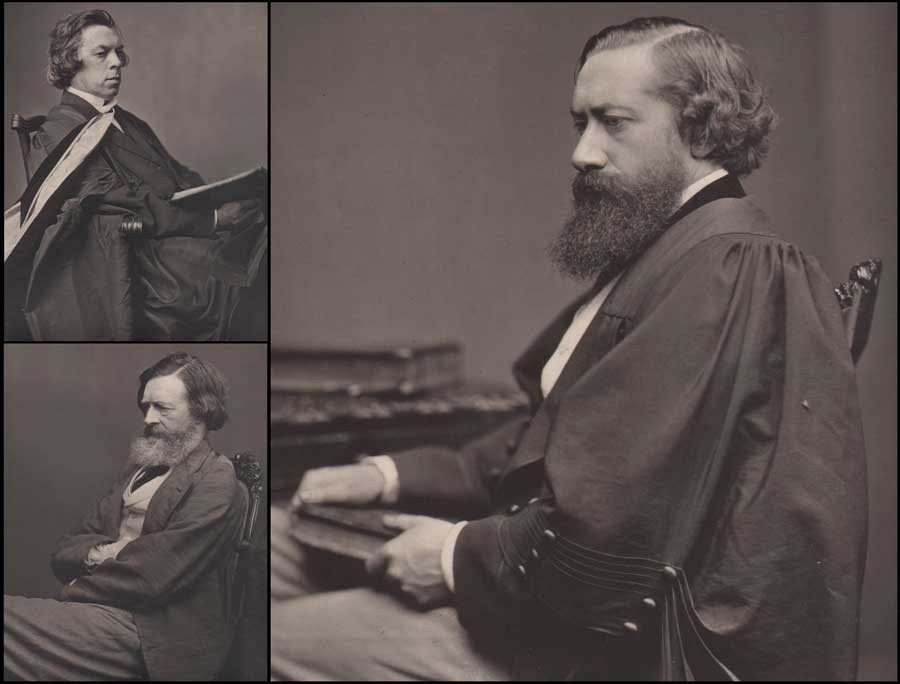

Perhaps knowing her husband’s photographic legacy might be carried on, Amelia Paton bequeathed to Annan “a large collection of calotypes and the portrait lens used by Hill and Adamson” after Hill’s death in 1870. (8.) Speculation he used this very lens for portraits taken soon after for his illustrated volume the Memorials of the Old College of Glasgow, (1871) with examples seen in this post, are an intriguing insight raised by Sara Stevenson in her biography of Annan. (9.) Proportionally, individual portraits taken by Hill & Adamson in the 1840’s compared with those by Annan of the professors from the Glasgow volume and are very similar. However, Annan had the advantage of using the collodion process as opposed to calotype, with the increase of sensitivity of these plates lending a sharpness to his work not possible as movement was often the inevitable result of the slower 2-3 minute exposures required for the older process.

A comparison showing the softness, beauty and masterful composition of a later generation carbon print portrait of English painter William Etty (1787-1849) done ca. 1843 by Hill and Adamson can be seen with this post along with portraits by Annan taken around 1870. These include the striking portrait of professor and theologian John Caird (1820-1898) that reveal compositional similarities between the photographers nearly 30 years apart. With the archival benefit of Annan printing his efforts in permanent carbon, it’s also amusing to see exposure times, although shorter than calotype, did not prevent him in at least one case from seizing the moment in order to permanently memorialize his subject and another unwitting one: a rather large housefly clinging to academic robes worn by University of Glasgow English Language and Literature Professor John Nichol.

1871: Thomas Annan: mounted carbon portraits from"Memorials of the Old College of Glasgow"(each cropped) : all portraits 21.5 x 16.4 | 36.5 26.0 : upper left: Professor of Divinity John Caird (1820-1898) : lower left: Professor of Greek Edmund Law Lushington (1811-1893) : right: Regius Professor of English Language and Literature John Nichol (1833-1894) (note housefly on academic robe at right below chair back) : from PhotoSeed Archive

1871: Thomas Annan: mounted carbon portraits from"Memorials of the Old College of Glasgow"(each cropped) : all portraits 21.5 x 16.4 | 36.5 26.0 : upper left: Professor of Divinity John Caird (1820-1898) : lower left: Professor of Greek Edmund Law Lushington (1811-1893) : right: Regius Professor of English Language and Literature John Nichol (1833-1894) (note housefly on academic robe at right below chair back) : from PhotoSeed Archive

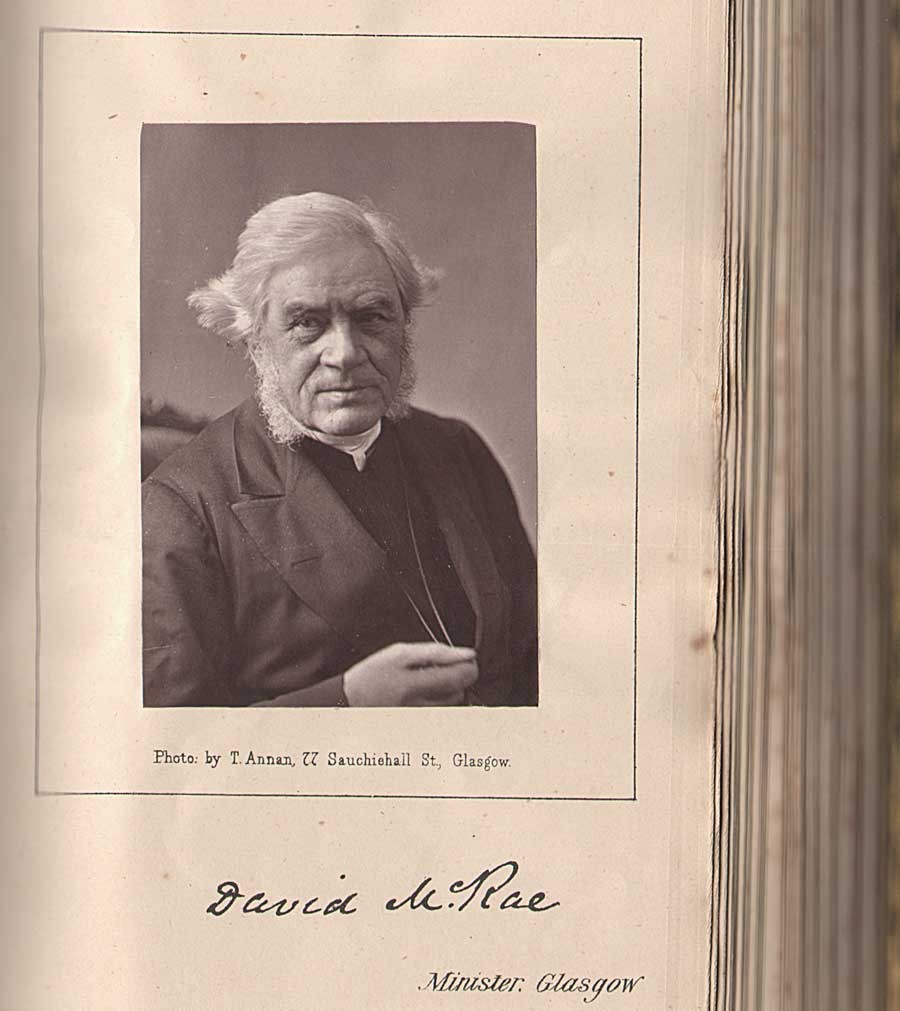

Besides University professors, Annan did many fine portraits of Free Church of Scotland ministers in addition to ministers, elders and missionaries affiliated with the United Presbyterian Church. A unique album of these portraits, reproduced in Woodburytype, is held by this archive, with several appearing in the 1875 Annan published volume Historical Notices of the United Presbyterian Congregations in Glasgow. As a businessman running a commercial studio, Annan marketed many of these images, often as variants, in the carte de visite format. The following is a listing of Annan’s Scotland studios with dates supplied by Peter Stubbs of the EdinPhoto web site:

202 Hope Street, Glasgow: 1862-72

77 Sauchiehall St. Glasgow: 1873-74

153 Sauchiehall St. Glasgow: 1875-91

75 Princes St. Edinburgh: 1876-82

1873-74: Rev. David McRae of Glasgow: (a leading temperance movement leader from the 1850-70's) mounted Woodburytype portrait with facsimile autograph: Thomas Annan: 8.3 x 5.6 | 19.4 x 10.5 cm : from unique folio album of nearly 60 Woodburytype photographs taken ca. 1862-1882 by Thomas Annan and most likely John Annan of ministers, elders and missionaries affiliated with the United Presbyterian Church: from PhotoSeed Archive

1873-74: Rev. David McRae of Glasgow: (a leading temperance movement leader from the 1850-70's) mounted Woodburytype portrait with facsimile autograph: Thomas Annan: 8.3 x 5.6 | 19.4 x 10.5 cm : from unique folio album of nearly 60 Woodburytype photographs taken ca. 1862-1882 by Thomas Annan and most likely John Annan of ministers, elders and missionaries affiliated with the United Presbyterian Church: from PhotoSeed Archive

Coming full-circle: Learning Photogravure

In 1883, after purchasing the British rights to a new process of Photogravure invented by Czech artist Karl Klíc, (1841-1926) Thomas Annan and son James Craig Annan traveled to Vienna in order to personally learn its intricacies. As defined by our good friends over at Photogravure.com, Klíc’s 1879 refined process of “reproducing a photograph by printing on paper from an inked and etched copper plate” was a vast improvement over that of William Henry Fox Talbot’s 1858 patented Photoglyphic Engraving process. Thomas Annan was so smitten he wrote Klíc the following appreciation:

“I beg to express my entire satisfaction with your gravure process… The process itself is very valuable to a fine art publisher because of the beauty of the work and the crafted manner in which the plates are executed. With many thanks to me and my son I remain, Dear Sir, yours very truly” - Thomas Annan March 11, 1883 (10.)

Fittingly renamed the Talbot-Klíc Dust Grain Photogravure by Klíc, the process was soon fully embraced by Annan’s publishing concerns, T. & R. Annan and Sons of Glasgow, Hamilton and Edinburgh, who utilized photogravure for high-quality, fade-resistant and archival plates, mostly copies of original works of art, an established specialty. Soon, the new process, which involved the individual hand-pulling of plates from a copper-plate press, was further exploited and refined by the budding photographer James Craig Annan in the early 1890’s, whose original photographic negatives “from nature” during his travels to the Continent, particularly North Holland and Italy, were directly reproduced in gravure after an ongoing period of great experimentation and refinement.

Like his father Thomas, who reproduced and exhibited some of the Hill & Adamson calotypes in carbon during the 1870’s and early 80’s using his own refinements of Swan’s process, (11.) James Craig Annan fully embraced Talbot-Klíc gravure printing to reinterpret their landmark achievements in early pictorial portraiture as well as other studies including the fisherfolk of Newhaven near Edinburgh. In this regard, beginning as early as 1890, Annan produced a series of hand-pulled gravures re-photographed from the original Hill & Adamson paper calotype “negatives in the possession of Andrew Elliott.” (12.) Later in 1905, working as part of the T & R Annan firm of Glasgow, he produced a further series of 20 plates printed on Japan tissue. (13.) These copper plates were then re-used for a series of gravures published in Alfred Stieglitz’s Camera Work XI, (1905) XXVIII, (1909) and XXXVII, (1912) thereby introducing new generations to the masterful legacy left by Hill & Adamson.

1890-1912: "Girl in Straw Hat" (Miss Mary McCandlish) : vintage hand-pulled photogravure trimmed and mounted within cream paper folder: possibly a 1912 Camera Work proof: 21.5 x 15.9 |25.5 x 19.0 cm: James Craig Annan after original paper calotype ca. 1843-47 by Hill & Adamson: reproduced in CW XXXVII: originally in Margaret Harker Collection: from PhotoSeed Archive

1890-1912: "Girl in Straw Hat" (Miss Mary McCandlish) : vintage hand-pulled photogravure trimmed and mounted within cream paper folder: possibly a 1912 Camera Work proof: 21.5 x 15.9 |25.5 x 19.0 cm: James Craig Annan after original paper calotype ca. 1843-47 by Hill & Adamson: reproduced in CW XXXVII: originally in Margaret Harker Collection: from PhotoSeed Archive

I’ll end this lengthy post with an excerpt from an appreciation of D.O. Hill by James Craig Annan, who was fortunate to have met and been inspired by the artist when he was only six years old- the result of his father being an intimate friend of Hill. This was included as part of a larger essay he wrote on the Scottish pioneer for Camera Work XI, and he makes the strong case their achievement was a direct result of their portrait collaborations for the Disruption painting:

“Thus the partnership began which was to produce the noble and extensive series of portraits which for powerful characterization and artistic quality of uniformly high excellence have certainly never been surpassed and possibly not even rivaled by any other photographer. This may seem an extravagant appreciation of Hill’s work, but it has been arrived at after mature deliberation.” (14.)

-David Spencer

Notes:

1. British Artists: Their Style and Character: With Engraved Illustrations. : David Octavius Hill, R.S.A.: in: The Art-Journal: London: October 1, 1869: p. 317

2. William F. Stapp.: Hill and Adamson: Artists of the Calotype: from: Image: George Eastman House: Spring/Summer: Vol. 36: No. 1-2: 1993: p. 55

3. Sara Stevenson: Scottish Masters 12: Thomas Annan: National Galleries of Scotland: 1990: p. 5

4. After discussions with Hill, the copy photograph of the “Disruption“canvas was taken by Thomas Annan after he had ordered “a large Photographic Camera of the latest and most perfect construction” from Dallmeyer: in: 1866 Disruption prospectus by Hill: published in: Scottish Masters 12: p. 7

5. Alan Newble has thoughtfully, and no doubt, painstakingly, compiled the key as part of his website, with further insights on the historical importance of the Rev. Dr. Thomas Chalmers.

6. In correspondence between Annan and Hill in late December, 1865, Hill stated he wanted the Disruption painting reproduced in thousands of photographs in 3 separate sizes. “He (Hill) was hoping for prints half the size of the painting, and suggested that Annan make them in three parts, joining them together around the figures rather than in an arbitrary straight line.” : from: Hill & Annan letters: quoted in: Scottish Masters 12: pp. 6-7. Alas, Hill’s desires were trumped by technical limitation, with carbon prints supplied by Annan printed in 1866 in 3 sizes, as stated in the Photographic News of London: “Photographs of the picture will be issued in three sizes, ranging from 24 inches by 9 inches to 48 inches by 21 1/4 inches, at prices ranging from a guinea and a half to twelve guineas.”

7. The carbon print edition of Old Closes first appeared in 1877, with two later photogravure editions featuring 50 plates each printed by James Craig Annan published in 1900. Fine examples of the albumen prints from Old Closes can be found along with superb background on their making at the University of Glasgow Library special collections department online resource found here.

8. cited in Scottish Masters 12: p. 8

9. Ibid: p. 13

10. from: Photogravure.com online resource accessed August, 2014. While in Vienna under Klíc’s watchful eye, the Annans had produced a photogravure of Noel Paton’s painting of The Fairy Raid.

11. Scottish Masters 12: p. 8

12. David Octavius Hill & Robert Adamson: in: The Collection of Alfred Stieglitz: Weston Naef: New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art: p. 378. Elliott, (1830-1922) was a nephew of D.O. Hill

13. Ibid, p. 378

14. excerpt: David Octavius Hill, R.S.A. ⎯1802-1870.: J. Craig Annan: in: Camera Work XI: New York: edited and published by Alfred Stieglitz:1905: p. 18

Oh Say Can you See?

Posted July 2014 in History of Photography, Scientific Photography, Significant Photographs

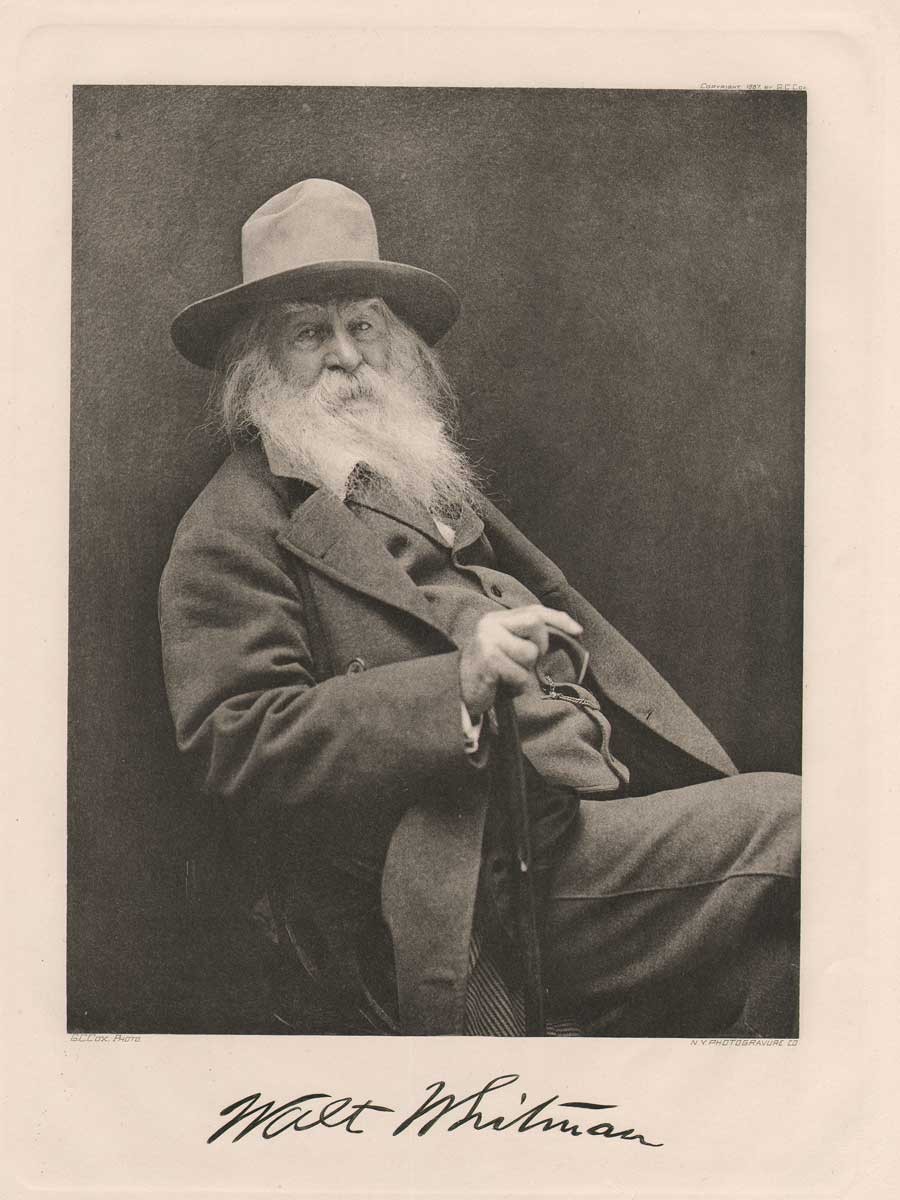

Walt Whitman certainly did. Just check out his eyeballs on this photograph taken in 1887 by George C. Cox for confirmation. Especially on this most personal of American holidays, the Fourth of July, the continuing birthday idea of our messy, evolving experiment of a democratic republic called the United States can never be said to be boring.

Detail: 1887: Walt Whitman-1819-1892 by George C. Cox: (portrait known as the "Laughing Philosopher") 23.9 x 18.8 cm | 45.2 x 33.3 cm: vintage large format, hand-pulled photogravure printed circa 1905-10 by the Photographische Gesellschaft in Berlin on Van Gelder Zonen plate paper. From: PhotoSeed Archive

Detail: 1887: Walt Whitman-1819-1892 by George C. Cox: (portrait known as the "Laughing Philosopher") 23.9 x 18.8 cm | 45.2 x 33.3 cm: vintage large format, hand-pulled photogravure printed circa 1905-10 by the Photographische Gesellschaft in Berlin on Van Gelder Zonen plate paper. From: PhotoSeed Archive

Need proof of his vision? - Whitman’s metaphorical call in this famous quote: “What is that you express in your eyes?” ; and response: “It seems to me more than all the print I have read in my life.”

You could say America’s poet (1819-1892) of the everyman didn’t need a camera, he was one. His genius of observation, something all great photographers possess, gave him the power to indelibly express his convictions. So when words flowed from his pen, they possessed the power of photographs, especially on the very idea of America in the aftermath of the Civil War:

"Walt Whitman Birthplace in 1903" (South Huntington, New York): by Ben Conklin: 1903: vintage albumen print: 20.3 x 25.2 cm from: PhotoSeed Archive: (Benjamin Sargent Conklin: 1873-1964)

"Walt Whitman Birthplace in 1903" (South Huntington, New York): by Ben Conklin: 1903: vintage albumen print: 20.3 x 25.2 cm from: PhotoSeed Archive: (Benjamin Sargent Conklin: 1873-1964)

from Leaves of Grass: intro to “Thoughts”:

Of these years I sing,

How they pass and have pass’d through convuls’d pains, as

through parturitions,

How America illustrates birth, muscular youth, the promise, the

sure fulfilment, the absolute success, despite of people-

illustrates evil as well as good,

The vehement struggle so fierce for unity in one’s-self;

How many hold despairingly yet to the models departed, caste,

myths obedience, compulsion, and to infidelity, … (1.)

"Walt Whitman" by George C. Cox: 1887. Hand-pulled photogravure published in periodical "Sun & Shade" New York: March, 1892: whole #43: N.Y. Photogravure Co.: 21.5 x 16.7 cm | 34.7 x 27.4 cm: from: PhotoSeed Archive

"Walt Whitman" by George C. Cox: 1887. Hand-pulled photogravure published in periodical "Sun & Shade" New York: March, 1892: whole #43: N.Y. Photogravure Co.: 21.5 x 16.7 cm | 34.7 x 27.4 cm: from: PhotoSeed Archive

But enough of the history lesson. Since most of us will never rise to the level of a Whitman in prose, photography as an art form is a comparably easy stretch. Speaking for myself as a young newspaper photographer in the mid 1980’s hunched over a light table editing film, an early mentor told me as long as a person’s eyes in the negative were tack sharp through the loupe, it was a “keeper”, and worthy of publication.

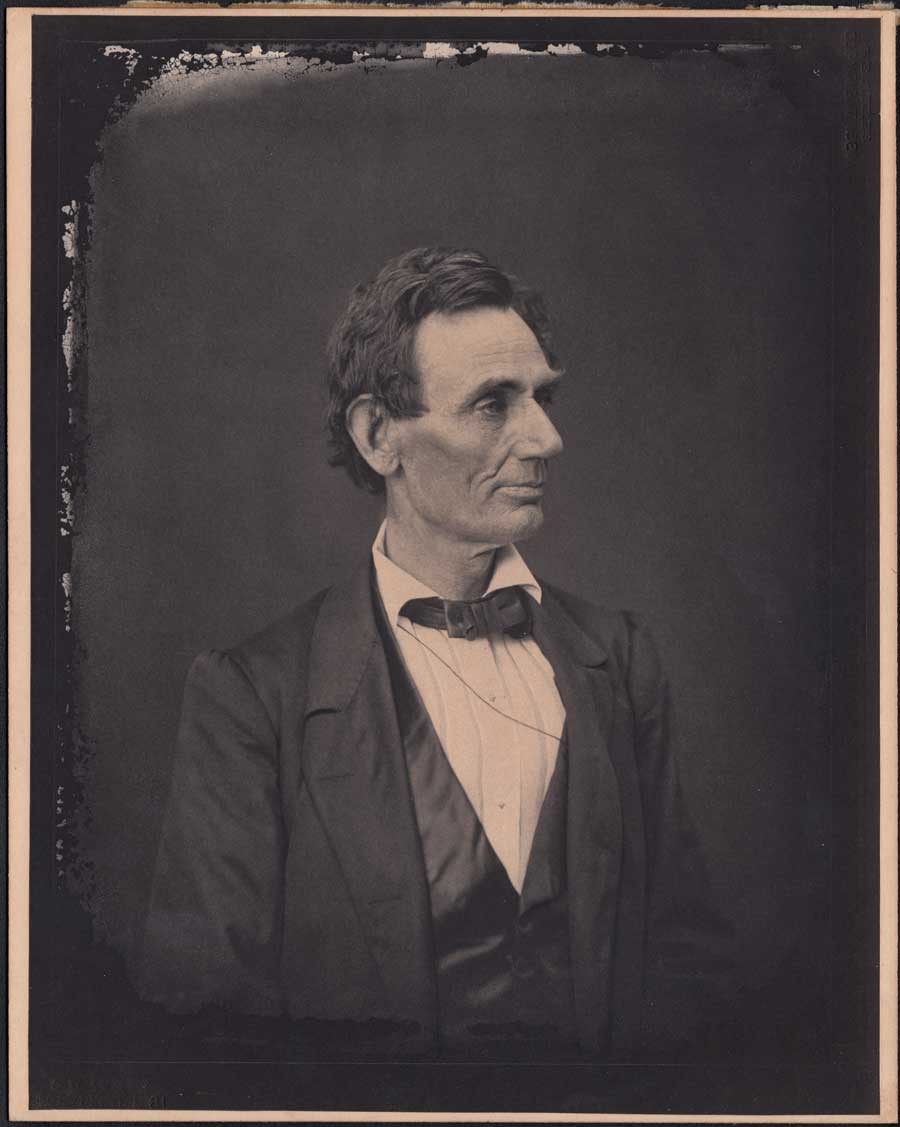

And so it was for my colleagues a century before my own light table revelation, but with the slow, fragile dry plates in use at the time a much greater technical challenge. In 1887, New York portrait photographer George Collins Cox (1851-1902) had the sitting of a lifetime in none other than Whitman. Strolling into his New York studio with oversized fedora, it was 22 years to the day no less on April 15th when American president Abraham Lincoln finally succumbed to an assassin’s bullet in 1865.

Abraham Lincoln by Alexander Hesler (1823-July 4th, 1895):taken in Springfield, Illinois on June 3, 1860: vintage platinum print © 1881 by George Bucher Ayres: print from late 1890's: Meserve #26|Ostendorf #26" One of the most famous Walt Whitman poems, "O Captain! My Captain!", eulogizing the death of this American president, was written by Whitman in 1865: from: PhotoSeed Archive

Abraham Lincoln by Alexander Hesler (1823-July 4th, 1895):taken in Springfield, Illinois on June 3, 1860: vintage platinum print © 1881 by George Bucher Ayres: print from late 1890's: Meserve #26|Ostendorf #26" One of the most famous Walt Whitman poems, "O Captain! My Captain!", eulogizing the death of this American president, was written by Whitman in 1865: from: PhotoSeed Archive

And he nailed it, as they say in America. Eyes tack sharp. The following historical account of the Whitman portrait sitting from the Charles E. Feinberg Collection at the Library of Congress gives a nice working account of Cox the photographer in action. A result of that session: the “Laughing Philosopher”, was the title Whitman declared as his favorite:

Detail: "Walt Whitman and the Butterfly" :1877(?):by W. Curtis Taylor of Broadbent & Taylor (Philadelphia): vintage hand-pulled vellum photogravure: 13.8 x 9.8 cm | 22.6 x 15.0 cm: from: Leaves of Grass II: The Complete Writings of Walt Whitman: New York:1902: Henry W. Knight:National Edition limited to 500 copies:"In fact, the "butterfly" was clearly a photographic prop now in the collections of the Library of Congress. The die-cut cardboard butterfly is imprinted with the lyrics to a John Mason Neale hymn and the word "Easter" in large capital letters."… What is not often noted is that the photo simply enacts one of the recurrent visual emblems in the 1860 edition of Leaves: a hand with a butterfly perched on a finger. …"The butterfly … represents, of course, Psyche, his soul, his fixed contemplation of which accords with his declaration: 'I need no assurances; I am a man who is preoccupied of his own soul.'"- The Walt Whitman Archive online resource- from: PhotoSeed Archive

Detail: "Walt Whitman and the Butterfly" :1877(?):by W. Curtis Taylor of Broadbent & Taylor (Philadelphia): vintage hand-pulled vellum photogravure: 13.8 x 9.8 cm | 22.6 x 15.0 cm: from: Leaves of Grass II: The Complete Writings of Walt Whitman: New York:1902: Henry W. Knight:National Edition limited to 500 copies:"In fact, the "butterfly" was clearly a photographic prop now in the collections of the Library of Congress. The die-cut cardboard butterfly is imprinted with the lyrics to a John Mason Neale hymn and the word "Easter" in large capital letters."… What is not often noted is that the photo simply enacts one of the recurrent visual emblems in the 1860 edition of Leaves: a hand with a butterfly perched on a finger. …"The butterfly … represents, of course, Psyche, his soul, his fixed contemplation of which accords with his declaration: 'I need no assurances; I am a man who is preoccupied of his own soul.'"- The Walt Whitman Archive online resource- from: PhotoSeed Archive

”On the morning of April 15th, 1887, George Cox took several photographs of Whitman, who was celebrating the success of his New York lecture on Lincoln, delivered the day before. Whitman recalls that “six or seven” photos were made during the session, but Whitman’s friend Jeannette Gilder, an observer of the session, said there were many more than that: ‘He must have had twenty pictures taken, yet he never posed for a moment. He simply sat in the big revolving chair and swung himself to the right or to the left, as Mr. Cox directed, or took his hat off or put it on again, his expression and attitude remaining so natural that no one would have supposed he was sitting for a photograph.“ (2.)

Detail: "Statue of Liberty at Night": Seneca Ray Stoddard: Hand-pulled photogravure published in periodical "Sun & Shade" New York: September, 1890: whole #25: N.Y. Photogravure Co.: 18.5 x 12.0 cm 35.2 cm x 27.6 cm: For many, the dream of America still holds true in the light, or darkness, of Lady Liberty's torch-even when viewed against the backdrop of the messy, evolving experiment of a democratic republic called the United States- one fully embraced in the writings of Walt Whitman. A technical description of this photograph copyrighted in 1889 by Stoddard: "Mr. Stoddard employed five cameras on this occasion, stationing them on the Steamboat Pier. A wire was stretched from the torch of the Statue to the mast of a vessel a considerable distance away. Placed on this wire, controlled by a pulley, was a cup containing one and one-half pounds of flash powder; an electric wire was connected with it, and at a given signal the current turned on, by the electrician in charge of the torch, the flash exploded and the exposure made." from: PhotoSeed Archive

Detail: "Statue of Liberty at Night": Seneca Ray Stoddard: Hand-pulled photogravure published in periodical "Sun & Shade" New York: September, 1890: whole #25: N.Y. Photogravure Co.: 18.5 x 12.0 cm 35.2 cm x 27.6 cm: For many, the dream of America still holds true in the light, or darkness, of Lady Liberty's torch-even when viewed against the backdrop of the messy, evolving experiment of a democratic republic called the United States- one fully embraced in the writings of Walt Whitman. A technical description of this photograph copyrighted in 1889 by Stoddard: "Mr. Stoddard employed five cameras on this occasion, stationing them on the Steamboat Pier. A wire was stretched from the torch of the Statue to the mast of a vessel a considerable distance away. Placed on this wire, controlled by a pulley, was a cup containing one and one-half pounds of flash powder; an electric wire was connected with it, and at a given signal the current turned on, by the electrician in charge of the torch, the flash exploded and the exposure made." from: PhotoSeed Archive

1. from “Thoughts” Leaves of Grass II: The Complete Writings of Walt Whitman: New York:1902: Henry W. Knight, publisher: National (limited) Edition: p. 275

2. excerpt: Walt Whitman Archive online resource accessed July, 2014

What the Heck? Solved!

Posted June 2014 in New Additions

Update: Solved! See below. Our original post from June, 2014:

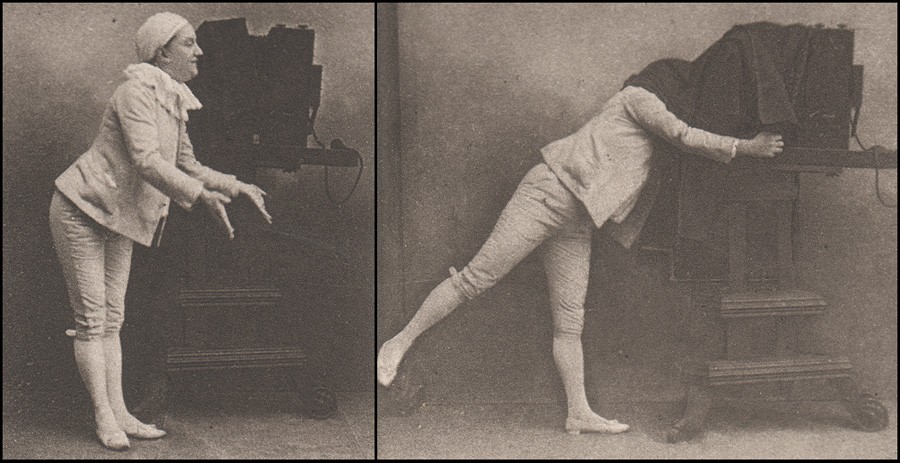

Sometimes, scratching your head does make sense. Especially when encountering a photograph such as this. I wish I could elaborate beyond my first instinct, which is that the subject resembles some kind of shrunken head with an extremely bad hair day.

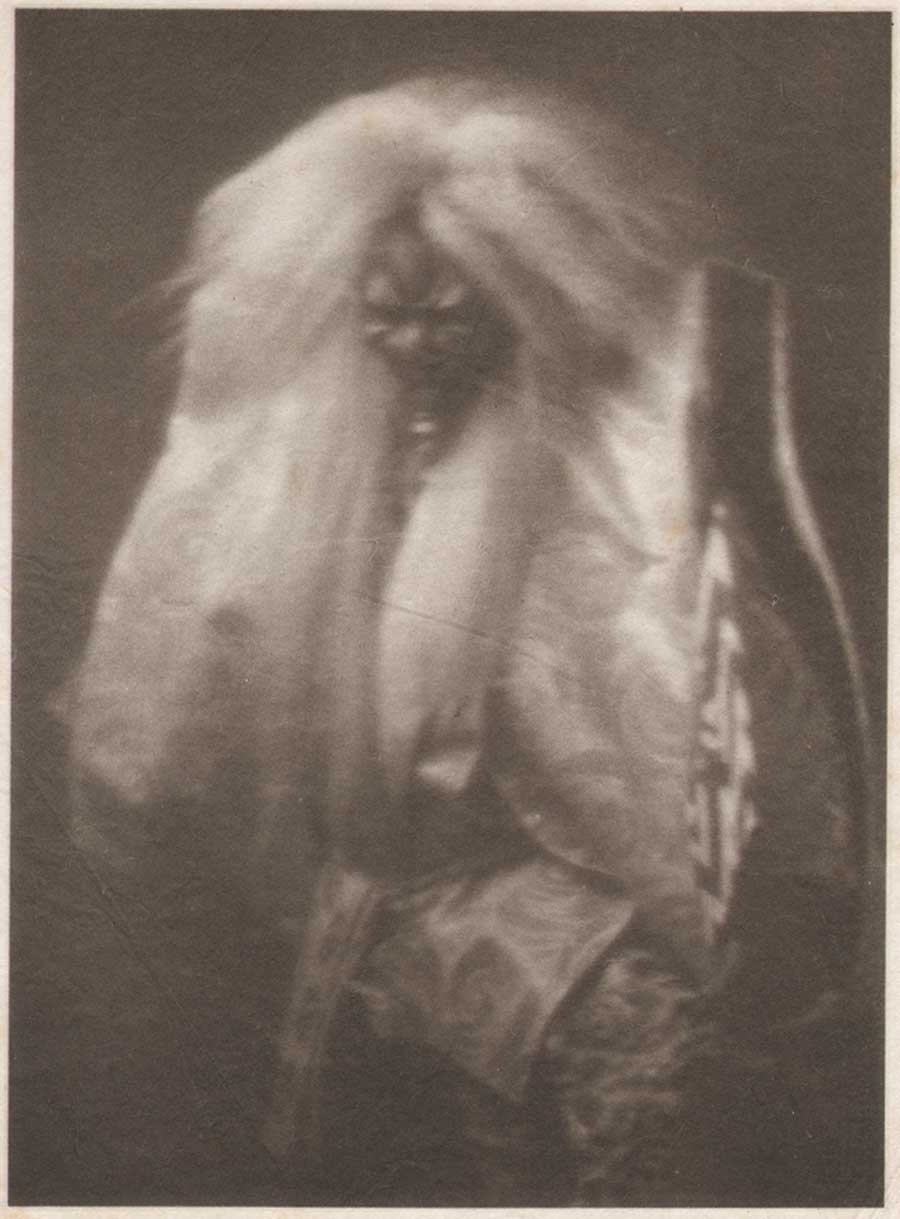

"Asian Mask?": cropped to image margins: (19.6 x 14.4 cm | 27.0 x 19.6 cm) Japanese tissue gravure: 1900-1920: from: PhotoSeed Archive

"Asian Mask?": cropped to image margins: (19.6 x 14.4 cm | 27.0 x 19.6 cm) Japanese tissue gravure: 1900-1920: from: PhotoSeed Archive

However, on close inspection, it might actually appear to be some kind of Asian mask, dressed in what appear to be elaborate silk garments. But these are only guesses. This very fine tissue gravure printed on a thin sheet of Japan laid paper was purchased for this archive from a dealer based in Warwickshire, England in the Fall of 2012. It was purchased at the same time by a lovely pictorialist study that I’ve titled Agnes, which can be seen here.

Does anyone have clues as to the actual subject matter and or author responsible for this mysterious photograph?

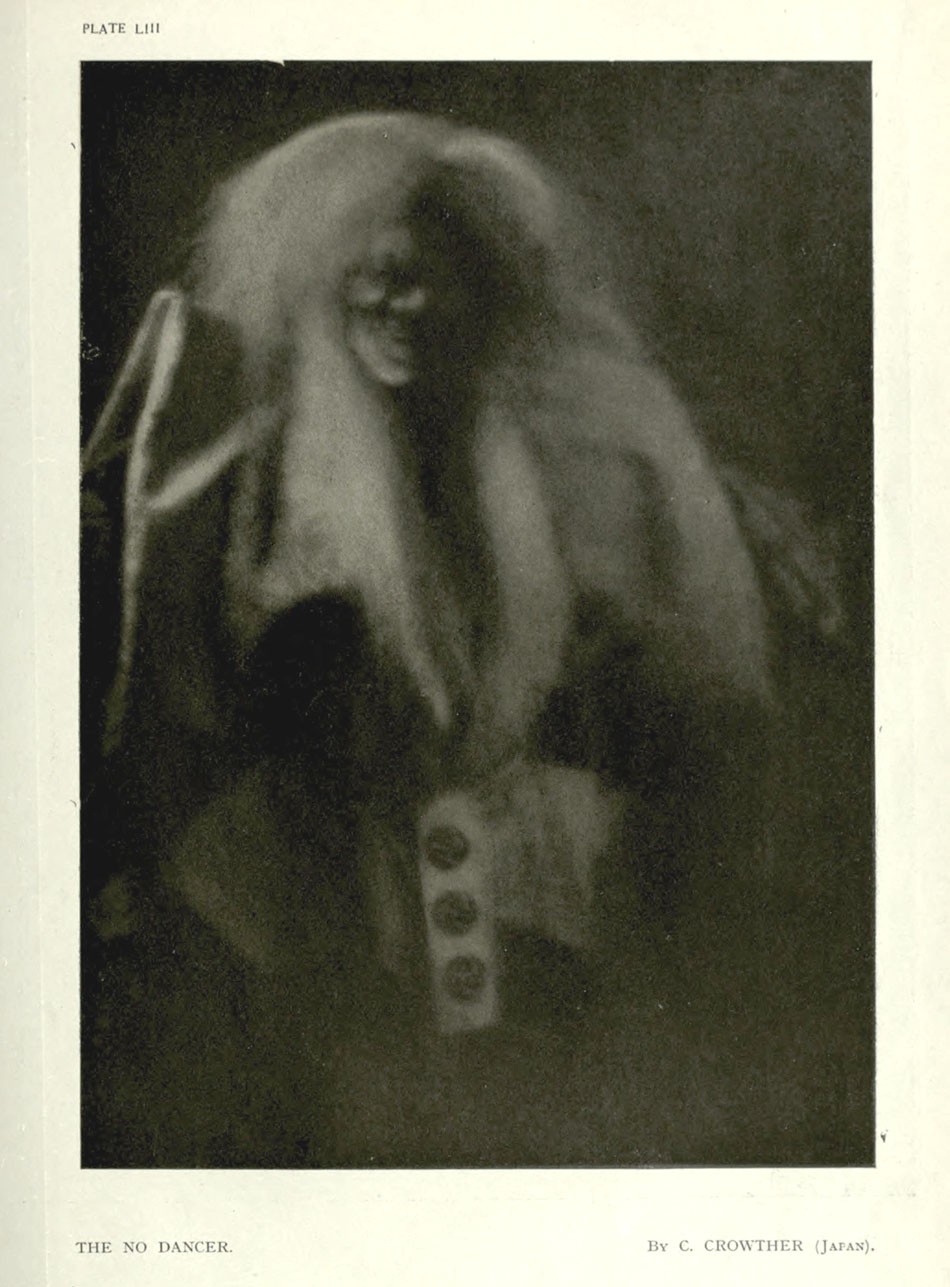

Solved! January, 2020. This portrait shows a Japanese Noh dancer. The variant below was published in Photograms of the Year 1918: The Annual Review of the World’s Pictorial Photographic Work. Please see this link for additional details on the photographer.

"The No Dancer”, Plate LIII: C. Pollard Crowther- 1859-1941: English. Crowther was living and working in Kobe, Japan when this full-page halftone was published in the photographic annual "Photograms of the Year 1918: The Annual Review of the World's Pictorial Photographic Work"- Edited by F.J. Mortimer, F.R.P.S: London: Iliffe & Sons, Limited. From: HathiTrust digital Library

"The No Dancer”, Plate LIII: C. Pollard Crowther- 1859-1941: English. Crowther was living and working in Kobe, Japan when this full-page halftone was published in the photographic annual "Photograms of the Year 1918: The Annual Review of the World's Pictorial Photographic Work"- Edited by F.J. Mortimer, F.R.P.S: London: Iliffe & Sons, Limited. From: HathiTrust digital Library

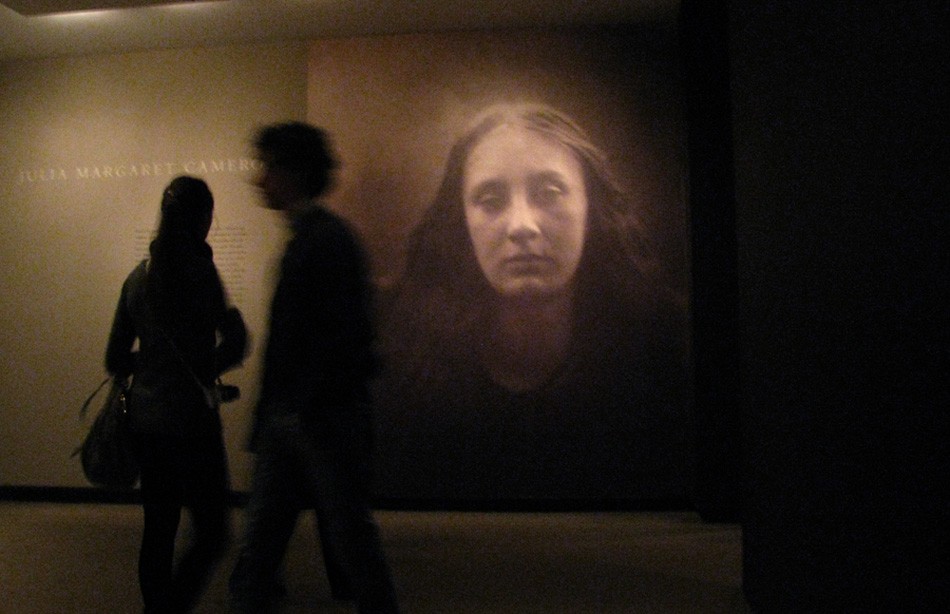

Modernism: meet Pictorialism

Posted March 2014 in Composition, History of Photography, Significant Photographs

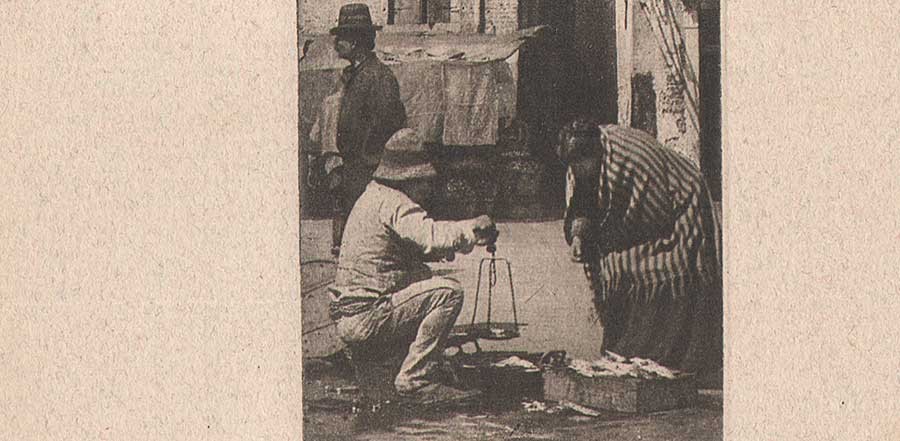

When evaluating the chiaroscuro masterpiece Campo San Margherita by James Craig Annan, a striking vertical composition taken in 1894 during his visit to the Campo San Margherita piazza in Venice-an outdoor market and tourist destination still popular today- the idea of Modernism, a decidedly 20th Century school as applied to the photographic arts, should be taken seriously considering the intent and evidence posed by this finished work.

Detail: "Campo San Margherita": vintage hand-pulled photogravure by James Craig Annan published in Bulletin de l'Association Belge de Photographie: June, 1897: image: 15.0 x 5.1 cm: laid paper support: 22.6 x 15.0 cm: from PhotoSeed Archive

Detail: "Campo San Margherita": vintage hand-pulled photogravure by James Craig Annan published in Bulletin de l'Association Belge de Photographie: June, 1897: image: 15.0 x 5.1 cm: laid paper support: 22.6 x 15.0 cm: from PhotoSeed Archive

Documentary, cubist in form and radically pictorial for its time, this slice of life study showing the interaction of a market vendor and customer can be dissected for compositional posterity with the intent a post-mortem of sorts by this reviewer is reason enough when re-considering the historical record of early photographic aesthetics.